Opportunity to Appeal Matters: Japanese Supreme Court on Procedural Fairness in Recognizing Foreign Judgments

Date of Judgment: January 18, 2019

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

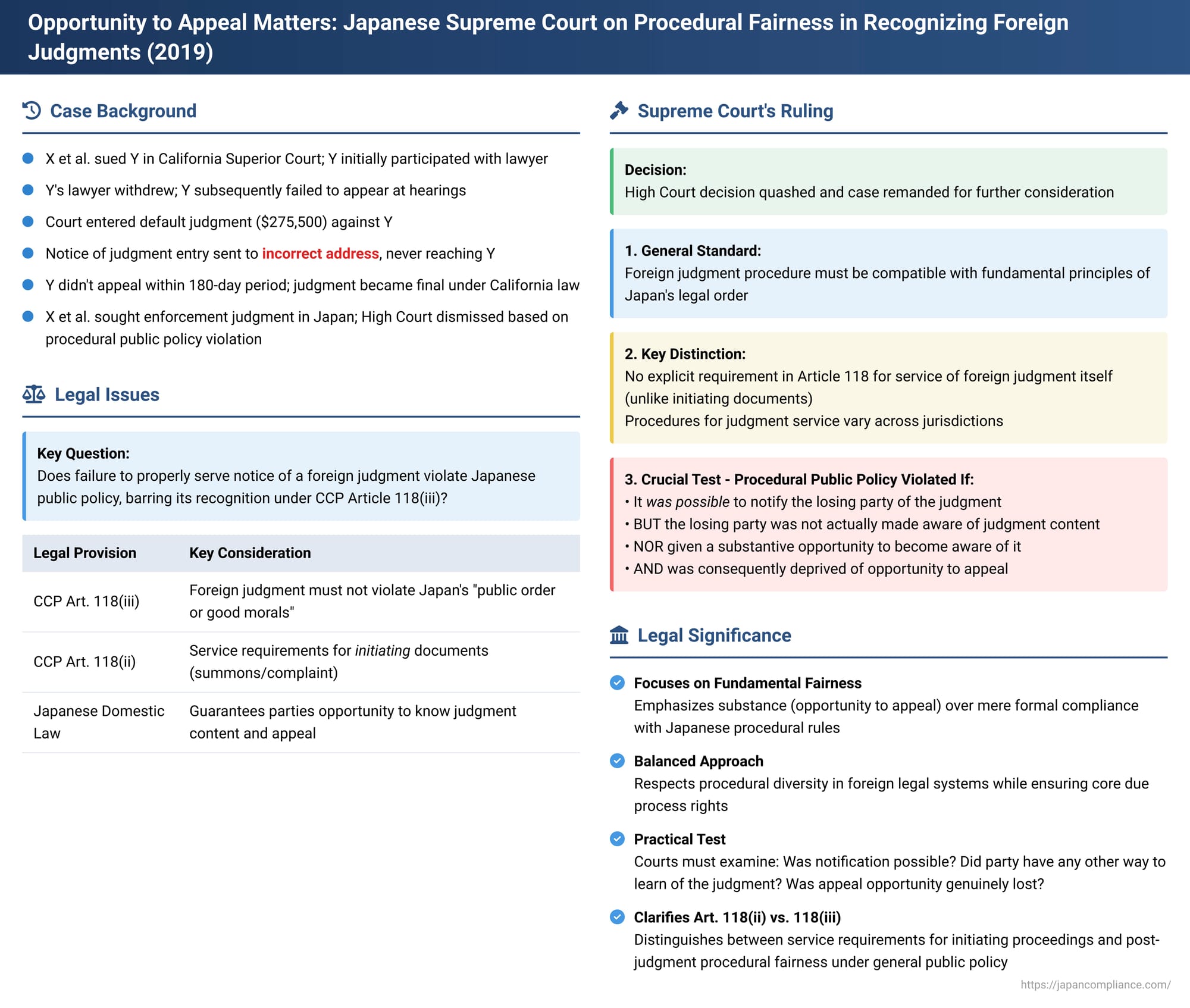

The recognition and enforcement of foreign court judgments is a critical aspect of international legal cooperation. In Japan, Article 118 of the Code of Civil Procedure (CCP) outlines the conditions a foreign judgment must satisfy to be given effect. Among these conditions is that the judgment's content and the procedure by which it was obtained must not be contrary to Japan's "public order or good morals." A Supreme Court decision on January 18, 2019, delved into this "procedural public policy," clarifying when a failure to properly notify a party of the foreign judgment itself—thereby potentially compromising their ability to appeal—can render that judgment unenforceable in Japan.

