Parallel Imports and Patent Rights: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Territoriality and Implied License

Date of Judgment: July 1, 1997

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

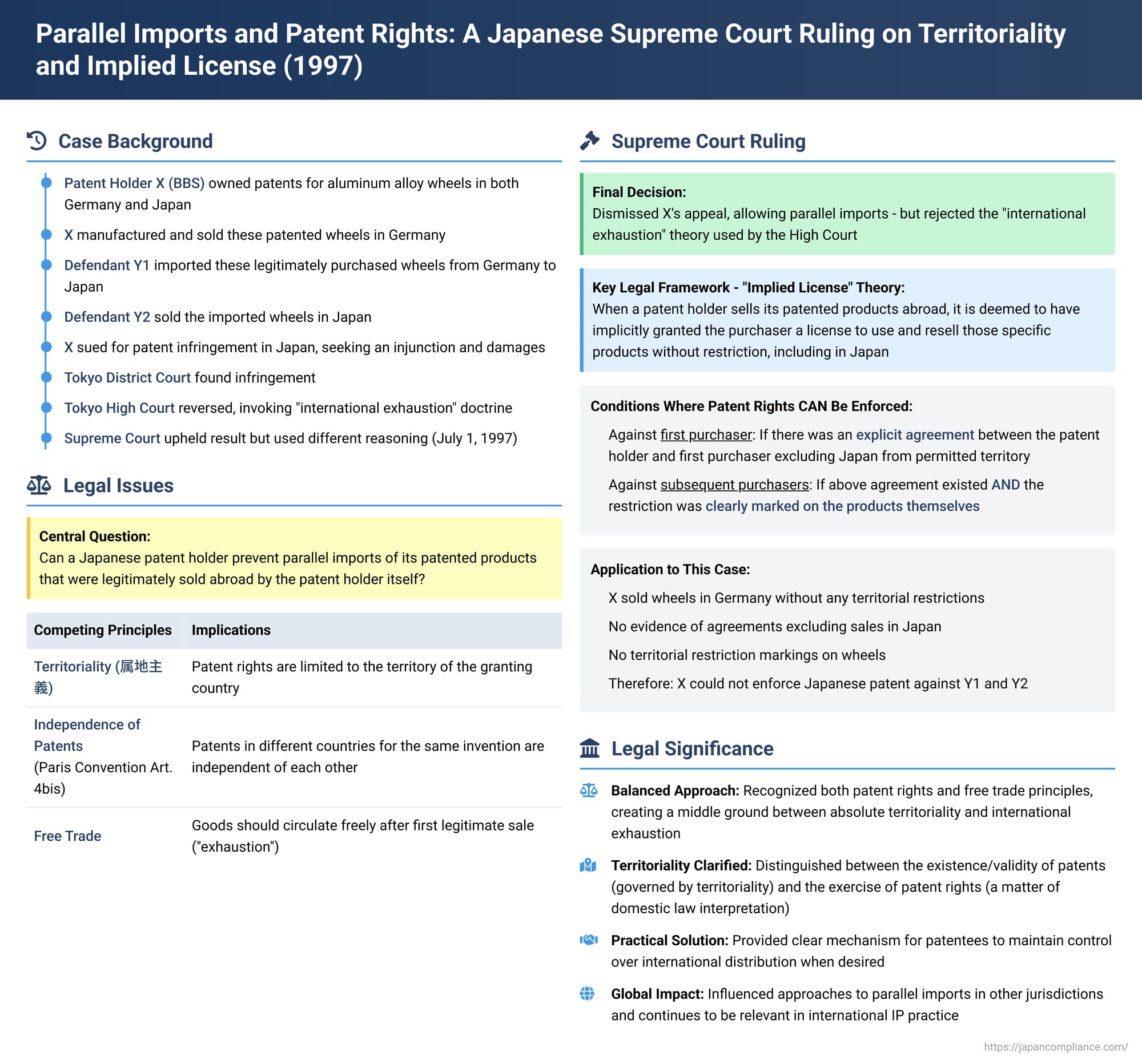

The globalized marketplace often sees patented products, legitimately sold in one country, being imported into another country where a corresponding patent exists, without the patent holder's direct authorization for that specific importation. This practice, known as "parallel importation," creates a tension between the patent holder's exclusive rights and the principle of free trade. A landmark decision by the Japanese Supreme Court on July 1, 1997, famously known as the "BBS case," addressed this issue head-on, clarifying the conditions under which a Japanese patent can be enforced against such parallel imports and discussing the fundamental intellectual property principles of "territoriality" and "independence of patents."

