Passenger Injury Insurance Payouts: A Windfall for Tortfeasors or Separate Comfort for Victims? A 1995 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Judgment Date: January 30, 1995

Court: Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench

Case Name: Damages Claim Case

Case Number: Heisei 3 (O) No. 1038 of 1991

Introduction: The Interplay of Insurance Benefits and Tort Damages

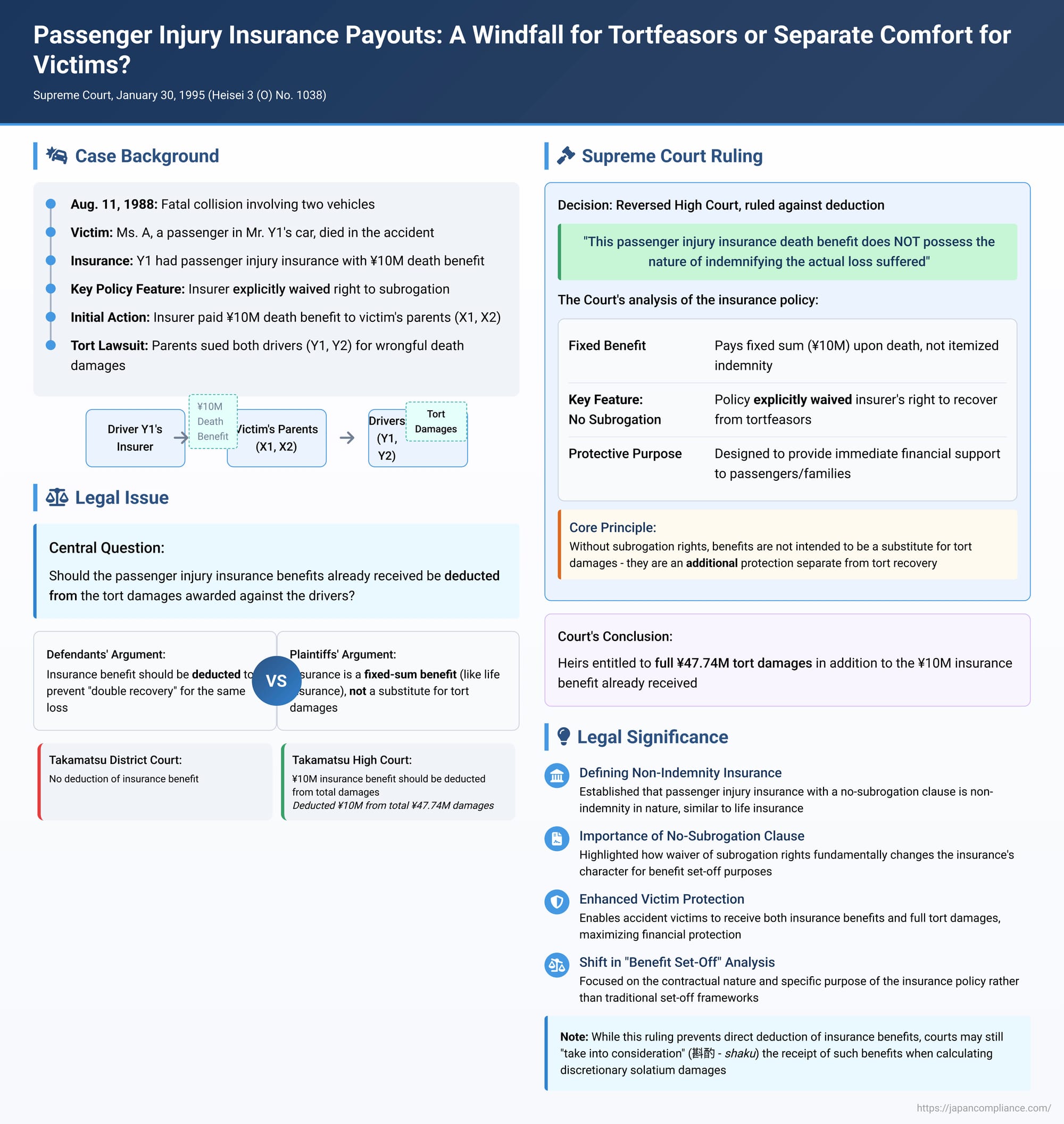

When an individual is injured or killed in an accident due to the negligence of a third party, the financial aftermath can be complex. The victim or their surviving family members typically have a tort claim against the responsible party (the tortfeasor) for damages, including medical expenses, lost income, and compensation for pain and suffering (solatium). In many instances, particularly in automobile accidents, insurance policies may also come into play. One such type of coverage common in Japan is Passenger Injury Insurance (搭乗者傷害保険 - tōjōsha shōgai hoken), which is often an endorsement or component of an automobile insurance policy. This insurance provides specified benefits if a passenger in the insured vehicle is injured or killed, regardless of who was at fault for the accident.

A crucial legal question then arises: if a victim or their heirs receive benefits under a Passenger Injury Insurance policy, should those insurance payments be deducted from the amount of damages they are entitled to recover from the tortfeasor? This issue, often framed within the legal doctrine of "benefit set-off" (損益相殺 - son'eki sōsai), seeks to prevent the claimant from receiving a "double recovery" for the same loss. However, its application depends heavily on the nature of the insurance benefit – is it intended to indemnify (make good) the actual loss also covered by the tort claim, or is it a separate, fixed benefit that the insured is entitled to irrespective of their tort recovery, perhaps like a life insurance payout? A key indicator in this determination is often whether the insurer has the right to "subrogate" – that is, to step into the victim's shoes and recover what it paid from the tortfeasor.