The Factual Background: A U.S. Default Judgment and Disputed Notice

The case arose from a lawsuit in California:

- X et al. (Plaintiffs/Appellants in the Supreme Court): Had initiated a damages claim against Y (Defendant/Appellee in the Supreme Court) and several others in the Orange County Superior Court, California ("the Foreign Court").

- Y's Initial Participation and Lawyer's Withdrawal: Y initially appointed a lawyer and participated in the U.S. proceedings. However, at a certain point, Y's lawyer was permitted by the Foreign Court to withdraw from the case.

- Y's Subsequent Default: Y failed to appear at subsequent court hearings. As a result, upon X et al.'s motion, Y was registered as being in default for failing to proceed with the litigation.

- The California Default Judgment ("Foreign Judgment"): The Foreign Court, again upon X et al.'s motion, issued a default judgment against Y, ordering Y to pay approximately $275,500. This judgment was duly registered with the Foreign Court.

- Under Californian civil procedure, judgments are registered with the court, and typically, one party serves the other with a "notice of entry of judgment." The period to appeal a judgment generally expires, at the latest, 180 days from the date of its entry.

- Defective Service of the Notice of Entry of Judgment: X et al.'s legal representatives attempted to notify Y of the Foreign Judgment by sending a copy of the judgment and a notice of its entry via ordinary mail. However, this notice was dispatched to an incorrect address for Y. The Supreme Court noted that it could not be said that this notification ever reached Y.

- Finality of the Foreign Judgment: Y did not file an appeal within the 180-day period following the entry of the Foreign Judgment, nor did Y pursue any other avenues for challenging the judgment within the prescribed time limits. Consequently, the Foreign Judgment became final under California law.

- Enforcement Action in Japan: X et al. then initiated legal proceedings in Japan, seeking an enforcement judgment to compel Y to pay the sum awarded by the Foreign Judgment.

The first instance court in Japan partially granted the enforcement. However, the Tokyo High Court, on appeal, dismissed X et al.'s claim entirely. The High Court reasoned that the failure to properly serve Y with notice of the Foreign Judgment itself (which impacted Y's ability to appeal) constituted a violation of procedural public policy under Article 118(iii) of the CCP. X et al. appealed this dismissal to the Supreme Court.

The Core Legal Question: Does Failure to Properly Serve Notice of a Foreign Judgment Violate Japanese Public Policy, Barring Its Recognition?

The central issue for the Supreme Court was whether the defective notification of the judgment itself to Y, and the potential impact on Y's opportunity to appeal in California, rendered the Foreign Judgment's enforcement contrary to Japan's public policy.

The Supreme Court's Key Rulings on Procedural Public Policy (CCP Art. 118(iii))

The Supreme Court quashed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further consideration, providing important clarifications on procedural public policy:

1. General Standard for Public Policy:

The Court reiterated its established principle (citing its 1997 decision on punitive damages, see case 96 in this series) that for a foreign judgment to be denied recognition on public policy grounds under CCP Art. 118(iii), its content or the procedure by which it was obtained must be incompatible with the fundamental principles or basic ideals of Japan's legal order. The mere fact that the foreign proceedings involved legal systems or rules not adopted in Japan is not, by itself, sufficient to constitute a public policy violation.

2. Service of the Judgment Itself vs. Service of Initiating Documents:

The Supreme Court drew a distinction regarding service requirements under Article 118:

- Service of Initiating Documents (Art. 118(ii)): This provision explicitly requires that the losing defendant either received proper service of the summons or order necessary for the commencement of the foreign proceedings, or appeared in those proceedings. This focuses on ensuring the defendant is aware of the lawsuit from the outset.

- Service of the Judgment: In contrast, Article 118 contains no explicit requirement for the service of the foreign judgment itself on the losing party as a condition for its recognition in Japan.

