Perfecting Rights to Standing Timber in Japan: The Enduring Requirement of "Meinin Hōhō" (Clear Recognition)

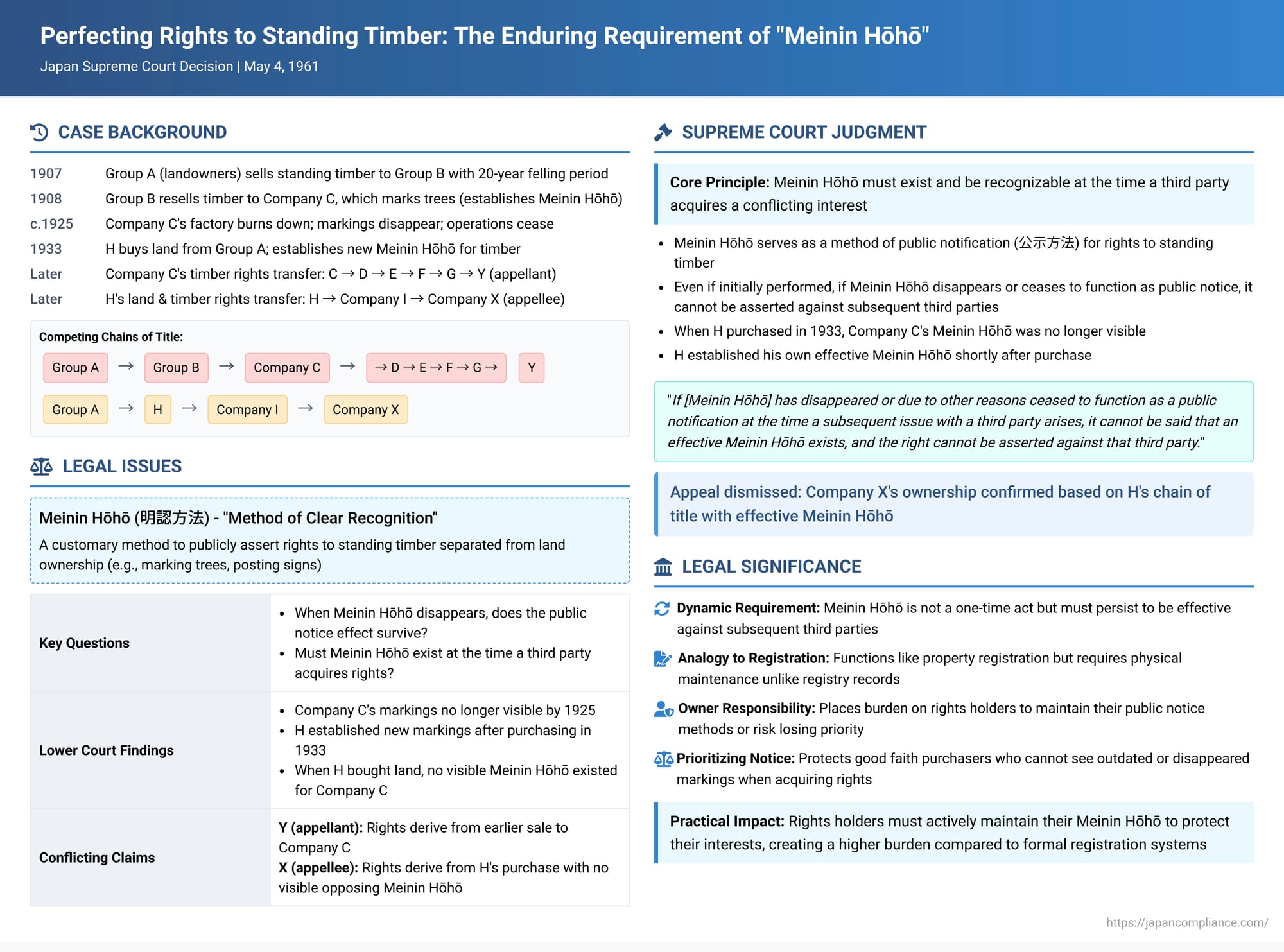

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Judgment of May 4, 1961 (Showa 36) (Case No. 355 (O) of 1957 (Showa 32))

