Partner's Pay: Salary or Business Income? Japan's Supreme Court Clarifies Taxation of Labor Compensation from Partnerships

Judgment Date: July 13, 2001

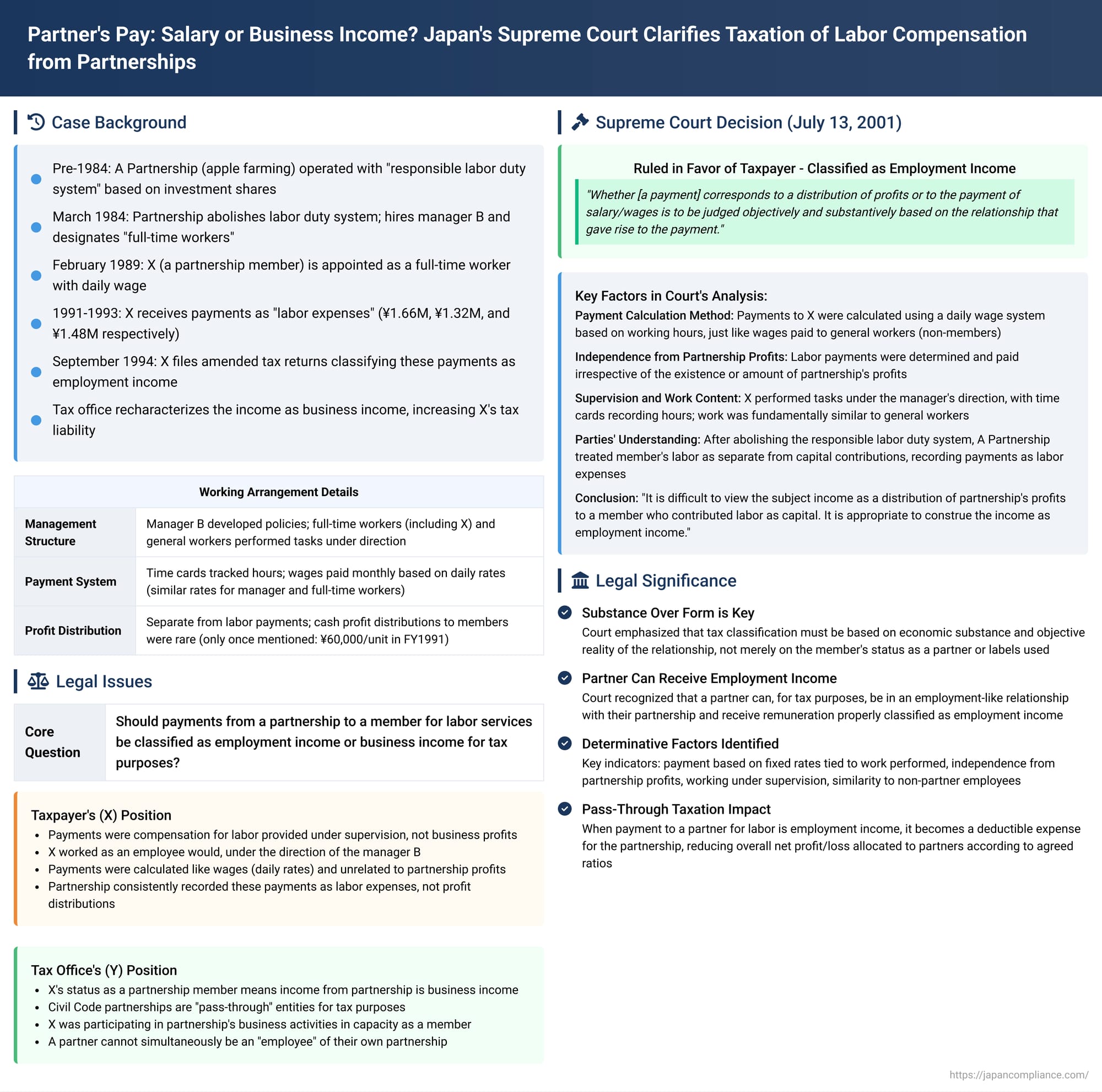

In a significant ruling that delves into the nuanced tax classification of payments made by a Civil Code partnership to one of its members for labor services, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan provided crucial guidance. The case centered on whether such payments should be treated as employment income (salary/wages) or as a distribution of business income to the partner. The Court emphasized a substance-over-form approach, looking at the objective realities of the working relationship and payment structure rather than relying solely on the recipient's status as a partner.

Background: An Apple Farming Partnership and a Member's Compensation

The appellant, X, was a member of "A Partnership," a Civil Code partnership (minpō-jō no kumiai) established for the purpose of apple production. Initially, A Partnership operated under a "responsible labor duty system," where members or their families were obligated to contribute labor according to their investment share, with financial adjustments made for excesses or shortfalls in labor provided. No direct wages were paid for this obligatory labor.

