Pachinko Parlors and Public Morals: Who Has the Right to Challenge Business Permits in Residential Zones?

Judgment Date: December 17, 1998, Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

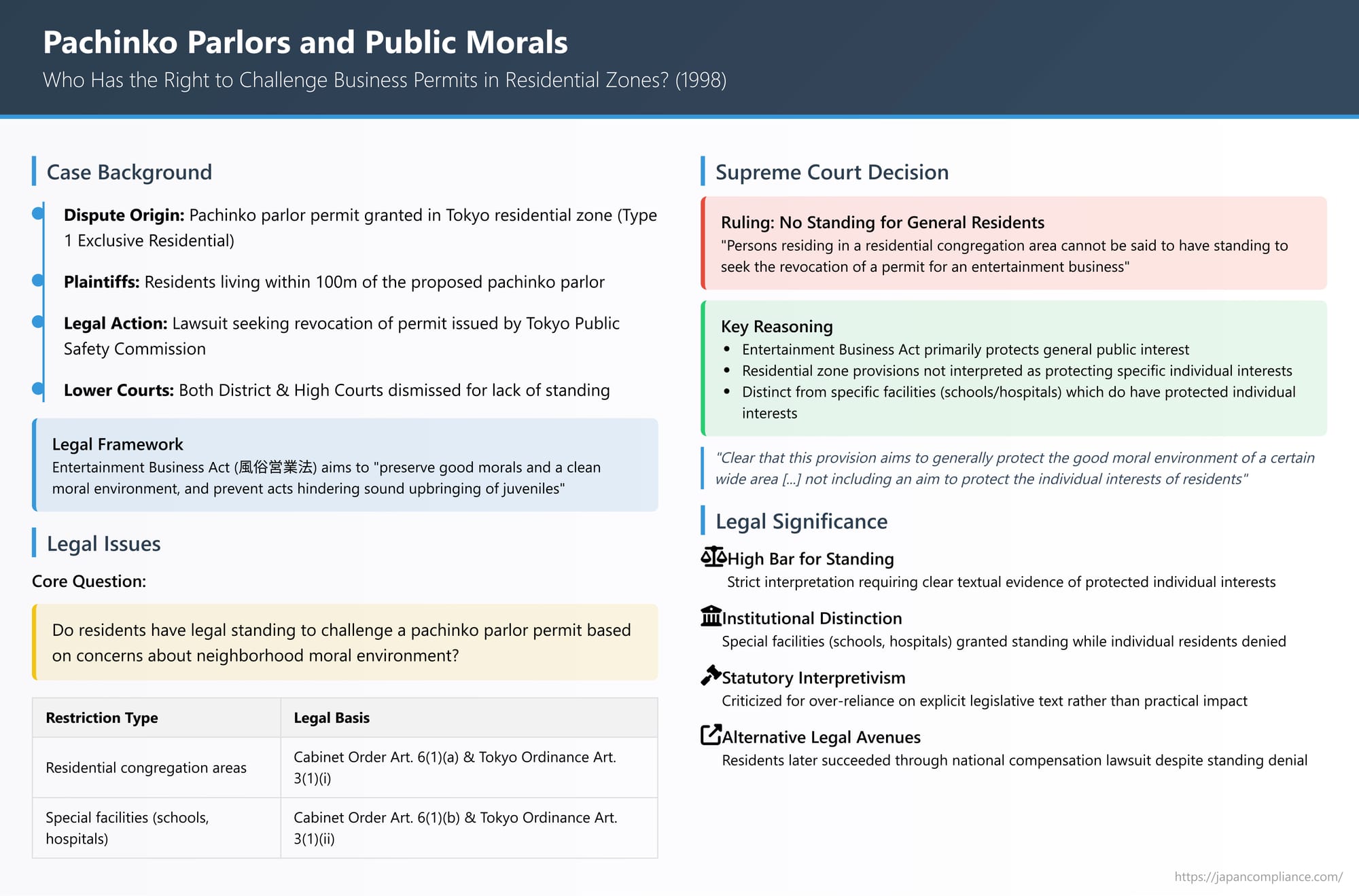

Pachinko parlors are a ubiquitous feature of Japanese urban landscapes, offering a popular form of entertainment. However, their establishment, particularly in or near residential areas, can sometimes lead to concerns from local residents about the potential impact on the neighborhood's "good moral environment" and the well-being of young people. The Act on Control and Improvement of Amusement and Entertainment Business (風俗営業等の規制及び業務の適正化等に関する法律 - Fūzoku Eigyō tō no Kisei oyobi Gyōmu no Tekiseika tō ni kansuru Hōritsu, commonly known as Fūeihō or the Entertainment Business Act) regulates such businesses, including a permit system. A 1998 Supreme Court decision addressed a critical question: do nearby residents have the legal standing to sue for the cancellation of a permit granted to a pachinko parlor if they believe it will negatively affect their community's moral environment?

Regulating "Morals Businesses": The Fūeihō Framework

The Entertainment Business Act (the Act) aims to maintain "good morals and a clean moral environment, and to prevent acts that hinder the sound upbringing of juveniles". To achieve these objectives, the Act establishes a permit system for various types of entertainment businesses, including pachinko parlors. These permits are typically issued by the relevant Prefectural Public Safety Commission.

Article 4, Paragraph 2 of the Act lays out grounds upon which a permit may be denied. One such ground, specified in Item 2, is when the proposed business establishment is located "in an area designated by prefectural ordinance, in accordance with standards set by cabinet order, as one where its establishment needs to be particularly restricted to preserve a good moral environment."

The Cabinet Order (Shikōrei) implementing the Act further specifies standards for these restricted areas. Article 6 of this Order includes, among others:

- Areas where residences are concentrated and land for non-residential use is scarce (termed "residential congregation areas" - 住居集合地域 - jūkyo shūgō chiiki).

