Parking Perks or Policy Problem? A Japanese Supreme Court Case on "Selling" Exclusive Use Rights in Condominiums

Date of Judgment: January 30, 1981

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, 1980 (O) No. 747 – Action for Declaratory Judgment of Non-Existence of Exclusive Parking Use Right

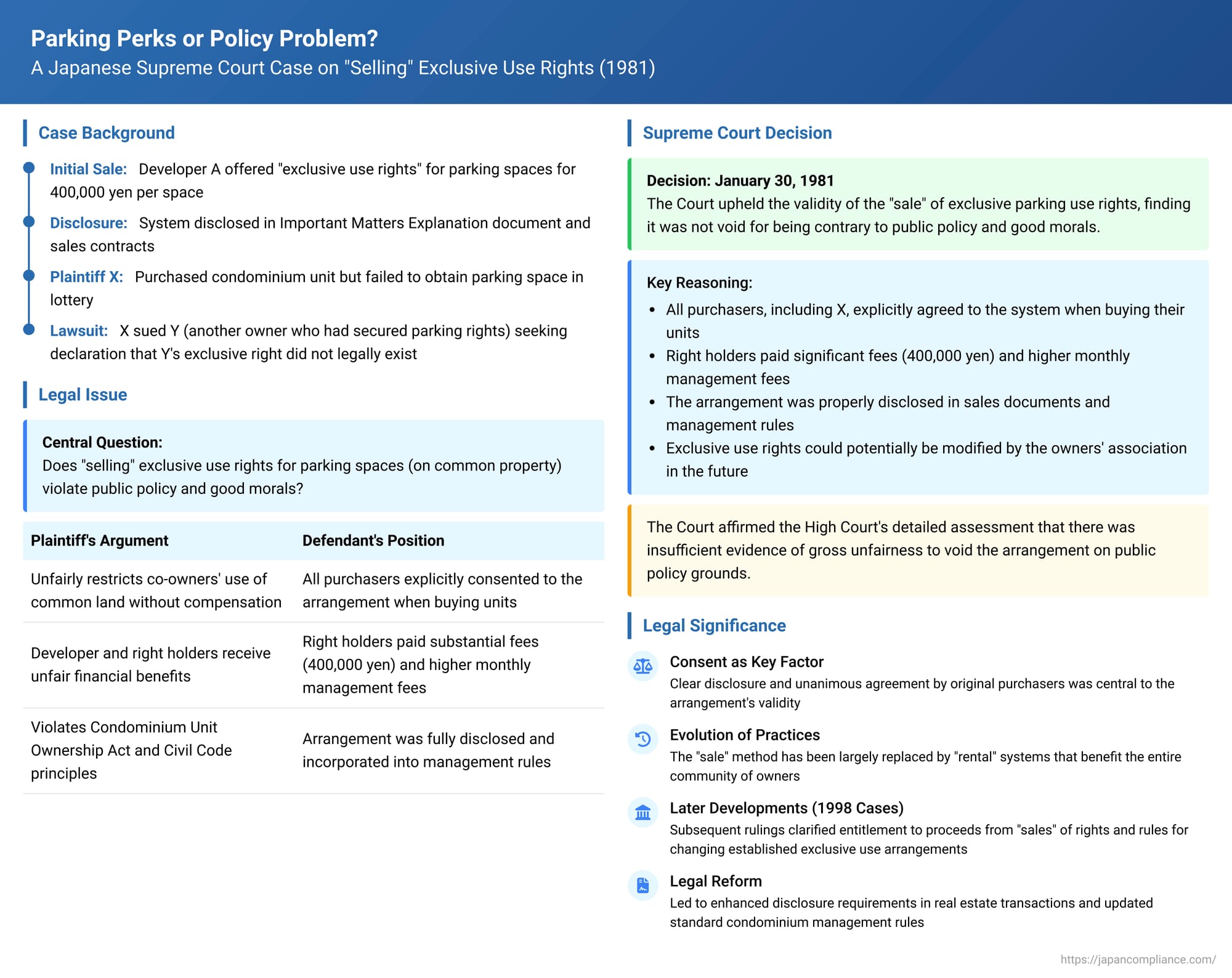

The allocation of parking spaces in condominium developments is a common source of interest and, at times, dispute among unit owners. Various methods have been employed by developers to manage this scarce resource, which is typically part of the common property. A Japanese Supreme Court decision from January 30, 1981, delved into the validity of a then-practiced method: the "sale" by the developer of exclusive use rights for parking spaces to condominium purchasers for a one-time fee. The case specifically addressed whether such an arrangement violated public policy and good morals.

The Arrangement: "Selling" Exclusive Parking Rights on Common Land

The dispute arose from a condominium project developed by "Developer A." As part of its sales process, Developer A established a parking area on a portion of the condominium site, which was designated as common property belonging to all unit purchasers. Instead of a rental system, Developer A offered "exclusive use rights" for individual parking spaces to interested condominium buyers. These rights were "sold" for a one-time payment of 400,000 yen per space. If the number of interested buyers exceeded the available spaces, a lottery was held to determine who would get the opportunity to purchase these rights.

