Parking Rights in Condominiums: Who Keeps the Cash from "Sales" by Developers? A 1998 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment: October 22, 1998

Case Number: 1996 (O) No. 1559 (Supreme Court, First Petty Bench)

Introduction

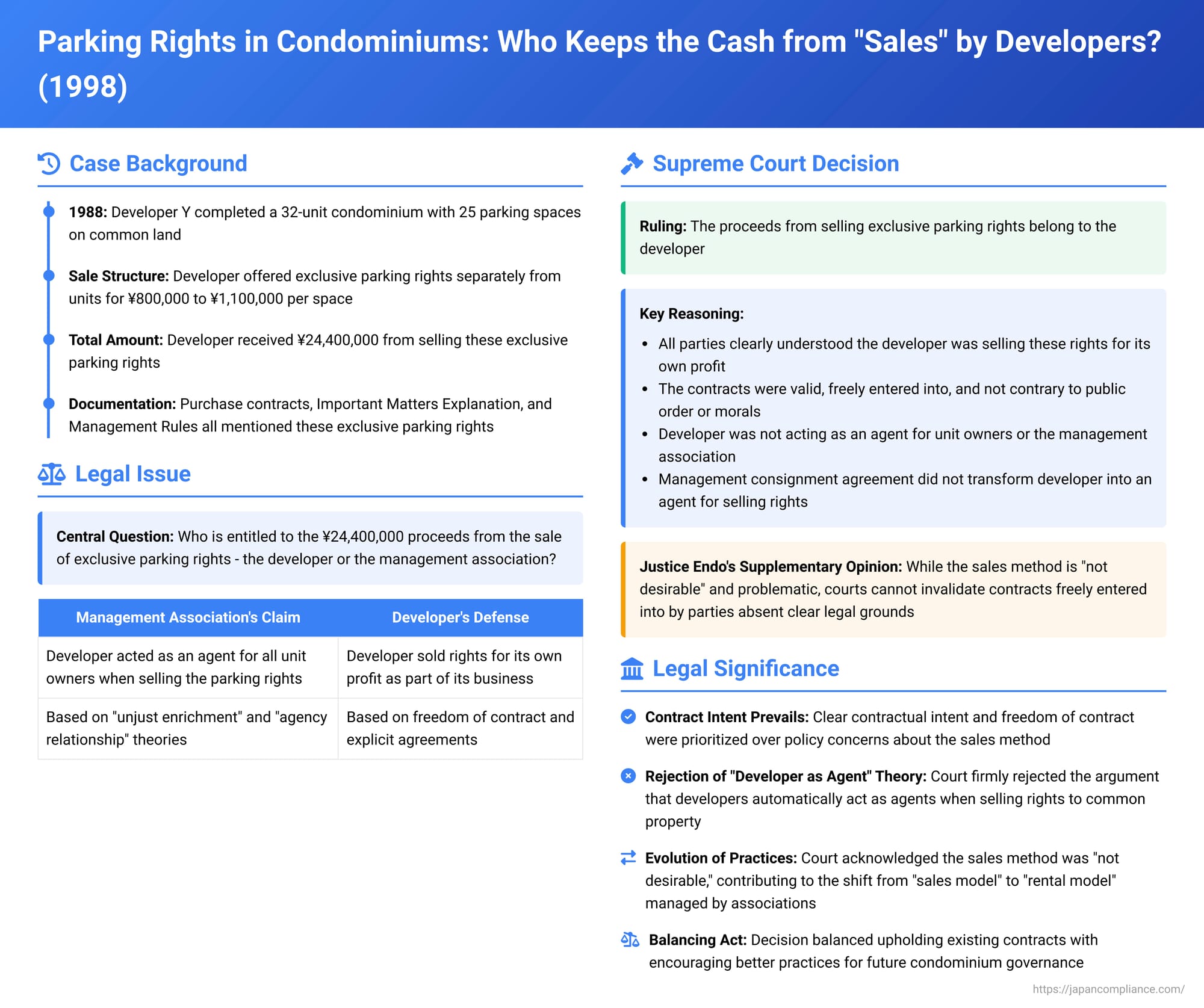

In condominium living, the use of common areas, particularly parking spaces, often becomes a complex issue. In Japan, a common practice in older condominium developments involved the developer, at the time of the initial sale of units, also "selling" or granting exclusive usage rights for specific parking spaces to certain unit buyers. This practice raised a fundamental question: who is entitled to the substantial sums of money paid by these buyers for such exclusive rights – the developer who structured the deal, or the condominium management association representing all unit owners who collectively own the common areas, including the land used for parking?

