Paying the Price for Environmental Protection: Japan's Supreme Court on Court Fees in Multi-Plaintiff Revocation Lawsuits

Date of Decision: October 13, 2000

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

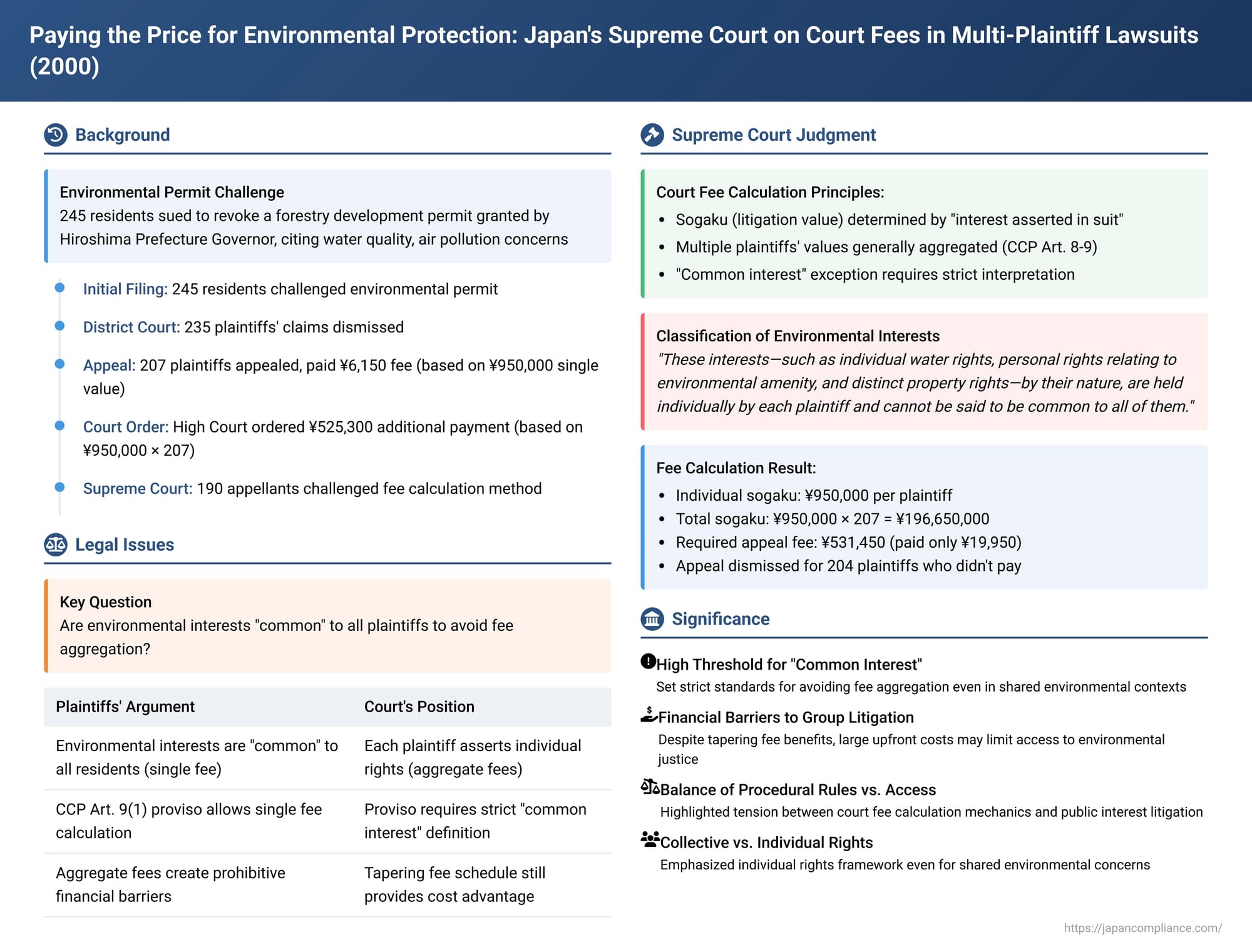

On October 13, 2000, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a significant decision addressing a critical procedural aspect of public interest litigation: the calculation of court filing fees when a large number of plaintiffs jointly file an administrative lawsuit. The case specifically concerned a suit brought by numerous residents seeking the revocation of a governmental permit for land development due to environmental concerns. The central question was how to determine the "value of the object of litigation" (sogaku), a figure crucial for calculating court fees, and whether the collective nature of the plaintiffs' environmental interests could be considered "common" so as to avoid the aggregation of individual values, thereby reducing the overall fee burden. This decision clarified the application of complex procedural rules for calculating court fees in multi-plaintiff administrative actions, emphasizing the individual nature of the asserted interests even in environmental contexts, and consequently impacting the financial accessibility of such group litigation.

