Paying for 'Smooth' Shareholder Meetings: A 1969 Japanese Supreme Court Case on Sōkaiya Bribery

Judgment Date: October 16, 1969

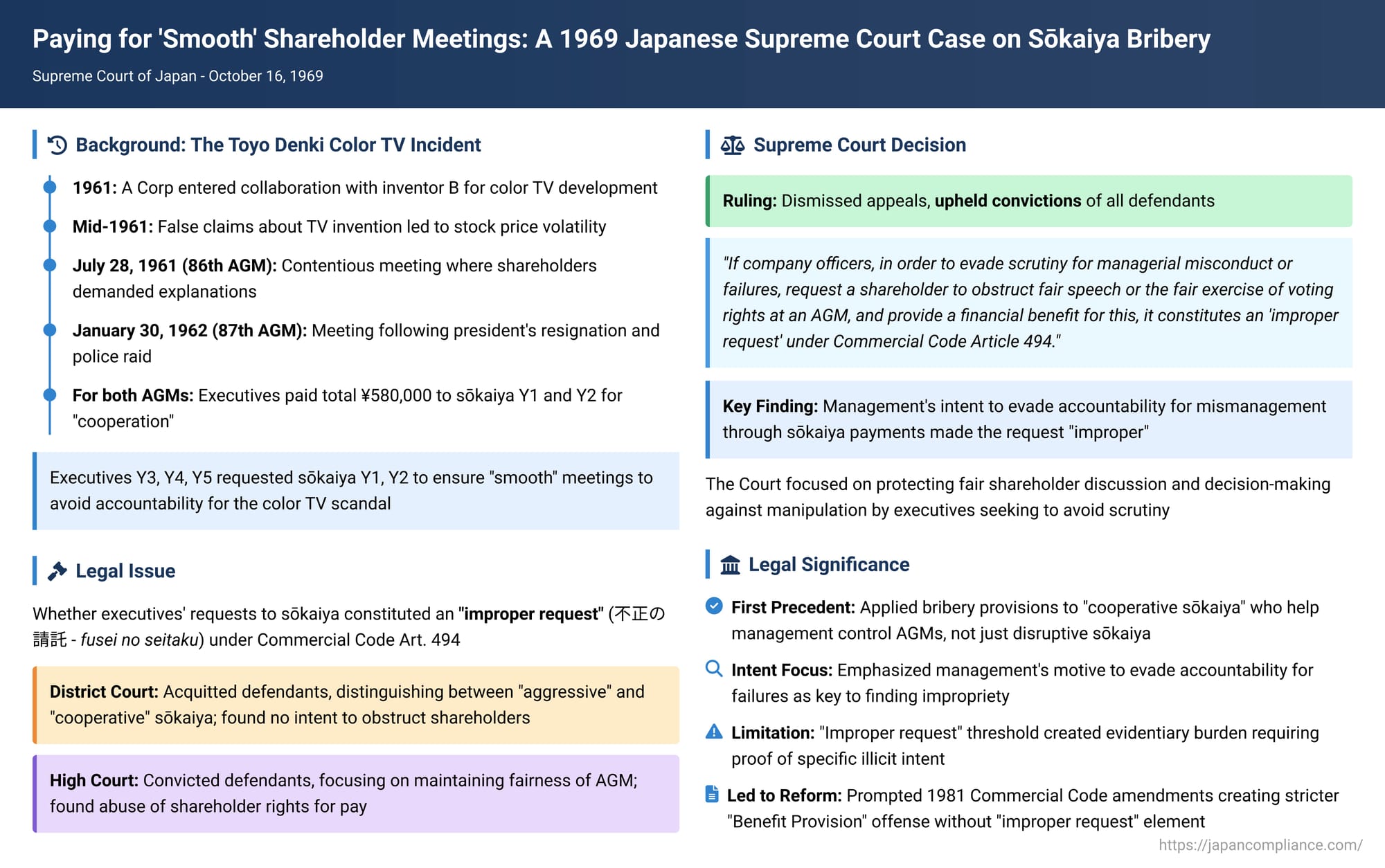

For many years, Japanese corporate annual general meetings (AGMs) were often plagued by the presence of sōkaiya – individuals or groups who specialized in disrupting or, conversely, ensuring the smooth passage of shareholder meetings, typically for a fee. A landmark 1969 Supreme Court of Japan decision, arising from what became known as the "Toyo Denki Color TV Incident," addressed the criminal liability of corporate executives who paid sōkaiya to control AGMs, particularly when management sought to avoid scrutiny for its own failings. This case was pivotal in interpreting the scope of bribery provisions under the then-Commercial Code concerning the exercise of shareholder rights.

The Corporate Scandal and the Tumultuous AGMs

The backdrop to this case was a significant corporate scandal involving A Corp.

- The Color TV Venture: Around January 1961, A Corp entered into a technical collaboration agreement with an inventor, B, concerning color television patents, investing heavily in B's research. By April 1961, B falsely reported the completion of a new color TV model, which was, in reality, merely a modified version of another company's product. A Corp's top executives, including its president, viewed this supposed invention in early May.