A Supreme Court decision on October 22, 1998, tackled this issue head-on, providing a significant precedent regarding the attribution of proceeds from the "sale" of parking space exclusive usage rights. This article delves into the facts of this case, the Supreme Court's reasoning, and the broader implications for condominium management and contractual practices in Japan.

Facts of the Case

The dispute involved a condominium developer, Y, and the president of the condominium's management association, X, acting on behalf of the association.

Condominium Development and Sale of Parking Rights:

In 1988, Y completed and sold units in a condominium complex consisting of 32 residential units. On the condominium's敷地 (shikichi - site/grounds), which is common property, Y established 25 parking spaces.

Concurrently with the sale of the condominium units (which included co-ownership shares in the land), Y offered interested unit buyers the opportunity to acquire exclusive usage rights for these parking spaces. These rights were sold separately from the condominium units themselves. The price for an exclusive parking usage right ranged from ¥800,000 to ¥1,100,000 per space. Y received a total of ¥24,400,000 from the sale of these rights.

Key Contractual Documents and Provisions:

Several documents detailed the arrangement for these parking rights:

- Purchase and Sale Agreement for Condominium Units (土地付区分建物売買契約書 - tochitsuki kubun tatemono baibai keiyakusho):

- Article 1 mentioned that the purchase price included "¥○○ as consideration for parking." This section was filled with a specific amount for buyers who purchased a parking right and left blank for those who did not.

- Article 9 stipulated that the buyer of a condominium unit acknowledged that a portion of the site would be used as parking with exclusive usage rights granted to specific unit owners. It also stated that buyers acquiring such rights must pay separately stipulated fees.

- Important Matters Explanation Document (重要事項説明書 - jūyō jikō setsumeisho): This document, provided to buyers before contract execution, included a section on "Stipulations in bylaws, etc., concerning exclusive usage rights." Under the "Parking" heading, it specified:

- "Persons entitled to exclusive use: Specific unit owners."

- "Existence of exclusive use common service expenses (parking fees): Yes, ¥500 per month per space."

- "Recipient of exclusive use common service expenses: Management Association."

This indicated that a separate, ongoing monthly fee for using the parking space would be paid to the management association, distinct from the initial lump sum paid to Y for the right itself.

- Management Consignment Agreement (管理委託契約書 - kanri itaku keiyakusho): The unit buyers initially entrusted Y with the management of the condominium building and grounds. This agreement stipulated that Y would hand over management duties to the management association (to be formed by all unit owners under the Condominium Ownership Act) within six months of the building's completion or when occupancy reached 80%, at which point the consignment agreement with Y would be terminated.

- Draft Management Rules (管理規約案 - kanri kiyaku an): Prepared by Y, these draft rules contained a provision stating that unit owners approved specific unit owners having exclusive usage rights for parking spaces, balconies, and rooftop terraces. These draft rules were later formally approved by all unit owners and became the condominium's official management rules (bylaws).

The Lawsuit:

The president of the management association, X, sued the developer, Y, to claim the ¥24,400,000 that Y had received from selling the exclusive parking usage rights. The primary claim was for the return of unjust enrichment (不当利得返還請求 - futō ritoku henkan seikyū). Alternatively, X claimed the funds based on an agency or mandate relationship (委任契約にもとづく受取物引渡請求 - inin keiyaku ni motozuku uketoributsu hikiwatashi seikyū), arguing that Y had sold these rights as an agent for the collective body of unit owners and was therefore obligated to hand over the proceeds.

