Paying Tax on Property Not Yours? Japanese Supreme Court on Unjust Enrichment and Fixed Assets Tax

Date of Judgment: January 25, 1972

Case Name: Claim for Reimbursement of Advanced Money (昭和46年(オ)第766号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

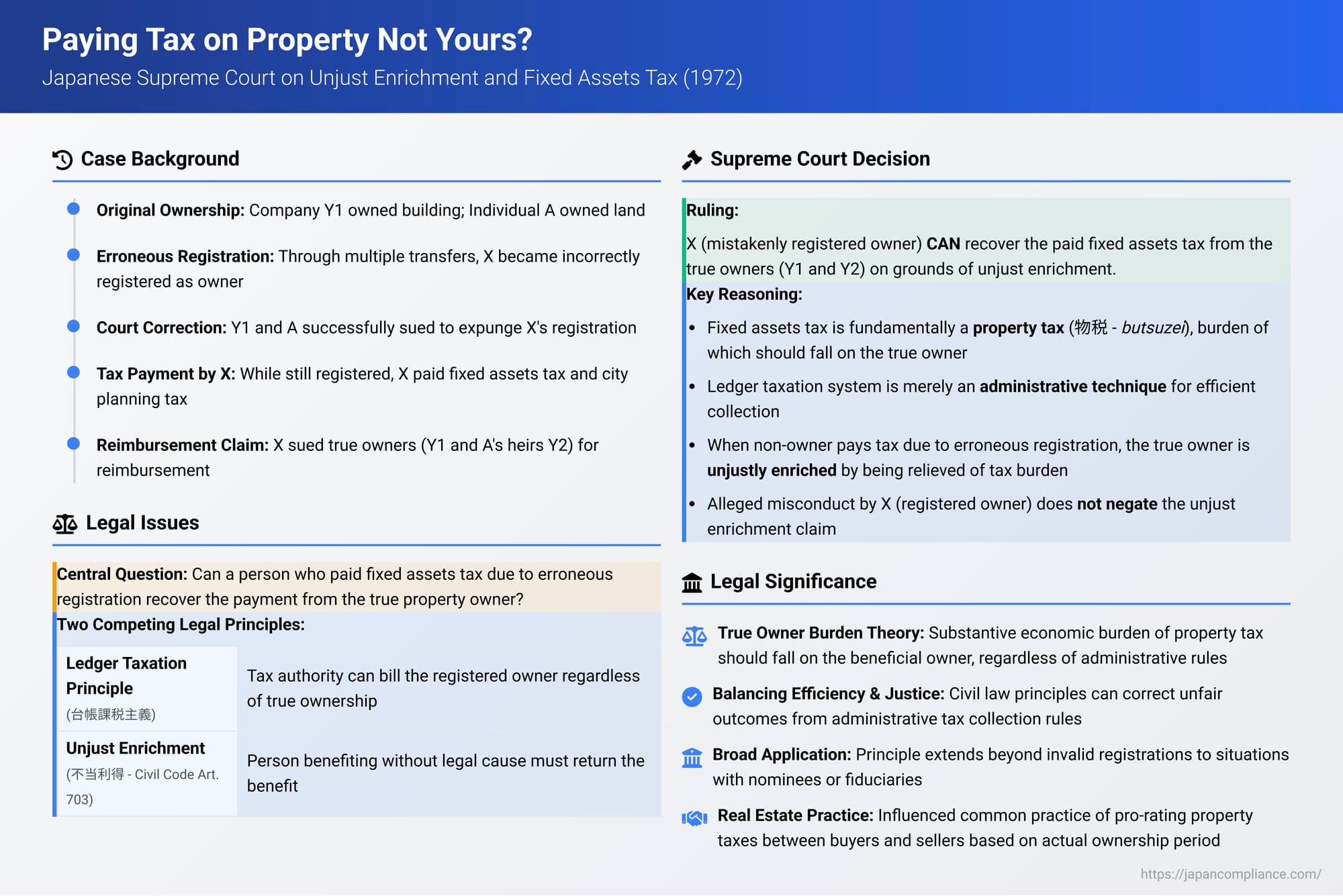

In a pivotal decision on January 25, 1972, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the rights of a person who, due to an erroneous property registration, paid fixed assets tax and city planning tax on real estate they did not truly own. The Court affirmed that such a person could recover the tax amounts paid from the actual owners of the property under the principle of unjust enrichment. This case highlights the interplay between Japan's "ledger taxation principle" for fixed assets tax and fundamental concepts of fairness in private law.