- Areas surrounding specific facilities that particularly require the preservation of a good moral environment, such as schools, libraries, child welfare facilities, hospitals, and clinics (referred to as "specific facilities" - 特定施設 - tokutei shisetsu). For these, the restricted zone is generally defined as being within approximately 100 meters of such facilities.

Based on these national laws, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government had enacted its own ordinance (Jōrei). Article 3 of this Tokyo ordinance designated restricted areas, including, as a general rule, Type 1 Exclusive Low-Rise Residential Zones (a type of "residential congregation area") and areas within 100 meters of specified facilities like schools and hospitals.

The Tokyo Pachinko Parlor Dispute: Facts of the Case

The case involved a permit granted by Y (the Tokyo Metropolitan Public Safety Commission) under Article 3, Paragraph 1 of the Act for the operation of a pachinko parlor. X et al., a group of residents living within 100 meters of the building housing the proposed pachinko parlor, filed a lawsuit seeking the revocation of this permit. They argued that the pachinko parlor was located within a Type 1 Exclusive Residential Zone, which they contended was a "residential congregation area" where such businesses should be restricted, making the permit illegal.

A key preliminary issue in the lawsuit was whether X et al., as nearby residents, had the necessary legal standing (plaintiff standing, or 原告適格 - genkoku tekkaku) to bring such a challenge.

The Tokyo District Court (First Instance) dismissed the lawsuit, finding that X et al. lacked the requisite standing.

The Tokyo High Court (Second Instance) upheld the District Court's decision, also dismissing the appeal for lack of standing. X et al. then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (December 17, 1998): No Standing for General Residents in This Context

The Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, dismissed the appeal by X et al., thereby affirming the lower courts' conclusion that these residents lacked standing to challenge the pachinko parlor permit on the grounds asserted.

