Order in the Assembly: How Japan's High Court Defined "Lawful" Public Duty

The crime of Obstruction of Performance of Public Duty exists to protect the smooth functioning of the state. It is a bedrock principle that citizens cannot use violence or intimidation to prevent public officials from carrying out their lawful responsibilities. But what if the official's act is not entirely lawful? If a police officer conducts a search with a procedural error, or a parliamentary speaker violates a rule of debate, can a citizen legally obstruct that act? Where does the law draw the line between a protected official duty and an unlawful act that may be resisted?

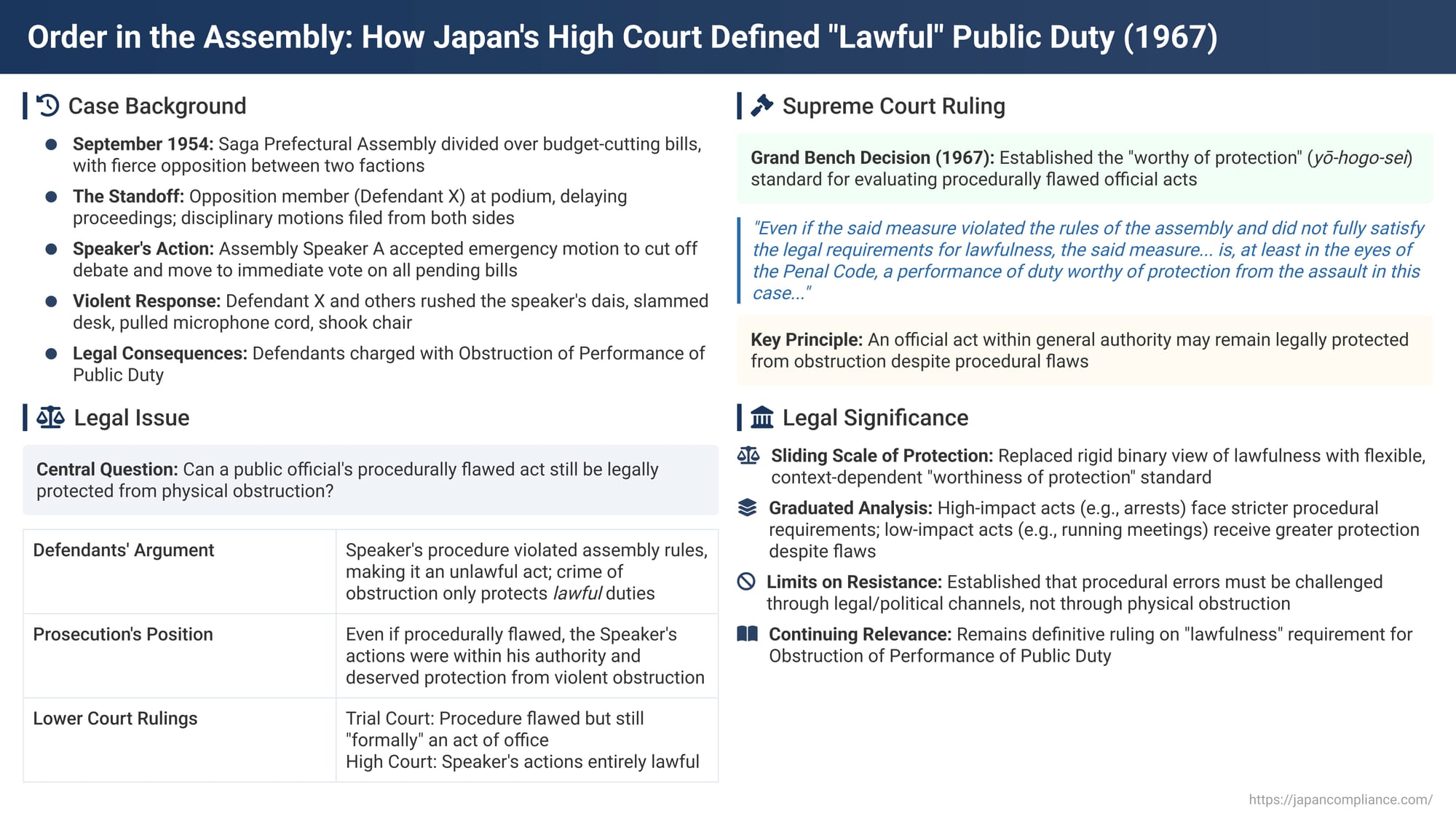

This fundamental question of what constitutes a "lawful" duty was addressed by the full Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan in a dramatic case from 1967. The ruling, which stemmed from a chaotic brawl on the floor of a prefectural assembly, established the crucial concept that a procedurally flawed official act may still be "worthy of protection" (yō-hogo-sei) from violent interference, a standard that continues to define the limits of this crime today.

The Facts: Chaos in the Prefectural Assembly

The case arose from a fiercely contested session of the Saga Prefectural Assembly in September 1954.