I. The Environmental Dispute and the Joint Lawsuit

The case originated from a local environmental dispute triggered by a prefectural government's decision to permit land development.

The Development Permit:

Y, the Governor of Hiroshima Prefecture, granted a permit to a private company, A, for a land development project within a forested area. This permit was issued based on the authority vested in the governor by Article 10-2 of Japan's Forestry Act.

The Plaintiffs' Concerns and Allegations:

A large group of 245 local residents (collectively referred to as X), who lived in the vicinity of the area designated for development, joined together to file a lawsuit. Their objective was to seek a court order revoking the permit granted by Governor Y to Company A. The residents alleged that the proposed development activities would lead to a range of adverse environmental consequences, including:

- Deterioration of water quality in the surrounding region.

- Significant changes in local water volume and flow.

- Air pollution.

- Other forms of environmental degradation detrimental to their living conditions.

Alleged Harm to Individual Rights:

X, the resident plaintiffs, claimed that these anticipated environmental impacts would directly infringe upon their individually held legal rights. These rights included their water rights (e.g., for domestic or agricultural use), their personal rights (which in Japanese jurisprudence can encompass the right to a healthy and peaceful environment), and their rights as owners of real estate in the affected area.

Grounds for Seeking Revocation:

The residents' lawsuit asserted that the permit granted by Governor Y was illegal on multiple grounds. They claimed substantive illegalities, arguing that conditions existed which should have led to a refusal of the permit under the criteria set forth in Article 10-2, paragraph 2 of the Forestry Act. Additionally, they alleged procedural illegalities, including a claim that the permit was issued without first obtaining the necessary consent from them as affected local residents.

II. The Procedural Wrangle Over Court Fees

The path to a substantive hearing on the environmental claims was significantly complicated by a dispute over the correct amount of court filing fees.

First Instance Outcome:

The lawsuit was initially heard by the District Court. For reasons not detailed in the Supreme Court's fee-related decision but forming the backdrop to the appeal, the District Court dismissed the claims of 235 of the original 245 plaintiffs.

Appeal to the High Court and Initial Fee Payment:

Following the District Court's judgment, 207 of the plaintiffs whose claims had been dismissed decided to appeal this adverse decision to the High Court. When filing their joint notice of appeal (kōsojō), these 207 appellants attached revenue stamps (the method of paying court fees in Japan) totaling JPY 6,150. This sum was calculated based on their assumption that the "value of the object of litigation" (sogaku) for their collective appeal was JPY 950,000. At that time in Japan, under the Civil Procedure Costs Act, JPY 950,000 was the prescribed deemed sogaku for certain categories of non-pecuniary claims or for claims where assessing a precise monetary value was considered extremely difficult.

High Court Presiding Judge's Order for Additional Fees:

The Presiding Judge of the High Court, upon reviewing the appeal documents, disagreed fundamentally with the appellants' calculation of the sogaku and the consequently paid fee. The judge took the position that the correct sogaku for the joint appeal should be determined by multiplying the deemed individual sogaku of JPY 950,000 by the total number of appellants, which was 207. This method resulted in a vastly larger aggregate sogaku (JPY 950,000 x 207 = JPY 196,650,000). Based on this much higher aggregated sogaku, the total required appeal fee was calculated to be JPY 531,450. The judge therefore issued an order directing the appellants to pay the substantial shortfall of JPY 525,300.

Partial Additional Payment and Subsequent Dismissal of Appeal:

In response to this judicial order, the appellants submitted an additional JPY 13,800 in revenue stamps. They specified that this additional payment was intended to cover the appeal fees for three particular appellants from their group of 207. However, the much larger remaining portion of the assessed fee, corresponding to the other 204 appellants, was not paid. These appellants maintained their original stance that their initial calculation based on a single JPY 950,000 sogaku for the entire group was correct. Due to the non-payment of the full fee as ordered, the High Court Presiding Judge issued a subsequent order dismissing the appeal petition for these 204 appellants.

Appeal to the Supreme Court on the Procedural Issue:

From this group of 204, a cohort of 190 appellants sought and were granted permission to appeal the High Court Presiding Judge's dismissal order to the Supreme Court of Japan. Their central legal argument before the Supreme Court was that the interests they asserted in seeking the revocation of the environmental permit were "common" to all of them. If their interests were indeed deemed "common," then under Japanese civil procedure rules, the sogaku for their joint appeal should be a single JPY 950,000, applicable to the entire group, which would mean their initial fee payment of JPY 6,150 was sufficient.

