Piercing the Corporate Veil in Defense: Applying the Disregard Doctrine in Japanese Third-Party Objection Suits

The principle of separate corporate personality is a cornerstone of company law, shielding shareholders and affiliated entities from the liabilities of a corporation. However, this shield is not absolute. Under the "doctrine of disregard of corporate personality" (法人格否認の法理 - hōjinkaku hinin no hōri), often referred to as "piercing the corporate veil," courts can look beyond the corporate facade to hold otherwise separate entities or individuals accountable, typically in cases of fraud or abuse of the corporate form to evade obligations.

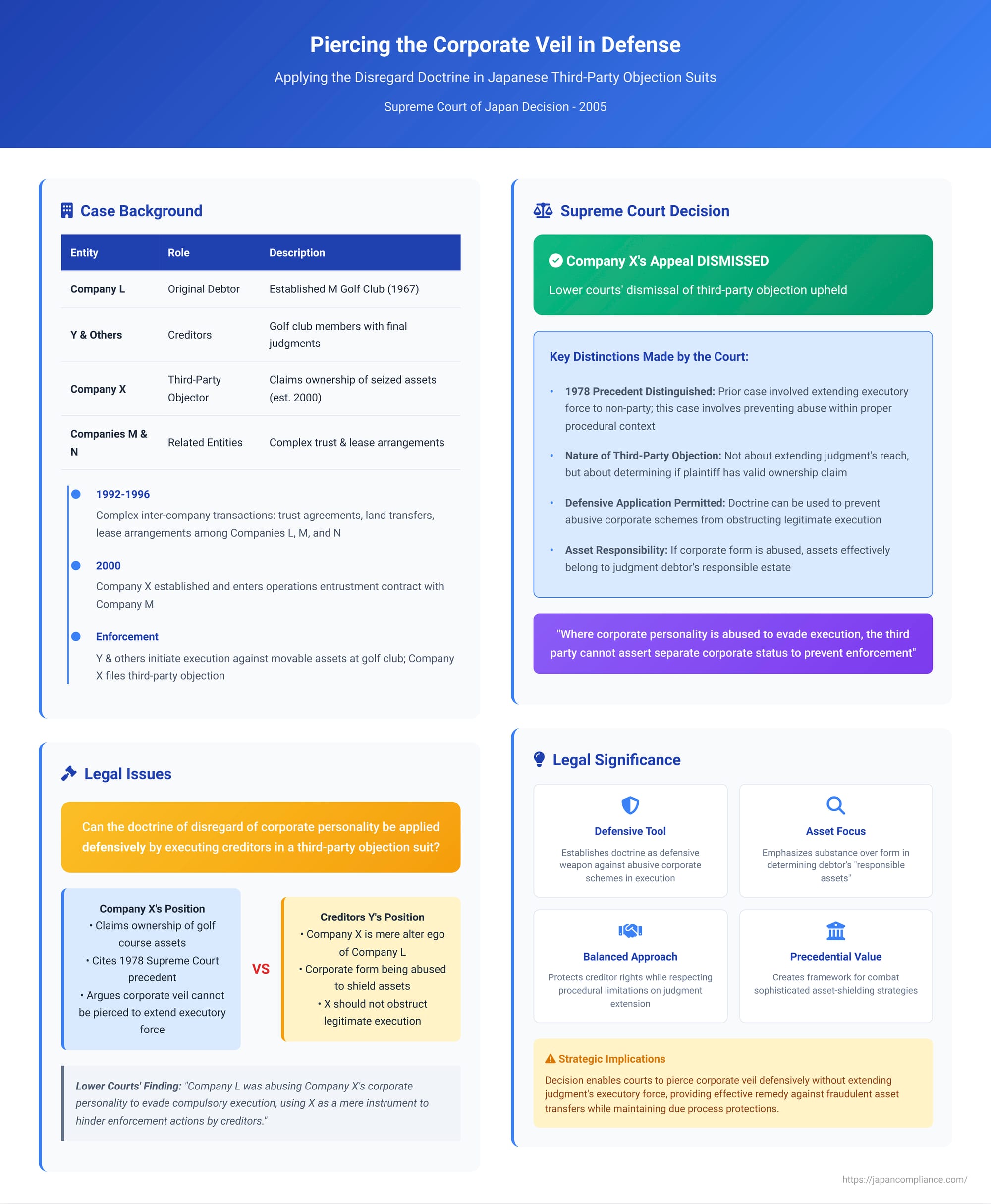

A critical procedural question arises when a creditor tries to enforce a judgment against a debtor company (Company L), and a seemingly separate company (Company X) claims ownership of the assets being seized. If Company X is, in reality, an alter ego or a tool being used by Company L to wrongfully shield assets, can the creditor invoke the disregard of corporate personality doctrine within Company X's "third-party objection suit" (第三者異議の訴え - daisansha igi no uttae) to defeat X's objection? This issue is complicated by established Japanese Supreme Court precedents that generally prohibit the use of this doctrine to directly extend the executory force of a judgment obtained against one company to another non-party company without a new lawsuit. A 2005 Supreme Court decision provided a crucial clarification on this nuanced application.

Background of the Dispute

The case revolved around "M Golf Club," established and initially operated by Company L (founded in 1967). Company L had a deposit-based membership system for the golf club. Several club members, Y and others (the defendants/judgment creditors), had sued Company L for the refund of their membership deposits after the designated holding period expired and they resigned from the club. They obtained final and binding money judgments against Company L.

To enforce these judgments, Y and others initiated compulsory execution against movable assets (such as lawnmowers and cash) located and used at the M Golf Club.

However, a company named X (the plaintiff/third-party objector) stepped in, claiming that these seized assets were either owned by X or were in X's possession under an operations entrustment contract. X filed a third-party objection suit to prevent the execution by Y against these assets.

The corporate structure and history involving the golf course were complex:

- Related Companies: Besides Company L, there were two other closely related companies involved in the golf course's development and management: Company M (established in 1989, originally named N Inc.) and Company N (established in May 1992, originally named M Golf Club Inc.). In August 1992, these two companies swapped their trade names. Companies L, M, and N had virtually identical officer compositions, and Company M and N shared the same head office location.

- Inter-Company Transactions:

- In May 1992, just before the golf course opened, a trust agreement was executed. Company L was the settlor, the (then-to-be-established) Company N was the trustee, and Company M was the beneficiary. The purpose of the trust was stated as "management and disposal" of assets.

- Shortly thereafter, a significant majority share (36/38) of Company L's interest in the land on which M Golf Club was built was transferred to Company N, with "trust" cited as the cause for registration. This occurred just two days before the golf course officially opened.

- In December 1996, Company N (as trustee/landholder) entered into a short-term (3-year) lease agreement with Company M for the ancillary buildings of the golf course.

- Club Bylaws Unchanged: Throughout these inter-company transactions, the M Golf Club's bylaws continued to state that Company L owned, managed, and operated the golf course facilities, and that membership application fees and deposits were to be paid to Company L.

- Plaintiff Company X: Company X was established much later, in February 2000, with the stated purpose of managing and operating golf courses. Its original name was M Co., Ltd., changed to X in 2002. The officer composition of Company X was different from that of Companies L, M, and N.

- Operations Entrustment: In March 2000, shortly after its incorporation, Company X (which had no prior track record in golf course operation) entered into a contract with Company M, whereby Company M entrusted the operational duties of M Golf Club to Company X. This agreement included the transfer of Company M's existing employees to Company X.

- Physical Presence: While Company X had a nameplate on the 3rd floor of its registered head office building, a notice on the door directed visitors to "please go to the 4th floor for assistance." The 4th floor housed the offices of Company L.

The lower courts (both the court of first instance and the High Court) dismissed Company X's third-party objection suit. Their reasoning was that:

- The series of contracts among Companies L, M, and N (the trust agreement, land transfer, and building lease) were likely concluded with the intent to obstruct Company L's creditors from levying execution.