The court of first instance found in favor of X on the alternative claim, agreeing that Y acted as an agent. The High Court upheld this decision. Y then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court, on October 22, 1998, reversed the lower courts' decisions and ruled in favor of the developer, Y. The Court found that the proceeds from the sale of the exclusive parking usage rights belonged to Y.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

1. Clear Agreement and Understanding Among Parties:

The Supreme Court first looked at the evidence of agreement. Based on the Purchase and Sale Agreement, the Important Matters Explanation Document, and the draft Management Rules, it was clear that:

- The exclusive parking usage rights were sold by Y to specific unit owners in conjunction with the condominium sales.

- The unit owners who acquired these rights understood they were gaining the ability to exclusively use those parking spaces.

- The unit owners who did not acquire these rights understood they were to acknowledge and accept this exclusive use by others.

All parties involved had a mutual understanding of this arrangement.

2. No Grounds to Invalidate the Sales Contract (Public Order or Morals):

The Court found no circumstances suggesting that the contracts for selling the exclusive parking usage rights were contrary to public order and morals (公序良俗違反 - kōjo ryōzoku ihan). There was no evidence, for example, that Y, as the developer, had exploited the buyers' lack of knowledge or imprudence to reap exorbitant profits under the guise of selling these rights.

3. Private Law Validity Despite Undesirability of the Practice:

The Court acknowledged a critical point: the practice of a developer selling exclusive usage rights for common areas when initially selling condominium units is "not desirable" (好ましいものとはいえない - konomashii mono to wa ienai). However, the Court stated that this undesirability, in itself, does not suffice to negate the private law validity of the contracts freely entered into by the parties. The agreements regarding the sale of these rights were, therefore, considered valid contractual arrangements.

4. Proceeds Belong to the Developer Based on Contractual Intent:

The Supreme Court then addressed the core issue of who was entitled to the ¥24,400,000. According to the terms of the Purchase and Sale Agreement, Y sold these exclusive usage rights for its own commercial benefit, as a business entity engaged in profit-making activity. The unit owners who purchased these rights also understood this to be the case. Therefore, the Court concluded that, according to the agreed-upon terms of the contracts, the proceeds from the sale of these rights belonged to Y.

5. Rejection of the "Developer as Agent" Argument:

The management association's alternative claim was based on the idea that Y was acting as an agent (受任者 - juninsha) for all unit owners (or the nascent management association) when it sold these rights. The Supreme Court firmly rejected this interpretation:

- Contradicts Parties' Intent: To interpret Y as having sold these rights on behalf of all unit owners, as their agent, would directly contradict the intentions of the parties as evidenced by the sales contracts. The contracts indicated a direct sale from Y (for its own account) to the individual buyers.

- Management Consignment Agreement Irrelevant to Sales Proceeds: The existence of the Management Consignment Agreement, under which Y temporarily managed the property, did not alter this conclusion. That agreement pertained to management duties, not to the initial sale of the property rights or exclusive usage rights for Y's own account as a developer.

- No General Presumption of Agency: The Court found no legal basis for a general presumption that, in every condominium development, the developer automatically acts as an agent for the collective of unit owners or the management association when it structures and sells exclusive usage rights as part of the initial offering. Such a sweeping interpretation would lack foundation, especially when it overrides the specific contractual terms and intentions of the parties involved.

Outcome:

The Supreme Court concluded that the lower courts had erred in their interpretation and application of the law. The judgment of the High Court was overturned. As the preliminary (alternative) claim for the handover of proceeds based on agency was found to be without merit, the part of the first instance judgment upholding that claim was also reversed, and the claim itself was dismissed. The litigation costs were to be borne by the management association (X).

Justice Endo's Supplementary Opinion

One of the justices, Endo, provided a supplementary opinion which, while concurring with the majority's conclusion, offered further reflections on the problematic nature of the sales method and the legal reasoning.