III. The Supreme Court's Decision on Calculating Litigation Value

The Supreme Court, in its carefully reasoned decision, addressed the principles governing the calculation of the "value of the object of litigation" (soshō no mokuteki no kagaku, often abbreviated as sogaku) and the corresponding court filing fees, particularly in the context of lawsuits involving multiple plaintiffs.

A. General Principles for Sogaku and Court Fees

- "Interest Asserted in the Suit": The Court began its analysis by reiterating a fundamental principle: the sogaku, which serves as the crucial basis for calculating the filing fees for both initiating lawsuits and lodging appeals, is to be determined by the "interest asserted in the suit" (uttae de shuchō suru rieki) by the plaintiff or plaintiffs. This "interest" is generally understood in Japanese civil procedure to mean the economic or other tangible benefit that the plaintiff would obtain if their claim were to be fully successful and the court's judgment were realized.

- Aggregation of Claims as the Default Rule: When a single lawsuit encompasses multiple distinct claims—whether these are multiple claims brought by a single plaintiff or individual claims brought by several joint plaintiffs—the general rule under Japanese law is that the monetary values attributed to these individual claims are aggregated (summed up) to arrive at the total sogaku for the entire suit. This principle of aggregation is grounded in provisions found in Japan's Civil Procedure Costs Act (specifically, Article 4, paragraph 1) and the Code of Civil Procedure (CCP) (Article 8, paragraph 1, and Article 9, paragraph 1).

- Application to Joint Plaintiffs: Based on this general rule of aggregation, the Supreme Court affirmed that, as a matter of principle, even when a large number of individuals decide to jointly file a single lawsuit, the total sogaku for that action is to be calculated by adding together the value of the distinct interest asserted by each individual plaintiff. The court filing fee payable is then determined based on this aggregated total sogaku, by applying the tiered fee schedule provided in Schedule 1 of the Civil Procedure Costs Act.

B. The Tapering Fee Structure and the Benefit of Joint Filing

The Supreme Court then pointed to an important and relevant feature of the fee schedule contained in the Civil Procedure Costs Act: this schedule employs a tapering or degressive system. This means that while the absolute amount of the filing fee increases with a larger sogaku, the rate at which the fee increases becomes progressively smaller for higher sogaku amounts. In other words, the fee as a percentage of the sogaku tends to decrease for very high-value claims.

- As a direct consequence of this tapering fee structure, the Court explained, even when the individual sogaku amounts for multiple plaintiffs are aggregated to calculate the total sogaku, each individual plaintiff in a joint lawsuit effectively ends up bearing a lower personal fee burden compared to what they would have had to pay if they had each filed the exact same lawsuit independently. The Supreme Court explicitly highlighted this aspect of the fee system, partly to counter arguments from the appellants that its interpretation requiring aggregation would make joint litigation prohibitively expensive.

C. The "Common Interest" Exception to the Aggregation Rule

The Supreme Court subsequently addressed a critical exception to the general rule of sogaku aggregation. This exception is found in the proviso to Article 9, paragraph 1 of the Code of Civil Procedure.

- This proviso stipulates that if the "interest asserted in the suit is common to each claim" involving joint plaintiffs (or common to multiple claims by a single plaintiff), then the aggregation of their individual sogaku amounts is not required. In such exceptional cases where a "common interest" is recognized, all the joint plaintiffs, regardless of their total number, would only need to bear the court fee that corresponds to the value of a single plaintiff's claim (or the value of that common interest if assessed as a single quantum).

- The PDF commentary provides useful background here, clarifying that this "common interest" proviso was formally introduced into the CCP through amendments in 1996. However, this amendment was largely a codification of principles that had already been established in prior case law, including a notable 1978 Supreme Court ruling concerning residents' litigation (a type of public interest lawsuit under the Local Autonomy Act) which had denied the need for aggregation based on the commonality of the interest being pursued.

D. Application of these Principles to X's Environmental Lawsuit

The Supreme Court then applied these general principles and the "common interest" exception to the specific facts of X's environmental lawsuit.

- Nature of the Plaintiffs' Asserted Interests: The Court characterized the "interest asserted in the suit" by X (the resident plaintiffs) as the benefit that each individual plaintiff stood to recover if the administrative permit for the land development project were to be judicially revoked. More concretely, these were identified as interests forming part of each plaintiff's individual water rights, personal rights (such as the right to enjoy a healthy environment or freedom from nuisance), and their rights as owners of real estate in the potentially affected area.

