Paying for Silence: Corporate Raider Threats and Illegal Shareholder Payments in Japan

Corporate governance can be severely tested when companies face aggressive corporate raiders or disruptive shareholders. In such high-stakes environments, management might be tempted to make payments or provide other benefits to neutralize perceived threats. However, Japanese company law strictly prohibits providing benefits to shareholders "in connection with the exercise of shareholder rights" (a practice known as riekikyōyo). A Japanese Supreme Court decision on April 10, 2006, provided a crucial interpretation of this prohibition, particularly in the context of payments made to prevent "undesirable" shareholders from exercising their influence.

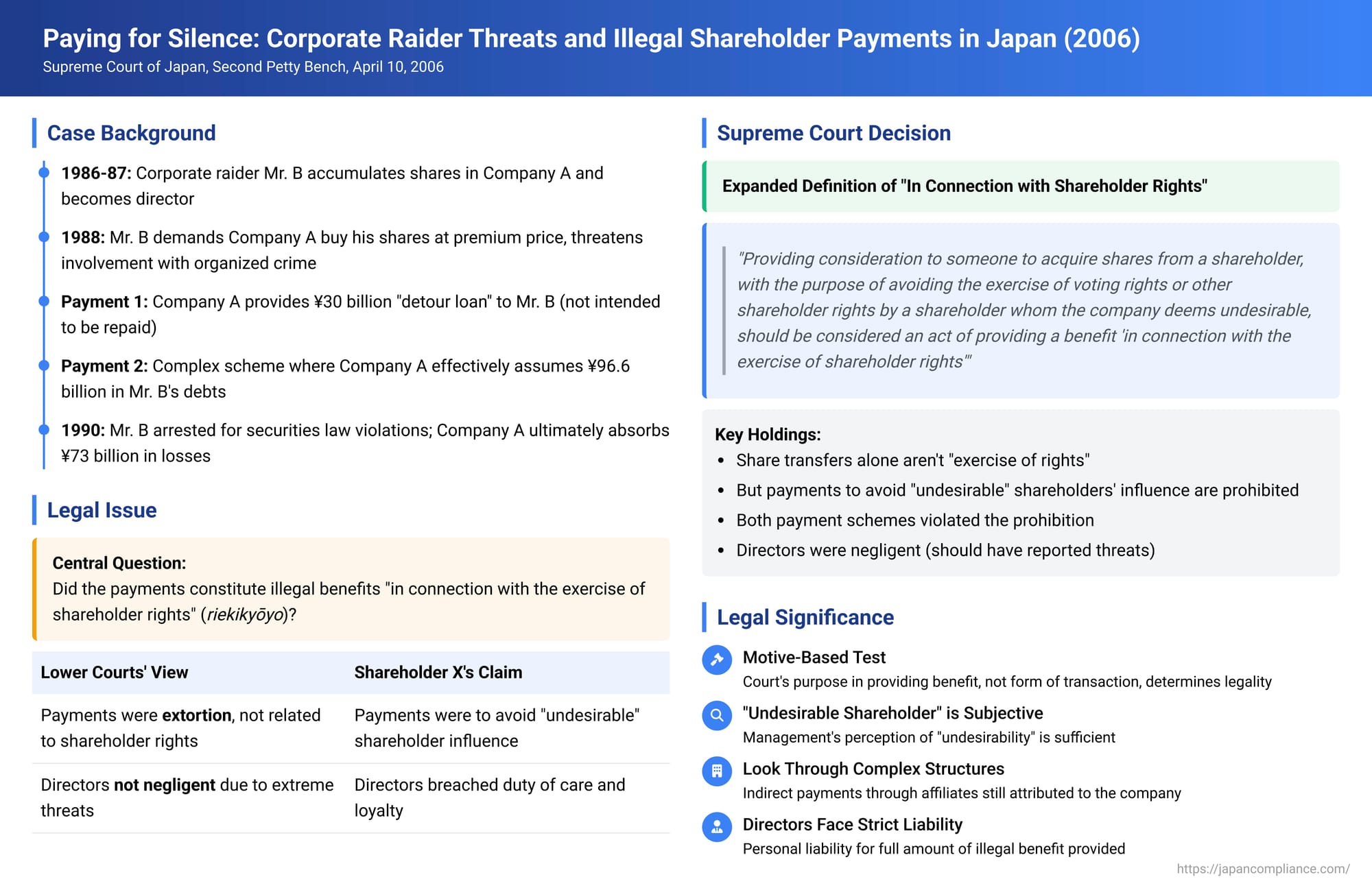

The Facts: A Notorious Corporate Raider's Campaign

The case involved Company A, a publicly traded company listed on the First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange. Starting around 1986, Mr. B, a figure well-known as a corporate raider (shite-suji), began accumulating a significant stake in Company A through companies he controlled. By June 1987, he had become a director of Company A.

From approximately October 1988, Mr. B started pressuring Company A's representative directors, Y1 and Y2, to buy out his substantial shareholding at a premium price. When Company A initially resisted these demands, Mr. B escalated his tactics. He insinuated that he had already sold his Company A shares to a company affiliated with organized crime (暴力団 - bōryokudan) and demanded a staggering 30 billion yen to "cancel" this purported sale. He further threatened Director Y2 and another Company A director, Y3, by ominously stating that "two hitmen have come from Osaka."

Faced with these threats, Company A's board of directors, with the unanimous consent of all directors then present or subsequently agreeing (including Y1, Y2, Y3, and two other directors, Y4 and Y5 – collectively "Directors Y1-Y5"), decided to address Mr. B's demand. This led to two major series of transactions:

- The 30 Billion Yen "Detour Loan": Company A arranged for 30 billion yen to be provided to Mr. B. This was structured as a "detour loan" (ukai yūshi), funneled through an intermediary company. The court later found that Mr. B had no intention of repaying this sum, and there was no realistic prospect of Company A ever recovering it.

