Overwork, Pre-Existing Conditions, and Workers' Comp: Japan's Supreme Court Links Chauffeur's Stroke to Job Burden (July 17, 2000)

Japan’s Supreme Court held that 18 months of extreme overtime outweighed mild hypertension, ruling a chauffeur’s 2000 stroke compensable and redefining overwork disease criteria.

TL;DR

A 2000 Supreme Court ruling found that a chauffeur’s subarachnoid hemorrhage was work‑related, even with mild pre‑existing hypertension, because 18 months of extreme overtime, irregular hours, and chronic fatigue aggravated his condition beyond its natural course. The decision paved the way for broader recognition of karōshi‑related cerebrovascular illnesses under Japan’s workers’‑comp scheme.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: The Life of a Dedicated Chauffeur

- Medical Background and the Hemorrhage

- Legal Proceedings: Work‑Relatedness Denied

- Legal Framework: “Work‑Related Illness”

- The Supreme Court’s Analysis (July 17 2000): Overwork as a Decisive Factor

- Implications and Significance: Recognizing the Impact of Overwork

- Conclusion

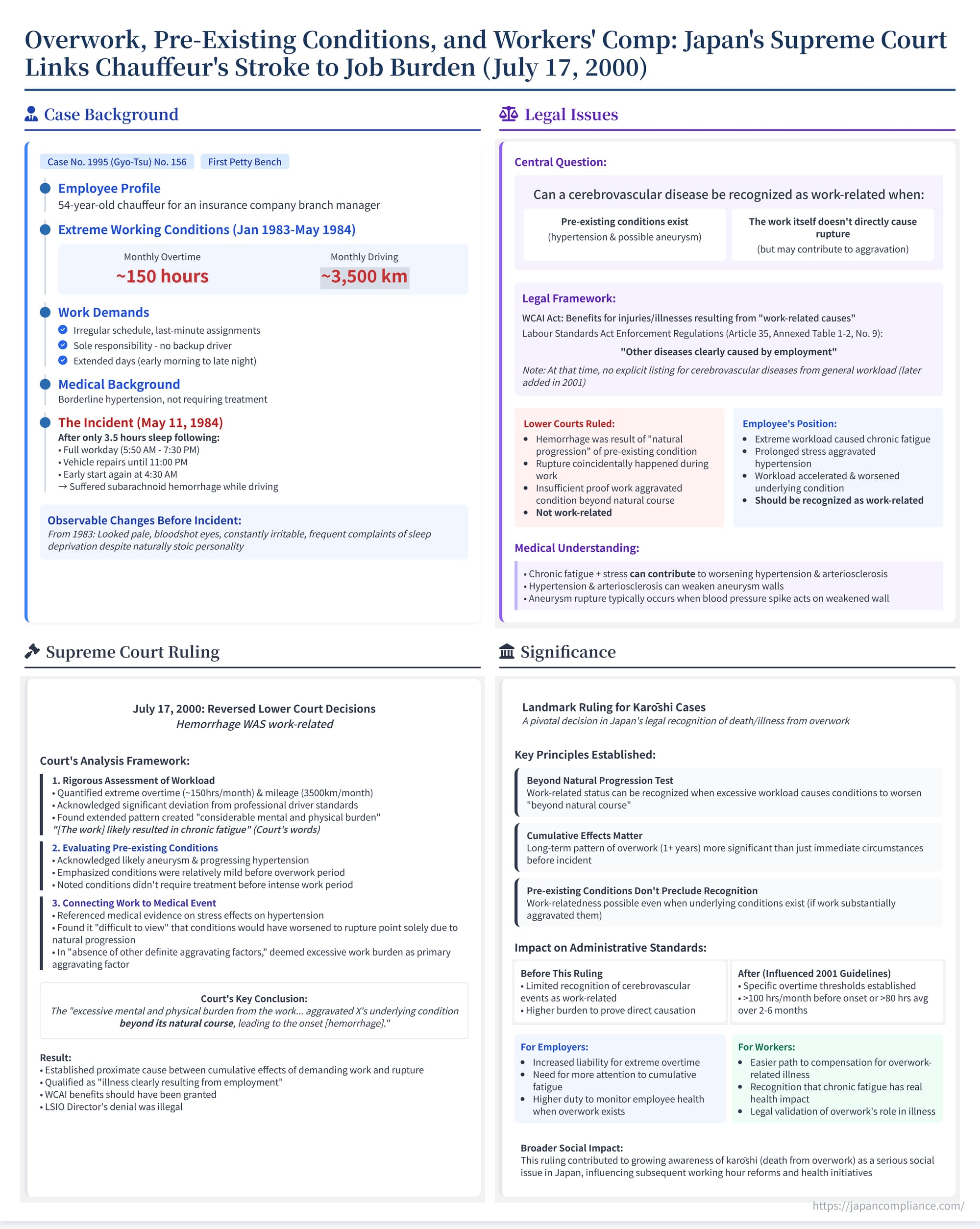

On July 17, 2000, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark judgment concerning the criteria for recognizing cerebrovascular diseases, such as stroke, as work-related illnesses eligible for benefits under the Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act (WCAI Act, or Rōsai Hoken Hō - 労災保険法) (Case No. 1995 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 156, "Temporary Absence Compensation Non-Payment Decision Revocation Case"). The case involved a company chauffeur who suffered a subarachnoid hemorrhage while on duty. Despite the employee having pre-existing conditions that could contribute to such an event, the Court overturned lower court decisions and found the illness to be work-related. It based its conclusion on a detailed assessment of the employee's extremely demanding workload over a prolonged period, finding that the accumulated fatigue and stress constituted an excessive burden that aggravated his underlying conditions beyond their natural course, thereby establishing legal causation between the work and the hemorrhage. This decision significantly influenced the legal and administrative approach to recognizing illnesses linked to overwork (karō) in Japan.

Factual Background: The Life of a Dedicated Chauffeur

The case painted a stark picture of the working life of the appellant, X, leading up to his illness:

- The Job: X (54 years old at the time of the incident) was employed by a driver dispatch company but assigned exclusively as the chauffeur for the branch manager of the Yokohama Branch of Company B. His duties went beyond simply driving; he was responsible for transporting the manager for daily commutes, tours of branch offices across Kanagawa Prefecture, client visits, and entertainment functions (including trips to restaurants and golf courses in areas like Izu Hakone). He also drove other executives and clients.

