Ownership in Dispute: A Landmark Japanese Ruling on Destroying Property Amidst a Legal Battle

In the high-stakes world of business and finance, disputes over property ownership are not uncommon. A loan defaults, collateral is seized, and suddenly the question of who truly owns an asset becomes a contentious legal battle. But what happens if one party, convinced of their own rightful ownership, takes matters into their own hands? If you believe the foreclosure on your house was fraudulent, is it a crime to damage that house while the legal title is held by the bank? Does the criminal law have to wait for the civil courts to render a final verdict on ownership before it can intervene?

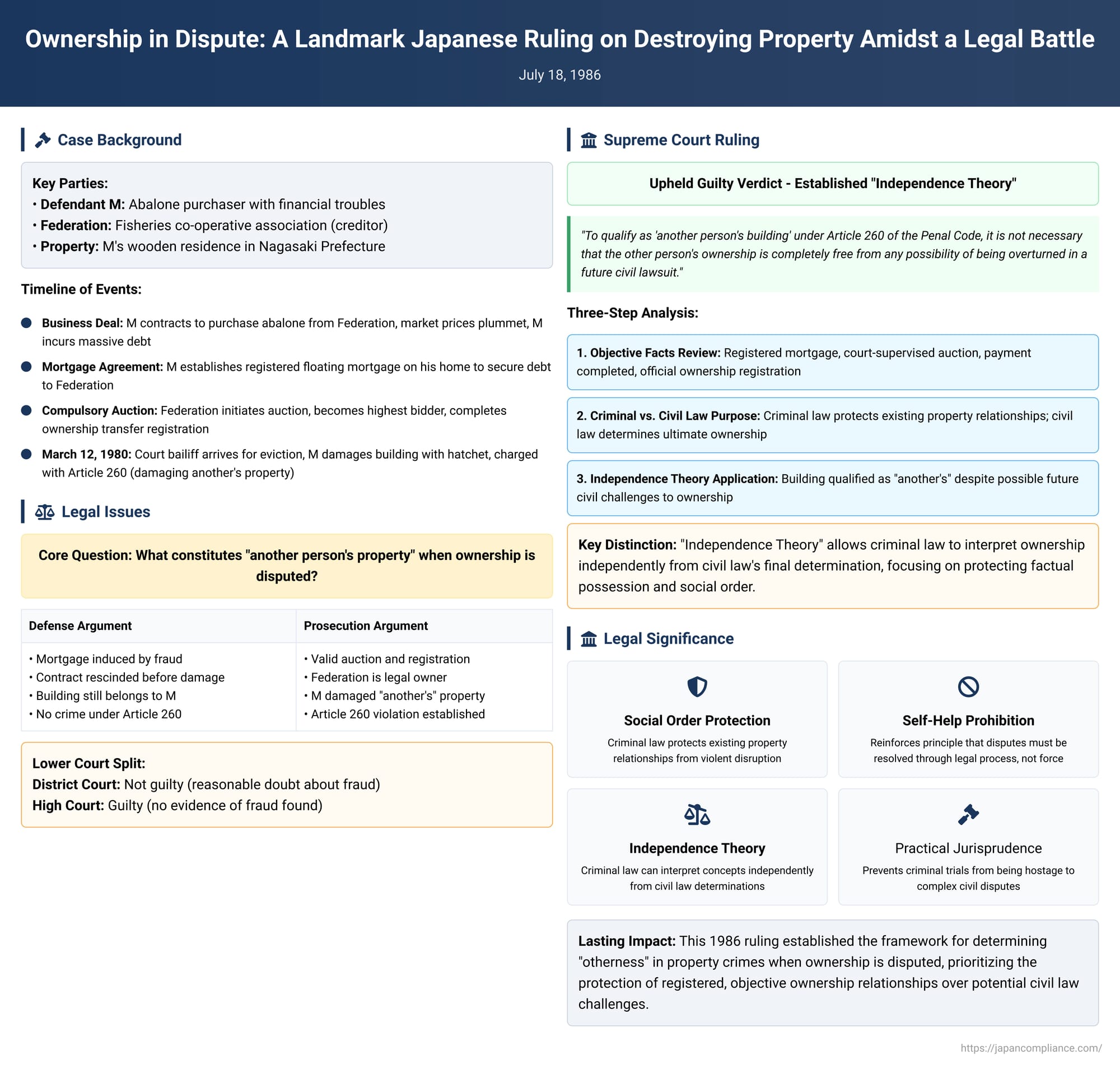

This complex intersection of civil property rights and criminal liability was the focus of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on July 18, 1986. The case forced the Court to decide a fundamental question: to prosecute someone for damaging "another person's property," must the prosecution prove that person's ownership beyond any possible doubt, even when the ownership itself is the subject of an ongoing civil dispute? The Court's answer established a pivotal legal doctrine, drawing a nuanced line between the ultimate determination of property rights and the immediate protection of social order.

