Phantom Goods & Borrowed Names: Japanese Courts Tackle Sham Credit and Identity Misuse in Loan Agreements

Judgment Dates: September 28, 2000 (Tokyo High Court) and July 11, 2002 (Supreme Court)

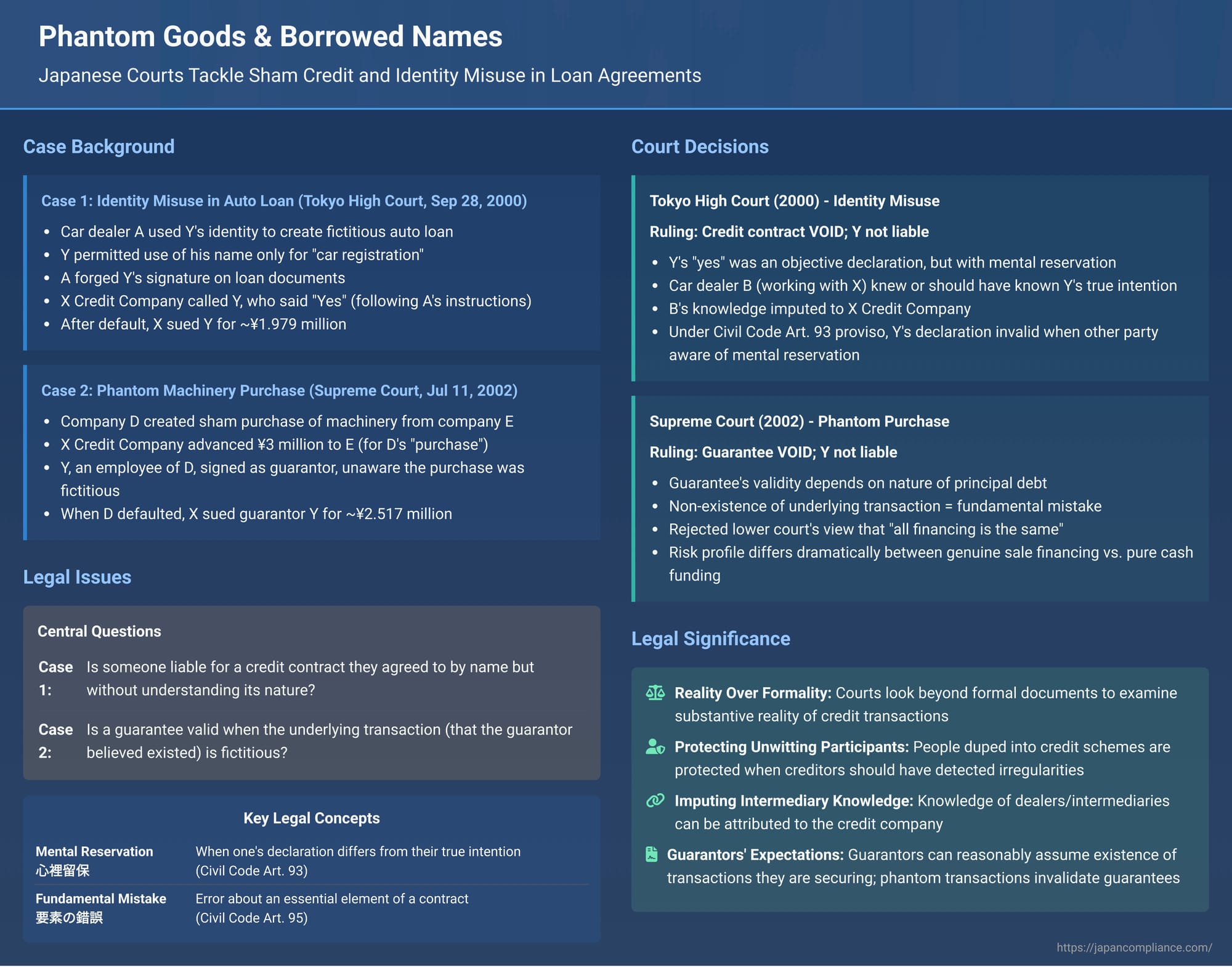

The world of credit transactions, while essential for commerce, can unfortunately be exploited through various fraudulent schemes. Two significant Japanese court decisions, one from the Tokyo High Court and another from the Supreme Court, shed light on the legal ramifications when such schemes unravel, particularly focusing on "sham credit agreements" (where no actual underlying sale of goods occurs) and the misuse of an individual's name to secure loans. These cases illustrate how Japanese courts scrutinize the realities behind contractual appearances to protect unwitting parties.

