Paycheck vs. Payback: Japan's Nisshin Steel Case on Consensual Set-Offs Against Wages

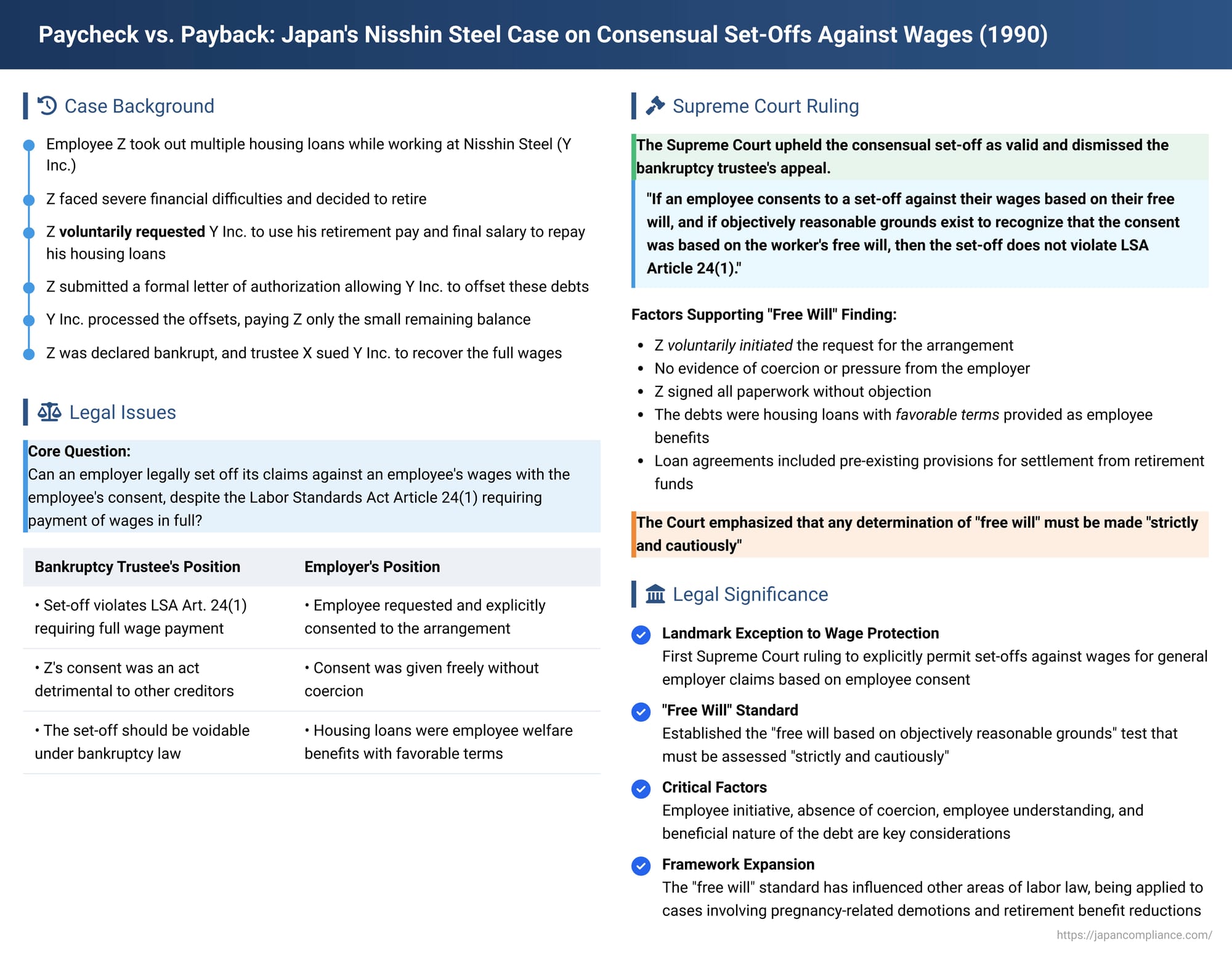

The principle of full payment of wages, enshrined in Article 24, Paragraph 1 of Japan's Labor Standards Act (LSA), is a fundamental protection for workers. It mandates that employers must pay wages in their entirety directly to the employee, in cash (with limited exceptions for bank transfers with consent), and at least once a month on a fixed date. This rule aims to ensure that workers reliably receive their earnings, which are crucial for their economic livelihood, thereby preventing employers from unilaterally making deductions. Generally, this principle has been interpreted by the Supreme Court to prohibit employers from setting off their own claims against an employee's wage claims. However, the Supreme Court case of Nisshin Seiko (Nisshin Steel Co., Ltd.), decided on November 26, 1990, carved out a significant exception: such set-offs are permissible if the employee consents to the arrangement based on their genuine and informed free will, under specific, carefully scrutinized conditions.

The Nisshin Steel Dilemma: Housing Loans, Bankruptcy, and Retirement Pay

The case involved Mr. Z, an employee of Y Inc. (Nisshin Steel Co., Ltd.). During his employment, Z had taken out several housing loans: one directly from Y Inc., another from S Bank (facilitated by Y Inc.), and a third from H Labor Credit Association (H LCA). These loan agreements commonly included provisions for lump-sum repayment of any outstanding balance from Z's retirement benefits should he leave the company.

