Payback Time? Japanese Supreme Court on Good Faith Limits to Reclaiming Unauthorized Director Severance

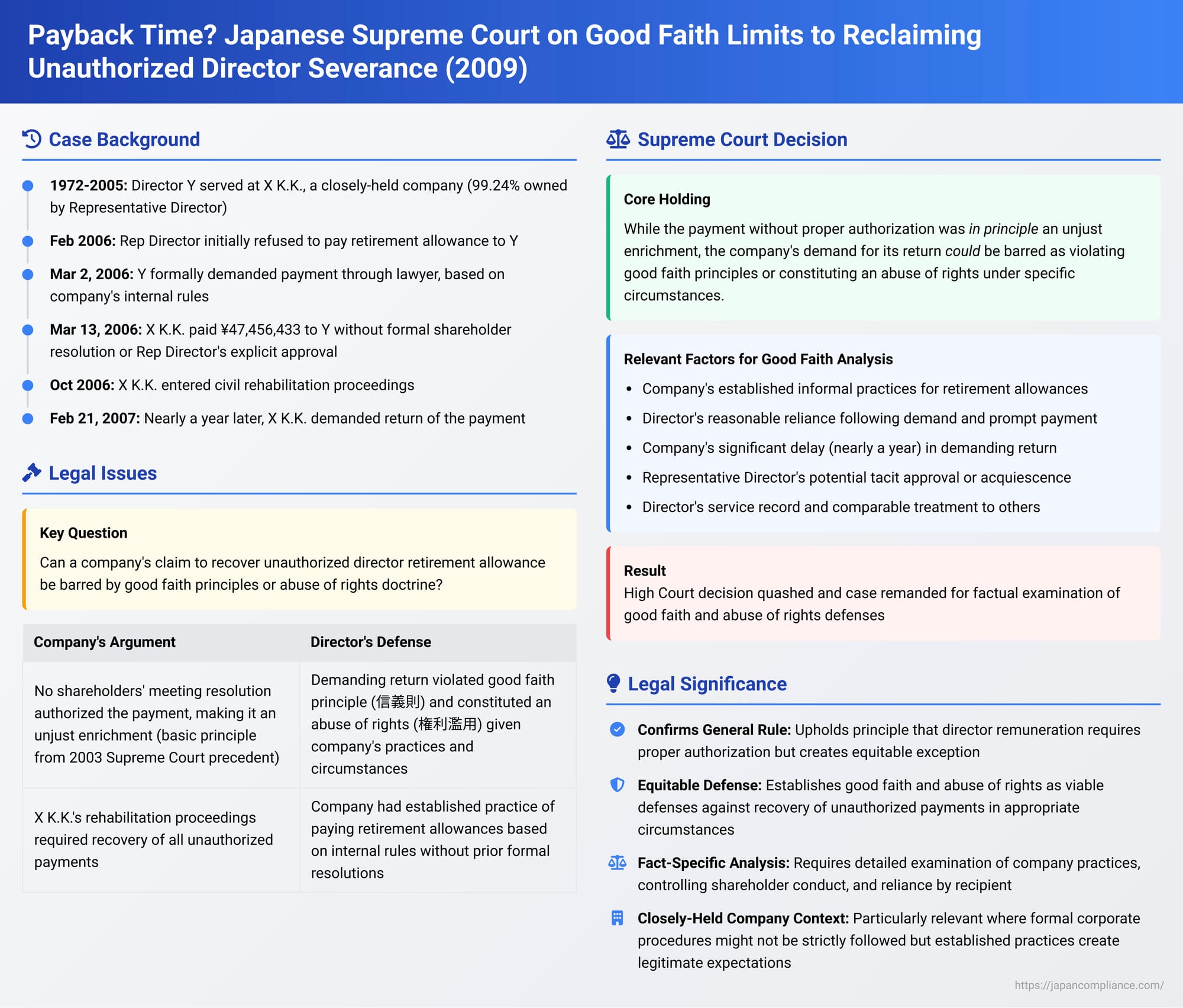

Date of Judgment: December 18, 2009

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

The payment of remuneration, including retirement allowances (severance pay), to company directors in Japan is strictly governed by corporate law. The fundamental principle is that such payments require proper authorization, typically through the company's articles of incorporation or a resolution of its shareholders' meeting. This rule is designed to prevent self-dealing by directors and ensure shareholder oversight. But what happens when a director receives a retirement allowance without this explicit formal approval, particularly in a closely-held company where informal practices might be common? If the company later demands the return of this allowance, can the director resist, arguing that the demand is unfair under the circumstances?

