Parallel Imports in Japan: The Supreme Court's Fred Perry Test for Genuine Goods

Judgment Date: February 27, 2003

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Case Number: Heisei 14 (Ju) No. 1100 (Damages, Trademark Infringement Injunction, etc. Claim)

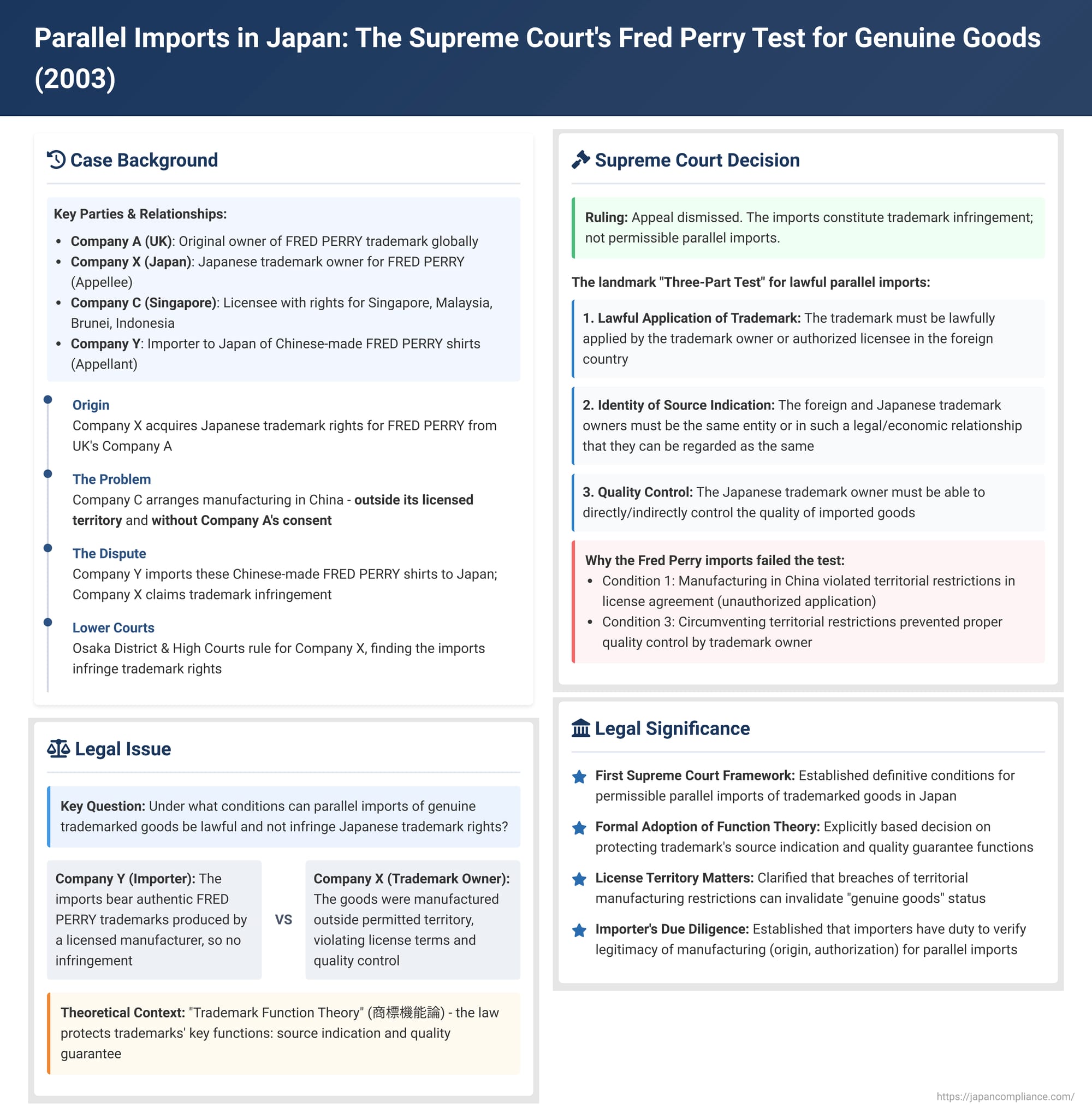

The "Fred Perry" case, decided by the Japanese Supreme Court in 2003, is a landmark ruling that established a clear three-part test for determining when the parallel importation of goods bearing a genuine trademark does not constitute trademark infringement in Japan. This judgment is pivotal as it was the Supreme Court's first comprehensive pronouncement on the issue, grounding its decision in the "trademark function theory" and emphasizing the importance of both the source indication and quality guarantee functions of trademarks.

