Personality vs. Pathology: How Japan's Supreme Court Dissects the Criminal Mind

Decision Date: December 8, 2009

Few questions in criminal law are more profound or difficult than determining a defendant's mental capacity at the time of their offense. The line between a culpable criminal act and a tragic manifestation of severe mental illness is often blurry, forcing the legal system to navigate the complex intersection of law and psychiatry. The central challenge is defining the proper roles: what is the duty of the medical expert, and what is the ultimate responsibility of the judge?

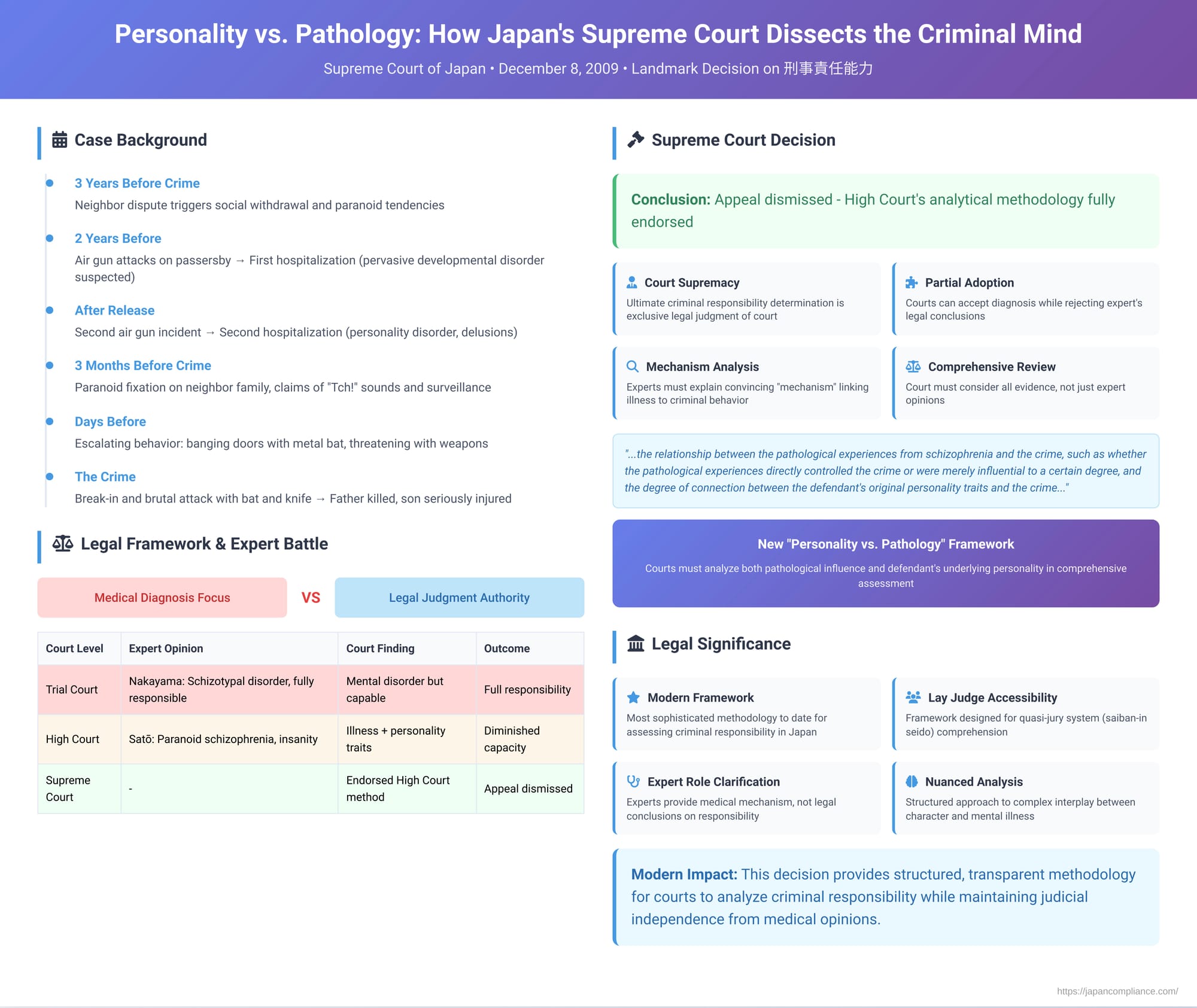

On December 8, 2009, the Supreme Court of Japan issued a landmark decision in a case involving a brutal murder committed by a man with a long history of mental health issues. The ruling provides the most sophisticated judicial methodology to date for assessing criminal responsibility. It reaffirms the court's supremacy in making the final legal judgment while simultaneously providing a new analytical framework—a balancing of the defendant's underlying "personality" against their "pathology"—to guide that judgment in a more structured and transparent way.

The Factual Background: A Descent into Paranoia and Violence

The case involved a defendant with a deeply troubled history. Three years before the crime, a dispute with a downstairs neighbor sent him into a spiral of social withdrawal. Two years prior, he began shooting an air gun from his window at random passersby. This led to his first involuntary psychiatric hospitalization, where he was diagnosed with a suspected pervasive developmental disorder. After his release, he was arrested again for shooting a neighbor with the air gun, leading to a second hospitalization with diagnoses including personality disorder and suspected "delusions."

Following his second release, the defendant went to live with his grandmother. For a time he was stable, but his condition deteriorated again about three months before the crime. He developed a paranoid fixation on the family living next door to his grandmother, claiming their son was making "Tch!" sounds at him and that the family was spying on him with listening devices. His paranoia escalated: he papered over his windows, hired a professional to sweep his home for bugs, and trespassed onto the victim's property, for which he was reprimanded.