This system was disclosed to prospective buyers. The details were included in the Important Matters Explanation document, a legally required disclosure under Japan's Real Estate Transaction Business Act, which was provided to and explained to applicants before they purchased their condominium units. Furthermore, the sales contracts signed by Developer A and each unit purchaser contained a specific clause: "The buyer acknowledges the exclusive use of the numbered and demarcated parking spaces on a portion of the land by those who have been sold such exclusive use rights by the seller, and by their assignees".

The condominium also had an owners' association (a self-governing body composed of all unit purchasers), and its management rules included provisions concerning the exclusive use of these parking spaces and the conditions for transferring such exclusive use rights. Notably, Mr. X, the plaintiff in this case, was one of the members of the committee that drafted these very management rules.

Mr. X had purchased a unit in the condominium but was unsuccessful in the lottery to obtain an exclusive use right for a parking space. He subsequently filed a lawsuit against Mr. Y, another unit owner who had successfully acquired such a right, seeking a court declaration that Mr. Y’s exclusive use right for his parking space did not legally exist. Mr. X's primary argument was that this "sale" of exclusive use rights by Developer A was contrary to public policy and good morals (kōjo ryōzoku). He contended that it unfairly restricted his (and other non-rightholding co-owners') use of commonly owned land without due compensation, while simultaneously allowing Developer A and the parking right holders like Mr. Y to derive significant financial benefits. He also alleged violations of the Condominium Unit Ownership Act and the Civil Code.

The Lower Courts' Defense of the Parking Scheme

The case progressed through the lower courts before reaching the Supreme Court:

- The Osaka District Court (judgment November 29, 1978) dismissed Mr. X’s claim. While acknowledging that Developer A’s "sale" method for parking rights might not be the most desirable approach, it found insufficient grounds to declare it void as against public policy. The District Court reasoned that the exclusive use rights were not necessarily permanent and could potentially be abolished or modified by the owners' association through amendments to the management rules or by applying general principles of co-owned property management if the rules were silent on such changes.

- The Osaka High Court (judgment April 25, 1980) also dismissed Mr. X’s appeal, providing a more detailed rebuttal to his legal arguments:

- Applicability of the Condominium Unit Ownership Act: The High Court found it difficult to extend the Act's provisions governing the management of common areas within the building to the management of the condominium site (land), which it viewed as distinct real estate.

- Violation of Civil Code Article 251 (Changes to Co-owned Property): Mr. X argued that setting up exclusive use rights constituted a "change to common property" requiring the unanimous consent of all co-owners. The High Court doubted that creating such parking rights clearly fell under this category. More importantly, it held that even if it did, all purchasers, by signing sales contracts that explicitly acknowledged and accepted the system of reserved exclusive parking use rights, had effectively given their prior consent to this arrangement.

- Developer’s Alleged "Double Profit": The High Court rejected the assertion that Developer A was unfairly profiting twice. It suggested that it was plausible for the developer to have structured its overall financial plan for the condominium project by treating the sale of the condominium units and the sale of parking use rights as separate but related revenue streams, factoring both into its comprehensive income and expenditure calculations. Thus, it could not be summarily concluded that this constituted a "double profit". The court also found that the arrangement did not amount to an adhesion contract.

- Unfairness to Non-Rightholders (Paying Property Taxes but Lacking Use): Mr. X complained about the inequity of co-owning the land and paying property taxes on it while being unable to use the portions designated for exclusive parking. The High Court likened this situation to acquiring ownership of land that is already burdened by a third-party right, such as a leasehold or other land use right, a circumstance that would have been foreseeable at the time of signing the purchase contract. Furthermore, it noted that those who acquired exclusive parking use rights had paid a significant one-time fee of 400,000 yen and also contributed approximately 500 yen more per month in management fees compared to those without such rights, which mitigated any perceived inequality. While acknowledging that by 1980 (and since 1974) rental methods for parking allocation had become more common, the High Court concluded that this fact alone did not render the "sale" method employed in this earlier development automatically contrary to public policy.

Mr. X appealed the High Court’s decision to the Supreme Court, focusing his appeal solely on the argument that the parking rights agreement violated public policy and good morals.

The Supreme Court's Concise Affirmation

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of January 30, 1981, dismissed Mr. X’s appeal. The judgment was notably brief. The Court stated that it found the High Court’s determination of the facts to be appropriate and justifiable based on the evidence presented and the reasoning articulated in the High Court's decision. Consequently, the Supreme Court affirmed the High Court’s ultimate conclusion: under the established facts of this case, the agreement between the condominium purchasers and Developer A concerning the establishment of exclusive parking use rights was not void for being contrary to public policy and good morals.

Exclusive Use Rights and Public Policy Considerations

An "exclusive use right" (sen'yō shiyō ken) in the condominium context grants a specific unit owner the right to use a designated part of the common area (like a parking space, balcony, or garden patch) to the exclusion of other unit owners. The core of Mr. X’s public policy argument was that such an arrangement, when "sold" by the developer, unjustly enriched the developer and the right-holding purchasers while unfairly limiting the property rights of other co-owners who did not secure such rights.