- Diversity of Foreign Procedures: The Court acknowledged that procedures concerning the service of judgments vary significantly from one jurisdiction to another.

- Conclusion on Lack of Judgment Service Per Se: Therefore, the mere fact that a foreign judgment was not served on the losing party (in a manner that might be required under Japanese domestic law, for instance) does not, by itself, automatically mean that the foreign proceedings violate Japanese public policy under Article 118(iii).

3. The Crucial Test: Substantive Opportunity to Know the Judgment and Appeal:

While non-service of the judgment isn't an automatic bar, the Supreme Court identified a more fundamental principle at stake:

- Japanese civil procedure, as a core tenet, guarantees parties a substantive opportunity to be made aware of the content of a judgment rendered against them, thereby ensuring they have a meaningful opportunity to appeal that judgment (except in cases where direct notification is impossible, e.g., due to unknown whereabouts allowing for service by publication).

- Therefore, a foreign judgment's procedure will be considered contrary to Japan's public policy under Article 118(iii) if:

- It was possible for the foreign court or the winning party to make the losing party aware of the content of the foreign judgment;

- BUT, in reality, the losing party was not actually made aware of the judgment's content, NOR were they given a substantive opportunity to become aware of it; AND

- As a result of this lack of awareness or opportunity, the losing party was deprived of their opportunity to file an appeal or other challenge before the foreign judgment became final.

Application to the Case and Remand

The Supreme Court found that the Tokyo High Court had erred in its application of the public policy principle. The High Court had seemingly concluded that the defective service of the notice of entry of judgment automatically violated public policy, without thoroughly examining whether Y was, in fact, completely deprived of any substantive opportunity to learn of the judgment and appeal it, particularly given that it might have been possible for X et al. to properly notify Y.

The Supreme Court, therefore, remanded the case to the Tokyo High Court. The High Court was directed to further examine the factual circumstances surrounding Y's awareness (or lack thereof) of the Foreign Judgment, specifically focusing on:

- Whether it was indeed possible for X et al. to have properly notified Y of the judgment's content.

- Whether Y, despite the faulty mailing of the notice, actually became aware or had a substantive opportunity to become aware of the judgment's content through other means.

- Ultimately, whether Y was consequently denied a genuine opportunity to appeal the Californian judgment before it became final.

Significance and Commentary Insights

This 2019 Supreme Court decision provides vital clarification on the application of procedural public policy when recognizing foreign judgments in Japan:

- Focus on Fundamental Fairness: The ruling underscores that Japan's public policy review, while respecting procedural diversity in foreign legal systems, will not tolerate outcomes that violate fundamental procedural guarantees, such as the substantive opportunity to know of a judgment and to seek an appeal.

- Not Mere Formalism: The decision moves beyond a purely formalistic check of whether Japanese service rules were followed for the foreign judgment. Instead, it mandates a more substantive inquiry into whether the party was genuinely deprived of their appellate rights due to a lack of notice, when such notice was feasible.

- Distinction from Service of Initiating Documents (Art. 118(ii)): The Court deliberately rooted its analysis in the general public policy clause (Art. 118(iii)) rather than the specific clause on service of initiating documents (Art. 118(ii)). This is because Art. 118(ii) is primarily concerned with ensuring the defendant is aware of the lawsuit at its commencement. Procedural fairness after judgment is rendered but before appeal rights expire falls under the broader public policy assessment. Academic commentary, such as by Professor Haga, notes ongoing discussion about the precise interplay and boundaries between these two sub-clauses in ensuring overall procedural fairness.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision in this case refines the understanding of procedural public policy in the context of foreign judgment recognition in Japan. It establishes that while foreign judicial procedures do not need to mirror Japan's, they must not fundamentally compromise a party's ability to exercise essential procedural rights, such as the opportunity to be informed of a judgment and to pursue an appeal. A failure in the foreign proceedings to provide such a substantive opportunity, when it was otherwise possible, can lead to the non-recognition of the foreign judgment in Japan on the grounds that it violates the basic principles of Japan's legal order. This ruling emphasizes a commitment to due process, even when evaluating the outcomes of legal proceedings from other jurisdictions.