The Case of Mistaken Identity (in Property Registration)

The dispute involved a building ("the subject building") and the land upon which it stood ("the subject land"). The subject building was originally owned by Company Y1, and the subject land was originally owned by an individual, A (the predecessor of Y2 et al., who inherited his rights and obligations).

Through a series of events that occurred without the knowledge of the true owners (Y1 and A), the ownership registration for both the land and building was successively and erroneously transferred through several intermediaries (B, then C and D), ultimately culminating in the registration of X as the owner.

The true owners, Y1 and A, initiated legal action against C, D, and X, seeking the cancellation of these incorrect ownership registrations. Their lawsuit was successful, and a court judgment became final and binding, confirming that Y1 and A were indeed the true owners of the building and land, respectively, and ordering the erroneous registrations in X's name to be expunged.

However, the court-ordered correction of the property register to remove X's name was not immediately carried out. During this interim period, A passed away, and his heirs, Y2 et al., succeeded to his rights and interests. Importantly, while X remained the owner of record, X paid the fixed assets tax (固定資産税 - kotei shisan zei) and city planning tax (都市計画税 - toshi keikaku zei) levied on the subject land and building for several years.

Subsequently, X filed a lawsuit against Y1 and Y2 et al. (as the now judicially confirmed true owners). X sought reimbursement for the taxes he had paid, arguing that these taxes were fundamentally the responsibility of the true owners and that, by X having paid them, Y1 and Y2 et al. had been unjustly enriched.

The defendants, Y1 and Y2 et al., countered these claims. They argued that X had failed to fulfill his obligation to effect the cancellation of the erroneous registration following the definitive court judgment. They further contended that X had, during this period, effectively usurped the property and exercised de facto ownership rights over it. Therefore, they claimed, X paid the taxes as a consequence of his own actions and improper use of the property, making the application of unjust enrichment principles (under Article 703 of the Civil Code, which they argued should consider the "substantive economic relations") inappropriate in this instance.

The first instance court (Tokyo District Court) had ruled partially in favor of X. It reasoned that although fixed assets tax and city planning tax are levied on the registered owner for "technical considerations in taxation" (i.e., administrative convenience), the ultimate burden of these property-based taxes should fall on the true owner. Thus, when a non-owner like X pays the tax due to an incorrect registration, the true owners (Y1 and A's estate) are relieved of a burden they should have borne, resulting in their unjust enrichment at X's expense. The court found this conclusion to be in line with principles of fairness (衡平の原則 - kōhei no gensoku). The Tokyo High Court, on appeal, fully adopted the first instance court's reasoning and dismissed the appeal by Y1 and Y2 et al.. Y1 and Y2 et al. then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Framework: Fixed Assets Tax, Ledger Taxation, and Unjust Enrichment

Understanding this case requires familiarity with three key legal concepts in Japan:

- Fixed Assets Tax (and City Planning Tax): Fixed assets tax is a local tax levied by municipalities on the assessed value of land, houses, and depreciable business assets. City planning tax is often levied concurrently on properties within designated city planning zones. The Supreme Court noted that fixed assets tax is fundamentally a "property tax" (butsuzei) – a tax imposed on the asset value itself – and, in principle, its burden should be borne by the owner of the property.

- Ledger Taxation Principle (Daichō Kazei Shugi): For practical administrative efficiency in tax collection, the Japanese Local Tax Act adopts what is known as the "ledger taxation principle" (台帳課税主義 - daichō kazei shugi). Under this principle, the person registered as the "owner" in the official property ledgers (at the time of this case, the Land Ledger or Supplementary Land Tax Ledger for land, and the House Ledger or Supplementary House Tax Ledger for buildings) as of a specific assessment date (typically January 1st) is legally deemed the taxpayer liable for the fixed assets tax for the relevant fiscal year. The constitutionality of this principle had been upheld by the Supreme Court in earlier cases.

- Unjust Enrichment (Civil Code Article 703): This is a general principle of private law stipulating that a person who, without legal cause, benefits from the property or labor of another, thereby causing loss to that other person, is obliged to return such benefit to the extent it still exists.

The central legal tension in this case was whether the Local Tax Act's ledger taxation principle—which legally obligates the registered owner to pay the tax—precludes a claim of unjust enrichment under the Civil Code against the true owner, who ultimately should bear the economic burden of a tax on their property.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: True Owner Bears the Ultimate Burden

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by Y1 and Y2 et al., thereby upholding the lower courts' decisions which had found in favor of X's unjust enrichment claim.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Fundamental Nature of Fixed Assets Tax: The Court reiterated that fixed assets tax is a tax on the value of the property itself (a butsuzei), and its burden, in principle, rests with the actual owner of that property.