Mr. Z later fell into severe financial difficulties, accumulating substantial debts from various sources, and eventually faced a situation where bankruptcy seemed inevitable. He decided to retire from Y Inc. and approached the company with a request: he wanted Y Inc. to handle the repayment of his outstanding balances on the aforementioned housing loans using his accrued retirement pay and final salary. To formalize this, Z submitted a letter of authorization ("the Current Letter of Authorization") to Y Inc. In this document, he explicitly stated that he had no objection to the company using all his financial claims against Y Inc. (retirement pay, salary, etc.) to settle his debts to Y Inc. (for the direct housing loan) and to the H Labor Credit Association upon his retirement.

Y Inc. accepted Z's resignation. It then proceeded with what was termed "the Current Settlement Process": Y Inc. offset its own direct loan to Z, as well as its claims for reimbursement of advance payments it would make to S Bank and H LCA on Z's behalf (under Article 649 of the Civil Code, for fulfilling Z's mandate to repay these institutions), against Z's retirement pay and final salary entitlement. Only the small remaining balance was paid directly to Z.

Shortly thereafter, Z was formally declared bankrupt. Mr. X was appointed as the bankruptcy trustee. X then sued Y Inc., seeking to recover the full amount of Z's retirement pay and salary that had been offset. The trustee's primary arguments were that the settlement process (the set-off) violated the full wage payment principle of LSA Article 24(1) and that Z's consent to this set-off constituted an act detrimental to other bankruptcy creditors and was therefore voidable by the trustee under bankruptcy law.

The Osaka District Court found the settlement process itself valid but allowed the trustee's avoidance claim. However, the Osaka High Court held that the settlement process was valid and that it was not subject to the bankruptcy trustee's avoidance powers, thereby ruling in favor of Y Inc.. The bankruptcy trustee, X, appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's 1990 Ruling: Upholding Consensual Set-Off

The Supreme Court dismissed the trustee's appeal, affirming the High Court's decision and thus upholding the validity of the set-off. The Court's reasoning provided a critical clarification on the application of LSA Article 24(1) in cases of consensual set-offs.

- Reaffirming the Intent of the Full Wage Payment Principle: The Court began by acknowledging that the core purpose of LSA Article 24(1) is to prohibit employers from unilaterally deducting amounts from an employee's wages. This ensures that workers receive the entirety of their earned wages, thereby protecting their economic stability. This general principle, the Court reiterated, encompasses a prohibition against employers setting off their own claims against an employee's wage claims.

- The Crucial Exception: Set-Off with Employee's Free-Will Consent: However, the Supreme Court introduced a significant qualification. It held that if an employee consents to such a set-off against their wages, and this consent is given based on their "free will," then the set-off does not violate LSA Article 24(1), provided that "objectively reasonable grounds exist to recognize that the said consent was based on the worker's free will". In making this point, the Court referenced its earlier decision in the Singer Sewing Machine case, which had established a similar "free will" standard for the validity of an employee's waiver of wage claims.

- "Strict and Cautious" Assessment of Free Will: The Court emphasized that any determination regarding whether an employee's consent was truly based on their free will must be made "strictly and cautiously".

- Application to Z's Consent: Applying this standard to the facts of the Nisshin Steel case, the Supreme Court found that Z's consent was indeed genuinely voluntary and met the required criteria:

- Z had voluntarily initiated the request for Y Inc. to manage the repayment of his specific housing loans from his retirement funds.

- There was no evidence suggesting any form of coercion or undue pressure by Y Inc. in the process of Z preparing and submitting the letter of authorization.

- After the settlement process was completed, Z, when presented with the details and asked to sign related paperwork (retirement pay calculation, salary receipts), did so without objection.

- The nature of the debts being offset was significant: they were housing loans, generally considered beneficial to the employee, provided at low interest rates with long repayment periods. In fact, Y Inc. had subsidized a portion of the interest on some of these loans as an employee welfare measure.

- Z was fully aware of the loan agreements, including the pre-existing stipulations that the outstanding balances would be settled from his retirement funds if he left the company.

Based on these cumulative factors, the Supreme Court concluded that "objectively reasonable grounds existed to recognize that Z's consent to the Current Set-off was based on his free will". The Court also found that, under these circumstances, the set-off was not an act that could be avoided by the bankruptcy trustee.

The "Free Will" Standard and Its Foundations

The Nisshin Steel decision was significant as it was the first Supreme Court ruling to explicitly permit set-offs against wages for general employer claims (beyond mere technical adjustments for overpayments) based on employee consent. Before this case, the Supreme Court had strictly interpreted LSA Article 24(1) as generally prohibiting such set-offs. While an exception for "adjustment set-offs" for wage overpayments under very specific conditions had been recognized (as in the Fukushima Prefecture Teachers Union case), and the validity of an employee's waiver of wage claims based on "free will" had also been affirmed (Singer Sewing Machine case), Nisshin Steel directly addressed consensual set-offs for pre-existing debts.