- The 96.6 Billion Yen Debt Assumption Scheme: Even after receiving the 30 billion yen, Mr. B continued to pressure Company A and its main financial institution, E Bank. He demanded that they take over approximately 96.6 billion yen in debts that his (Mr. B's) companies had incurred in the process of acquiring shares in Company A and other entities. In response, Directors Y1-Y5 orchestrated a complex scheme. An affiliated company of Company A would obtain loans from Mr. B's original creditors. This loan money would then be lent by Company A's affiliate to Mr. B's companies, with Mr. B's Company A shares pledged as collateral. Mr. B's companies would then use these funds to pay off their debts to their original creditors. This effectively amounted to Company A, through its affiliate, assuming Mr. B's companies' massive debts. As part of this arrangement, Company A itself placed mortgages on its own real estate to secure a portion (39 billion yen) of these obligations. The valuation of Mr. B's Company A shares used as collateral was based on an artificially inflated price of 5,000 yen per share, a price allegedly achieved through share price manipulation. Furthermore, Company A's affiliated company lacked the independent financial capacity to service or repay the enormous debt it had taken on, meaning that if the affiliate defaulted, Company A would inevitably have to bear the ultimate financial burden.

In July 1990, Mr. B was arrested on suspicion of violating securities laws and subsequently resigned from Company A's board. Later, through various settlements and workout arrangements, Company A ultimately absorbed the 30 billion yen from the detour loan and an additional 43 billion yen related to the assumed debts.

Shareholder X, a former director of Company A and its affiliated companies and also a current shareholder of Company A, filed a derivative lawsuit against Directors Y1-Y5. X alleged that their involvement in the 30 billion yen payment and the debt assumption scheme constituted a breach of their duty of loyalty and duty of care to Company A, causing the company substantial damages (then under Commercial Code Article 266, Paragraph 1, Item 5). During the proceedings, Shareholder X also added a claim that these actions constituted illegal payments to a shareholder in connection with the exercise of shareholder rights (riekikyōyo), invoking directors' liability under then Commercial Code Article 266, Paragraph 1, Item 2 (which cross-referenced the prohibition in Article 294-2, the precursor to Article 120 of the current Companies Act).

Lower Courts: Excusing Directors Amidst Threats

Both the Tokyo District Court (first instance) and the Tokyo High Court (appellate instance) dismissed Shareholder X's claims.