The Factual Background: Patented Wheels Sold in Germany, Imported to Japan

The dispute involved the following parties and circumstances:

- X (Plaintiff/Appellant): A company holding patent rights for an automobile wheel invention in both Japan (the "Japanese Patent") and the Federal Republic of Germany (the "German Counterpart Patent").

- After its German Counterpart Patent came into effect, X manufactured and sold aluminum alloy wheels ("the Products") in Germany, which embodied this German patent.

- Y1 (Defendant/Appellee): Imported these legitimately purchased Products from Germany into Japan.

- Y2 (Defendant/Appellee): Sold these imported Products within Japan.

- X sued Y1 and Y2 in Japan, alleging that the importation and sale of the Products infringed its Japanese Patent. X sought an injunction to stop these activities and claimed damages.

The Tokyo District Court initially ruled in favor of X, finding patent infringement. However, the Tokyo High Court reversed this decision. The High Court reasoned that X's Japanese Patent rights concerning these specific Products had been "exhausted" (消尽した - shōjin shita). It argued that X had already had an opportunity to receive the economic benefit for its invention when the Products were first sold in Germany, and therefore could not assert its Japanese patent rights to prevent their subsequent importation and sale in Japan. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Core Legal Question: Can a Japanese Patent Block Imports of Genuine Goods Sold Abroad by the Patentee?

The Supreme Court was faced with the critical question of whether a patentee who has sold their patented products abroad can then use their corresponding Japanese patent to prevent those same products from being imported into and sold in Japan by third parties.

The Supreme Court's Interpretation of Key Principles

The Supreme Court ultimately dismissed X's appeal, thereby allowing the parallel importation of the specific Products in question. However, it did so based on a different legal theory than the "international exhaustion" doctrine applied by the High Court. The Supreme Court's reasoning involved a careful interpretation of fundamental patent law principles:

1. Paris Convention Article 4bis (Independence of Patents):

The Court first addressed Article 4bis of the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property. This article establishes that patents granted in different member countries for the same invention are independent of each other regarding their grant, validity, duration, and grounds for nullity or forfeiture. The Supreme Court interpreted this to mean that the existence and legal status of a patent in one country are not affected by the fate of a corresponding patent in another country. However, the Court clarified that Article 4bis does not dictate whether a patentee is permitted to exercise their patent rights under specific circumstances, such as in the case of parallel imports.

2. The Principle of Territoriality (属地主義 - zokuchi-shugi):

The Court defined the principle of territoriality in the context of patent rights as meaning that the establishment, transfer, validity, scope of effect, etc., of a patent are determined by the laws of the country for which the patent was granted. Consequently, the effects of a patent are recognized only within the territorial boundaries of that specific country.

3. Crucial Distinction: Exercise of Rights vs. Existence of Rights:

Significantly, the Supreme Court stated that the question of whether a Japanese patent holder can enforce their rights within Japan against products that they (or an equivalent entity) lawfully sold abroad is solely a matter of interpretation of Japanese patent law. The Court explicitly found this issue to be unrelated to, and not in conflict with, either the Paris Convention's principle of patent independence or the principle of territoriality.