In 1995, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark decision that provided significant clarification on how Passenger Injury Insurance benefits, particularly those paid under a policy that explicitly excluded the insurer's right of subrogation, should be treated in relation to a tort damages award.

The Factual Background: A Fatal Collision and an Insurance Payout

The case arose from a fatal automobile collision that occurred on August 11, 1988. Ms. A was a passenger in a car being driven by Mr. Y1. This vehicle was involved in a collision with another car driven by Mr. Y2. Tragically, Ms. A died as a result of the injuries she sustained in the accident.

Ms. A's surviving heirs (her parents, referred to as X1 and X2) subsequently filed a lawsuit against both drivers, Mr. Y1 and Mr. Y2, seeking compensation for the wrongful death of their daughter. Their claims were based on general tort law principles (Article 709 of the Japanese Civil Code) and specific provisions of Japan's Compulsory Automobile Liability Insurance Act (CALI Act, or 自賠法 - Jibai-hō, Article 3).

Mr. Y1, the driver of the car in which Ms. A was a passenger, had an automobile insurance policy (referred to as "the subject insurance contract"). This policy included Passenger Injury Insurance coverage. Under the terms of this Passenger Injury Insurance clause ("the subject clause"), a death benefit of 10 million yen was payable in the event of a covered fatality. Following Ms. A's death, Mr. Y1's insurer (B Insurance Company, a non-party to this specific Supreme Court appeal but the original payer of the benefit) paid this 10 million yen Passenger Injury Insurance death benefit to Ms. A's heirs, X1 and X2.

A crucial feature of Mr. Y1's Passenger Injury Insurance clause was that it explicitly stipulated that if the insurer (B Insurance Company) paid out this death benefit, it would NOT acquire by subrogation any right to claim damages that the deceased passenger's heirs (X1 and X2) might have against any third party responsible for the death (which could include Mr. Y1 himself, or Mr. Y2).

The Core Legal Dispute: Should the Passenger Injury Insurance Benefit Be Deducted from the Tort Damages Awarded Against the Drivers?