- Regarding the breach of duty of loyalty and care, while both courts acknowledged that the payments and debt assumption appeared to be violations, they ultimately found that the directors were not negligent. This conclusion was based on the extreme pressure and threats exerted by Mr. B, leading the directors to believe they were acting to prevent even greater harm to Company A (such as a takeover or severe disruption by organized crime elements).

- Regarding the claim of illegal payments (riekikyōyo), the lower courts held:

- The 30 billion yen payment was perceived by Company A's management as a payment to Mr. B to enable him to "retrieve" shares supposedly sold to an organized crime affiliate. In reality, the courts saw it as money extorted from the company, rather than a payment made "in connection with the exercise of shareholder rights."

- The debt assumption and collateral provisions were characterized by the High Court as merely a loan and collateral provision by Company A to its own affiliated company, and therefore not a payment made to a shareholder "in connection with the exercise of shareholder rights."

Shareholder X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Interpretation of "Illegal Payments" (Rieki Kyōyo)

The Supreme Court, in its Second Petty Bench judgment, reversed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings (primarily on damages). The Supreme Court's key findings concerned the interpretation of "in connection with the exercise of shareholder rights" for the purpose of the riekikyōyo prohibition.

1. The General Principle Regarding Share Transfers:

The Court first stated a general principle: "The transfer of shares is a transfer of shareholder status and, in itself, does not constitute an 'exercise of shareholder rights.' Therefore, even if a company provides a benefit to someone as consideration for transferring shares, this does not automatically fall under the prohibition of providing benefits under [then] Commercial Code Article 294-2, Paragraph 1."

2. The Crucial Exception: When Purpose Matters:

However, the Supreme Court immediately carved out a critical exception:

"Nevertheless, an act of providing consideration to someone to acquire shares from a shareholder, with the purpose of avoiding the exercise of voting rights or other shareholder rights by a shareholder whom the company deems undesirable, should be considered an act of providing a benefit 'in connection with the exercise of shareholder rights' as stipulated in the said provision."

3. Application to the 30 Billion Yen Payment:

Applying this principle to the 30 billion yen "detour loan," the Supreme Court found:

- Company A made this payment because it believed Mr. B's assertion that he had sold his substantial block of Company A shares to an organized crime affiliate.

- Company A feared that individuals connected to organized crime would become major shareholders and interfere with its management and operations.

- The payment of approximately 30 billion yen—an "utterly unjustifiable enormous sum"—was made to Mr. B (via the detour loan structure) for the specific purpose of enabling Company A to (indirectly) "buy back" those shares and thereby avoid this feared interference and exercise of rights by undesirable new shareholders.

- Therefore, the Court concluded, this provision of benefit by Company A was made "in connection with the exercise of shareholder rights" and thus fell within the scope of the riekikyōyo prohibition.

4. Application to the Debt Assumption Scheme (the "Countermeasure"):

The Supreme Court applied similar reasoning to the complex debt assumption and collateral provision scheme:

- Although an affiliated company of Company A was formally the entity taking on loans and lending to Mr. B's companies, Company A itself and its wholly-owned subsidiary provided substantial real estate as collateral.

- Moreover, there was an underlying premise that if the affiliated company became unable to pay, Company A would ultimately have to assume responsibility for the debt.

- Thus, the substance of this scheme was a massive provision of financial benefits by Company A, albeit indirectly through its affiliates.

- This "Countermeasure" was adopted in a context where Mr. B was threatening to sell his Company A shares to E Bank or other parties. The purpose of this scheme was "to preemptively block future acquirers of Mr. B's shares from exercising their rights as shareholders, and concurrently, to neutralize Mr. B's influence as a major shareholder."

- Consequently, the Supreme Court held that the debt assumption and collateral provision under this scheme also constituted benefits provided "in connection with the exercise of shareholder rights."

The Supreme Court also found that the directors were negligent in their handling of these matters, particularly in yielding to Mr. B's demands without taking appropriate countermeasures such as reporting the threats to the police. It determined that the circumstances were not such that the directors could not have been expected to take such proper actions. This finding of negligence was crucial for the breach of duty of care claim.