- Company L was found to be in a dominant position, able to use Company X as a mere instrument at its will. Critical decisions regarding the golf course's operations, such as fees, were still effectively made according to Company L's intentions.

- Company L, anticipating numerous lawsuits from club members seeking deposit refunds and subsequent enforcement actions, utilized Company X's corporate form for the unlawful and improper purpose of hindering such compulsory executions.

- Therefore, the courts concluded that Company L was abusing Company X's corporate personality. In relation to the creditors Y, Company X's separate legal personality should be disregarded. Consequently, X's claim to prevent execution was denied.

Company X appealed to the Supreme Court. X argued that the lower courts' decisions violated established Supreme Court precedents, particularly a 1978 decision (Showa 53.9.14) which held that the doctrine of disregard of corporate personality could not be used to extend the executory force of a judgment to a company not named as a party in that judgment.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court of Japan dismissed Company X's appeal, upholding the lower courts' dismissal of X's third-party objection suit. The Court's reasoning carefully distinguished this case from earlier precedents concerning the direct extension of a judgment's executory force:

- Reaffirmation of Limits on Extending Executory Force (Prior Precedents):

The Court began by reaffirming its consistent line of prior rulings (citing key decisions from 1969, 1973, and particularly the 1978 judgment relied upon by X). These precedents established that if one company (e.g., Company L) abuses the corporate form of another company (e.g., Company X) to evade its own debts, while the creditor (Y) may be able to assert a claim against either company substantively under the doctrine of disregard of corporate personality, the res judicata (binding effect of a judgment) and the executory force (enforceability) of a judgment obtained solely against Company L cannot be extended to Company X (which was not a party to the original judgment) simply by applying the disregard of corporate personality doctrine. This means a creditor cannot, for instance, take a judgment against Company L and then directly obtain a writ of execution naming Company X as the debtor based on piercing the veil, without a new adjudication involving Company X. - The Distinct Nature of a Third-Party Objection Suit:

The Supreme Court then crucially distinguished the nature and purpose of a third-party objection suit (filed by X in this instance) from the scenarios addressed in the precedents cited by X. The Court explained that a third-party objection suit is not a proceeding where the plaintiff (the third party, X) argues that the executory force of the original title of obligation (the judgment against L) does not extend to them.

Instead, a third-party objection suit is filed when, in the course of a compulsory execution that has been lawfully initiated against a judgment debtor (L), the plaintiff third party (X) asserts that they possess ownership of the targeted property or other rights that would prevent the transfer or delivery of that property. In essence, the third party argues that they should not have to tolerate their property being seized and sold to satisfy the judgment debtor's obligations. - Applicability of the Disregard Doctrine Within a Third-Party Objection Suit:

Given this understanding of a third-party objection suit, the Supreme Court found no reason to exclude the application of the doctrine of disregard of corporate personality as a defense by the executing creditor (Y) against the third-party plaintiff (X).

The Court reasoned that if the plaintiff third party's (X's) corporate personality is being abused for the purpose of evading compulsory execution against the actual judgment debtor (L), then the plaintiff (X) should not be permitted to assert its separate corporate status from the judgment debtor (L) as a basis for demanding that the compulsory execution be disallowed. - Application to the Present Case:

The lower courts had found as a matter of fact that Company L was abusing Company X's corporate personality to evade compulsory execution against itself. Accepting these factual findings, the Supreme Court concluded that the doctrine of disregard of corporate personality was applicable. Therefore, in this third-party objection suit initiated by Company X, Company X could not be permitted to assert its separate corporate identity from Company L as a ground to prevent the enforcement actions (the seizure of movables at the golf course) by Y and others.

The Supreme Court explicitly stated that its 1978 decision, which X had relied upon, dealt with a different factual scenario (an action for the grant of a writ of execution against an alleged alter ego) and was therefore not pertinent to the current case. This case did not involve extending the executory force of the judgment against L to X (e.g., by naming X in a new writ). Rather, it involved determining whether X could legitimately claim its own assets were being seized when, due to the abuse of its corporate form by L, those assets were effectively L's for the purpose of satisfying L's creditors.