The Fred Perry Scenario: A Complex Web of International Licensing and Unauthorized Production

The factual background of the case involved an intricate international licensing and manufacturing arrangement for "FRED PERRY" branded apparel.

- The Trademarks and Japanese Rights: Company X (the appellee before the Supreme Court) held the Japanese trademark rights ("Japanese TM Rights") for two well-known "FRED PERRY" marks – one consisting of the words "FRED PERRY" and the other featuring the iconic laurel wreath device. These rights covered clothing and related goods. Company X had acquired these Japanese TM Rights from Company A, a UK-based corporation that was the original owner of the Fred Perry trademarks and held rights in approximately 110 countries worldwide.

- The Importer and the Disputed Goods: Company Y (the appellant before the Supreme Court) imported into Japan polo shirts bearing the same Fred Perry trademarks ("Imported Goods"). These shirts were manufactured in the People's Republic of China.

- The Licensing Agreement and its Breach: The manufacturing of these Imported Goods was arranged by Company C, a Singaporean company. Company C had a license agreement with Company A (the original UK trademark owner) to manufacture and sell Fred Perry branded products in specific territories: Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia. However, the crucial issue was that Company C had these particular Imported Goods manufactured in China – a territory outside its contractual license – and did so without the consent of Company A. This action constituted a breach of the manufacturing location restrictions stipulated in its license agreement with Company A.

- The Legal Dispute: Company X, as the Japanese trademark owner, considered the Imported Goods to be infringing and took action, including placing an advertisement in an industry newspaper published by Company Z, asserting that the Imported Goods were counterfeit. This led to Company Y suing Company X and Company Z for damages and a published apology, claiming business interference and harm to its credit. Company X, in turn, counter-sued Company Y for trademark infringement, seeking an injunction against the importation and sale of the Imported Goods, as well as damages and an apology.

The lower courts (Osaka District Court and Osaka High Court) sided with Company X, ruling that Company Y's importation of the Chinese-made polo shirts did not qualify as permissible parallel importation of genuine goods. They found that this activity infringed Company X's Japanese TM Rights and dismissed Company Y's claims. Company Y then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Three-Pronged Test for Lawful Parallel Importation

The Supreme Court dismissed Company Y's appeal, thereby affirming the lower courts' decisions. In its judgment, the Court laid out a definitive three-part test to determine when the importation of goods bearing a genuine trademark, which would otherwise constitute trademark infringement, lacks "substantive illegality" (実質的違法性 - jisshitsuteki ihōsei) and is therefore permissible.

The Court first acknowledged the basic principle: importing goods that are identical to those covered by a Japanese trademark registration and that bear an identical trademark, without the authorization of the Japanese trademark owner, prima facie infringes the Japanese trademark right (as per Trademark Law Article 2, Paragraph 3 and Article 25).

However, the Court then established that such importation will not be considered infringing if all of the following three conditions are met:

- Lawful Application of the Trademark Abroad: The trademark on the imported goods must have been lawfully applied by the trademark owner in the foreign country or by a licensee duly authorized by that foreign trademark owner. This condition pertains to the legitimacy of the mark's affixation at its origin.

- Identity of Source Indication: The trademark owner in the foreign country and the Japanese trademark owner must either be the same entity or be in such a legal or economic relationship that they can be regarded as the same entity. This ensures that the trademark on the imported goods indicates the same source as the Japanese registered trademark.

- Quality Control and Substantial Sameness: The Japanese trademark owner must be in a position to directly or indirectly control the quality of the imported goods. Consequently, the imported goods and the goods sold by the Japanese trademark owner under the registered trademark must be evaluable as having no substantial difference in the quality guaranteed by that registered trademark.