The High Court’s reasoning, endorsed by the Supreme Court, countered this by emphasizing several key elements:

- Prior Consent of All Purchasers: A crucial factor was that all initial condominium purchasers, including Mr. X, had explicitly agreed to this system of exclusive parking rights when they bought their units. This consent was evidenced by the Important Matters Explanation, the clauses in the sales contracts, and the management association rules (which Mr. X himself had a hand in drafting).

- No Gross Imbalance or Unfairness: The financial aspects were considered. Those who obtained parking rights paid a substantial one-time fee (400,000 yen) and also bore slightly higher monthly management fees. This offset the benefit of exclusive use and addressed, to some extent, the concern about unequal burdens and benefits among co-owners.

- Potential for Future Modification: The District Court had noted, and this likely influenced the higher courts, that such exclusive use rights established by initial agreement were not necessarily immutable or permanent. The owners' association, through its governance mechanisms (like amending management rules by qualified majority vote), could potentially alter or even abolish these parking arrangements in the future, subject to legal limitations protecting acquired rights or addressing "special impacts" on affected owners.

Legal commentary on this topic clarifies that exclusive use rights over common areas in a condominium are typically established either by the unanimous agreement of all co-owners at the time the condominium regime is formed (as was effectively the case here through the initial sales process) or subsequently through the condominium's management rules or by resolutions passed at general meetings of the owners' association.

The Evolution of Parking Allocation and Later Legal Developments

It's important to view this 1981 Supreme Court decision in its historical context. The commentary accompanying the case notes that the "sale" or "assignment method" (jōto hōshiki) for parking rights, as employed by Developer A, is now rarely used in Japan. The more prevalent approach today is the "rental method" (chintai hōshiki). Under this model, the condominium management association typically leases the parking spaces to unit owners, and the rental income generated is incorporated into the association's budget to cover common maintenance expenses and build up repair reserves. This rental model is generally seen as aligning more closely with the principle that common property should be managed for the benefit of all co-owners.

The commentary also points to several later Supreme Court decisions from 1998 (Heisei 10) that further clarified related legal issues:

- Entitlement to Proceeds from "Sale" of Rights: One line of cases (e.g., the "Million Corporus Kōhō-kan" case, Sup. Ct. Oct. 22, 1998, and the "Charme Tamachi" case, Sup. Ct. Oct. 30, 1998) addressed who is entitled to the funds received by a developer from "selling" such exclusive use rights. The Supreme Court generally held that if the developer structured the initial condominium offering with the intent to sell these rights for its own profit, and the buyers were aware of this arrangement, then the proceeds belong to the developer, not to the collective of unit owners or the management association. The courts rejected the idea of treating the developer as an agent acting on behalf of all unit owners in these sales.

- Disputes Among Unit Owners: Another set of 1998 rulings (e.g., the "Charmant Corpor 博多" case, Sup. Ct. Oct. 30, 1998, and the "Takashimadaira Mansion" case, Sup. Ct. Nov. 20, 1998) dealt with disputes arising when management associations attempted to change parking fee structures or abolish existing exclusive use rights through amendments to the management rules. These cases explored the concept of "special impact" under Article 31 of the Condominium Unit Ownership Act, which requires the consent of an affected unit owner if a change in rules would disproportionately prejudice their rights. The Court established a balancing test, weighing the necessity and reasonableness of the rule change against the detriment suffered by the individual owner.

Lessons and Current Practices

While the Supreme Court in 1981 upheld the specific "sale" method for parking rights in this case, largely due to the clear disclosures and unanimous initial consent, the legal landscape and common practices have evolved:

- The shift towards rental models managed by the owners' association reflects a greater emphasis on common benefit and equitable sharing of common property resources.

- The case underscores the enduring importance of full disclosure by developers and informed consent by purchasers for any arrangements that grant exclusive rights over common areas.

- The commentary raises a pertinent question about the level of understanding first-time condominium buyers in that era had regarding complex legal concepts like "exclusive use rights". This highlights the ongoing need for clear and comprehensible explanations from sellers.

- Subsequent amendments to the Real Estate Transaction Business Act and its enforcement regulations now mandate more specific disclosures regarding rights related to common areas, the content of management rules, and any arrangements for specific individuals to exclusively use parts of the common property. Standard condominium management rules have also been updated over the years to reflect a preference for rental systems for parking.

Conclusion: Consent as Key in an Evolving Landscape

The 1981 Supreme Court decision affirmed the validity of a developer-led "sale" of exclusive parking use rights primarily because the arrangement was clearly disclosed and agreed to by all original purchasers, and it was not deemed grossly unfair or contrary to public policy at the time. However, the evolution of condominium practices and subsequent legal refinements indicate a broader trend towards managing common assets like parking spaces in a way that more directly benefits the entire community of unit owners, typically through rental systems administered by the management association. This case, while upholding a specific historical practice based on consent, serves as a valuable reference point in understanding the legal principles governing the use and allocation of common areas in Japanese condominiums and the importance of transparency in such dealings.