Subject Matter: Claim for Confirmation of Ownership of Standing Timber, etc. (立木所有権確認等請求事件 - Tachiki Shoyūken Kakunin tō Seikyū Jiken)

Introduction

This article examines a 1961 Japanese Supreme Court judgment that addresses the requirements for perfecting ownership of standing timber (立木 - tachiki) that is treated as separate property from the land it stands on, particularly when such timber is not registered under the Standing Trees Act (立木法 - Tachiki Hō). The case focuses on a customary Japanese legal practice known as "Meinin Hōhō" (明認方法), which translates to "method of clear recognition." The Court affirmed the crucial principle that for a Meinin Hōhō to be effective in asserting ownership against a subsequent third party who acquires a conflicting interest, this method of public notification must not only be established at the time of the initial acquisition but must also persist and be recognizable at the time the third party's interest arises.

The dispute involved Company X (appellee/plaintiff), which claimed ownership of standing timber through a chain of title originating from H, who had purchased the land and timber. The opposing party was Y (appellant/defendant), who claimed ownership of the same timber through a different, earlier chain of transactions.

Factual Background

The forest land in question was originally co-owned by Group A. In 1907 (Meiji 40), the standing timber on this land was sold by Group A to Group B, with a stipulated felling period of 20 years. The following year, 1908, Group B resold this timber to Company C (a timber company). After purchasing the timber, Company C established an office and factory on the forest land and began felling operations. As a method of asserting its ownership of the timber (Meinin Hōhō), Company C marked standing trees at various locations by carving or branding its mark, or by nailing boards with its mark onto the trees.

However, around 1925 (Taisho 14), Company C's factory burned down, and its felling operations naturally ceased. By that time, the markings (Meinin Hōhō) previously established by Company C were reportedly no longer visible or had disappeared. Subsequently, Company C transferred the timber rights to D, and the rights were then further transferred through E, F, and G, with G eventually gifting them to Y (the appellant).

Meanwhile, the land itself (the ground of the forest) was sold by the original co-owners, Group A, to H in 1933 (Showa 8). At the time of this sale, Group A believed that because the 20-year felling period granted to the initial timber purchasers (Group B, and by extension Company C) had expired, the rights to the standing timber had reverted to them, the landowners. However, they were not entirely certain, so the sale agreement to H did not explicitly clarify whether the standing timber was included or excluded. Shortly after purchasing the land, H established his own Meinin Hōhō for the standing timber by erecting marking stakes indicating his ownership at key points on the land and by carving similar marks into trees at several locations.

The land (and the timber rights H claimed) was later transferred from H to Company I (a paper company), and then from Company I to Company X (another paper company, the appellee), with each transfer of land ownership being duly registered. Company X then sued Y, seeking confirmation of its ownership of the standing timber and an injunction to prevent Y from entering the land and felling or removing the timber.

Both the first instance court and the appellate court ruled in favor of Company X. The appellate court reasoned that:

(1) The expiration of the original felling period did not automatically cause the ownership of the timber to revert from Company C to Group A.

(2) However, for standing timber not governed by the Standing Trees Act, if not explicitly excluded, it should generally be considered sold along with the land. Therefore, the timber was effectively transferred from Group A to H when H bought the land. This created a "double sale" situation for the timber: first from Group A (via Group B) to Company C, and later from Group A to H.

Crucially, the appellate court held that Meinin Hōhō, as a means of public notification for third parties, must not only be performed at the time of the property right change but must also exist and be effective when a third party acquires a conflicting interest. Y appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, affirming the lower courts' decisions in favor of Company X.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Nature and Requirement of Meinin Hōhō: The Court acknowledged that "Meinin Hōhō" is recognized as a method of public notification (公示方法 - kōji hōhō) for changes in real rights (物権変動 - bukken hendō) concerning standing timber that is not subject to the Standing Trees Act. As such, it serves as an alternative to registration. Therefore, it must be a means by which a third party can easily recognize the ownership and, significantly, it must exist with such effect at the time the third party acquires their interest.

