Perfecting Claim Assignments in Japan: Is the "Certified Date" or Actual Arrival Time Decisive for Priority?

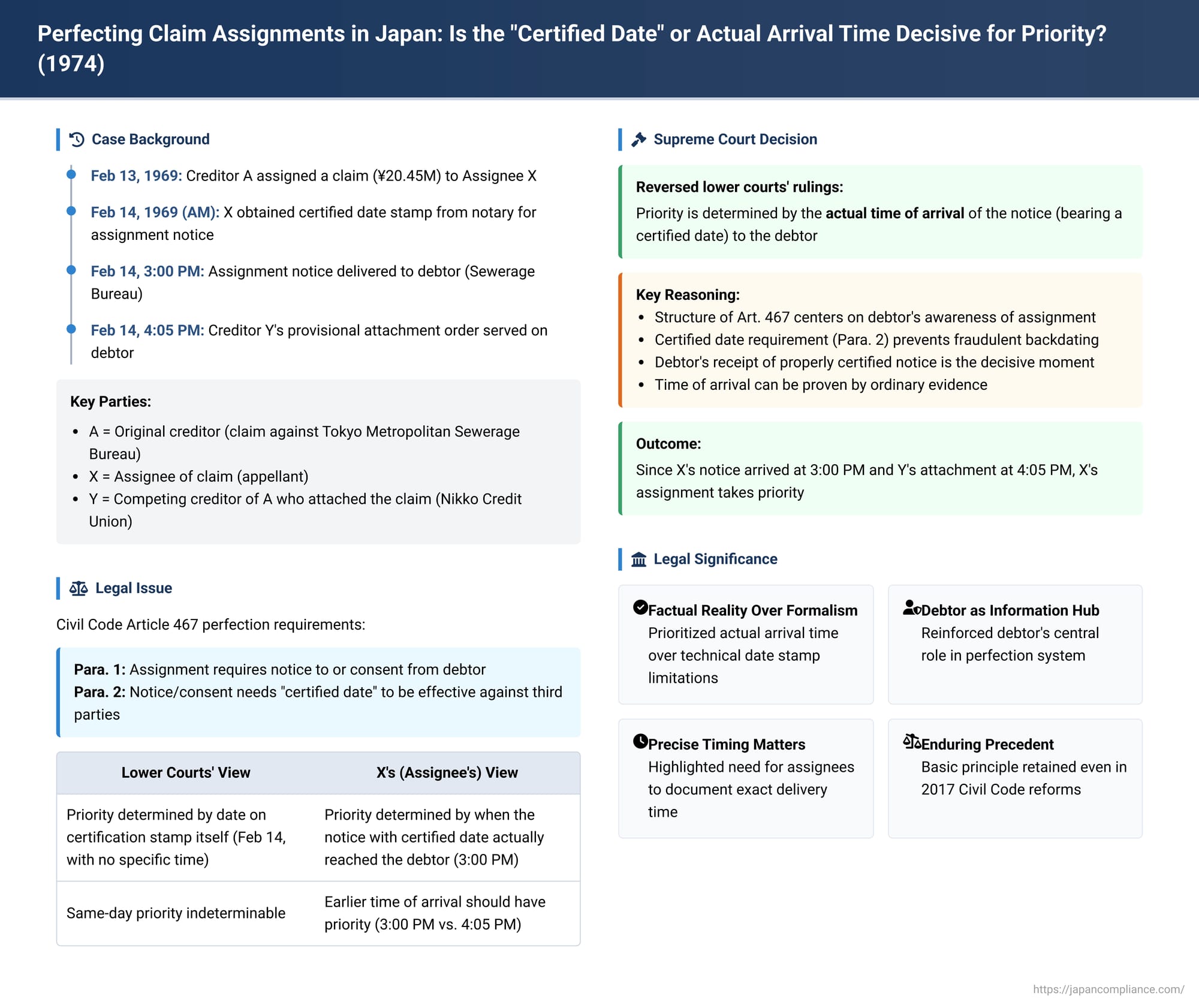

When a creditor assigns (sells or transfers) a monetary claim to another party, a crucial step is "perfecting" that assignment. Perfection determines the assignee's rights not only against the original debtor of the claim but, critically, against other third parties who might also have an interest in the same claim—such as another assignee in a double assignment, or a creditor who tries to seize the claim from the original assignor. For decades, Japanese law under Article 467 of the Civil Code has centered this perfection process on notifying the debtor of the claim or obtaining the debtor's consent, with an added requirement of a "certified date" (kakutei hizuke) for effectiveness against third parties. A Supreme Court of Japan decision on March 7, 1974 (Showa 47 (O) No. 596), provided a vital clarification: when it comes to a race for priority, is it the certified date itself that matters, or the precise moment the perfected notice reaches the debtor?