- Stock Market Speculation: From February 1961, rumors about A Corp's color TV development fueled a speculative surge in its stock price, which rose from under ¥150 to ¥353 by early March. The Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) intervened, imposing price limits and later designating A Corp's stock as a "reporting stock" requiring closer scrutiny. Despite repeated inquiries from the TSE, A Corp consistently denied any actual research or completion of a color TV, keeping the matter officially secret. However, market rumors persisted, causing wild fluctuations in the stock price.

- Public Announcement and Subsequent Fallout: Pressured by B to publicize the "invention," A Corp eventually made a public announcement to the TSE and press club on June 20, 1961, followed by a demonstration for the media on June 28, where B again made false claims about the product's performance. A Corp's stock price initially soared again, from ¥369 to ¥505 by early July. However, media reports soon began to highlight inconsistencies in B's explanations and raised doubts about the invention's authenticity, causing the stock price to plummet. When A Corp sought technical clarifications from B, B failed to comply. By October 31, A Corp terminated its contract with B, and on November 28, A Corp's president resigned, taking responsibility for the debacle.

This turmoil directly impacted A Corp's shareholder meetings:

- The 86th AGM (July 28, 1961): This meeting was highly contentious, with shareholders demanding explanations regarding the color TV development. To manage the proceedings, A Corp's management enlisted the "cooperation" of Y2, a sōkaiya operating under the umbrella of a more prominent sōkaiya, Y1. Through Y2's aggressive efforts in controlling the flow of the meeting, the company managed to get all its proposed agenda items approved as planned. A subsequent explanatory session also descended into chaos and was abruptly concluded, citing the venue's rental time limit.

- The 87th AGM (January 30, 1962): This meeting was anticipated to be even more challenging. The president had resigned over the color TV scandal, and just days before, on January 20, police had raided A Corp's offices and the homes of its directors in connection with suspected securities law violations by the inventor B. However, this meeting concluded surprisingly quickly. This was attributed to a police presence ensuring venue security and, crucially, the "cooperation" of Y1, Y2, and an executive of an organized crime group, C (who had been requested by Y1 to attend and assist in managing the proceedings).

The Alleged Bribery

The prosecution's case centered on payments made by A Corp executives to the sōkaiya. It was established that prior to both AGMs, senior executives of A Corp – Y3 (Vice President), Y4 (Managing Director), and Y5 (Director) – had met with and entertained Y1 and Y2 at establishments like high-end restaurants. During these meetings, the executives requested the "coordination and cooperation" of Y1 and Y2 in managing the upcoming AGMs to ensure they proceeded smoothly according to management's plans. Y1 and Y2 agreed to provide this "service."

Following each AGM, Y3, Y4, and Y5 arranged for payments totaling ¥580,000 to be made to Y1 and Y2 as "gratuities" or "rewards" for their efforts. These payments led to the indictment of Y1, Y2, Y3, Y4, and Y5 for violating Article 494, Paragraphs 1(i) and 2 of the then-Commercial Code (corresponding to Article 968 of the current Companies Act). This article criminalized the giving or receiving of property or financial benefits based on an "improper request" (不正の請託 - fusei no seitaku) concerning speaking or exercising voting rights at a shareholders' meeting.

The Legal Question: "Improper Request" and Sōkaiya Activity

The core legal issue was whether the request made by A Corp's executives to the sōkaiya for their "cooperation" in managing the AGMs constituted an "improper request" under the Commercial Code.

- The Court of First Instance (Tokyo District Court) acquitted the defendants. It drew a distinction between two types of sōkaiya:

- "Aggressive sōkaiya" or "meeting disruptors" (sōkai arashi - 総会荒し), who extort companies by threatening to disrupt AGMs or who actually do so to obstruct other shareholders.

- "Cooperative sōkaiya," who, for a fee, assist company management in ensuring AGMs run smoothly and company proposals are passed.

The District Court reasoned that Article 494 was primarily intended to punish the former category – those who obstruct the rights of other shareholders. It found no evidence that A Corp's executives had asked Y1 and Y2 to unlawfully obstruct other shareholders; rather, they had requested assistance in facilitating the company's agenda. Thus, it concluded, this did not amount to an "improper request."

- The Appellate Court (Tokyo High Court) reversed this decision and found the defendants guilty. It held that Article 494's purpose was to maintain the safety and fairness of the exercise of rights at AGMs. Therefore, it applied to anyone, regardless of whether they were labeled "disruptors" or "cooperative sōkaiya," who received or gave benefits for a request to abuse shareholder rights. This included requests to disrupt other shareholders' legitimate exercise of rights or to improperly refrain from exercising one's own rights for pay.

