Parent Company Director Liability in Japan: Oversight of Subsidiary Compliance Failures

TL;DR

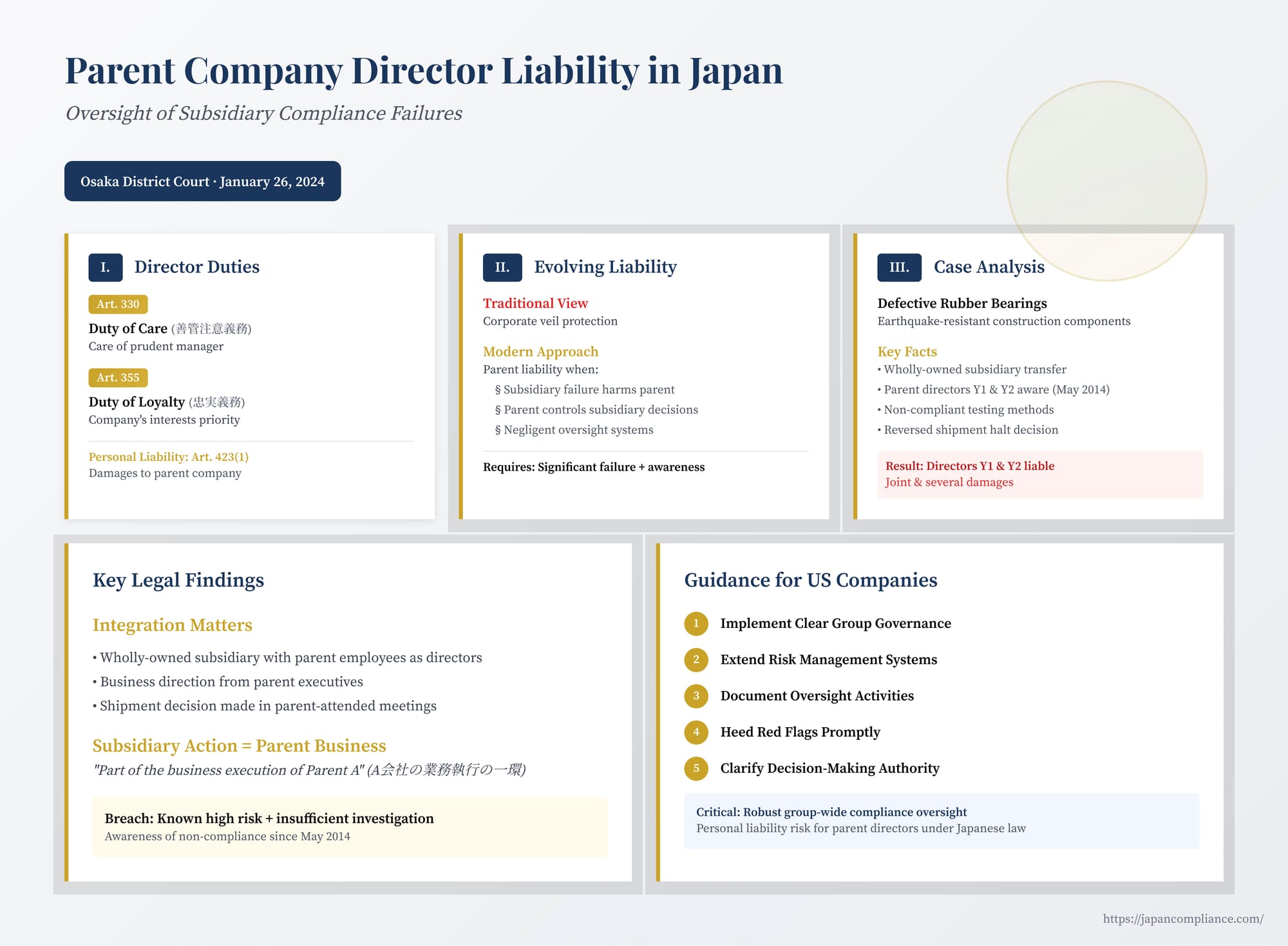

- Japanese courts now scrutinise parent-company directors who ignore “red flags” of subsidiary misconduct—finding possible liability under Companies Act Articles 355 & 423.