The System of Perfecting Claim Assignments in Japan (Article 467 Civil Code)

Before diving into the case, it's helpful to understand the basics of Article 467 of the Civil Code (as it stood at the time of the judgment and, in its core structure for this issue, largely continues today):

- Perfection against the Debtor and Third Parties (Paragraph 1): The assignment of a designated monetary claim cannot be asserted against the debtor of that claim or other third parties unless the assignor has given notice of the assignment to the debtor, or the debtor has consented to the assignment. This makes the debtor the central figure in the perfection process. The idea is that anyone interested in a claim (e.g., a potential buyer or an attaching creditor) would typically inquire with the debtor about its status.

- Requirement of a "Certified Date" for Third-Party Effectiveness (Paragraph 2): For the notice or consent to be effective against third parties other than the debtor (e.g., another assignee, an attaching creditor), it must be made by means of a document bearing a "certified date." A certified date is typically obtained from a notary public or through the content-certified mail system, providing an official, verifiable date for the document. The primary purpose of this requirement is to prevent fraudulent backdating of the notice or consent by the assignor and debtor, which could otherwise harm third parties who had already acted in reliance on the claim's prior status.

Facts of the 1974 Case: A Race Against Time – Assignment vs. Attachment

The 1974 case involved a classic "race for priority" between an assignee of a claim and a creditor seeking to attach that same claim:

- The Parties:

- A (BABA Nobukatsu): The original creditor who held a claim of approximately 20.45 million yen against the Director of the Tokyo Metropolitan Sewerage Bureau (the "Debtor").

- X (NAKAMURA Naohito): The party to whom A assigned this Claim.

- Y (Nikko Credit Union): A creditor of A, who sought to attach the Claim to satisfy A's debt to Y.

- The Assignment and Notice: Around February 13, 1969, A assigned the Claim to X. To perfect this, A prepared an assignment document addressed to the Debtor. This document received a certified date stamp from a notary public: "February 14, 1969." This dated document was then physically delivered to an employee of the Debtor (the Sewerage Bureau) at approximately 3:00 PM on February 14, 1969.

- The Provisional Attachment: On the very same day, February 14, 1969, Y obtained a provisional attachment order from the Tokyo District Court against the Claim A held against the Debtor. This court order was served on the Debtor (the Sewerage Bureau Director) at approximately 4:05 PM on February 14, 1969.

- The Dispute: X argued that since the notice of assignment was delivered to the Debtor (3:00 PM) before Y's provisional attachment order was served (4:05 PM), X's assignment should have priority. Y, and the lower courts, focused on the "certified date." The first instance court ruled that since the certified date (February 14) was the same as the date of attachment and service, X couldn't claim priority. The appellate court went further, stating that since X's certified date was merely "February 14" (without a specific time recorded by the notary beyond "between 12 PM and 6 PM" for the notice itself), it was impossible to determine the precise order of priority against Y's attachment served at 4:05 PM on that same day. Thus, both lower courts ruled against X.

X appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that Article 467(2) did not restrict proof of the timing of perfection solely to what was written in the certified date stamp.

The Supreme Court's Decisive Ruling: Arrival Time of Perfected Notice is Key

The Supreme Court overturned the lower courts' decisions and ruled in favor of X, the assignee. The Court's reasoning clarified the structure and purpose of Article 467:

- Reaffirmation of the System's Core – Debtor's Awareness: The Court reiterated that the fundamental design of Article 467(1) is to make the Debtor's awareness (through notice or consent) the linchpin for perfecting an assignment against both the Debtor and other third parties. This system relies on the Debtor being the primary source of information regarding the claim's status.

- Purpose of the Certified Date Requirement (Art. 467(2)): The requirement for a certified date on the notice or consent is not meant to alter this fundamental structure. Its specific purpose is to prevent the assignor and Debtor from colluding to fraudulently backdate the notice or consent to unfairly prejudice a third party who might have acted based on earlier information (e.g., in a scenario of double assignment).