The Court's reasoning centered on the interpretation of "legal interest" as required for plaintiff standing under Article 9 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA, old version then in force):

I. Reaffirming the "Legally Protected Interest" Standard

The Court began by reiterating its established doctrine on standing: a "person who has 'legal interest' ... to seek the revocation of the said disposition" is one "whose rights or legally protected interests are infringed, or are inevitably threatened with infringement, by the said disposition". Furthermore, if the administrative statute that provides the basis for the disposition "is construed as including an aim to protect, as individual interests of each person to whom they belong, the concrete interests of an unspecified number of persons, beyond merely absorbing and dissolving them into the general public interest, then such interests also qualify as 'legally protected interests' herein". The determination of whether a statute includes such an aim is to be made by considering "the purpose and objective of the said administrative statute, and the content and nature of the interests that the said administrative statute seeks to protect through the said disposition".

II. Purpose of the Fūeihō (Entertainment Business Act) – Primarily General Public Interest

Applying this framework, the Supreme Court first looked at Article 1 of the Entertainment Business Act, which states that the Act aims to "preserve good morals and a clean moral environment, and to prevent acts that hinder the sound upbringing of juveniles". The Court found that from this purpose clause, it was "difficult to read" an intent for the Act's permit-related provisions to protect specific individual interests in addition to these general public interests.

III. Permit Criteria (Act Art. 4(2)(ii)) and the Role of Lower-Level Regulations

The Court then examined Article 4, Paragraph 2, Item 2 of the Act, which allows for the denial of a permit if an establishment is in a restricted area defined by prefectural ordinance based on cabinet order standards for preserving a good moral environment. The Court interpreted this provision as "envisaging the designation of restricted areas for entertainment businesses from a public interest standpoint of preserving a good moral environment". It noted that while this statutory provision did not necessarily forbid the implementing cabinet order or prefectural ordinances from also protecting individual interests, the Act itself (Art. 4(2)(ii)) was "difficult to construe as aiming to protect the individual interests of residents in such restricted areas".

IV. Distinguishing Between Types of Restricted Areas (Cabinet Order and Tokyo Ordinance)

This led to a crucial distinction based on the implementing Cabinet Order and the Tokyo Metropolitan Ordinance:

- Protection for Specific Facilities: The Court acknowledged that the Cabinet Order (Article 6(1)(b) and 6(2)), which provides for restricting entertainment businesses within approximately 100 meters of specific facilities like schools and hospitals, is "construed as intending to particularly protect the individual interests of the installers of said specific facilities". Consequently, the Tokyo Ordinance (Article 3(1)(ii)), which implements this standard, was understood to protect the interest of such facilities "to operate smoothly in a good and quiet environment". This was consistent with a prior Supreme Court ruling (from 1994) that had affirmed standing for a clinic located near a proposed entertainment business.

- No Specific Individual Protection in "Residential Congregation Areas": In contrast, the Cabinet Order's provision (Article 6(1)(a)) allowing restrictions in "residential congregation areas" was seen differently. The Court found it "clear that this provision aims to generally protect the good moral environment of a certain wide area, and there is no wording, unlike in item (b) [for specific facilities], that suggests the protection of specific individual interests". Coupled with the general public interest focus of the Act's main purpose clause and permit criteria, the Court concluded that the Cabinet Order's provision for "residential congregation areas" was "solely from the viewpoint of public interest protection".

- Tokyo Ordinance Following Suit: Therefore, the Tokyo Ordinance provision (Article 3(1)(i)) establishing restrictions in "residential congregation areas" (like the Type 1 Exclusive Residential Zone in question) was "construed as not including an aim to protect the individual interests of residents" in such areas.

V. Conclusion: No Standing for General Residents in This Specific Context

Based on this interpretation, the Supreme Court concluded that "persons residing in a residential congregation area cannot be said to have standing to seek the revocation of a permit for an entertainment business". Since X et al.'s claim was based on their residence in such an area and their general interest in its moral environment, they lacked the specific, individually protected legal interest required for standing.

The "Legally Protected Interest" Test: A High Bar for Residents?