- Key risks include derivative suits, loss-recovery actions and criminal aiding-and-abetting if directors fail to implement adequate group-wide compliance systems.

- Multinationals must formalise reporting lines, conduct risk-based monitoring and document board deliberations to defend the business-judgment rule.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Why Subsidiary Misconduct Becomes a Parent Problem

- Legal Framework: Directors’ Duty of Care and Oversight (Companies Act)

- Recent Case Law on Parent Oversight Failures (Tokyo District Court, 2024)

- When Can a Parent Director Be Sued?

- Best-Practice Oversight Mechanisms for Global Groups

- Implications for US-Headquartered Multinationals

- Conclusion

For US corporations expanding globally, establishing local subsidiaries is a common and often necessary strategy. When operating in Japan through a subsidiary structure, however, parent company directors and executives need to be aware of the potential legal risks associated with overseeing those subsidiary operations. While a subsidiary is a distinct legal entity, failures at the subsidiary level – particularly concerning legal compliance and product safety – can sometimes lead to liability risks for the directors of the parent company under Japanese law.

A recent court decision from the Osaka District Court (January 26, 2024) sheds light on the circumstances under which parent company directors can be held liable for damages incurred by the parent due to compliance failures within a wholly-owned subsidiary. This case underscores the importance of robust group governance and effective oversight mechanisms for multinational corporations with Japanese operations.

Parent Company Director Duties Under Japanese Company Law

Directors of Japanese corporations, including parent companies, owe fiduciary duties primarily to their own company. Key duties under the Japanese Companies Act include:

- Duty of Care (善管注意義務 - zenkan chūi gimu): Directors have a duty to manage the company's affairs with the care of a prudent manager. This duty is derived from the mandate relationship between the director and the company (Companies Act Art. 330, applying Civil Code Art. 644). It requires directors to be reasonably informed and act diligently in making business decisions and overseeing operations.

- Duty of Loyalty (忠実義務 - chūjitsu gimu): Directors must perform their duties loyally for the benefit of the company (Companies Act Art. 355). This prohibits self-dealing and requires directors to prioritize the company's interests over their own or those of third parties.

If directors breach these duties, either through action or inaction (neglect of duties), and cause damage to their company (the parent company, in this context), they can be held personally liable to compensate the company for those damages (Companies Act Art. 423, Paragraph 1). This liability is typically enforced through shareholder derivative lawsuits brought on behalf of the company.

The Evolving Landscape: Parent Liability for Subsidiary Oversight

Traditionally, the corporate veil provides separation – directors of a parent company are not automatically liable for the mismanagement or torts of a legally distinct subsidiary. Their duty of care is owed to the parent, not directly to the subsidiary or its creditors.

However, legal scholarship and developing case law in Japan, as in other jurisdictions, recognize that a parent company director's duty of care to the parent can encompass the duty to establish adequate systems for overseeing subsidiary operations, particularly when the subsidiary's activities pose significant risks to the parent company itself. Liability might arise for parent directors if:

- Subsidiary Failure Causes Direct Harm to the Parent: The subsidiary's mismanagement, compliance failure, or illegal act directly causes financial or reputational damage to the parent company (e.g., parent needing to fund subsidiary bailouts, pay damages under guarantees, or suffering brand damage affecting the parent's own business), AND this damage resulted from the parent directors' negligent failure to establish proper group governance or risk management systems, or failure to act upon known red flags concerning the subsidiary.

- Parent Directors Effectively Control Subsidiary Decisions: In closely integrated corporate groups, especially involving wholly-owned subsidiaries, if parent company directors effectively dominate the subsidiary's decision-making process regarding the specific action that caused harm, courts might, in certain circumstances, view the subsidiary's action as substantively part of the parent's own business execution, potentially leading to liability for the parent directors involved in that decision.

Establishing parent director liability for subsidiary oversight failures remains challenging. Courts generally require a showing of significant failure, often involving awareness of serious risks or gross negligence in oversight, rather than simple errors in judgment regarding subsidiary management.

Case Study: Defective Products and Parent Director Liability (Osaka Dist. Ct., Jan 26, 2024)

The Osaka District Court case provides a concrete example where parent director liability was affirmed.