In the tort lawsuit brought by X1 and X2 against the two drivers, Mr. Y1 and Mr. Y2, the defendants argued that the 10 million yen Passenger Injury Insurance benefit that X1 and X2 had already received from B Insurance Company (Mr. Y1's insurer) should be deducted from the total amount of damages that the court might find Mr. Y1 and Mr. Y2 liable to pay for Ms. A's wrongful death. Their contention was that failing to deduct this insurance payment would result in X1 and X2 receiving an unfair "double recovery" for the same loss.

X1 and X2, on the other hand, argued vigorously against any such deduction. They asserted that the Passenger Injury Insurance was intended to provide a fixed sum benefit upon the occurrence of a covered event (death or injury to a passenger), akin to a life insurance payout. They emphasized that since the insurer had contractually waived its right to subrogation, the insurance benefit was not intended to be a substitute for, or a reduction of, the damages recoverable from the tortfeasors. Therefore, they contended, they should be entitled to receive both the full insurance payout and the full measure of their tort damages from Mr. Y1 and Mr. Y2.

Lower Courts' Rulings on the Deduction Issue

The lower courts came to different conclusions on this critical point:

- Court of First Instance (Takamatsu District Court): This court, after assessing the total damages for Ms. A's wrongful death, appears to have awarded that sum without deducting the 10 million yen Passenger Injury Insurance benefit. (The Supreme Court judgment notes that the High Court changed the first instance award by making the deduction, which implies the first instance court had not made such a deduction).

- Appellate Court (Takamatsu High Court): The High Court first recalculated the total amount of damages that X1 and X2 had suffered due to Ms. A's death, arriving at a figure of approximately 47.74 million yen. However, it then accepted the argument made by the defendants (Mr. Y1 and Mr. Y2, an argument reportedly added at the appeal stage by Mr. Y1) that the 10 million yen Passenger Injury Insurance benefit already received by X1 and X2 should be deducted from this total. The High Court reasoned that this insurance benefit was intended to compensate for the loss suffered by Ms. A. Consequently, it ordered Mr. Y1 and Mr. Y2 to pay X1 and X2 a net amount of approximately 37.74 million yen.

X1 and X2, disagreeing with this deduction, appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision (January 30, 1995): No Deduction – Insurance Benefit Characterized as Non-Indemnity in This Context

The Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, partially reversed the High Court's decision. Specifically, it overturned the High Court's ruling that the 10 million yen Passenger Injury Insurance benefit should be deducted from the tort damages. The Supreme Court ordered Mr. Y1 and Mr. Y2 to pay X1 and X2 the full amount of damages as assessed by the High Court (approximately 47.74 million yen), without any deduction for the Passenger Injury Insurance benefits already received.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

Analysis of the Nature of the Passenger Injury Insurance Contract and Its Death Benefit

The Court meticulously examined the terms and conditions of the Passenger Injury Insurance clause that was part of Mr. Y1's automobile insurance policy. It highlighted several key features:

- The overall auto insurance contract held by Mr. Y1 provided coverage for his legal liability to third parties and, in addition, provided for this separate Passenger Injury death benefit of 10 million yen.

- The Passenger Injury Clause specified that it covered individuals "riding in" the insured vehicle. If such a person suffered an injury as a result of an accident arising from the vehicle's operation and, as a direct consequence, died within 180 days of the accident, the insurer was obligated to pay the full stipulated death benefit (10 million yen) to the deceased insured person's legal heirs.

- Crucially, the Supreme Court noted, the policy also contained a provision explicitly stating that if the insurer paid out this Passenger Injury death benefit, it would NOT acquire by subrogation any rights that the deceased passenger's heirs might have to claim damages from any third parties responsible for the death.

Conclusion on the Nature of the Benefit: Not Indemnity for Loss

Based on these specific terms – particularly the payment of a fixed sum upon the contingency of death and, most importantly, the explicit waiver of the insurer's right to subrogation – the Supreme Court concluded that the death benefit paid under this particular Passenger Injury Clause does NOT possess the nature of indemnifying the actual, itemized loss suffered by the deceased insured person or their heirs. (The Court used the precise phrase: 被保険者が被った損害をてん補する性質を有するものではない - hihokensha ga kōmutta songai o tenpo suru seishitsu o yūsuru mono dewa nai).

