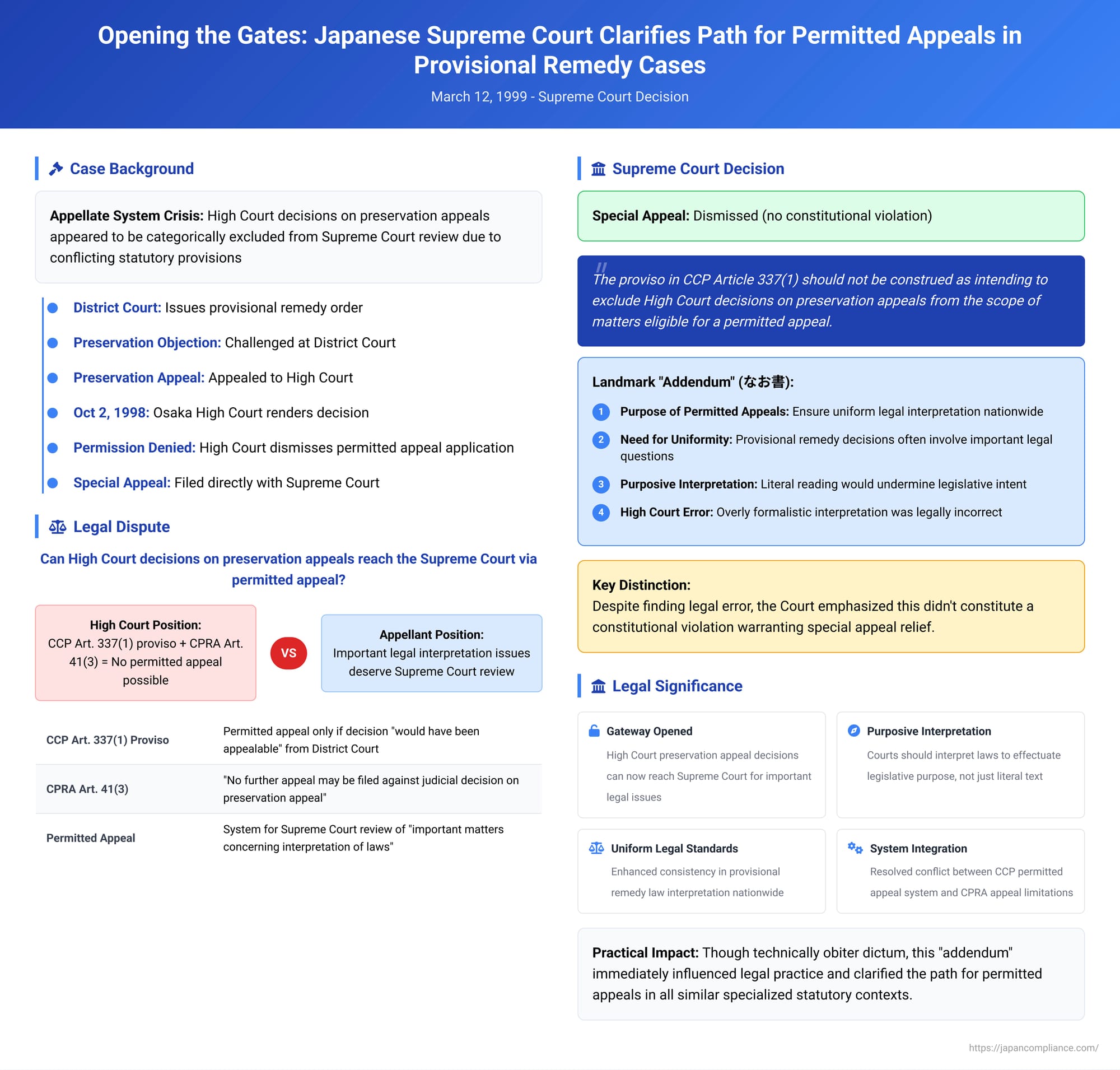

Opening the Gates: Japanese Supreme Court Clarifies Path for Permitted Appeals in Provisional Remedy Cases