Rationale for the Three-Part Test: The Trademark Function Theory

The Supreme Court explicitly grounded this three-part test in the "trademark function theory" (商標機能論 - shōhyō kinōron). It cited Article 1 of the Trademark Law, which states that the law aims "to protect trademarks, thereby contributing to the maintenance of the business goodwill of persons who use trademarks, and thereby to contribute to the development of industry and to protect the interests of consumers".

The Court reasoned that if the parallel importation of so-called "genuine goods" (真正商品 - shinsei shōhin) satisfies all three conditions outlined above, it will not harm the essential functions of a trademark, namely:

- The source indication function (出所表示機能 - shussho hyōji kinō).

- The quality guarantee function (品質保証機能 - hinshitsu hoshō kinō).

When these functions are not impaired, the importation does not harm the business goodwill of the trademark user or the legitimate interests of consumers, and thus, it lacks substantive illegality.

Why Fred Perry's Chinese-Made Polo Shirts Failed the Test

Applying this newly articulated three-part test to the facts of the Fred Perry case, the Supreme Court found that the importation of the polo shirts manufactured in China did not meet the criteria for permissible parallel importation:

- Failure of Condition (1) - Lawfully Applied Trademark: The Imported Goods were manufactured under the instruction of Company C, which was indeed a licensee of Company A (the original global trademark owner). However, this manufacturing took place in China, a territory outside the scope of Company C's license agreement, and crucially, without the consent of the trademark owner (Company A) for such out-of-territory production. The affixation of the Fred Perry trademark to these goods, having been done in contravention of the license terms regarding manufacturing location, was deemed to be outside the scope of the license granted. The Court concluded that this harmed the source indication function of the trademark. The mark, in this context, did not genuinely represent an authorized product from the licensed source under the agreed conditions.

- Failure of Condition (3) - Quality Control and Substantial Sameness: The license agreement between Company A and Company C contained specific restrictions on the country of manufacture and on subcontracting. The Supreme Court highlighted that such restrictions are "extremely important for the trademark owner to control the quality of the products and fully ensure the quality guarantee function". Because the Imported Goods were manufactured in violation of these critical restrictions, they were "not subject to the trademark owner's quality control". This created a "possibility of substantial differences in quality" between these Imported Goods and the authentic goods legitimately distributed by Company X (the Japanese trademark owner) under the Fred Perry trademark in Japan. This situation, the Court found, posed a threat to the quality guarantee function of the trademark.

Consequences of Failing the Test:

The Court reasoned that allowing the importation of goods produced under such circumstances would:

- Risk damaging the business goodwill that Company A and Company X had diligently built for the "Fred Perry" brand.

- Betray consumer trust, as consumers generally expect parallel imports to be identical in source and quality to the goods sold by the official Japanese trademark owner or distributor.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that the importation of these specific Fred Perry polo shirts did not qualify as permissible parallel importation of genuine goods because it failed to satisfy conditions (1) and (3) of its test. As a result, the act of importation could not be said to lack substantive illegality and thus constituted an infringement of Company X's Japanese trademark rights.

Importer's Duty of Care (Negligence):

The Court also briefly touched upon the issue of negligence on the part of the importer, Company Y. It noted that customs law requires importers to declare the manufacturing origin of goods. When importing goods bearing a trademark identical to a Japanese registered mark, especially if those goods are sourced from a foreign licensee rather than directly from the foreign trademark owner, the importer has a duty. This duty involves, at a minimum, confirming that the licensee possessed the proper authority under its license agreement to manufacture the goods in that specific country and to affix the trademark there. Company Y had not provided evidence that it had fulfilled this duty of care in verifying the legitimacy of the Chinese-manufactured goods. Therefore, the presumption of negligence (under Patent Law Article 103, which is applied mutatis mutandis to trademarks via Trademark Law Article 39) was not overturned.