Scenario

(Based on the facts reported in the case note, anonymized): A large Japanese manufacturing company ("Parent A") operated several business divisions. Some years prior, it established a wholly-owned subsidiary ("Subsidiary B") by transferring its business division responsible for manufacturing specialized construction components, specifically earthquake-resistant laminated rubber bearings. Personnel also moved from the parent division to the subsidiary.

Parent A directors retained oversight. Director Y1 was the head of the parent's broader business division encompassing Subsidiary B's operations and effectively supervised the subsidiary. Director Y2 was the head of the parent's technical center, responsible for quality control across related products.

In mid-2014, Parent A directors Y1 and Y2 became aware of potential serious issues: Subsidiary B might be using technically unfounded testing methods for certain rubber bearings, potentially meaning products shipped did not meet mandatory technical standards under Japan's Building Standards Act. Investigations were ordered. By September 2014, despite internal meetings confirming problems and an initial decision to halt shipments of a specific product model (G0.39), a subsequent internal report suggested that applying certain "corrections" to test data could make the products appear compliant. In a meeting attended by Parent directors Y1 and Y2, the decision was made to reverse the shipment halt, and Subsidiary B proceeded to ship the potentially non-compliant products ("Subject Shipments") to a construction company ("Company C") for use in a building project for a customer ("Customer D").

Later investigations confirmed the testing methods lacked technical basis. Parent A ultimately reported the issue to the relevant ministry (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism) in early 2015. Parent A subsequently entered into agreements with Customer D and Company C to cover costs related to replacing the defective products and compensating for construction delays.

A shareholder of Parent A ("Shareholder X") filed a derivative lawsuit against four Parent A directors (Y1, Y2, Y3 [President], and Y4 [Compliance Officer]), alleging they breached their duty of care by failing to prevent the Subject Shipments and by delaying reporting the issue to authorities, causing damage to Parent A (the costs paid to Customer D and Company C).

Court's Key Findings on Director Liability for Shipment Decision

The Osaka District Court found Directors Y1 and Y2 liable for damages related to the improper shipment decision (liability for delayed reporting was also found against all four, but is not the focus here). The court's reasoning involved several key steps:

- Close Integration and Parent Control: The court looked beyond the separate legal personalities of Parent A and Subsidiary B. It highlighted that Subsidiary B was wholly-owned, established by transferring a Parent A division, had Parent A employees serving as its directors, was organizationally positioned within Parent A's divisional structure, and received business direction from Parent A executives (including Y1). Critically, the decision whether to ship the potentially non-compliant products manufactured by Subsidiary B was made in meetings attended and influenced by Parent A directors Y1 and Y2, based on reports submitted to Parent A.

- Subsidiary Action as Parent's Business Execution: Based on this high degree of integration and parental control over the specific decision, the court concluded that the decision regarding the Subject Shipments, although executed by Subsidiary B, should be considered "part of the business execution of Parent A" (A会社の業務執行の一環 - A kaisha no gyōmu shikkō no ikkan). This finding was crucial for establishing the relevance of the parent directors' duties.

- Breach of Duty of Care (Directors Y1 & Y2): The court found that Directors Y1 (as head of the supervising division) and Y2 (as head of technical/quality assurance) owed a duty of care to Parent A regarding the decision to allow the Subject Shipments. They were aware, from May 2014 onwards, of significant doubts about the product's compliance with mandatory technical standards. Despite an initial correct decision to halt shipments, they reversed this based on internal reports suggesting data "corrections" could achieve compliance, without sufficiently verifying the technical validity of those corrections. By allowing shipments under these circumstances of known high risk and insufficient investigation, they breached their duty of care.

- Liability for Damages: The court held Y1 and Y2 jointly and severally liable under Companies Act Article 423(1) for the damages suffered by Parent A as a direct result of this breach. These damages included the costs Parent A paid for product replacement (repair work) and compensation for project delays and related personnel costs incurred due to the compliance failure, as formalized in the agreements with Customer D and Company C. (Directors Y3 and Y4 were not found liable specifically for the shipment decision itself, likely due to differing levels of involvement or knowledge at that specific point).