However, as the apple trees matured and the demand for consistent, skilled labor grew, this system became impractical. In March 1984, the partnership's general meeting decided to abolish the responsible labor duty system. Instead, apple production was to be carried out by a hired manager, designated "full-time workers" (senjūsha - 専従者), and general workers. A non-member, B, who had relevant experience, was appointed as the manager. Another partner, C, was appointed as one of the full-time workers.

X, also a member of A Partnership, had initially worked as a general worker after the abolition of the labor duty system. In February 1989, at a general meeting of A Partnership, X was formally appointed as a full-time worker, with his daily wage increased.

Operational Structure and Payments to X

The operational structure of A Partnership after these changes was as follows:

- The manager (B) was responsible for developing basic policies and determining work plans and procedures.

- Full-time workers (like X and C) and general workers performed their tasks under the manager's direction.

- While full-time workers might handle tasks requiring more experience (such as pesticide application), their general work content was largely similar to that of the general workers. They essentially assisted the manager.

- Working hours for everyone involved in production—manager, full-time workers, and general workers—were recorded using time cards.

- Wages were generally paid monthly, calculated on a daily rate basis. The daily rates for B (manager), C (full-time worker), and X (full-time worker) were very similar. General workers typically received a daily rate about 1,000 yen lower, reflecting differences in workload, skill, and experience.

- A Partnership conducted annual financial settlements. However, cash distributions of profits to members based on their contribution units were rare; the only such instance mentioned was a payment of 60,000 yen per unit in Fiscal Year (FY) 1991. Other profits were generally retained for purposes such as purchasing agricultural machinery or funding future operational expenses.

- Importantly, after the abolition of the responsible labor duty system, the wages paid to the manager (B) and the full-time workers (including X and C) were consistently recorded as labor expenses in A Partnership's books.

The Tax Dispute

X received payments from A Partnership, designated as labor expenses by the partnership, amounting to approximately 1.66 million yen in FY1991, 1.32 million yen in FY1992, and 1.48 million yen in FY1993. In September 1994, X filed amended income tax returns for these years, classifying these amounts as employment income (給与所得 - kyūyo shotoku).

The head of the relevant tax office, Y (appellee), disagreed with this classification. Y issued corrective tax assessments, recharacterizing X's income from these payments as business income (事業所得 - jigyō shotoku) and, as a result, imposed underpayment penalties. X's internal administrative appeal to the National Tax Tribunal was unsuccessful; the Tribunal sided with the tax office, reasoning that X, as a partner, was working independently and on an equal footing with the manager B, making the income derived from the partnership's business activities properly classifiable as business income. X then initiated a lawsuit to overturn the tax office's assessments.

Lower Court Rulings: A Split Decision

- Morioka District Court (First Instance): The District Court ruled in favor of X. It found that X's labor was provided without the elements of operating at his own risk and calculation, which are characteristic of business income. The payments were, in its view, merely remuneration for labor provided and thus should be classified as employment income.

- Sendai High Court (Appellate Court): The High Court reversed the District Court's decision, ruling in favor of Y (the tax office). Its reasoning was more formalistic:

- It started from the premise that income generated by a Civil Code partnership (which is not a separate taxable entity) is attributed directly to its members and taxed at their level.

- The High Court held that any income a partner receives in their capacity as a partner from the partnership's business activities retains the character of business income, regardless of how it is labeled (e.g., salary, bonus).

- Since X was a partner participating in the partnership's apple production business and received these payments in that context, the payments were considered a distribution of the partnership's business income. Therefore, they constituted business income for X.

X appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Analysis: Substance Over Form

The Supreme Court overturned the Sendai High Court's decision and reinstated the Morioka District Court's ruling, ultimately classifying X's income as employment income. The Court's reasoning emphasized the need for an objective and substantive analysis of the relationship between the partner and the partnership.

Framework for Determining Income Classification

The Supreme Court laid down the following analytical framework:

"When a member of a Civil Code partnership receives monetary payment from the partnership for having engaged in the partnership's business, whether the said payment corresponds to a distribution of profits generated from the partnership's business, or to the payment of salary/wages, etc., pertaining to employment income under Article 28, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act, is to be judged objectively and substantively. This judgment should be based on an examination of:

- The intention or understanding of the partnership and the member concerning the legal relationship that gave rise to the payment.

- The specific manner in which the labor was provided and the payment was made."

Crucially, the Court added two important clarifications:

- "A monetary payment to a member does not automatically correspond to a distribution of profits merely because the recipient is a member."