- Sole Responsibility: As the only dispatched driver for the Yokohama branch, X was solely responsible for the vehicle's maintenance, including daily cleaning, washing and waxing every few days, and performing minor repairs himself, as no backup vehicle was provided.

- Irregular and Demanding Schedule: Driving schedules were often communicated at the last minute, requiring X to remain constantly alert and ready during waiting periods. While official working hours were set (e.g., 8:30 AM - 5:30 PM weekdays), the reality, especially after a change in branch managers in July 1981, involved significantly longer hours. Commutes to the new manager's residence in Shinjuku, Tokyo (required about half the month) extended driving distances and stretched workdays from early morning often late into the night.

- Extreme Overwork Statistics (Jan 1983 - May 1984):

- Overtime: Averaged approximately 150 hours per month.

- Mileage: Averaged approximately 3,500 kilometers per month.

- Post-December 1983: The workload intensified further. Average daily overtime exceeded 7 hours, frequently including late-night hours. Monthly mileage remained very high.

- Comparison to Standards: The Court noted that X's working conditions significantly exceeded the standards established by the Ministry of Labour for professional drivers (specifically citing the criteria for taxi drivers). X's monthly duty hours were often near or above the maximum limit (325 hours), daily duty hours frequently surpassed the maximum (13 hours), and rest periods between workdays were often less than the required minimum (8 continuous hours).

- Events Leading Up to the Hemorrhage:

- April 1984: Was a particularly strenuous month. Average daily overtime still exceeded 7 hours, and the average daily mileage (~192 km) was the highest recorded since December 1983. This included a demanding overnight trip (April 13-14) involving long drives to Hakone, where X reportedly got no sleep due to a roommate's snoring, leaving him unwell afterward.

- Early May 1984: Despite some intermittent holidays in late April/early May, the pattern of long hours continued. Between May 1 and May 10, there were two days when work finished after midnight and two days with driving distances over 260 km.

- May 10-11 (Final 24 Hours): On May 10, X started work at 5:50 AM. He returned to the garage around 7:30 PM but discovered an oil leak. X performed the repairs himself, finishing around 11:00 PM. He went to bed around 1:00 AM on May 11. On May 11, after only approximately 3.5 hours of sleep, X woke up around 4:30 AM, went to the garage before 5:00 AM for the pre-operation check, and left in the car to pick up the branch manager. Shortly after starting the drive, he felt unwell and suffered the subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Medical Background and the Hemorrhage

- X's Pre-existing Conditions: Health checkups in October 1981 and October 1982 showed X's blood pressure was in the borderline range between normal and hypertensive. While indicating progressing hypertension, it was not considered severe enough to require medical treatment at that time. X had no detrimental lifestyle habits like smoking or heavy drinking.