- Difficulty in Monetary Valuation and the Use of a Deemed Sogaku: The Supreme Court readily acknowledged that assigning a precise monetary value to such environmental and personal rights is "extremely difficult". Consequently, it affirmed the approach of using a deemed sogaku. For the interest asserted by each individual plaintiff, this deemed sogaku was JPY 950,000, pursuant to the provisions of Article 4, paragraph 2 of the Civil Procedure Costs Act (as that Act stood at the time of the case). This statutory provision allows for a standardized, deemed value to be used for non-pecuniary claims or for pecuniary claims where a precise financial valuation proves to be exceptionally hard. The PDF commentary accompanying this case notes that this practice of applying a deemed sogaku in environmental administrative revocation suits was already a common approach even before the 1996 CCP revision explicitly incorporated the "extremely difficult to calculate" language into the text of the Civil Procedure Costs Act.

- The "Common Interest" Exception Held Inapplicable to This Case: This was the determinative point of the Supreme Court's decision. After analyzing the nature of the rights asserted by X, the Supreme Court ruled that these interests—such as individual water rights, personal rights relating to environmental amenity, and distinct property rights—"by their nature, are held individually by each plaintiff and cannot be said to be common to all of them". Because the Court found the interests to be primarily individual, it concluded that the exception to aggregation found in CCP Article 9, paragraph 1, proviso, did not apply to this case.

- Conclusion on Sogaku Calculation for X's Appeal: Given that the Court deemed the asserted interests to be individual rather than "common" in the sense required by the CCP proviso, it logically followed that the total sogaku for X's lawsuit (and therefore for their appeal) had to be calculated by aggregating the JPY 950,000 deemed value for each of the appealing plaintiffs. The fee for the appeal would then be determined based on this large aggregated sogaku, calculated in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Civil Procedure Costs Act (which typically involve the first instance fee for that sogaku, multiplied by 1.5 for an appeal, and then halved in cases like this where the first instance judgment had dismissed the original suit).

E. Rejection of the Appellants' Hardship Argument

The appellants had forcefully argued that requiring the aggregation of individual sogaku values in a case with over 200 plaintiffs would result in an astronomically high total sogaku, leading to a prohibitively expensive filing fee. This, they contended, would make it extremely difficult, if not impossible, for large groups of ordinary residents to jointly file lawsuits or appeals to protect their environmental rights and access justice.

- The Supreme Court countered this argument by emphasizing the effect of the tapering fee schedule previously mentioned. It performed a comparative calculation: if each of the 207 plaintiffs had filed their appeal individually (assuming a JPY 950,000 sogaku per individual appeal), each would have had to pay a fee of JPY 6,150. However, by appealing jointly, even with the aggregation of the sogaku leading to a very high total, the tapering effect of the fee schedule meant that each of the 207 appellants would only need to bear an average fee of approximately JPY 2,567.

- Based on this calculation, the Supreme Court concluded that the joint filing, even under its interpretation requiring aggregation, still offered a significant cost advantage per plaintiff when compared to the alternative of numerous individual filings. Therefore, the Court found that the appellants' argument of undue hardship and denial of access to justice was "not valid" in this specific instance.

Final Decision of the Supreme Court:

Based on this comprehensive reasoning, the Supreme Court concluded that the High Court Presiding Judge's original order, which had required the payment of additional fees based on the aggregated sogaku, and the subsequent dismissal of the appeal petition for non-payment of these fees, were both lawful and correct under the prevailing statutes. The appeal lodged by the 190 residents against this dismissal order was therefore rejected by the Supreme Court.

IV. Discussion and Implications

The Supreme Court's 2000 decision on court fees in multi-plaintiff environmental lawsuits has several important implications and has been a subject of legal commentary.

The "Common Interest" Threshold in Environmental Cases:

- This Supreme Court decision established a significant, and arguably high, threshold for what constitutes a "common interest" for the purposes of avoiding sogaku aggregation under CCP Article 9(1) proviso, particularly in the context of environmental lawsuits where individual rights are asserted collectively. By classifying interests such as the individual enjoyment of unimpaired water quality, clean air, and the undisturbed use of private property as primarily "individual" in nature—even when a large group seeks to protect a shared environmental resource—the Court made it more likely that the sogaku in such cases would be calculated through aggregation.