Case Study ①: The Auto Loan That Wasn't – Identity Misuse and Lender Liability

(Tokyo High Court, Judgment of September 28, 2000; Heisei 12 (Ne) No. 1143)

This case involved a complex scheme where an individual's identity was misused to obtain an auto loan, and the court had to determine the liability of the nominal debtor who was duped into participation.

- The Deception:

A, a car dealer, devised a plan to secure funds by creating fictitious auto loan credit contracts using the name of Y (the defendant). A approached Y with a deceptive story, requesting permission to use Y's name for car registration purposes only. A claimed this was to facilitate the resale of used cars he had acquired, arguing that using a dealer's name often led to buyers demanding discounts. A assured Y that if any loan company called regarding the car's name, Y should simply respond affirmatively ("yes, yes, please proceed"). Trusting A, Y agreed to allow his name to be used for vehicle registration, believing this was the full extent of his involvement.Unbeknownst to Y, A then approached B, another car dealer who also acted as an agent for X Credit Company's auto loan services. A told B that Y wished to purchase a car and utilize X's loan services. B agreed to process the loan application. A proceeded to forge Y's signature on X Credit Company's contract documents, creating a set of agreements in Y's name. These included: (1) a purported sales contract for a vehicle ("the Vehicle") between dealer B (as seller) and Y (as buyer); (2) a loan agreement between Y and C Insurance Company (as the direct lender) for the vehicle's purchase price plus guarantee commission fees, totaling approximately ¥2.576 million; and (3) a guarantee commission contract between Y and X Credit Company, whereby Y requested X to guarantee Y's loan obligation to C Insurance Company, and X agreed. A also illicitly opened a bank account in Y's name, listed this account on the loan documents for repayments, and affixed a commonly available (non-registered) seal bearing Y's name to the documents. These forged documents were submitted by A to dealer B, who then forwarded them to X Credit Company.Upon receiving the application, a representative from X Credit Company telephoned Y at his workplace on August 20, 1996, to confirm his intention to enter into the credit agreement. Y, following A's prior instructions and still believing this was merely related to using his name for car registration, responded with "Yoroshiku onegaishimasu" (a common affirmative phrase meaning "Please proceed" or "Okay, I understand").Later, X Credit Company requested Y's official certificate of registered seal. A obtained this from Y under the false pretense that it was needed for the vehicle name registration. A then procured a seal with an imprint similar to Y's registered seal, re-stamped the contract documents with this new seal, and submitted these along with Y's genuine seal certificate to dealer B.Based on these manipulated procedures, the credit agreement was deemed formally concluded on September 10, 1996. On September 17, X Credit Company (as guarantor having facilitated the loan from C Insurance) ensured the loan amount corresponding to the Vehicle's purchase price was disbursed to dealer B. However, B had already paid the full sum to A on September 13. A used all these funds to settle his own debts. Y remained entirely unaware of these financial transactions, had never visited B's dealership, had not negotiated any purchase, had never seen the Vehicle, and had not received any money from A.A initially made some installment payments on the loan from the fraudulently opened bank account in Y's name but began defaulting around July 1997. This led X Credit Company (which had presumably paid out C Insurance Company under its guarantee) to send demand letters to Y. It was only then, upon confronting A, that Y discovered the full extent of the sham credit contract created in his name. X Credit Company subsequently sued Y for reimbursement of the approximately ¥1.979 million it had paid out. Y denied any liability, asserting his name had been misused by A. - The Tokyo High Court's Ruling:

The Tokyo High Court dismissed X Credit Company's claim against Y. The court's reasoning centered on the concept of "mental reservation" (心裡留保 - shinri ryūho) under Article 93 of the Civil Code.- Y's Phone Response as an Objective Declaration: The Court acknowledged that Y's affirmative response ("Yoroshiku onegaishimasu") during the telephone confirmation call with X Credit Company's representative objectively constituted a declaration of intent to enter into the credit agreement.

- Y's Lack of True Intent (Mental Reservation): However, Y's true intention was merely to permit the use of his name for vehicle registration; he had no genuine intention to become the debtor under a credit agreement. This discrepancy between his outward declaration and his inner intent constituted a mental reservation.

- Applicability of Civil Code Article 93 Proviso: Article 93, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code states that a declaration of intent is not invalidated even if the declarant did not actually intend what was expressed, unless the other party knew, or should have known, of the declarant's true intention (the proviso). If the other party (X Credit Company) was aware or should have been aware that Y did not truly intend to be bound by the loan, Y's declaration would be void.