This complex interplay between strict legal requirements and equitable considerations was at the heart of a notable decision by the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on December 18, 2009.

The Bedrock Principle: Authorization for Director Remuneration

Japanese company law, as affirmed in previous Supreme Court rulings (such as the 2003 Tomaruya Housing case, A21 in the PDF summary ), mandates that a director has no specific legal right to claim remuneration—which includes retirement allowances—unless the amount and terms are set either in the company's articles of incorporation or by a valid resolution of its shareholders' meeting. Unanimous consent of all shareholders can also, in some contexts, be considered equivalent to a shareholders' meeting resolution.

Consequently, if a director receives such payments without proper authorization, those payments are considered, in principle, to constitute unjust enrichment, and the company generally has a right to claim their return.

The X K.K. Case: A Closely-Held Company and Its Practices

The case involved X K.K., a company, and its former director, Y.

- Company Background: X K.K. was a closely-held corporation, effectively controlled by its Representative Director (the "Rep Director"), who was the child of the company's founder and held 99.24% of the company's shares.

- Internal Rules and Usual Practice: The company had internal rules for calculating director retirement allowances. Its usual practice for paying these allowances to retiring directors was based on the Rep Director's internal approval and did not typically involve a prior, formal shareholders' meeting resolution authorizing each specific payment. Instead, approval by the shareholders was generally sought retrospectively through the approval of the company's financial statements at the annual general meeting, which would list allowances already paid.

- Y's Retirement and Payment: Y, a long-serving director since 1972, retired at the end of December 2005. Around February 2006, the Rep Director initially informed Y that no retirement allowance would be paid. In response, Y, through a lawyer, sent a formal demand letter on March 2, 2006, requesting payment of the retirement allowance calculated according to the company's internal rules. Approximately ten days later, on March 13, 2006, X K.K. wired Y a sum of 47,456,433 yen, which was the amount calculated based on the internal rules.

- Lack of Formal Approval for Y's Payment: Crucially, this specific wire transfer to Y was made without a formal shareholders' meeting resolution authorizing it, and also without the explicit internal approval or "決済" (kessai - final decision/approval) of the Rep Director, which was part of the company's usual (albeit informal) process. Furthermore, this payment to Y was not disclosed in the financial statements subsequently approved at the shareholders' meeting.

- Company's Demand for Return: In October 2006, X K.K. entered civil rehabilitation proceedings. Nearly a year after the payment to Y, on February 21, 2007, X K.K. sent Y a letter demanding the return of the 47.456 million yen, asserting that the payment was not a lawful retirement allowance. Y refused to return the money.

- Y's Defense: In the ensuing lawsuit brought by X K.K. to recover the funds, Y argued that the company's demand for repayment was a violation of the principle of good faith (shingisoku) and an abuse of rights (kenri no ranyō).

The High Court had ruled in favor of X K.K., ordering Y to return the money, finding that Y's defense based on good faith and abuse of rights was not applicable. Y appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (December 18, 2009)

The Supreme Court, in a majority decision (with one dissenting opinion), quashed the High Court's ruling and remanded the case for further consideration of Y's equitable defenses.

Unjust Enrichment Affirmed (In Principle)

The Supreme Court began by reaffirming the general legal principle: since there was no shareholders' meeting resolution (or an equivalent authorization, such as an explicit approval by the Rep Director that might substitute for a formal resolution given X K.K.'s ownership structure and past practices) specifically authorizing the retirement allowance payment to Y, Y had no established legal right to it. Therefore, Y's receipt of the funds was, on its face, an instance of unjust enrichment.

However, a Claim for Return Can Be Barred by Good Faith/Abuse of Rights

This was the pivotal part of the ruling. The Supreme Court found that the High Court had dismissed Y's defense too hastily. It held that, under the specific circumstances presented, X K.K.'s subsequent demand for the repayment of the allowance could indeed be barred as being contrary to the principle of good faith or as an abuse of the company's right to claim recovery.

The Court identified several factors that, if established, would support Y's defense:

- Company's Established (Though Informal) Practice: X K.K. had a consistent history of paying retirement allowances to directors based on the Rep Director's approval (who was also the dominant shareholder), bypassing the need for prior, specific shareholders' meeting resolutions for each payment. This established practice created a certain environment of expectation.