- Acknowledging the Problems: Justice Endo explicitly agreed with the appellant (management association) that the developer's practice of selling exclusive parking usage rights separately from the units is problematic. He highlighted two main concerns:

- Suspicion of "Double-Dipping": It raises suspicion that the developer might be profiting twice from the same land – once from selling the land as part of the condominium units (co-ownership share) and again by selling exclusive rights to use parts of that land.

- Potential for Future Disputes: This sales method creates fertile ground for future conflicts within the condominium community regarding the transferability of these rights, their duration, the imposition or increase of usage fees, etc., between those who hold the rights and the management association (or other unit owners).

He stated that such sales methods are indeed undesirable and should be "swiftly eradicated."

- Limitations of Legal Interpretation under Freedom of Contract: However, Justice Endo emphasized that while these points are valid for legislative reform or administrative guidance, legal interpretation under the existing law, which is fundamentally based on the principle of freedom of contract, has its limits.

- "Double-Dipping" Not Always Provable: It cannot be assumed that this sales method always results in a double profit for the developer. A developer might strategically lower the initial sales price of the condominium units themselves because they anticipate additional revenue from selling parking rights. If pricing is based on such economic rationale, the proceeds from the parking rights sales would naturally belong to the developer who structured the overall pricing for their own profit. Determining the "fairness" or "reasonableness" of the developer's pricing strategy after the fact is practically difficult, and such difficulty cannot be a reason to invalidate the sales method or interpret the destination of the proceeds contrary to the parties' clear intentions.

- Future Conflicts Don't Invalidate Current Contracts: The mere possibility of future disputes does not, by itself, justify restricting the private law validity of the sales method. Such problems must be addressed separately through the interpretation and application of relevant laws, such as the Condominium Ownership Act, to find appropriate solutions.

- Conclusion on Contract Validity and Agency: Unless there is clear evidence of exploitation (e.g., usurious pricing amounting to a violation of public order and morals) or objective proof that the developer unjustly enriched themselves through double-dipping (which could give rise to a claim for unjust enrichment), contracts for the sale of exclusive usage rights entered into by consenting parties cannot be invalidated. Furthermore, the fact that a developer temporarily performs some management duties before the management association is fully operational does not transform the developer into an agent for the sale of these rights, overriding the explicit contractual intent of the parties. He characterized the lower courts' reasoning as an attempt to achieve a desirable outcome by adopting a strained legal construction beyond the bounds of sound legal interpretation.

Justice Endo clarified that he supported the majority opinion because it represented the logical conclusion under current law, not because it actively endorsed the controversial sales method.

Analysis and Broader Implications

This 1998 Supreme Court decision was a key judgment in a series of cases around that time addressing the complex issues surrounding exclusive usage rights in condominiums, particularly for parking.

1. Context of Broader Disputes and a Series of Rulings:

The problem of parking rights in condominiums often manifests in two main types of disputes:

- Developer vs. Management Association: Conflicts over the initial allocation of rights by the developer (either by "selling" them or "reserving" them for themselves or designated parties) and, crucially, who is entitled to any financial consideration paid for these rights. The present case is a prime example of this type.

- Right-Holders vs. Management Association: Conflicts between those unit owners who possess exclusive parking rights and the management association (representing all owners, including those without such rights). These disputes can concern attempts by the association to terminate these rights, convert them to paid-use under the association's control, increase usage fees, or regulate their transfer.

The Supreme Court delivered four significant judgments related to parking rights in October and November 1998. The general thrust of these rulings, including the one discussed here, was to uphold the validity of the initial establishment of exclusive parking usage rights when based on clear and explicit agreements among the parties involved (developer and initial buyers). In cases following the "sale model," where the developer sold these rights, the proceeds were generally found to belong to the developer. However, the Court also signaled that the initial setup was not immutable; subsequent adjustments to balance the interests of all unit owners (e.g., regarding usage fees for common property) could be made by the management association through proper procedures under the Condominium Ownership Act, particularly considering provisions related to "special impact" on certain unit owners (区分所有法31条1項後段 - kubun shoyū hō dai sanjūichi jō ikkō kōdan).