- "Furthermore, classifying the income received by a member from such payment as salary/wages, etc., does not immediately entail recognizing the existence of a contradictory legal relationship between the partnership and the member (e.g., a partner being simultaneously an employer and employee in the same transaction)."

Application to X's Case

Applying this framework, the Supreme Court found several factors pointed towards X's income being employment income:

- Method of Calculating and Paying Remuneration: The labor payments made by A Partnership to X (and other full-time workers) were calculated based on a daily wage system, determined by working hours, just like the wages paid to general workers whose status as employees was clear. The differences in daily rates between full-time workers (like X) and general workers were attributable to factors like workload, skill level, and experience—typical considerations in setting employee wages. Moreover, the payments were made monthly in cash on a fixed payday, a method also used for general workers.

- Independence from Partnership Profits: The Court noted that cash distributions of partnership profits to members, based on their capital contribution units, had occurred only once (in FY1991). This contrasted sharply with the regular, fixed-rate labor payments. This led the Court to conclude that "the labor payments to full-time workers were determined and paid irrespective of the existence or amount of A Partnership's profits."

- Nature of Work Performed and Supervision: X and other full-time workers performed their tasks, like general workers, under the operational instructions and orders of the manager, B. Their working hours were meticulously recorded using time cards. Their actual work content was "fundamentally no different from that of general workers," with any variations attributable to differences in experience and skill. This led the Court to the view that "X and other full-time workers provided labor under the command and supervision of A Partnership's manager, in a position similar to that of general workers."

- Parties' Understanding and Historical Context: The facts indicated that A Partnership and its members, including X, understood the labor payments to full-time workers as being based on an employment-like relationship. This was further supported by the historical evolution of A Partnership's labor system. The initial "responsible labor duty system" (where members contributed labor as part of their partnership obligations) was abolished because it became recognized that employing hired labor was more rational and efficient for the apple production business. This shift to a system utilizing a manager, full-time workers, and general workers suggested that "after the abolition of the responsible labor duty system, the provision of labor by members who were full-time workers was treated similarly to that of general employees."

Conclusion: Payments Were Employment Income

Considering all these factual circumstances, the Supreme Court concluded:

"Even taking into account that X and other full-time workers, unlike general workers, were selected from among the partnership members at A Partnership's general meetings and held a position assisting the manager between the manager and general workers in apple production tasks, and that the responsible labor duty system was in place at the time of A Partnership's establishment, it is difficult to view the subject income received by X from A Partnership as labor expenses as a distribution of the partnership's profits to a member who contributed labor as capital. It is appropriate to construe the income related to the subject payments as employment income."

Judgment and Its Significance

The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's judgment, which had favored the tax office, and reinstated the first instance District Court's judgment, which had ruled in favor of X. This meant X's classification of the income as employment income was upheld.

This decision has several important implications for the taxation of partnerships and their members in Japan:

- Substance Over Form is Key: The ruling strongly emphasizes that the tax classification of payments made by a partnership to its members for labor services must be determined by the economic substance and objective reality of the relationship, rather than solely by the member's status as a partner or the labels used for the payments.

- Partner Can Receive Employment Income from Partnership: The Supreme Court effectively recognized that a partner can, for income tax purposes, be in an employment-like relationship with their own partnership regarding specific labor they provide, and receive remuneration that is properly classified as employment income rather than a share of business profits. The Court navigated the conceptual difficulty of a partner being an "employee" of their own firm by stating it doesn't necessarily create a "contradictory legal relationship."

- Determinative Factors: The judgment provides a clear set of factors that indicate an employment-like relationship for tax purposes:

- Payment based on fixed rates (e.g., daily or hourly wages) tied to work performed, rather than a share of profits.

- Payments made irrespective of the partnership's overall profitability.

- Working under the direction and supervision of a manager or another authority within the partnership.

- Similarity in work content and treatment (e.g., time cards, payment methods) to non-partner employees.

- The mutual understanding and intent of the parties, as evidenced by their conduct and how transactions are recorded.

- Impact on Partnership Taxation (Pass-Through Context): While Civil Code partnerships are generally "pass-through" entities (their income is allocated to partners and taxed at the partner level, the entity itself doesn't pay income tax), this ruling has implications for calculating the partnership's net income that is to be allocated. If a payment to a partner for labor is classified as employment income for that partner, it correspondingly becomes a deductible labor expense for the partnership, reducing the overall net profit (or increasing the net loss) to be allocated among all partners according to their agreed profit/loss sharing ratios.

This Supreme Court decision provides valuable guidance for partners and partnerships in structuring compensation for labor services provided by members, emphasizing that careful attention must be paid to the substantive nature of the arrangements to ensure correct income tax classification. It reinforces the judiciary's role in looking beyond formal labels to the underlying economic realities in tax matters.