In the days leading up to the murder, his behavior became more menacing. He banged on the victim's front door with a metal bat. Hours before the attack, he confronted the victim while brandishing the bat. Finally, in the early hours of the morning, after driving around with a friend, the defendant took the metal bat and a survival knife, broke into the victim's home through an unlocked window, and brutally attacked the family. He killed the father and seriously injured one of the sons.

After the crime, he fled but was soon confronted by police. He threatened them with another knife, shouting "I've stabbed someone. I don't care what happens to me now," and "Shoot me with your pistol. Kill me."

A Battle of Experts Through the Courts

The defendant's criminal responsibility was the central issue at every stage of the legal proceedings, leading to a classic "battle of the experts."

- The Trial Court: The first-instance court relied on a psychiatric evaluation (the "Nakayama evaluation") conducted during the investigation. This report diagnosed the defendant with a "schizotypal disorder" but suggested he was fully responsible for his actions. The trial court, however, chose not to rely on this specific diagnosis, instead finding that while the defendant had a "mental disorder in the peripheral domain of schizophrenia," he was still fully capable of understanding the wrongfulness of his actions. It based this on the planned nature of the crime and his clear memory of the events, finding him to have full criminal responsibility.

- The High Court: The appellate court commissioned a new, more thorough psychiatric evaluation (the "Satō evaluation"). This second expert concluded that the defendant was suffering from paranoid schizophrenia at the time of the crime and that the attack was a direct "acting out" of his pathological experiences (delusions and hallucinations). The Satō evaluation concluded that the defendant was legally insane (shinshin sōshitsu) and lacked criminal responsibility.The High Court then made a crucial analytical move. It accepted the diagnosis of schizophrenia from the Satō evaluation but rejected its conclusion of insanity. The court held that a diagnosis, even one that links the crime to a pathological experience, "does not immediately mean that the defendant was in a state of insanity." The court declared that it must also examine the relationship between the pathology and the crime.In its own analysis, the High Court found that the crime was not "entirely divorced from the defendant's original personality." It was a product of both his illness and his underlying personality traits. Therefore, the court rejected the finding of insanity but, acknowledging the powerful influence of his illness, found that his capacity was "markedly diminished." It convicted him on the basis of diminished capacity (shinshin kōjaku).

The Supreme Court's Definitive Ruling: A Method for Judgment

The defendant appealed, arguing that the court should have fully accepted the Satō evaluation's conclusion of insanity. The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal and, in a detailed opinion, fully endorsed the High Court's sophisticated methodology.

Reaffirming Core Principles:

The Court began by restating the foundational principles governing the assessment of criminal responsibility:

- The ultimate determination of responsibility is a legal judgment reserved exclusively for the court.

- The court can choose not to adopt an expert's opinion if there are "rational grounds" to do so, such as problems with the expert's underlying data or reasoning process.

A New and Critical Clarification:

The Court then added a crucial clarification to these principles: a court is free to accept one part of an expert's report (such as the medical diagnosis) while simultaneously rejecting another part (such as the final opinion on legal capacity). A court is not "factually bound" to accept a report in its entirety.

Endorsing the High Court's Method:

The Supreme Court explicitly praised the High Court's analytical process. It found that the High Court was justified in rejecting the Satō evaluation's conclusion of insanity because the report had failed to provide a "sufficiently convincing explanation of the mechanism" by which the defendant's delusions had "directly controlled and caused" the crime. The expert report could not adequately account for the defendant's seemingly rational behavior before and after the attack or the fact that his delusions (e.g., being taunted by telepathy) were not of a nature that would typically lead to such a violent murderous rage.

The "Personality vs. Pathology" Framework:

Most importantly, the Supreme Court formally endorsed the High Court's new analytical framework. It stated that a court should "comprehensively consider" all the evidence by examining:

"...the relationship between the pathological experiences from schizophrenia and the crime, such as whether the pathological experiences directly controlled the crime or were merely influential to a certain degree, and the degree of connection between the defendant's original personality traits and the crime..."

This "personality vs. pathology" analysis was officially integrated into the Court's jurisprudence.

The Modern Framework for Assessing Criminal Responsibility

This 2009 decision is significant because it synthesizes decades of case law into a clear, modern methodology, partly in response to the introduction of Japan's quasi-jury system (saiban-in seido), which involves lay citizens in major criminal trials. The "personality vs. pathology" framework was seen as a more intuitive and accessible way for non-lawyers to approach the abstract concepts of criminal responsibility.

The ruling also clarifies the role of the psychiatric expert in the modern Japanese courtroom. The expert's primary function is not to provide a legal conclusion but to explain the medical "mechanism"—to detail the defendant's illness and symptoms and to provide a convincing account of how those symptoms may have influenced their behavior. An expert report that fails to do so, as the Court found in this case, may be deemed insufficient, allowing the court to make its own determination based on all the other evidence.

Conclusion: A Sophisticated Method for a Complex Question

The Supreme Court's 2009 ruling provides the most detailed and sophisticated judicial methodology to date for assessing criminal responsibility in Japan. It empowers judges to be critical and active consumers of expert evidence, accepting medical diagnoses while independently evaluating their legal consequences. By formally adopting the "personality vs. pathology" framework, the Court has provided a structured way to analyze the complex interplay between an individual's underlying character and the profound influence of mental illness. This landmark decision demands a more rigorous explanation of the "mechanism" linking illness to action, pushing both legal and psychiatric professionals toward a more nuanced, transparent, and legally sound analysis of the criminal mind.