- Y's Reasonable Belief Following Demand: After Y made a formal written demand for payment through a lawyer, citing the company's internal rules, the money was wired to Y's account relatively quickly (within about ten days). The Supreme Court stated that, unless Y had somehow colluded with the person who made the unauthorized transfer, it would have been "understandable" (無理からぬものがある - murikaranu mono ga aru) for Y to believe that the Rep Director had, in fact, approved this payment in line with past practice, despite the earlier indication of non-payment.

- Company's Significant Delay in Demanding Return: X K.K. waited for nearly a year after making the payment before formally demanding its return from Y. Such a delay could reinforce Y's belief that the payment was considered final.

- Rep Director's Potential Tacit Condonation: The Supreme Court suggested that if further factual investigation revealed that the Rep Director (the controlling shareholder) became aware of the payment to Y shortly after it was made (especially given Y's formal demand letter) and took no action for a considerable period, this inaction could be interpreted as tacitly condoning or acquiescing to the payment.

- Y's Performance as a Director: Y had also argued that his performance and contributions to the company were comparable or superior to those of other retired directors who had duly received their retirement allowances. The Supreme Court indicated that this was a relevant factor to be considered in assessing the overall fairness of demanding repayment.

Conclusion on the Defense

Considering these potential factual elements, the Supreme Court reasoned that unless X K.K. could demonstrate "special circumstances" – for instance, a legitimate and objective reason why Y, specifically, should not have received a retirement allowance despite his service record and the company's general practices – then demanding the return of the money already paid to Y could be deemed an abuse of rights or a violation of the principle of good faith. The fact that X K.K. had subsequently entered civil rehabilitation proceedings did not, in itself, automatically negate this potential equitable defense available to Y.

Outcome: The Supreme Court concluded that the High Court had failed to adequately examine the facts pertinent to Y's defense of good faith violation and abuse of rights (particularly concerning the Rep Director's awareness of the payment and Y's performance). Therefore, the High Court's decision, which had ordered Y to repay the allowance, was quashed, and the case was remanded for a more thorough examination of these equitable defenses. (It should be noted that one Justice dissented, arguing that the High Court's conclusion was correct and that the statutory requirement for authorization of retirement allowances should be strictly upheld, finding insufficient grounds to bar the company's claim for return).

Significance and Implications

The Supreme Court's 2009 decision is highly significant for several reasons:

- Confirms General Rule but Introduces Equitable Limits: The ruling strongly upholds the fundamental legal principle that director remuneration, including retirement allowances, requires proper authorization (typically by shareholders' meeting resolution or a provision in the articles of incorporation). Payments made without such authorization are, in principle, unjust enrichment.

- Good Faith and Abuse of Rights as a Shield for Directors: Critically, however, the decision establishes that the equitable principles of good faith and abuse of rights can serve as a valid defense for a director against a company's subsequent claim to recover such unauthorized payments. This is particularly likely in closely-held companies where corporate formalities are often relaxed, and where the company's own conduct, or that of its controlling shareholder, contributes to the director's reasonable belief that the payment was legitimate and final.

- Highly Fact-Dependent Analysis: The applicability of this equitable defense is not automatic. It requires a meticulous examination of the specific circumstances of each case, including the company's established practices for such payments, the knowledge and actions (or inaction) of the controlling shareholder(s), the director's performance and contributions, the circumstances surrounding the payment, and the reasons for and timing of any subsequent demand for its return.

- Guidance for Closely-Held Companies: This case offers particularly important guidance for closely-held companies, where the distinction between management and ownership often blurs, and formal corporate procedures may not always be followed with the same rigor as in publicly listed companies. It suggests that controlling shareholders cannot simply disregard past informal practices or their own acquiescence and later rely on a lack of formal resolutions to claw back payments if doing so would be unjust.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2009 decision concerning X K.K. and its former director Y serves as a vital reminder of the necessity for formal authorization when paying director retirement allowances. However, it also carves out an important equitable safety net. The ruling demonstrates that a company's attempt to reclaim such payments, even if they were initially made without strict formal approval, can be barred under the doctrines of good faith and abuse of rights if the specific factual context—particularly the company's prior practices, the conduct of its controlling shareholder(s), and the director's reasonable reliance—would make such a reclaim profoundly unfair. This judgment encourages a holistic assessment of fairness, especially in the often less formal environment of closely-held companies, balancing strict legal requirements with overriding equitable considerations.