Deeper Dive into the Significance of the Fred Perry Ruling

The Fred Perry Supreme Court decision is a landmark for several reasons:

- First Supreme Court Clarification on Parallel Imports: It was the Supreme Court's first comprehensive judgment establishing the specific conditions under which parallel importation of trademarked goods is considered lawful in Japan. This provided much-needed clarity for businesses involved in international trade.

- Formal Adoption of Trademark Function Theory at the Highest Level: The ruling explicitly embraced the "trademark function theory" as the basis for its decision. This theory, which had been influential in earlier lower court decisions (such as the "Parker Pen" case, Osaka District Court, 1970) and in customs administration, posits that acts which formally fall within the scope of a trademark right may nevertheless be permissible if they do not harm the essential functions of the trademark.

- Identification of Protected Trademark Functions: The Supreme Court identified the source indication function and the quality guarantee function as the key functions protected by trademark law in the context of parallel imports. While other functions like advertising are sometimes discussed, the Court focused on these two as critical for determining the legality of parallel imports. The extent to which the quality guarantee function should be protected had previously been a point of significant debate among legal scholars and in lower court rulings.

- Emphasis on the Trademark Owner's Ability to Control Quality: A particularly noteworthy aspect of Condition (3) is its emphasis on the Japanese trademark owner's ability to directly or indirectly control the quality of the imported goods. This shifted the focus somewhat from previous lower court approaches that often centered on whether there were objective, demonstrable differences in quality between the parallel imports and the locally distributed goods. The Supreme Court's formulation suggests that if the trademark owner's quality control mechanisms are bypassed or compromised—as happened in this case due to unauthorized out-of-territory manufacturing—this condition might not be met, even if the specific batch of imported goods coincidentally happened to be of identical physical quality to the "official" goods. The potential for quality variance due to lack of authorized control appeared sufficient.

- Clarification on Breaches of License Agreements: The case provided important guidance on the impact of a foreign licensee breaching its license agreement with the trademark owner.

- The Court found that manufacturing goods outside the contractually agreed territory and without the trademark owner's specific consent for that manufacturing activity (a breach of Condition (1)) directly harmed the source indication function. This implies that the "genuineness" of a product for parallel import purposes is not solely about whether the mark was initially authorized in a general sense by the global trademark owner, but also whether it was applied in accordance with the specific terms of authorization relevant to the goods in question.

- The commentary in the provided source suggests that not all breaches of a license agreement would necessarily lead to the same outcome. For instance, a licensee's failure to pay royalties might not, in itself, impair the source indication or quality guarantee functions of the trademark on the products already manufactured under license. However, breaches of terms directly linked to the integrity of the product or the brand, such as manufacturing location restrictions designed for quality oversight, are treated more severely. The precise impact of breaching other types of clauses, like sales territory restrictions or pricing clauses, remains a subject for ongoing legal development.

Implications for Businesses

The Fred Perry ruling has significant practical implications:

- For Trademark Owners: It strengthens their ability to control the quality and sourcing of goods bearing their trademarks that enter the Japanese market, even if those goods originate from their international licensing network. It underscores the importance of carefully drafted license agreements with clear stipulations regarding manufacturing locations, subcontracting, and quality control processes.

- For Parallel Importers: It imposes a greater due diligence burden. Importers cannot simply assume that goods bearing a famous brand, if sourced from an overseas licensee, are automatically "genuine" for the purposes of lawful parallel importation into Japan. They need to be vigilant in ensuring that the goods were produced and the trademark affixed in full compliance with the terms of the original licensing authorization, particularly concerning aspects that could affect source integrity and quality control by the ultimate trademark owner.

Conclusion

The Fred Perry Supreme Court decision is a cornerstone of Japanese law on parallel importation. By establishing a clear, function-based three-part test, it provides a robust framework for balancing the principles of free trade with the essential rights of trademark owners to protect their brand's goodwill, which is inextricably linked to source identity and quality assurance. The ruling emphasizes that "genuine goods" for the purpose of permissible parallel importation are not merely those that bear an authentic trademark, but those that also respect the trademark owner's legitimate control over how and where that mark is applied, particularly concerning quality. This ensures that both the business reputation of the trademark holder and the trust of consumers are adequately safeguarded in the Japanese market.