- Imputing Dealer B's Knowledge to X Credit Company: This was a crucial step. The Court found that dealer B, who processed the application and interacted directly with A, knew or, through exercising reasonable care, should have known that A was engaged in a fraudulent scheme and that Y had no genuine intention of undertaking the loan obligations. Although B was not X Credit Company's formal agent for concluding the contract, B handled essential parts of the credit application process. The High Court reasoned that given the practical realities of such three-party credit transactions (seller-consumer-credit company), where the seller/dealer often acts as the primary interface for the consumer and prepares/submits the application documents, the dealer (B) was in a position substantially similar to that of an agent for the credit company (X) in this context. Therefore, B's knowledge (or constructive knowledge) of Y's lack of true intent was imputed to X Credit Company.

- Conclusion: Since X Credit Company (through the imputed knowledge of dealer B) knew or should have known that Y's affirmative response was not backed by a genuine intent to become the debtor, Y was entitled to assert the invalidity of his declaration of intent under the proviso of Civil Code Article 93. The credit agreement was therefore deemed void as far as Y was concerned, and X Credit Company could not enforce it against him.

Case Study ②: Guaranteeing a Phantom Purchase – Sham Credit and a Guarantor's Fundamental Mistake

(Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, Judgment of July 11, 2002; Heisei 11 (Ju) No. 602)

This case dealt with a "sham credit" (空クレジット - kara kurejitto) arrangement, where a credit agreement was created based on a fictitious sale of goods, and the liability of a guarantor who unknowingly backed this sham transaction.

- The Sham Transaction:

The representative of company D planned to raise operating funds through a sham credit deal. Although no actual sale of "the Machinery" was to occur, D purported to purchase it from company E. On December 6, 1995, X Credit Company entered into a "payment advance agreement" (立替払契約 - tatekaebarai keiyaku) with D. Under this agreement:X Credit Company advanced the ¥3 million to E on January 5, 1996. D subsequently defaulted on its first installment payment due by February 27, 1996, triggering the acceleration clause.- X Credit Company would pay E ¥3 million, purportedly for "the Machinery" D was buying from E.

- D would repay X Credit Company a total of ¥3,780,333 (principal plus fees) in installments.

- If D missed even one payment, it would lose the benefit of time (acceleration clause).

D and E had secretly agreed that E would receive the ¥3 million from X Credit Company and then transfer the net amount (after deducting fees) to D.

On the same day, Y, an employee of D, signed a joint and several guarantee agreement (本件保証契約 - honken hoshō keiyaku) with X Credit Company for D's obligations under the payment advance agreement. Both X Credit Company and Y (the guarantor) were unaware at the time that the underlying sale of "the Machinery" from E to D was fictitious; they believed it to be a genuine transaction.

- The Guarantor's Defense: X Credit Company sued Y, the guarantor, for the outstanding balance of approximately ¥2.517 million. Y defended by arguing that the principal payment advance contract between X and D was a sham credit deal (no actual delivery or sale of goods from E to D), and that Y was unaware of this when he signed the guarantee. Y asserted that his guarantee was therefore void due to a "fundamental mistake" (要素の錯誤 - yōso no sakugo) concerning an essential element of the transaction, as per former Article 95 of the Civil Code. (Note: The Civil Code provisions on mistake were revised in 2017, but this case was decided under the former law).

- Lower Courts' Rulings: Both the Tokyo District Court and the Tokyo High Court rejected Y's mistake defense and ruled in favor of X Credit Company. They reasoned that the economic substance of both genuine credit (linked to a real sale) and sham credit is essentially financing. Therefore, they held that the existence or non-existence of an actual underlying sale of the machinery was not an essential element of the guarantee contract from the guarantor's perspective, and Y's misunderstanding was merely a mistake in motive which had not been made a term of the contract. Y appealed to the Supreme Court.

- The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling on Guarantor's Mistake:

The Supreme Court reversed the lower courts' decisions, found in favor of the guarantor Y, and dismissed X Credit Company's claim.- Nature of the Principal Debt is Crucial for a Guarantee: The Court emphasized that a guarantee contract is an agreement to secure a specific principal debt. Therefore, the nature and characteristics of that principal debt are inherently important components of the guarantee contract itself.