Defining "In Connection with the Exercise of Shareholder Rights"

This Supreme Court decision significantly clarified the meaning of the phrase "in connection with the exercise of shareholder rights" for the purpose of the riekikyōyo prohibition (now Companies Act Article 120).

- Historical Context: The riekikyōyo regulation was introduced into the Commercial Code in 1981. A primary target of this legislation was the practice of companies making payments to sōkaiya—individuals who would acquire a small number of shares and then threaten to disrupt annual shareholder meetings with lengthy or irrelevant questions, or who would offer to ensure smooth meetings, all for a payoff. Such payments were often made to prevent these sōkaiya from exercising their shareholder rights (like the right to speak or ask questions) in an obstructive manner, or to induce them to sell their shares and disappear. The law was drafted broadly to prohibit providing benefits to "any person" in this context, not just registered shareholders.

- The Motive-Based Test: The Supreme Court, in this 2006 decision, endorsed a motive-based test. While the mere act of a company facilitating a share transfer or even buying its own shares (where legally permitted) might not automatically be riekikyōyo, it becomes so if the company's purpose in providing the financial benefit is to influence or prevent the exercise of shareholder rights, particularly by those it deems "undesirable." The PDF commentary notes that this aligns with an earlier Tokyo District Court decision (Heisei 7.12.27) but acknowledges the potential difficulty in proving such a motive. However, the commentary also suggests the Supreme Court might consider this illicit purpose to be relatively easy to infer in many such cases.

- Who is an "Undesirable Shareholder"?: The Court used the phrase "shareholder judged undesirable from the company's perspective" (会社から見て好ましくないと判断される株主). The PDF commentary suggests that, for the purpose of determining if a payment is riekikyōyo, this criterion likely refers to the subjective judgment of the person providing the benefit (i.e., the company's management). There is no requirement that the shareholder be objectively determined as "undesirable" by, for example, a majority vote of other shareholders. Indeed, in this case, even a major financial institution like E Bank was considered a potentially "undesirable" acquiring party from the perspective of Company A's management trying to avoid Mr. B selling his shares to them.

Attributing the Act of Payment to the Company

The Supreme Court also made it clear that the prohibition on illegal payments can apply even if the benefit is channeled through affiliated companies. If the parent company provides collateral, bears the ultimate financial risk, or effectively orchestrates the scheme, the act can be attributed to the parent company as the entity providing the illegal benefit. This principle of looking at the substance ("who's calculation" or 実質的に会社の計算 - jisshitsuteki ni kaisha no keisan) was later explicitly reflected in Commercial Code amendments.

Implications for Directors' Liability

This judgment broadens the circumstances under which payments related to share transactions can be classified as illegal riekikyōyo. Directors who authorize or participate in such schemes face significant personal liability to the company for the amount of the illegal benefit provided.

- Under the Companies Act (Article 120, Paragraph 4), directors who are involved in providing illegal benefits are liable to the company. For directors who were not directly responsible for the act of providing the benefit but who consented to it (e.g., by voting for it at a board meeting), their liability is now fault-based, but with a reversed burden of proof: they are liable unless they can prove they were not negligent in performing their duties. The person who actually received the benefit is also liable to return it.

- It suggests that the Supreme Court's interpretation of "in connection with the exercise of shareholder rights" in this 2006 case will likely continue to apply under the current Companies Act. The shift to a rebuttable negligence standard for some directors might influence how broadly the "exercise of rights" element is construed, but the core motive-based test established here remains fundamental.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's April 10, 2006, decision in this high-profile case involving a corporate raider delivered a strong message regarding the prohibition on illegal payments to shareholders. It clarified that financial benefits provided by a company, even indirectly, with the aim of preventing certain shareholders (or potential transferees) from exercising their rights—such as voting or otherwise influencing management—fall squarely within the definition of payments made "in connection with the exercise of shareholder rights." This ruling underscores the importance of the underlying purpose behind such transactions and serves as a stark reminder to corporate directors of their duties to the company and the significant personal liability they face if they engage in or approve such prohibited payments, regardless of the pressures they might face from aggressive market participants.