- Ledger Taxation as an Administrative Technique: The Local Tax Act's adoption of the ledger taxation system—taxing the person registered as the owner—is based on "technical considerations in taxation" aimed at administrative efficiency and certainty in tax collection. It provides a clear and convenient basis for levying the tax.

- Unjust Enrichment of the True Owner: When a person who is not the true owner of land or a house is, due to an erroneous registration, formally listed as the owner in the official ledgers and consequently is assessed and pays the fixed assets tax, the true owner is thereby relieved of a tax burden that they, as the actual owner, should have borne. In relation to the registered (but not true) owner who made the payment, the true owner has been "unjustly enriched" by an amount equivalent to the tax paid.

- Applicability to City Planning Tax: The Court stated that this same principle applies to city planning tax, which is of a similar nature to fixed assets tax.

- Irrelevance of Registered Owner's Conduct: The Supreme Court explicitly addressed the appellants' argument that X's own conduct—specifically, his alleged failure to promptly carry out the court-ordered cancellation of his erroneous registration and his purported exercise of de facto ownership over the property—should negate his unjust enrichment claim. The Court affirmed the High Court's finding that such circumstances "do not affect the existence of the said claim for reimbursement".

Therefore, the Supreme Court found that the lower courts' judgments, which recognized X's claim based on the principle of unjust enrichment to the extent determined, were appropriate and legally sound.

Analysis: Balancing Tax Collection Efficiency with Fairness

This Supreme Court decision is significant for establishing a clear legal precedent regarding the interplay between the administrative rule of ledger taxation and the equitable principles of unjust enrichment in private law. Legal commentary has analyzed this ruling through various theoretical lenses:

- The "True Owner Burden Theory" (Shin no Shoyūsha Futan Setsu): The Court's decision implicitly and strongly supports the "true owner burden theory". This theory posits that, notwithstanding administrative rules that might designate the registered owner as the formal taxpayer for collection purposes, the substantive economic burden of a tax intrinsically linked to property ownership (like fixed assets tax) should ultimately fall upon the person who is the true, beneficial owner of that property.

- Limiting the Reach of Ledger Taxation into Private Law: The judgment effectively prevents the technical rule of ledger taxation from creating substantively unfair or inequitable outcomes in private law disputes between the party mistakenly registered as owner and the actual true owner. While the tax authorities can rely on the register to identify the party legally liable for payment, this does not extinguish the underlying equitable claim the payer might have against the true beneficiary of that payment (the true owner whose property tax was discharged). In this sense, the unjust enrichment principle acts as a "brake" or corrective mechanism against potentially unreasonable private law consequences flowing from a strict application of the administrative tax collection rule.

- Broad Applicability Beyond Invalid Registrations: While this case involved an initially invalid chain of title leading to X's erroneous registration, the underlying reasoning—that the true owner should bear the tax—suggests that the principle could extend beyond cases of void registrations. For example, it might apply to situations where a validly registered owner is merely a nominee, trustee, or other fiduciary holding the property for a different beneficial owner who should equitably bear the property's tax burden.

- Reflection in Real Estate Practice: The fundamental idea that the true owner bears the economic burden of fixed assets tax often informs common practices in real estate transactions in Japan. For instance, when a property is sold mid-year, it is customary for the fixed assets tax (which is assessed on the owner as of January 1st for the entire fiscal year) to be contractually pro-rated between the buyer and seller, reflecting an understanding that the burden should align with the period of actual ownership or benefit, regardless of who is the formally assessed taxpayer for that year.

The Supreme Court's decision in this 1972 case has been influential in subsequent jurisprudence. For instance, a later Supreme Court judgment in 2014 (Sup. Ct. Sept 25, 2014, Minshu Vol. 68, No. 7, p. 722), which dealt with the taxation of newly constructed houses not yet registered in the tax ledgers as of the assessment date, referenced this 1972 decision, indicating that its core reasoning about the true owner's underlying responsibility remained consistent and was not contradicted by the specifics of the later case.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1972 judgment provides a crucial affirmation of equitable principles within the framework of Japan's fixed assets tax system. It establishes that while tax authorities can, for administrative efficiency, rely on official property registers to identify the party legally liable for paying fixed assets tax, a person who is mistakenly registered as the owner and consequently pays such tax has a right to recover those payments from the true owner on the grounds of unjust enrichment. This decision underscores the principle that the ultimate economic burden of a tax intrinsically tied to property ownership should rest with the true beneficial owner, thereby preventing the technicalities of tax collection from producing substantively unjust outcomes in private law relationships.