2. Rejection of the "Developer as Agent" Theory:

This specific judgment is notable for its firm rejection of the "developer as agent theory" (分譲業者受任者説 - bunjōgyōsha juninsha setsu). This theory, which had gained some traction in academic discussions and some lower court rulings, posited that even when a developer "sells" exclusive usage rights for common elements, they are implicitly acting as an agent or mandatary for the entire body of unit owners (or the future management association). Consequently, under this theory, any proceeds from such "sales" should rightfully belong to the management association. The Supreme Court, however, prioritized the principle of contractual freedom and the actual, discernible intentions of the contracting parties. If the contracts clearly indicated that the developer was selling the rights for its own account, the Court was unwilling to impose an agency relationship by legal fiction.

3. Acknowledged Problems with the "Sale Model":

A critical takeaway, emphasized in both the main opinion and Justice Endo's supplementary opinion, is the Supreme Court's explicit acknowledgment that the practice of developers selling exclusive usage rights for common property is "not desirable." The reasons for this undesirability include:

- Potential for Unfairness and Double-Dipping: As Justice Endo detailed, it creates the appearance, and sometimes the reality, of the developer profiting twice from the land.

- Creation of Inequity Among Unit Owners: It can lead to disparities between unit owners who could afford or chose to buy these rights and those who could not, potentially creating different classes of owners concerning access to essential amenities.

- Source of Future Conflicts: The existence of these privately held rights over common elements often leads to long-term governance challenges and disputes within the condominium community.

4. Shift Towards a "Rental Model" under Management Association Control:

Recognizing the inherent problems with developers selling or retaining exclusive usage rights, there has been a significant and encouraged shift in Japan towards a "rental model." In this preferred model:

- The common area parking spaces remain fully under the control of the condominium management association.

- The association then leases these parking spaces to unit owners, typically based on rules set out in the condominium's bylaws.

- The rental income from these leases goes directly to the management association, benefiting all unit owners by contributing to the association's budget for maintenance, repairs, and other common expenses.

This shift has been supported by administrative guidance from government ministries (e.g., the then-Ministry of Construction, now Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism) and through amendments to standard management rules for condominiums. Legislative reforms, such as an amendment to the Condominium Ownership Act (Article 30, Paragraph 3) concerning the fairness of rules, also aim to provide a better framework for managing common elements equitably.

5. Legal Nature of Exclusive Usage Rights Remains Debated:

The Supreme Court, in this judgment, did not delve deeply into or definitively pronounce on the precise legal nature of these "exclusive usage rights" (専用使用権 - senyō shiyō ken). Various legal theories exist, such as whether they constitute a type of real right (物権的利用権説 - bukken teki riyōken setsu), a purely contractual (obligatory) right (債権的利用権説 - saiken teki riyōken setsu), or simply an agreement concerning the method of using common property (共有物の管理に関する合意説 - kyōyūbutsu no kanri ni kansuru gōi setsu). The Court's decision focused primarily on the contractual agreement for the sale of these rights and the attribution of the proceeds, rather than their fundamental legal classification. The rejection of the "developer as agent" theory was a key finding regarding the transaction itself.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's October 1998 decision provides a clear stance on the attribution of proceeds from the developer's sale of exclusive parking usage rights at the time of a condominium's initial offering. By prioritizing the contractual intent of the parties involved, the Court affirmed that these proceeds belong to the developer if the sale was conducted for the developer's own commercial account and was understood as such by the buyers.

However, the judgment, particularly when read alongside Justice Endo's supplementary opinion and other related rulings from the same period, also carries an important caveat: the sales method itself is fraught with problems and is not considered desirable. While upholding the validity of the specific contracts in this case, the decision implicitly supports the broader trend towards more equitable and less conflict-prone models, such as the management association controlling and leasing common area parking spaces. This landmark case thus highlights the tension between freedom of contract in initial sales and the long-term communal interests in condominium governance, underscoring the ongoing evolution of practices to better manage shared living spaces.