Rationale – Protecting Passengers with a Fixed Sum Benefit

The Supreme Court provided the following rationale for this characterization:

The Passenger Injury Clause, especially when considering that policyholders, their family members, friends, and other acquaintances frequently ride as passengers in insured vehicles, should be understood as being intended to protect these passengers (or their heirs in the event of death) by providing them with a defined, fixed sum of money (定額の保険金 - teigaku no hokenkin) upon the occurrence of a covered event (such as death or a specified injury).

The Court viewed this benefit as being distinct from, and not primarily designed as, a like-for-like reimbursement of specific, itemized economic losses in the same way that third-party liability insurance or some forms of first-party property indemnity insurance operate.

Therefore, No Deduction (No Benefit Set-Off) from Tort Damages

Because the Passenger Injury Insurance death benefit was characterized by the Supreme Court as being non-indemnity in nature (more akin to a fixed benefit payable upon a defined contingency, similar in some respects to a life insurance payout, particularly given the no-subrogation clause), the Court held that it should NOT be deducted from the amount of damages that the tortfeasors (Mr. Y1 and Mr. Y2) were found liable to pay to the victim's heirs (X1 and X2) in their wrongful death claim.

The heirs were entitled to receive the full measure of their tort damages from the defendants, in addition to the full 10 million yen Passenger Injury Insurance benefits they had already received from Mr. Y1's insurer.

Analysis and Key Implications of the Ruling

This 1995 Supreme Court decision was a landmark judgment in Japanese law, providing crucial clarification on the treatment of Passenger Injury Insurance benefits in the context of third-party tort claims.

1. Defining Passenger Injury Insurance (When Accompanied by a "No Subrogation" Clause) as Non-Indemnity for Set-Off Purposes:

The most significant aspect of this ruling is its clear characterization of Passenger Injury Insurance – at least when it provides for a fixed sum benefit for events like death or injury and, critically, includes a clause where the insurer explicitly waives its right to subrogation – as being non-indemnity in nature for the specific purpose of determining whether it should be set off against a tort damages award. This distinguished it from traditional third-party liability insurance, where the principle of indemnity is paramount.

2. The Decisive Significance of the "No Subrogation" Clause:

The explicit contractual waiver of subrogation rights by the insurer in the Passenger Injury Insurance policy was a linchpin in the Supreme Court's reasoning. The right of subrogation is a hallmark of pure indemnity insurance; it allows the insurer to recover its payment from the party at fault, thereby preventing the insured from receiving a "double recovery" for the exact same financial loss and ensuring that the ultimate cost falls on the wrongdoer. The absence of this right of subrogation strongly indicated to the Court that the Passenger Injury Insurance benefit was not intended to be a direct substitute for, or a direct indemnification of, the same losses recoverable in a tort action. Instead, it was seen as a separate, additional benefit.

3. Consideration of the Policyholder's Intent and the Goal of Passenger Protection:

The Supreme Court's rationale also gave considerable weight to the presumed intent of a policyholder who takes out Passenger Injury Insurance. The Court viewed the primary purpose of such coverage as being to provide an additional, readily available financial benefit to passengers or their families in the event of an accident, often irrespective of the complex and potentially lengthy process of determining and recovering damages through tort liability claims. It is perceived as a measure of direct protection and solicitude for those individuals who are passengers in the insured vehicle.