- The PDF commentary associated with this line of cases highlights that this particular aspect of the decision has faced criticism from some legal scholars. These critics often argue that many environmental benefits, such as the enjoyment of clean air or unpolluted water in a specific locale, are inherently non-exclusive goods. The use or enjoyment of these environmental benefits by one resident does not necessarily diminish their availability or enjoyment by another; in this crucial sense, they are "commonly" enjoyed by all residents in the affected community. The contention, therefore, is that if these are indeed common benefits that the plaintiffs are collectively seeking to protect through the revocation of a permit that threatens this common environment, the legal "interest" in pursuing that revocation could also logically be viewed as "common" to all plaintiffs.

- The commentary further points to a potential doctrinal tension: if, for instance, a residents' lawsuit framed as seeking an injunction (a type of "demand for performance" litigation, which sometimes falls under different fee calculation paradigms or is more readily seen as pursuing a single, indivisible outcome) to halt a polluting activity could potentially avoid sogaku aggregation based on a perceived common interest in preventing widespread harm, it becomes more challenging to articulate a clear and consistent legal reason why an administrative revocation suit—aimed at achieving a very similar environmental protection outcome by annulling the permit that allows the harmful activity—should necessarily lead to a different conclusion on the "common interest" question and thus mandate aggregation.

Impact on Access to Environmental Justice:

- While the Supreme Court correctly and numerically demonstrated that a joint filing, even with sogaku aggregation, results in a per-plaintiff cost saving compared to the hypothetical scenario of numerous individual lawsuits, due to Japan's tapering fee scale, the practical reality is that the requirement to aggregate the sogaku for a large number of plaintiffs can still lead to an extremely substantial initial total sogaku. This, in turn, can translate into a very large absolute sum for the total filing fee that must be paid upfront.

- Such a large initial financial outlay can remain a significant, and potentially insurmountable, barrier for grassroots community groups, unincorporated associations, or large numbers of ordinary citizens who may wish to collectively challenge administrative decisions that adversely affect their shared environment.

- The PDF commentary implicitly acknowledges this broader concern by noting that the level of court filing fees can directly influence practical access to the judicial system, and that lawsuits of considerable social significance might face higher initial hurdles if their sogaku becomes exceptionally large due to the number of participants or the nature of the claim.

Policy Considerations in Fee Setting:

- The case also subtly touches upon the intricate balance that must be struck between purely legalistic interpretations of procedural rules and the underlying policy objectives that are inherent in the legislative setting of court fees. The PDF commentary wisely offers a caution that while legal theory regarding concepts such as the "interest in suit" is vital, the rules for calculating court fees also possess an undeniable policy dimension. There is a potential risk if substantive legal theories or procedural doctrines become unduly "dragged down," constrained, or distorted by the practical imperatives of arriving at a particular fee structure or revenue model for the court system.

- For instance, the commentary raises a nuanced and thought-provoking point: while making it financially advantageous for very large numbers of plaintiffs to join a single lawsuit (e.g., through a highly favorable interpretation of "common interest" that dramatically lowers fees) might, on its face, seem to promote broader access to justice, it could also inadvertently create tension with other important legal principles, such as the fundamental respect for each individual plaintiff's autonomous decision-making regarding their own litigation strategy, objectives, and willingness to bear risks.

Clarity for Future Litigants:

- Despite the potential criticisms and ongoing debates it may have spurred, the Supreme Court's 2000 decision did provide a clear, albeit arguably restrictive, directive for the calculation of sogaku and court fees in this specific type of multi-plaintiff administrative revocation suit. It strongly signaled that the "common interest" exception to sogaku aggregation is to be interpreted narrowly, and that individual rights, even when asserted collectively by many people in a shared environmental context, are likely to be treated as predominantly individual interests for the purpose of court fee calculation, thus generally leading to the aggregation of their deemed values. This provides a degree of predictability, though perhaps not the outcome desired by all public interest litigants.

V. Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's decision of October 13, 2000, offers critical, if for some, controversial, guidance on the complex issue of calculating court filing fees for administrative lawsuits brought by multiple plaintiffs, particularly within the vital domain of environmental protection.

By concluding that the individual environmental and property-related interests asserted by a large group of residents seeking the revocation of a development permit are not "common" in the specific legal sense required to avoid the aggregation of each plaintiff's deemed litigation value (sogaku), the Court established that filing fees in such collective actions would generally be based on the sum of these individual values.

While the Court rightly pointed out that Japan's tapering fee scales still afford a per-plaintiff cost saving in joint lawsuits compared to a scenario of numerous individual actions, the decision nonetheless underscores the potential for substantial upfront litigation costs when large communities mobilize to challenge administrative decisions through the courts. This outcome continues to fuel an important debate in Japan concerning the optimal balance between procedural rules for cost allocation, the fundamental principle of access to justice, and the effective legal protection of collective or diffuse interests, such as environmental quality.