This 1998 decision illustrates the Supreme Court's application of the "legally protected interest" test for plaintiff standing. It underscores the judiciary's tendency to look for clear textual evidence within the empowering statute (or its closely related implementing regulations) indicating an intent to protect the specific individual interests of the plaintiffs, as opposed to interests they hold merely as members of the general public.

Critiques of the Reasoning

The Court's reasoning in this case has drawn considerable academic commentary and critique:

- Statute-Based Interpretivism: One line of criticism, as noted in the PDF commentary, questions the heavy reliance on "statute-based interpretivism" (制定法準拠主義 - seiteihō junkyo shugi). The argument is that legislators, when drafting laws, do not typically have the specific criteria for plaintiff standing at the forefront of their minds. Therefore, trying to divine an intent to protect individual interests solely from the text of the empowering statute can be problematic.

- Interpreting Laws via Lower-Level Regulations: The PDF commentary also points out that the Supreme Court's approach of using the Cabinet Order (a lower-level regulation) to interpret the scope of protection afforded by the Act (a law passed by the Diet) can be questioned, particularly if it appears to limit the protective scope of the higher law. If the Act allows for broader protection, can a Cabinet Order narrow it for standing purposes?

- Consistency in Protecting Interests: A significant critique highlighted in the commentary is the apparent inconsistency in recognizing individual interests. Why should a specific facility like a clinic or hospital have its "interest in operating smoothly in a good and quiet environment" recognized as individually protected from a nearby pachinko parlor, while residents living even closer and potentially facing more direct impacts on their "interest in living in a good moral environment" are deemed to hold only a general public interest? Some argue that the latter interest is just as, if not more, direct and individual for those immediately affected.

A Postscript: Success Through a Different Legal Avenue

Interestingly, the PDF commentary mentions a subsequent development in this specific dispute. Although X et al. were denied standing to directly revoke the permit, they later pursued a national compensation lawsuit (a civil suit for damages against the state). In that separate action, a different court reportedly found the original pachinko parlor permit to have been illegal. This led to administrative measures by the Tokyo Public Safety Commission that effectively addressed the residents' original concerns. This outcome, where the permit was deemed illegal in a different legal context, raises questions about the practical utility of a very narrow interpretation of standing for direct revocation lawsuits if the challenged administrative act is indeed substantively unlawful.

The Impact of Subsequent ACLA Reforms

It is important to note that the Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA) was revised in 2004, after this 1998 judgment. The revised Article 9, Paragraph 2 now explicitly directs courts to consider various factors when determining "legally protected interest," including the purpose of the empowering statute and any related laws, as well as the content, nature, manner, and extent of the harm that would be suffered if the disposition were illegal. This amendment was generally intended to provide clearer guidance and potentially broaden access to courts.

However, the PDF commentary suggests that even after this revision, the Supreme Court has often continued to emphasize a statute-based approach, typically requiring clear textual "hooks" or indications within the relevant laws that demonstrate an intent to protect specific individual interests. The assessment of whether an interest is "individual" or merely part of the "general public interest" remains a critical, and sometimes challenging, judicial determination.

Conclusion

The 1998 Supreme Court decision regarding the Tokyo pachinko parlor permit is a key case illustrating the application of the "legally protected interest" standard for plaintiff standing in Japan. The Court held that general residents of a "residential congregation area" did not have standing to challenge a permit for an entertainment business based solely on concerns for the area's overall moral environment, as the relevant legal provisions were interpreted as primarily protecting general public interests rather than their specific individual interests in this regard. Standing was, however, recognized for specific facilities like schools or hospitals whose operational environment was deemed to be individually protected by proximity-based restrictions.

The decision highlights the judiciary's meticulous, statute-focused approach to determining standing, requiring plaintiffs to demonstrate that the law under which an administrative action is taken intends to protect their claimed interest as a distinct, individual one. While later legislative reforms and evolving case law continue to shape the contours of plaintiff standing, this case remains an important example of the high bar that can exist for citizens seeking to directly challenge administrative permits based on broader community or environmental concerns, unless a specific, individually protected legal interest can be clearly identified within the governing statutes.