4. A Shift in Approach from Traditional "Benefit Set-Off" Frameworks?:

Legal commentary (such as the PDF provided with this case) has noted an interesting aspect of the Supreme Court's reasoning in this 1995 judgment. While previous Supreme Court decisions that had denied the set-off of other types of insurance benefits (like fire insurance payouts or certain fixed-sum personal accident policy benefits) from tort damages had often engaged with the traditional Japanese legal framework and arguments typically used to decide "benefit set-off" (son'eki sōsai) issues – for example, by discussing whether the insurance benefit received by the plaintiff arose from the same underlying cause as the tortious loss, or whether it was intended by its nature to relieve the tortfeasor's ultimate burden – this 1995 judgment took a somewhat different tack. It focused more directly and emphatically on the contractual nature and specific purpose of the Passenger Injury Insurance policy itself, as evidenced by its terms (especially the no-subrogation clause), to determine its character (indemnity vs. non-indemnity) and, from that characterization, to decide the set-off issue.

5. Consistency with Prevailing Academic Views Favoring No Deduction:

As noted in the legal commentary, even before this definitive Supreme Court ruling, a significant body of academic opinion in Japan had argued against the deduction of Passenger Injury Insurance benefits from tort damages claims. This was particularly the case where, as in this instance, the policyholder of the Passenger Injury Insurance was also one of the tortfeasors liable for the passenger's injuries or death. The argument often advanced was that the policyholder's likely intent in purchasing Passenger Injury Insurance coverage was to provide an additional layer of protection and benefit for their passengers, not primarily to reduce their own (or their liability insurer's) potential exposure in a tort action. The Supreme Court's 1995 decision largely aligned with this prevailing scholarly sentiment.

6. The Unresolved (by this Judgment) Issue of "Consideration" of Benefits in Solatium Calculation:

It is important to note a related but distinct issue that this Supreme Court judgment did not explicitly address. Even if Passenger Injury Insurance benefits are not directly deducted as a formal set-off from the total calculated tort damages, Japanese courts, both before and after this 1995 Supreme Court ruling, have sometimes engaged in a practice of "taking into consideration" (斟酌 - shaku) the fact that such insurance benefits were received by the victim or their heirs when the court calculates the specific amount of solatium (damages for non-pecuniary losses such as pain, suffering, and emotional distress). This practice of "consideration" is not a direct, yen-for-yen deduction, but rather a factor that might influence the court's discretionary assessment of what constitutes a fair and reasonable amount for solatium in light of all the circumstances, including other benefits received. This practice is not uniform and often depends on specific factors, such as who paid the premiums for the Passenger Injury Insurance (e.g., the victim themselves, or the tortfeasor). The 1995 Supreme Court judgment did not explicitly affirm or deny the appropriateness of such "consideration" in the solatium assessment process, leaving it as an area of continued judicial practice and ongoing academic debate.

Conclusion

The January 30, 1995, Supreme Court of Japan decision delivered a clear and highly influential answer to a long-debated question regarding the treatment of Passenger Injury Insurance benefits in the context of third-party tort claims. The Court ruled that when such an insurance policy provides for a fixed death benefit (or injury benefit) and, crucially, contains a clause whereby the insurer explicitly waives its right to subrogation, the insurance benefits paid to a deceased passenger's heirs (or to an injured passenger) are not to be deducted from the amount of damages that are recoverable from the at-fault tortfeasor(s).

The Supreme Court carefully characterized this specific type of Passenger Injury Insurance as being non-indemnity in nature. It viewed the coverage as being intended to provide a direct, defined, and fixed benefit to protect passengers and their families upon the occurrence of a covered event, rather than serving as a mere indemnification of the specific economic losses that would also be recoverable in a tort action against the responsible parties.

This landmark ruling ensures that victims of traffic accidents or their surviving families can receive the full benefits provided by such Passenger Injury Insurance policies in addition to their full entitlement to damages from those who caused the harm through their negligence. The decision strongly emphasizes the importance of carefully examining the specific terms of the insurance policy, particularly the presence or absence of a "no subrogation" clause, in determining the fundamental nature of the insurance benefits and how they should interact with recoveries available under tort law. It represents a significant clarification that has enhanced the overall financial protection available to individuals involved in automobile accidents in Japan.