Significance and Analysis of the Decision

This 2005 Supreme Court judgment is highly significant for its nuanced application of the doctrine of disregard of corporate personality within the specific procedural context of a third-party objection suit. It carves out a way for creditors to combat abusive corporate schemes without directly contravening the established principle against simply extending a judgment's executory force to non-parties.

- Strategic Use of the Disregard Doctrine: The decision clarifies that while the doctrine cannot be used by a creditor to offensively obtain a writ of execution against an alter ego company based on a judgment against the original debtor (as per the 1978 precedent), it can be used defensively by the creditor when that alter ego company (as a third-party plaintiff) tries to shield assets from execution.

- Focus on "Responsible Assets": The PDF commentary supports this outcome, noting that the majority academic view aligns with the idea that a third-party objection suit primarily concerns whether the seized property constitutes part of the judgment debtor's "responsible assets" (責任財産 - sekinin zaisan)—assets legitimately available to satisfy the debtor's obligations. The application of the disregard doctrine then becomes a question of substantive law: can the third-party plaintiff (X) validly assert its separate legal personality to claim the assets are not part of the judgment debtor's (L's) responsible assets? If X's corporate form is an abusive sham controlled by L, the answer is no. This approach neatly sidesteps the procedural difficulties and due process concerns associated with directly extending the executory force of a judgment to a non-party. The execution remains formally against L, but X is prevented from obstructing it due to the abuse.

- Distinction from Extending Executory Force is Key: The Supreme Court was careful to emphasize that this case did not involve extending the original judgment's executory force to Company X. The execution was initiated based on judgments against Company L, targeting assets effectively under L's control or beneficial ownership, despite X's nominal claim. The disregard doctrine was applied to negate X's attempt to use its separate legal status as a shield. This is different from a creditor trying to get a new writ naming X as the debtor based on a judgment against L.

- Practical Implications for Different Types of Assets: The PDF commentary briefly touches upon whether the fact that this case involved movable assets (where possession is a primary, albeit rebuttable, indicator of ownership for execution purposes) was a critical factor. If the assets had been real estate registered in X's name, the analysis might become more complex if the execution was based solely on L's debt, because execution against real property heavily relies on the land registry. However, the underlying principle of preventing abuse of the corporate form should arguably still apply. The factual findings of control and abuse by L over X would remain paramount. The complex inter-company transactions involving the golf course land itself (transferring most of L's interest to Company N via a trust) highlighted the sophisticated asset-shielding strategies that can be employed, making effective creditor remedies crucial.

- Continuing Debate on Broader Procedural Applications: While this decision provides a valuable tool for creditors in third-party objection suits, the PDF commentary notes that the broader debate about other procedural applications of the disregard doctrine (such as extending res judicata or executory force in "shell company" scenarios) continues in academic circles. However, the trend seems to be that such extensions are viewed cautiously due to due process concerns for the non-party, the need for full factual inquiries not suited to summary procedures, and the adequacy of alternative remedies like new substantive lawsuits against the alter ego or applying general principles like good faith in specific procedural contexts. This 2005 ruling fits well within a framework that uses the disregard doctrine to address the substantive merits of asset ownership in an appropriate procedural context, rather than by altering the direct reach of a prior judgment.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2005 decision provides an important clarification on the application of the doctrine of disregard of corporate personality in Japanese civil execution proceedings. It confirms that while the doctrine cannot be used to directly extend the executory force of a judgment against one company to an affiliated non-party company without a new adjudication, it can be legitimately invoked by a judgment creditor as a defense when the non-party company (whose corporate form is being abused by the judgment debtor) files a third-party objection suit to shield assets from execution. This allows courts to look through an abusive corporate structure to prevent a judgment debtor from fraudulently evading its obligations, thereby ensuring that the assets effectively controlled by or belonging to the debtor remain available to satisfy creditors, while still respecting the general principles governing the scope of judgment enforcement.