The defendants appealed their convictions to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Upholding Convictions

The Supreme Court, in its decision dated October 16, 1969, dismissed the appeals, thereby upholding the guilty verdicts. The Court's reasoning focused on the definition of an "improper request" in the context of management seeking to evade accountability:

- Company's Distinct Interest and Fair AGMs: The Court began by stating that while shareholders hold shares for their individual benefit, a stock company (kabushiki kaisha) is a distinct legal entity with its own interests separate from those of its individual shareholders. To protect these corporate interests from being infringed, it is essential that discussions at AGMs are conducted fairly and that resolutions are passed fairly.

- Defining "Improper Request": The Court then addressed the core issue:

"Therefore, if company officers, in order to evade scrutiny for managerial misconduct or failures, request a shareholder to obstruct fair speech or the fair exercise of voting rights at an AGM, and provide a financial benefit for this, it constitutes an 'improper request' under Commercial Code Article 494." - Application to the Facts: Applying this principle, the Supreme Court found that in this specific case:

- A Corp's officers were facing the likelihood of being held accountable by shareholders at the upcoming AGMs for their significant mismanagement and failures related to the color TV development.

- In this context, their request to the sōkaiya (who were either shareholders themselves or acting as proxies) to receive remuneration for suppressing the comments of other general shareholders and for maneuvering the meeting's proceedings to ensure the company's original agenda was passed, amounted to an "improper request" under the statute.

The Supreme Court thus found the High Court's judgment convicting the defendants to be appropriate.

Unpacking "Improper Request" (Fusei no Seitaku)

The term "improper request" was a key element in Article 494 of the old Commercial Code. It was added during the legislative process that created the anti-sōkaiya bribery provision in 1938, reflecting a concern that criminalizing all payments related to the exercise of shareholder rights (which are private rights) might be excessive. However, this requirement made the statute more difficult to apply broadly against sōkaiya.

An "improper request" generally means a request concerning the exercise or non-exercise of rights that is itself unlawful or grossly unreasonable. It's not merely about influencing a shareholder's vote with money, but about doing so when the requested action crosses the boundary of legitimate rights exercise, such as when it is intended solely to harm other shareholders or to achieve an illicit objective. Classic examples include requests to obstruct other shareholders through violence, intimidation, or deceit, or requests to exercise/not exercise rights solely to facilitate an unlawful corporate act.

Analysis and Implications

The 1969 "Toyo Denki Color TV Incident" decision was highly significant:

- Application to "Cooperative Sōkaiya": It was the first Supreme Court ruling to clearly affirm that payments made by company management to "cooperative sōkaiya" – those who work with management to control AGMs – could constitute criminal bribery. This rejected the narrower view that the law only targeted overtly "disruptive" sōkaiya. The Court implicitly recognized that collusion between management and sōkaiya to stifle legitimate shareholder discourse could be just as damaging to corporate governance as overt disruption.

- Focus on Management's Illicit Intent: The Supreme Court's interpretation of "improper request" hinged on the motive of the company executives making the request. The impropriety arose because the executives sought the sōkaiya's help to evade accountability for their own managerial failures. This suggests that not all payments to individuals for assisting with AGM proceedings would automatically be criminal. For instance, a request for assistance in maintaining order through lawful means, or for using permissible parliamentary tactics to counter genuinely disruptive shareholders (without suppressing legitimate debate about management performance), might not have met the "improper request" threshold if the underlying purpose was not to shield managerial wrongdoing.

- Limitations of the "Improper Request" Threshold: While this decision expanded the potential reach of Article 494, the "improper request" element still posed a hurdle for prosecutors. Proving the specific illicit intent of management could be challenging. Legal commentators have noted that this relatively narrow interpretation of "improper request" (requiring proof of management's intent to evade accountability for specific misconduct) limited the overall effectiveness of Article 494 as a comprehensive tool against the broader phenomenon of sōkaiya influence.

- Paving the Way for Stricter Legislation: The perceived limitations of Article 494, even after this Supreme Court decision, contributed to legislative reforms. In 1981, the Commercial Code was amended to introduce a much stricter provision (Article 497, now Article 970 of the Companies Act) prohibiting companies from giving, and anyone from receiving, any property benefit "on account of the company" in relation to the exercise of shareholder rights. This new offense of "Benefit Provision" (rieki kyōyo zai) does not require proof of an "improper request," making it a far more potent weapon against all forms of sōkaiya activity and illicit payments designed to influence shareholder rights, regardless of the specific subjective intent behind a "request."

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1969 decision in the Toyo Denki case was a critical step in Japan's long battle against the detrimental influence of sōkaiya on corporate governance. It established that paying individuals to manage shareholder meetings in a way that shields management from accountability for its failures constitutes criminal bribery due to the "improper request" involved. While this ruling was significant for extending liability to "cooperative sōkaiya," its reliance on proving management's specific illicit purpose highlighted the limitations of the existing law, ultimately contributing to the enactment of more comprehensive anti-sōkaiya legislation. The case remains a key illustration of the judiciary's efforts to ensure the fairness and integrity of shareholder meetings.