- Observed Changes: However, from around 1983 onwards, X often looked pale, had bloodshot eyes, seemed constantly irritable, and frequently complained of lack of sleep, despite having a naturally stoic personality.

- Medical Explanation of Hemorrhage: X's subarachnoid hemorrhage was highly likely caused by a ruptured cerebral aneurysm. While the origin of X's specific aneurysm (congenital vs. acquired) was unknown, and the direct causal link between hypertension and aneurysm formation is not fully established, medical understanding indicated that:

- Chronic hypertension and arteriosclerosis are known to worsen existing aneurysms, weakening their walls.

- Chronic hypertension is a major risk factor for subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- Aneurysm rupture typically occurs when a transient spike in blood pressure acts upon a critically weakened and enlarged aneurysm wall. Such spikes are often associated with sudden physical exertion or straining (even routine daily activities) rather than just sustained high blood pressure or mental stress alone.

- Importantly, chronic fatigue and sustained excessive stress can be contributing factors to the development or worsening of chronic hypertension and arteriosclerosis. However, fatigue and stress themselves are not considered direct causes of the hemorrhage event (the rupture).

Legal Proceedings: Work-Relatedness Denied

X filed a claim for WCAI benefits (specifically, Temporary Disability Compensation Benefits - Kyūgyō Hoshō Kyūfu). The appellee, Y (the Director of the Yokohama South Labour Standards Inspection Office), denied the claim, determining that the subarachnoid hemorrhage was not a "work-related illness" (gyōmu-jō no shippei). X sued to revoke this non-payment decision.

The High Court eventually ruled against X, agreeing with the LSIO Director. The High Court essentially concluded that X's hemorrhage was the result of the "natural progression" (shizen zōaku) of a pre-existing condition (the likely aneurysm) and that it merely happened to rupture coincidentally while X was performing his driving duties. It found insufficient proof that the work itself caused the aneurysm or significantly aggravated the underlying hypertension beyond its natural course to trigger the rupture. Therefore, it did not qualify as an "illness clearly resulting from employment" under the relevant Labour Standards Act Enforcement Regulations.

Legal Framework: "Work-Related Illness"

The WCAI Act provides benefits for injuries, illnesses, disabilities, or death resulting from "work-related causes" (gyōmu-jō no jiyū). For illnesses, this generally requires establishing a causal link between the employment conditions and the onset or aggravation of the illness.

The Labour Standards Act Enforcement Regulations (Article 35, Annexed Table 1-2) list specific occupational diseases presumed to be work-related. At the time of this case, cerebrovascular diseases like stroke or subarachnoid hemorrhage resulting from general workload were not explicitly listed (though they were added later in 2001). Therefore, X's case fell under the catch-all category (then No. 9): "other diseases clearly caused by employment" (その他業務に起因することの明らかな疾病 - sonota gyōmu ni kiin suru koto no akiraka na shippei). This required proving a strong causal connection between X's work and his hemorrhage. The presence of pre-existing conditions like hypertension and a potential aneurysm complicated this determination, raising the question of whether the illness was primarily due to work or simply the natural progression of these underlying issues.

The Supreme Court's Analysis (July 17, 2000): Overwork as a Decisive Factor

The Supreme Court disagreed strongly with the High Court's assessment and overturned its decision, finding that X's subarachnoid hemorrhage was work-related. The Court conducted a detailed analysis focusing on the interaction between X's extreme workload and his underlying health conditions.

1. Rigorous Assessment of Workload ("Overwork" - Karō):

The Court meticulously recounted the facts demonstrating the severity and chronicity of X's workload:

- Nature of Work: Inherently stressful (chauffeur for executive), irregular schedule, long hours (early morning to late night), high mileage, long waiting times requiring alertness, sole responsibility for vehicle maintenance.

- Quantified Overload: Acknowledged the extremely high average monthly overtime (~150 hours) and mileage (~3500 km) for over a year, with daily overtime routinely exceeding 7 hours in the final months. Noted the significant deviation from established standards for professional drivers.