- The Political Climate: The assembly was deeply divided into two factions—"proponents" and "opponents"—over a series of budget-cutting bills. The opponents were determined to block the bills, while the proponents were equally determined to pass them, leading to an extremely tense atmosphere.

- The Standoff: On September 18, an opposition member, Defendant X, was at the podium engaged in questioning, part of a broader strategy to delay the proceedings. The proponent faction responded by submitting a disciplinary motion against X. The opposition then filed a counter-motion against a proponent member. Citing an assembly rule that disciplinary motions must be addressed immediately, X refused to continue his questioning and insisted that the disciplinary motions be handled first.

- The Speaker's Controversial Move: In response to this gridlock, the proponent faction introduced an emergency motion to cut off all further questioning and debate and to move to an immediate, en-bloc vote on all the pending bills. Over the protests of the opposition, the Assembly Speaker, A, declared this emergency motion passed by majority vote and attempted to proceed with the final vote on the budget bills.

- The Violent Obstruction: Believing the speaker's procedure to be improper and illegal, Defendant X and four other opposition members rushed the speaker's dais to stop the vote. In the ensuing melee, they slammed their hands on the speaker's desk, tilted it to make it unusable, pulled his microphone cord, and grabbed and shook his chair. These acts of violence physically prevented Speaker A from conducting the vote. X and others were subsequently charged with Obstruction of Performance of Public Duty.

The Legal Defense: Resisting an Unlawful Act

The core of the defendants' argument was that the Speaker's actions—particularly cutting off debate and moving to an en-bloc vote—were a violation of the assembly's own procedural rules and therefore constituted an unlawful performance of his duty. Since the crime of obstruction only protects lawful duties, they argued, one cannot be guilty of obstructing an unlawful act. The trial court found that the speaker's procedure was indeed flawed but convicted the defendants anyway, reasoning that it was still "formally" an act of his office. The High Court went further, finding the speaker's actions to be entirely lawful and upholding the convictions.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling: The "Worthy of Protection" Standard

The Supreme Court Grand Bench upheld the convictions, but in doing so, it introduced a new and more nuanced legal standard. The Court's judgment held:

"The measure taken by the Speaker in this case clearly falls within the abstract authority of the Speaker. Even if the said measure violated the rules of the assembly and did not fully satisfy the legal requirements for lawfulness, the said measure, taken under the concrete factual circumstances found by the court below, is, at least in the eyes of the Penal Code, a performance of duty worthy of protection from the assault in this case, and it is appropriate to view it as the performance of a public official's duty under Article 95, Paragraph 1 of the Penal Code.** Obstructing this act, therefore, does not preclude the establishment of the crime of Obstruction of Performance of Public Duty."

Analysis: A Sliding Scale of Lawfulness

This ruling was immensely significant because it replaced a rigid, black-and-white view of legality with a flexible, context-dependent analysis centered on the concept of "worthiness of protection."

For a public official's act to be considered lawful, it must generally satisfy three conditions: (1) it must be within their general or abstract authority; they must have the specific authority to act in the particular situation; and (3) it must follow important legal procedures. This case focused on the third condition, establishing that a procedural flaw does not automatically render the entire act "unlawful" and therefore unprotected.

Legal scholars suggest that the "worthiness of protection" should be judged on a sliding scale depending on the nature of the official's act and the importance of the violated procedure.

- High-Impact Acts (e.g., Arrest): When an official's action severely infringes on fundamental human rights, such as physical liberty, procedural rules are considered "strict regulations" (genkaku kitei). A significant procedural violation—such as failing to present a warrant when requested—will cause the act to lose its legal protection.

- Low-Impact Acts (e.g., Running a Meeting): When the act, like conducting a debate or performing desk work, does not involve physical force or a major infringement on rights, the official's duty has a high degree of protection. A procedural flaw in this context does not justify violent obstruction. The proper remedy for such a flaw is through debate, political processes, or a subsequent legal challenge, not physical force.

- Application to the Assembly Case: The speaker's actions in this case clearly fall into the second category. His procedurally questionable decision did not physically harm the defendants or deprive them of a fundamental right in a way that would necessitate a physical response. The commentary also notes the context: the opposition's own delay tactics had provoked the speaker's heavy-handed maneuver, weakening their claim that their violent reaction was justified.

Given these circumstances, the Speaker's flawed performance of his duty was still "worthy of protection" from the defendants' violent assault.

Conclusion

The 1967 Grand Bench decision remains the definitive ruling on the "lawfulness" requirement for the crime of Obstruction of Performance of Public Duty. It established the vital principle that not every procedural error renders an official's act "unlawful" and open to physical obstruction. An act that is within an official's general authority and does not gravely infringe upon fundamental rights may still be "worthy of protection," even if it is procedurally imperfect. The ruling reinforces a core tenet of a society governed by the rule of law: the proper response to a perceived procedural error by a public official is not violence, but recourse to the legal and political processes designed to ensure accountability.