The Facts: A Business Deal Gone Sour

The case began with a series of sour business dealings in Nagasaki Prefecture. The defendant, M, had entered into a contract with a prefectural federation of fisheries co-operative associations (hereafter, "the Federation") to purchase a large quantity of abalone. However, when the market price for abalone plummeted, M faced catastrophic losses and found himself deeply in debt to the Federation.

To secure this debt, M agreed to establish a neteitōken (a type of floating or revolving mortgage common in Japan) on his own wooden residence in favor of the Federation. This mortgage was officially registered, creating a legal encumbrance on the property. When M was unable to satisfy the debt, the Federation initiated a compulsory auction for the building based on its mortgage rights. In the auction proceedings, the Federation itself emerged as the highest bidder, paid the purchase price to the court, and completed the registration of ownership transfer, making it the new legal owner of the building on paper.

The situation came to a head on March 12, 1980. A court bailiff arrived at the residence to execute a formal eviction order. Enraged by what he perceived as an injustice, M grabbed a hatchet and began to violently damage the building, striking pillars and other structural components. Even after the bailiff left, M continued his destructive acts. He was subsequently indicted for the crime of damaging another person's building, under Article 260 of the Japanese Penal Code.

The Legal Battlefield: A Question of True Ownership

In court, M's defense was not a denial of the act itself, but a powerful challenge to a core element of the crime: the "otherness" of the property. He argued that the building was not "another person's," but was, in fact, still his own.

His claim was that his initial agreement to the mortgage was induced by fraud. He alleged that Federation officials had misled him, suggesting the mortgage was a mere formality and would never actually be enforced. Believing this, he signed the agreement. M claimed that he had declared his intent to rescind this fraudulent contract before he damaged the building. Under Japanese civil law, a contract induced by fraud can be rescinded, rendering it void from the beginning. If the mortgage was void, the subsequent auction and ownership transfer to the Federation were legally baseless. The true owner, he argued, was still M. Therefore, he had only damaged his own property, an act not punishable under Article 260.

This argument created a deep split in the lower courts.

- The District Court (first instance): Found M not guilty. The judges concluded that the possibility of fraud in the mortgage agreement could not be entirely dismissed. Because there was reasonable doubt as to whether the Federation was the legitimate owner, the prosecution had failed to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the building was "another person's."

- The High Court (second instance): Overturned the acquittal and found M guilty. The appellate judges conducted their own review and concluded that there was no fraud. They held that the building was legally owned by the Federation at the time of the incident, making M's actions a crime.

The conflicting verdicts highlighted the central dilemma. Must a criminal court definitively resolve a complex civil law dispute about fraudulent contracts and property titles just to determine guilt or innocence for a property damage charge? The case was appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision

The Supreme Court upheld the guilty verdict, but on significantly different grounds. It introduced a new way of thinking about the element of "otherness" in property crimes. The Court's core holding was concise and transformative:

"To qualify as 'another person's building' under Article 260 of the Penal Code, it is not necessary that the other person's ownership is completely free from any possibility of being overturned in a future civil lawsuit."

The Court reasoned that, given the objective facts of the case—the registered mortgage, the completed court-supervised auction, the payment of the purchase price, and the official registration of the Federation's ownership—the building qualified as "another person's" for the purposes of criminal law. This was true even if one accepted the District Court's view that the possibility of the mortgage being voided for fraud could not be completely ruled out.

Analysis: The "Independence" vs. "Subordination" Theories

This ruling is the leading expression of the "Independence Theory" (dokuritsu-setsu) in Japanese criminal law, a departure from the more traditional "Subordination Theory" (jūzoku-setsu).

The Subordination Theory

This older view, which implicitly guided the lower courts, holds that the definition of legal concepts in the Penal Code (like "another's property") should be strictly subordinate to their definitions in the Civil Code. If, under a proper application of civil law, M was still the true owner, then the building simply was not "another's," and no crime under Article 260 could have been committed. This approach prioritizes the unity of the legal system, ensuring a concept like "ownership" means the same thing across all legal fields.

The Independence Theory

The Supreme Court, however, charted a new course. The Independence Theory posits that the Penal Code can, to a certain extent, interpret these concepts independently of their final determination in civil law. The rationale for this view was powerfully articulated in a supplementary opinion by one of the justices.

The opinion drew a distinction between the purposes of civil and criminal law:

- Civil Law's Purpose: To definitively and ultimately determine who owns what, thereby providing finality and stability to property relations.

- Criminal Law's Purpose: To protect the existing, de facto state of property relations from being destroyed by force, thereby preventing the disruption of social order.