- Priority Determined by Timing of Debtor's Awareness of the Perfected Act: Based on this structure, the Supreme Court held that when determining priority between competing claimants to a single claim (such as two assignees, or an assignee and an attaching creditor):

- Priority is NOT determined by simply comparing the "certified dates" stamped on the respective documents.

- Rather, priority is determined by the actual time that the notice (which must bear a certified date) reaches the Debtor, or the actual time of the Debtor's consent (which also must bear a certified date).

- The certified date is a prerequisite for the notice or consent itself to be valid against third parties, but the chronological order of perfection for priority purposes is established by when the Debtor becomes aware of this perfected act.

- Proof of Arrival Time: The Court implicitly accepted that the actual time of arrival of the notice to the Debtor can be proven by ordinary evidence, not solely by what might (or might not) be recorded as part of the certified date.

- Outcome in the Case:

- A's assignment notice to the Debtor bore a certified date of February 14.

- This notice was physically delivered to and received by an employee of the Debtor at 3:00 PM on February 14.

- Y's provisional attachment order was served on the Debtor at 4:05 PM on February 14.

- Since X's perfected notice (notice bearing a certified date) arrived at the Debtor earlier than Y's attachment order was served, X's assignment took priority over Y's attachment.

The Supreme Court therefore found that the lower courts had misinterpreted Article 467 by focusing incorrectly on the certified date itself as the sole determinant of priority or by deeming priority indeterminable if dates were the same.

Significance of the "Arrival Time" Rule

This 1974 ruling by the Supreme Court had (and continues to have) significant implications:

- Clarity Over Formalism: It prioritized the factual reality of when the Debtor became aware of the perfected assignment over a potentially incomplete or ambiguous formality (the date stamp on the certified document, which might not include a precise time).

- Reinforcing the Debtor as the Information Hub: The decision underscored that the Debtor's knowledge, triggered by the arrival of a properly certified notice or the giving of a certified consent, is the pivotal moment for establishing an assignee's rights against other third parties.

- Practical Implications for Assignees: It highlighted the need for assignees not only to ensure their notice of assignment (or the debtor's consent) bears a certified date but also to effect prompt delivery to the debtor and be prepared to prove the actual time of this arrival if priority disputes arise.

Challenges and Evolution of the Perfection System in Japan

While the 1974 Supreme Court decision clarified the mechanics of Article 467, legal commentators have long pointed out inherent weaknesses in a perfection system that relies so heavily on the debtor:

- The debtor is generally under no legal obligation to respond to inquiries from potential assignees or other third parties, or they may cite confidentiality.

- The debtor is burdened with the potentially complex task of determining the precise order of arrival of multiple notices or attachments.

- In many modern financing scenarios (e.g., assignment of future claims, securitization, assignment for security purposes), there is a strong commercial need to perfect assignments against third parties without necessarily involving the primary debtor in the perfection process at that stage.

These practical needs led to the development of alternative perfection mechanisms in Japan, notably the claim assignment registration system under special laws (Act on Special Provisions for a Shōmeisho concerning the Perfection of Assignment of Claims). This system allows for the perfection of certain claim assignments against third parties by public registration, separating it from the notice to or consent from the debtor (which remains necessary for perfection against the debtor).

Despite these developments and discussions during the extensive 2017 Civil Code reforms about potentially overhauling Article 467's general perfection rules (e.g., by moving towards a registration-only system for third-party effectiveness), the fundamental notice/consent mechanism, as interpreted by this 1974 Supreme Court judgment, was ultimately retained as the general rule for ordinary claim assignments. This was due in part to the perceived advantages of the existing system's relative simplicity and low cost for many common transactions. However, the legislative challenges and the evolution of commercial practice continue to shape this area of law. (Notably, France, from whose legal tradition Japan's notice/consent system was originally derived, abandoned its debtor-centric perfection model in 2016.)

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1974 judgment in this "Third Party Objection Case" remains a foundational piece of jurisprudence for understanding how claim assignments are perfected against third parties in Japan under Article 467 of the Civil Code. By decisively establishing that priority is determined by the actual time of arrival of a notice (bearing a certified date) to the debtor—or the time of the debtor's consent (bearing a certified date)—rather than solely by the certified date stamp itself, the Court emphasized the debtor's awareness as the critical element. This ruling underscores the importance of both obtaining a certified date and ensuring prompt, provable delivery of notice to the debtor when dealing with claim assignments in Japan.