The Supreme Court's "Implied License" Doctrine for Parallel Imports

Having established that the issue was one of domestic Japanese patent law interpretation, the Supreme Court laid out its framework, often referred to as the "implied license" or "consent" theory:

The Court acknowledged the highly advanced and widespread nature of international economic transactions in modern society, emphasizing that the freedom of circulation of goods, including through importation, should be respected to the maximum extent possible. It noted that generally, when a product is sold, the seller is understood to transfer all rights they possess in that product to the buyer. Given this context, when a patentee sells a patented product abroad, it is reasonably foreseeable that the purchaser, or subsequent transferees, may seek to import that product into Japan for commercial use or resale.

Based on these considerations, the Supreme Court held the following:

When a Japanese patent holder (or an entity that can be regarded as the same as the patent holder) sells patented products outside of Japan:

- The patent holder cannot exercise their Japanese patent rights against the first purchaser of those products unless there was an explicit agreement between the patent holder and that first purchaser to exclude Japan from the permitted sales territory or region of use for those products.

- The patent holder cannot exercise their Japanese patent rights against subsequent purchasers (those who acquired the products from the first purchaser or further down the distribution chain) unless such an agreement to exclude Japan was made with the first purchaser AND this restriction was clearly and legibly indicated on the products themselves. This ensures that subsequent purchasers are aware of the restriction when they acquire the goods.

The underlying rationale for this rule is that if a patent holder sells a patented product abroad without any such reservations, they are deemed to have implicitly granted the purchaser, and all subsequent transferees, a right to control and dispose of that specific product freely, including importing it into Japan and using or reselling it there, without being subject to the Japanese patent.

Application to the BBS Case

Applying this framework to the facts:

- The aluminum alloy wheels (the Products) were sold in Germany by X itself, the holder of the Japanese Patent.

- X did not present any evidence of an agreement with the German purchasers to exclude Japan as a sales or use territory for these wheels.

- Furthermore, there was no assertion or proof that any such restriction was clearly marked on the Products themselves.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that X was not permitted to exercise its Japanese Patent rights to demand an injunction or seek damages against Y1 and Y2 for importing and selling these specific wheels in Japan.

While the High Court had reached the same outcome (dismissing X's claim), it had relied on the doctrine of "international exhaustion." The Supreme Court affirmed the dismissal but based its decision on this "implied license" or "consent" theory, subject to the patentee's ability to impose explicit restrictions.

Significance and Commentary Insights

This ruling was the first time Japan's Supreme Court had directly addressed the issue of parallel imports of patented goods, and its adoption of the "implied license" framework has been highly influential.

Academic commentary, such as that by Professor Komada, notes several points:

- The Territoriality Principle's Role: While the Supreme Court clearly defined the principle of territoriality, it ultimately deemed it not directly relevant to resolving the parallel import question itself. The question was framed as one of domestic patent law interpretation regarding the exercise of rights, not the existence or scope of the patent grant as defined by territoriality.

- Foundations of Territoriality: There is ongoing academic discussion about the fundamental basis of the territoriality principle in intellectual property law—whether it is an inherent characteristic of sovereign power, a substantive legal principle derived from international treaties like the Paris Convention (via the independence of patents principle), or a conflict of laws rule directing the application of national laws within their respective borders. Professor Komada suggests that limiting a patent's effect territorially to avoid clashing with another country's patent rights might implicitly rely on a prior conflict of laws determination that each country's law governs within its own territory. He views the territorial limitation of rights as fundamentally a conflict of laws principle, and questions whether Article 4bis of the Paris Convention directly mandates such strict territorial limitation of effect, arguing it at most implicitly presupposes it.

Conclusion

The "BBS case" is a landmark decision in Japanese intellectual property law. It established that patented goods legitimately sold abroad by the patentee (or an equivalent entity) can generally be parallel imported into Japan and sold by third parties without infringing the corresponding Japanese patent, under the theory of an "implied license." However, the Supreme Court also provided a clear mechanism for patent holders to retain control over the importation of their products into Japan: they can do so by making explicit contractual agreements with the first purchaser to exclude Japan and by clearly marking the products themselves with this restriction to bind subsequent purchasers. This ruling attempts to strike a balance between protecting the rights of patent holders and promoting the free flow of goods in an increasingly internationalized market.