- Accumulated Fatigue: Explicitly stated that the "continuation of such duties... became a considerable mental and physical burden for X and likely resulted in chronic fatigue." (kinmu no keizoku ga X ni totte seishinteki, shintaiteki ni kanari no fuka to nari manseiteki na hirō o motarashita koto wa hitei shigatai).

- Acute Stressors: Highlighted the particularly demanding period in the month before the incident (record mileage, exhausting overnight trip causing illness) and the final 24 hours involving late-night repairs after a long workday followed by drastically insufficient sleep (approx. 3.5 hours).

2. Evaluating the Role of Pre-existing Conditions:

The Court acknowledged X's likely aneurysm and progressing hypertension but critically emphasized that these conditions were relatively mild (borderline) and did not require treatment before the period of intense overwork began. It also noted the absence of other contributing lifestyle factors.

3. Connecting Workload, Aggravation, and Onset:

The Court then linked the extreme workload to the medical event, rejecting the "natural progression" theory:

- Medical Science Context: Referenced the medical understanding that chronic fatigue and excessive stress can contribute to the worsening of hypertension and arteriosclerosis, which in turn weakens aneurysm walls.

- Improbability of Natural Progression: Given X's previously manageable health status, the Court found it "difficult to view" that his underlying conditions would have worsened solely due to their natural course to the point of imminent rupture by the time of the incident.

- Work as the Primary Aggravating Factor: In the "absence of other definite aggravating factors" (hoka ni kakutaru zōaku yōin o miidasenai honken ni oite wa), the Court concluded it was "reasonable to consider" (miru no ga sōtō) that the "excessive mental and physical burden from the work... aggravated X's underlying condition beyond its natural course, leading to the onset [hemorrhage]."

- Establishing Legal Causation: This finding established the necessary proximate cause relationship (sōtō inga kankei) between the cumulative effects of X's demanding work and the rupture of the aneurysm.

Conclusion on Work-Relatedness: Therefore, X's subarachnoid hemorrhage qualified as an "illness clearly resulting from employment" under the applicable LSA Regulations and was thus compensable under the WCAI Act. The denial of benefits by the LSIO Director was illegal.

Implications and Significance: Recognizing the Impact of Overwork

This 2000 Supreme Court decision was a landmark ruling in the context of karōshi (death from overwork) and related health issues in Japan.

- Legal Recognition of Overwork's Impact: It strongly affirmed that severe and prolonged overwork, leading to chronic fatigue and stress, can be recognized legally as a substantial contributing factor to the onset or significant aggravation of cerebrovascular diseases like subarachnoid hemorrhage or stroke, even when pre-existing conditions are present.

- Beyond Natural Progression: The key analytical step was determining whether the workload likely caused the underlying condition to worsen "beyond its natural course" (sono shizen no keika o koete zōaku sase). If the work burden is deemed sufficiently excessive, it can be seen as interrupting the natural progression and precipitating the adverse health event.

- Emphasis on Cumulative Fatigue: The judgment highlighted the importance of considering the cumulative effect of fatigue and stress over a long period, not just the workload immediately preceding the event. The Court meticulously detailed the work patterns over the preceding 1.5 years.

- Influence on Administrative Standards: This ruling, along with similar cases, significantly influenced the development and revision of administrative guidelines for recognizing work-related cerebrovascular and ischemic heart diseases. While this specific judgment predated the precise overtime hour thresholds introduced in the Heisei 13 (2001) administrative criteria (e.g., >100 hours overtime in the month before onset, or >80 hours average over 2-6 months), it laid the groundwork for recognizing long hours and chronic fatigue as key factors in the causality assessment.

- Shift in Perspective: It marked a notable shift towards acknowledging the serious health consequences of the demanding work culture prevalent in parts of the Japanese economy and strengthening the legal basis for compensating victims of overwork-related illnesses.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's July 17, 2000, decision established that a subarachnoid hemorrhage suffered by a chauffeur could be deemed a work-related illness under Japan's Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act, despite his pre-existing hypertension and likely aneurysm. The Court found that the employee's exceptionally long working hours, irregular schedule, high stress, and resulting chronic fatigue over a prolonged period constituted an excessive burden that aggravated his underlying conditions beyond their natural course, ultimately leading to the hemorrhage. This landmark ruling emphasized the importance of considering cumulative workload and fatigue in assessing the work-relatedness of cerebrovascular events and significantly impacted the recognition of overwork as a cause of serious illness in Japanese law.