- Underlying Sale as a Premise for Sales-Linked Credit: When the principal debt arises from a payment advance agreement (like an installment credit plan) where a credit company pays a seller on behalf of a buyer for purchased goods, the existence of a genuine sales contract for those goods is a fundamental premise of the payment advance agreement. Consequently, the existence or non-existence of this underlying sales contract is, in principle, an important and essential element of any guarantee contract that secures such a payment advance obligation.

- Application to the Sham Credit Scenario: In this case:

- The payment advance agreement between X Credit Company and D, while structured as financing for D's purchase of "the Machinery" from E, was in fact a sham credit because no actual sale of machinery existed.

- Y, the guarantor, was unaware of this fictitious underlying sale when he signed the guarantee agreement.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that Y's declaration of intent to guarantee D's debt was predicated on a fundamental mistake concerning an essential element of the legal act—namely, a mistake about the true nature of the principal debt he was undertaking to guarantee. He believed he was guaranteeing a debt arising from a legitimate commercial transaction involving tangible assets, not a debt arising from a pure financing scheme disguised as a sale.

- Economic Substance vs. Legal Nature and Risk for Guarantors: The Supreme Court acknowledged the lower courts' point that the economic function of both genuine and sham credit might appear similar (providing finance). However, it countered that this does not equate to them being legally or practically the same from a guarantor's perspective:

- There is a practical and significant difference in the creditworthiness and risk profile of a debtor in a genuine sales credit transaction (where actual goods exist, potentially offering some, even if diminishing, security or at least indicating a legitimate business purpose for the debt) compared to a debtor in a sham credit transaction designed merely to raise funds illicitly.

- A guarantor's risk exposure is substantially different in these two scenarios. Guaranteeing a debt for a phantom asset carries a different, often higher, risk than guaranteeing a debt for an actual asset.

- Especially when, as in this case, the payment advance agreement and the guarantee contract were documented on the same set of forms explicitly showing a seller (E), specific goods ("the Machinery"), and a purchase price, the guarantor (Y) would naturally and reasonably assume it was a regular, legitimate transaction involving a real sale. This assumption forms the basis of their intention to provide the guarantee.

- Conclusion: Y's guarantee was void due to a fundamental mistake as to an essential element of the contract. X Credit Company could not enforce the guarantee against Y.

Key Principles and Takeaways from These Cases

These two judgments, while arising from different factual scenarios (identity misuse vs. sham underlying sale), offer important insights into how Japanese courts approach deceptions in credit transactions:

- Scrutiny Beyond Formal Declarations (Case ① - Mental Reservation): While a person's objective declaration of intent (like Y's "yes" on the phone) is generally binding, courts may look behind it if there is clear evidence of a mental reservation (a disconnect between the declared intent and true intent), and the other party to the contract (or their effective intermediary, like the dealer in Case ①) knew or should have known of this true state of mind. This protects individuals who are manipulated into making declarations without genuine corresponding intent, provided the counterparty's awareness can be established (directly or by imputation).

- The Role of Intermediaries (Case ① - Imputed Knowledge): In three-party credit transactions (consumer-dealer-finance company), the actions and knowledge of the intermediary dealer who facilitates the credit application can be critically important. If the dealer is aware of fraud or the consumer's lack of true contractual intent, this knowledge may be imputed to the finance company, potentially voiding the contract for the consumer.

- Protecting Unknowing Guarantors from Sham Debts (Case ② - Fundamental Mistake): A guarantor's understanding of the fundamental nature of the principal debt they are guaranteeing is paramount. If a guarantor is led to believe they are backing a debt arising from a genuine sale of assets, when in fact the underlying transaction is a sham designed merely to channel funds, their guarantee may be void due to a fundamental mistake as to an essential element of their undertaking. The existence (or non-existence) of a real underlying commercial transaction significantly alters the risk profile and the basis of the guarantor's decision.

- "Sham Credit" as a Distinct Problem: The Supreme Court in Case ② explicitly recognized the problematic nature of "sham credit" (空クレジット) transactions, where the facade of a sale and purchase is used to disguise what is essentially a pure (and often riskier or less transparent) financing arrangement.

While later legislative developments, such as amendments to the Installment Sales Act and the Consumer Contract Act, have introduced more specific protections for consumers in various credit-related situations, these cases demonstrate how general principles of the Civil Code—such as those concerning mental reservation and fundamental mistake—have been applied by Japanese courts to address fraudulent and deceptive practices in the realm of credit and guarantees, aiming to protect parties who were unwittingly drawn into illicit or misrepresented transactions.