From the criminal law's perspective, what matters is the "actual ownership relationship" as it appears in society. When there is an objective situation in which an asset is, by all outward appearances, believed to belong to a specific person (in this case, the Federation, backed by a court auction and official title registration), and there is no obvious and clear reason to deny that ownership, the criminal law must protect that relationship from violent self-help. The criminal court's job is not to be the final arbiter of a tangled civil dispute, but to protect the established, peaceful order.

This view is underpinned by the fundamental principle of the prohibition of self-help (jiryoku kyūsai no kinshi). Even if you firmly believe you are in the right, you are not permitted to use force to vindicate your claim. You must rely on the legal process. M's act of taking a hatchet to the building was a classic example of resorting to self-help instead of pursuing his claims through civil litigation.

Deeper Implications and Modern Relevance

The 1986 decision reflects a broader shift in the understanding of what property crime laws protect. The focus moves away from an abstract, ultimate "right of ownership" (honken) and toward the protection of more tangible, real-world interests:

- Protected Economic Interests: The Federation, having paid for the building at auction and registered its title, had a clear and substantial economic interest that society would deem worthy of respect and protection, regardless of any lingering disputes about the original mortgage.

- Factual Peace and Order: The ruling protects the stable state of affairs represented by the property register. It reinforces the idea that the official public record of ownership should be trusted and defended against violent disruption until it is formally changed through proper legal channels.

While the Independence Theory has been criticized by some scholars for potentially creating inconsistencies between civil and criminal law, its practical wisdom is compelling. It frees criminal courts from the immense burden of resolving every civil law nuance in a case, allowing them to focus on their core mission: preventing violence and maintaining public order. It also avoids a situation where the outcome of a criminal trial could be held hostage for years, pending the resolution of a parallel civil case.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1986 decision is a masterful navigation of a complex legal boundary. It affirms that in a civilized society, disputes over rights must be resolved through legal process, not through force. For the purpose of criminal liability, property belongs to "another" when there are strong, objective, and public indicators of their ownership, such as a registered title obtained through a court-sanctioned process. The mere possibility that this title could be challenged or even overturned in a future civil suit is not a license for its destruction. By punishing the defendant's act of violent self-help, the Court powerfully reinforced the principle that the stability of the existing social and economic order is a paramount legal value, worthy of the criminal law's protection.

Citations

- The defendant M entered into a contract to purchase abalone from a prefectural federation of fisheries co-operative associations ("the Federation") but subsequently incurred a large debt when market prices fell.

- To secure the debt, M established a registered floating mortgage on his home in favor of the Federation.

- The Federation initiated an auction based on the mortgage, became the successful bidder, paid the price, and completed the ownership transfer registration.

- When a court bailiff came to execute an eviction order, M became enraged and damaged the building's pillars with a hatchet.

- M claimed the mortgage was based on fraud, as he was allegedly told it was a mere formality, and that he had rescinded the agreement before the damage occurred, meaning he was still the rightful owner.

- The district court found M not guilty, reasoning that the possibility of fraud could not be ruled out, thus creating reasonable doubt as to whether the building belonged to "another".

- The high court reversed this, finding no evidence of fraud and convicting M.

- The Supreme Court's majority opinion held that to be considered "another's building," it is not required that the other's ownership is free from any possibility of being denied in a future civil lawsuit.

- Given the objective facts like the auction and registration, the building was deemed "another's" for criminal law purposes, even if the possibility of fraud in the initial contract remained.

- A supplementary opinion distinguished the goals of civil law (determining ultimate ownership) from criminal law (protecting the actual, existing ownership relationship from destruction).

- This opinion argued that when an objective situation exists where an asset is widely believed to belong to a specific person, and there is no clear reason to deny that ownership, the criminal law must protect that relationship from violent self-help.

- The core debate in this area of law is between the "Subordination Theory," where criminal law's definitions follow civil law, and the "Independence Theory," where criminal law can make its own determination. This decision is a key example of the Independence Theory.

- The Independence Theory is supported by the idea that even if a mortgage were subject to rescission due to fraud, the mortgagee still possesses an "economic interest worthy of respect in social contemplation," especially after a public auction and registration.

- This approach is also rooted in the principle of prohibiting self-help and protecting the factual state of social and economic order.

- One policy consideration behind the Independence Theory is to avoid the practical difficulty of criminal courts having to definitively resolve complex civil law disputes, and to prevent contradictions between civil and criminal rulings.

- While scholarly opinion in Japan has been leaning toward the Subordination Theory, the practical influence of the Independence Theory as established in this case remains significant, and the two theories are not always mutually exclusive. Both theories would likely agree that in a case of disputed ownership, parties are expected to refrain from using force and maintain the status quo while seeking resolution through proper legal channels.