- Consequence of Disappeared Meinin Hōhō: Consequently, even if a Meinin Hōhō was once performed at the time of the right's transfer, if it has disappeared or due to other reasons ceased to function as a public notification at the time a subsequent issue with a third party arises, it cannot be said that an effective Meinin Hōhō exists, and the right cannot be asserted against that third party. The Supreme Court explicitly endorsed the appellate court's view on this point and cited its own prior consistent precedents (Daishin'in, Nov. 10, 1917; Daishin'in, July 22, 1931; Sup. Ct., Mar. 1, 1960).

- Application to the Facts:

- The Court affirmed the factual findings that although Company C had initially implemented Meinin Hōhō after purchasing the timber, these markings were no longer visible by around 1925.

- Company C showed no concern for maintaining Meinin Hōhō for the timber up until around 1935.

- Crucially, at the time H purchased the forest land (including the timber, as interpreted from the context) from the original co-owners in July 1933, there was no sufficient Meinin Hōhō existing in favor of Company C that could serve to publicly notify H of Company C's claimed ownership of the timber.

- In contrast, H, soon after his purchase, established his own Meinin Hōhō by erecting marking stakes and carving marks on trees, clearly indicating his ownership. These markings were still present when H later sold the land and timber to Company I.

- Conclusion on Priority: Therefore, the ownership of the standing timber acquired by H from the original co-owners took precedence over the ownership previously acquired by Company C (Y's predecessor). Consequently, Company X, having acquired its rights through H and Company I, had valid ownership of the timber. The appellate court's judgment affirming Company X's ownership was correct.

The appeal was unanimously dismissed.

Analysis and Implications

This 1961 Supreme Court judgment is a key decision that clarifies the nature and enduring requirements of "Meinin Hōhō" as a method for perfecting ownership of certain types of property, like standing timber, which can be treated separately from land under Japanese customary law.

- Meinin Hōhō as a Dynamic Requirement: The most significant principle established is that Meinin Hōhō is not a one-time act that provides perpetual protection. For it to be effective against a subsequent third party acquiring a conflicting interest, the method of clear recognition must continue to exist and be perceivable by third parties at the time the third party's interest arises. If the original markings or signs have disappeared or become ineffective as a notice, the initial perfection is lost with respect to new third parties.

- Analogy to Registration, but with a Key Difference: Meinin Hōhō serves a function analogous to registration for real property – it provides public notice of ownership. However, unlike formal registration in a public ledger (which, once made, generally remains effective unless formally cancelled, even if the physical register is damaged, as per other lines of case law discussed in the PDF commentary), Meinin Hōhō relies on physical manifestations that can degrade or be removed over time. This inherent lack of permanency compared to registry-based systems leads to the requirement of its continued existence.

- Responsibility of the Rights Holder: The ruling implicitly places a responsibility on the person claiming ownership through Meinin Hōhō to maintain that method of recognition if they wish to protect their rights against future third-party claimants. Failure to do so, leading to the disappearance or ineffectiveness of the Meinin Hōhō, can result in the loss of priority to a subsequent party who acquires an interest without being able to perceive the prior claim. The PDF commentary discusses this in terms of the "imputability" (帰責性 - kisekisei) to the rights holder if the public notice fails.

- Standing Timber as Separable Property: The case operates on the premise, well-established in Japanese law, that standing timber can be an object of ownership separate from the land itself, either through registration under the Standing Trees Act or, for unregistered timber, through the customary practice of Meinin Hōhō.

- Resolution of Competing Claims: In this "double sale" type scenario (where the timber was effectively sold first to Company C's predecessors and then, as part of the land, to H), the party who had an effective means of public notification (Meinin Hōhō for H; a prior, lapsed Meinin Hōhō for Company C's line) at the relevant time prevailed. H's establishment of a new, visible Meinin Hōhō, coupled with the absence of Company C's, was decisive.

This judgment underscores the practical realities and legal requirements associated with relying on customary methods of perfecting property rights like Meinin Hōhō. While recognized by law, their effectiveness is contingent on their continued ability to provide clear and unambiguous notice to the public, particularly at the critical juncture when a new third party is acquiring an interest in the property. It highlights a key difference in the durability of perfection between registry-based systems and those relying on physical manifestations.