Analysis and Implications

This Osaka District Court decision, while a first-instance ruling, provides important clarifications and warnings:

- Parent Director Liability is Real: It confirms that parent company directors can be held personally liable in derivative suits for damages suffered by the parent company stemming from mismanagement or compliance failures at the subsidiary level, particularly in cases involving wholly-owned and closely integrated subsidiaries.

- Integration Matters: The court placed significant weight on the operational and managerial integration between the parent and subsidiary. Where a subsidiary functions essentially as an operating division under direct parent control, the actions taken regarding that subsidiary's business are more likely to be viewed as falling within the scope of the parent directors' oversight duties to the parent.

- Awareness and Action are Key: Liability attached to the directors (Y1, Y2) who were directly involved in the relevant business line and quality control, were aware of the specific risks of non-compliance, and participated in the flawed decision to proceed with shipments despite those risks. This suggests liability is less likely for parent directors who are further removed, unless they demonstrably failed to act on red flags reported up to them or failed to ensure adequate group-wide risk management systems were in place.

- Importance of Group Governance: The case underscores the critical need for robust governance frameworks within corporate groups. This includes clear reporting lines, effective risk management systems that cover subsidiary operations, mechanisms for escalating significant issues from subsidiaries to the parent board, and clear protocols for investigating and addressing compliance concerns, regardless of where in the group structure they arise.

- Focus on Harm to the Parent: The liability under Article 423 is for damage caused to the parent company. In this case, Parent A directly incurred the costs of remediation and compensation. The case note points out that even if Subsidiary B had borne these costs initially, Parent A (as the sole shareholder) would likely still have suffered an equivalent loss through the diminution in value of its subsidiary investment, potentially allowing a similar claim based on established Supreme Court precedent regarding damage to wholly-owned subsidiaries (Sup. Ct. Sep 9, 1993, Minshu 47-7-4814).

Guidance for US Parent Companies and Directors

For US corporations with Japanese subsidiaries, this case serves as a reminder of potential oversight liability risks under Japanese law. Practical steps to mitigate these risks include:

- Implement Clear Group Governance: Establish clear group-wide policies, reporting structures, and defined responsibilities for subsidiary oversight. Ensure reporting lines allow critical information (especially regarding compliance and significant risks) to reach the relevant parent company executives and board members.

- Extend Risk Management: Ensure group-level risk management and internal control systems adequately cover material risks within Japanese subsidiaries. This is particularly important for regulated industries, product safety, environmental compliance, and anti-corruption.

- Document Oversight: Parent directors and relevant executives should maintain records demonstrating their oversight activities related to significant subsidiary matters (e.g., review of subsidiary reports, board discussions, inquiries made).

- Heed Red Flags: Establish processes to identify and escalate red flags from subsidiary operations. Parent directors who become aware of serious compliance risks or potential illegalities at the subsidiary level have a duty to inquire further and ensure appropriate action is taken. Ignoring known risks is a key factor leading to liability.

- Clarify Decision-Making Authority: While integration can be efficient, clearly delineating decision-making authority between parent and subsidiary management for key operational and compliance matters can help manage liability exposure, provided overall oversight is maintained.

- Seek Local Expertise: Ensure that both the subsidiary and the parent have access to qualified Japanese legal counsel to advise on compliance with local laws and regulations and on structuring effective group governance.

Conclusion

The Osaka District Court's decision reaffirms that while Japanese law respects the separate legal entity status of subsidiaries, it does not provide absolute immunity for parent company directors from liability related to subsidiary failures. Where a subsidiary is closely integrated and controlled, and parent directors are aware of significant compliance risks but fail to exercise due care in addressing them, they can be held personally liable for the resulting damages suffered by the parent company. This highlights the crucial importance for US corporations to implement and diligently maintain robust group-wide governance and risk management systems that effectively oversee the operations and compliance of their Japanese subsidiaries. Failure to do so not only exposes the parent company to financial and reputational harm but also creates tangible personal liability risks for its directors under Japanese law.

- Director Liability and Corporate Donations in Japan: Balancing Philanthropy and Fiduciary Duty

- Shareholder Activism in Japan: The Rise of Derivative Lawsuits and Director Liability

- Mandatory Sustainability Reporting in Japan: FIEA Rules & ISSB Alignment for Global Companies

- FSA Corporate Governance Code – 2021 Revision (PDF)

- METI “Group Governance” Study Report (Japanese)