The ruling effectively endorsed the "free will theory" over a "uniform invalidity theory" for consensual wage set-offs. A judicial clerk's commentary on the case suggested that the rationale included the absence of substantial harm to the worker when consent is freely given, and, pertinent to this specific case, Z's bankruptcy meant that disallowing the set-off could unfairly cause Y Inc. to suffer a double loss (the unpaid loan and potentially having to pay the full retirement sum to the trustee). However, it was also noted that the judgment itself did not provide extensive reasoning for how the mandatory nature of LSA Article 24(1) could be bypassed solely by employee consent.

This aspect has drawn criticism from some legal scholars who emphasize the strong protective and mandatory character of LSA Article 24(1), arguing that the explicit provision for exceptions via labor-management agreements should be the primary route for any deviation. Others have sought to interpret the Nisshin Steel ruling narrowly, suggesting it applies only to specific contexts where the set-off might not be seen as directly prohibited, or by closely aligning its logic with that of employee wage waivers.

Factors Influencing the "Free Will" Assessment

While the Nisshin Steel judgment mandated a "strict and cautious" determination of free will, it did not lay down an exhaustive list of general criteria. However, its application of the standard in Z's case highlighted several important considerations:

- Employee Initiative: Whether the employee themselves proposed or voluntarily requested the arrangement.

- Absence of Coercion: The lack of any pressure or undue influence from the employer.

- Employee's Understanding: The employee's full awareness of the transaction, its implications, and the underlying agreements.

- Nature of the Debt: The characteristics of the debt being offset are crucial. In this case, they were beneficial housing loans with pre-existing agreements for repayment from retirement funds. Unlike a pure wage waiver, where the employee receives no direct reciprocal benefit, a set-off against a genuine debt results in the employee's liability being reduced, which is a tangible benefit.

The judgment did not explicitly clarify whether a finding that consent was not based on free will would mean the consent itself never legally formed or simply that its effect is nullified. However, from a practical standpoint, if free will is absent, the set-off would violate LSA Article 24(1).

Scope and Limitations of the Nisshin Seiko Principle

The principles established in Nisshin Steel are generally understood to apply not only to ad-hoc employee consent to a set-off proposed by the employer but also to more formal set-off agreements entered into by both parties.

It is important to distinguish this from the prohibition found in LSA Article 17, which forbids employers from setting off against wages any "advances" or loans made on the condition that the employee will work to repay them. LSA Article 17 is aimed at preventing forced labor and situations where employees become bound to an employer due to debt. The housing loans in the Nisshin Steel case, being for employee welfare and not directly conditioned on continued labor in a way that restricts resignation, were not considered to fall under the LSA Article 17 prohibition. Therefore, the "free will" exception established in Nisshin Steel for LSA Article 24(1) does not automatically extend to override the specific prohibitions of LSA Article 17.

Influence on Other Areas of Labor Law ("Framework Transposition")

Despite the criticisms and calls for a narrow interpretation, the "free will based on objectively reasonable grounds" framework, as articulated in Nisshin Steel and the earlier Singer Sewing Machine case, has proven to be influential. While its direct application to other contexts was initially limited, recent years have seen the Supreme Court apply similar reasoning to different labor law issues:

- In the Hiroshima Chuo Health Co-operative Society case, concerning the prohibition of disadvantageous treatment related to pregnancy-related requests for lighter duties, the Court recognized an exception if "objectively reasonable grounds exist to recognize that the said worker consented to the demotion based on her free will".

- In the Yamanashi Kenmin Shinyo Kumiai case, dealing with the binding force of work rule changes that reduced retirement benefits, where employees had signed consent forms, the Court stated that the validity of such consent should be judged from the perspective of "whether objectively reasonable grounds exist to recognize that the said act of acceptance... was based on the worker's free will".

These later cases, while involving measures that led to wage reductions and thus touching upon the spirit of LSA Article 24(1), directly concerned different primary legal norms (the Equal Employment Opportunity Act and Articles 8 & 9 of the Labor Contract Act, respectively). This suggests a potential expansion of the "free will based on objectively reasonable grounds" test as a general standard for evaluating the validity of employee consent in various situations involving potentially disadvantageous changes to employment terms. The future scope of this "framework transposition" remains an area of keen interest in Japanese labor law.

Conclusion

The Nisshin Steel Supreme Court decision of 1990 established a significant, albeit carefully circumscribed, exception to the LSA's full wage payment principle. It affirmed that an employer may, without violating LSA Article 24(1), set off its claims against an employee's wages if the employee has consented to this arrangement based on their genuine and informed free will, a determination that courts must make "strictly and cautiously." The ruling emphasized the importance of the employee's voluntary initiative, the absence of employer coercion, the employee's understanding of the agreement, and the nature of the underlying debt. While subject to ongoing academic debate regarding its precise theoretical underpinnings and scope, the Nisshin Steel "free will" standard has become a crucial reference point in Japanese labor law, influencing not only how consensual wage deductions are viewed but also potentially shaping the assessment of employee consent in a broader range of employment contexts.