Date of Supreme Court Decision: March 12, 1999

The Japanese judicial system, like many others, has specific pathways for appealing lower court decisions, with appeals to the Supreme Court being subject to particular restrictions. One such avenue is the "permitted appeal" (許可抗告 - kyoka kōkoku), a system primarily designed to allow the Supreme Court to address important matters of legal interpretation to ensure nationwide uniformity. However, the precise scope of this system, particularly concerning decisions in civil provisional remedy cases, faced a significant interpretive challenge. A 1999 Supreme Court decision (Heisei 10 (Ku) No. 699) provided crucial clarification, effectively ensuring that important legal questions arising from provisional remedy proceedings could indeed reach the nation's highest court.

The Procedural Labyrinth: From Provisional Order to a Quest for Supreme Court Review

Civil provisional remedies (保全命令 - hozen meirei), such as provisional attachments or dispositions, are interim measures issued by courts to protect a party's rights pending a final resolution of a dispute. The typical procedural path often involves:

- A District Court issuing an initial provisional remedy order.

- The aggrieved party filing a "preservation objection" (保全異議 - hozen igi) with the same District Court, seeking revocation or modification of the order.

- Following the District Court's decision on the preservation objection, either party can file a "preservation appeal" (保全抗告 - hozen kōkoku) to the competent High Court.

The Civil Provisional Remedies Act (CPRA), in Article 41, Paragraph 3, generally stipulates that "no further appeal may be filed against a judicial decision on a preservation appeal." This provision establishes a two-instance system (District Court to High Court) as the standard appellate route for these interim measures, aiming for swift resolution.

The present case reached the Supreme Court after a High Court had rendered a decision on such a preservation appeal. The party dissatisfied with the High Court's decision sought to appeal further to the Supreme Court via the "permitted appeal" route under Article 337 of the Code of Civil Procedure (CCP). This article allows a party to seek permission from the High Court (or, in some cases, from the Supreme Court itself) to appeal a High Court decision or order if it contains "important matters concerning the interpretation of laws and regulations."

However, Article 337, Paragraph 1 of the CCP includes a critical proviso: a High Court decision is eligible for a permitted appeal only if "the judicial decision would have been appealable had it been a judicial decision of a district court."

The High Court's Dilemma and Decision:

The Osaka High Court, when faced with the application for permission to appeal its own decision on the preservation appeal (issued on October 2, 1998), found itself in an interpretive bind. It reasoned:

- If its current decision on the preservation appeal had hypothetically been rendered by a District Court, then CPRA Article 41, Paragraph 3 ("no further appeal may be filed against a judicial decision on a preservation appeal") would clearly prohibit any further ordinary appeal.

- Therefore, the condition set forth in the proviso of CCP Article 337, Paragraph 1 was not met.

Consequently, the High Court dismissed the application for permission to appeal to the Supreme Court as being procedurally improper.

The appellant then filed a "special appeal" (特別抗告 - tokubetsu kōkoku) directly with the Supreme Court against the High Court's decision dismissing the application for permission to appeal. Special appeals under CCP Article 336 are generally restricted to challenging lower court decisions on the grounds of an alleged constitutional violation.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Dismissal of Special Appeal but a Landmark "Addendum"

The Supreme Court, in its decision of March 12, 1999, first addressed the special appeal itself.

- Dismissal of the Special Appeal: The Court dismissed the special appeal. It found that the appellant's arguments, while framed as asserting a constitutional violation, were in substance merely challenging the High Court's interpretation of ordinary statutes (the CCP and CPRA). Such ordinary legal errors, the Court held, do not satisfy the stringent criteria for a special appeal.

However, the Supreme Court did not stop there. It included an extremely important "addendum" (なお書 - naogaki) to its decision, which provided a definitive interpretation of the seemingly conflicting statutory provisions.

The Crucial "Naogaki" (Addendum) – Reinterpreting the Path for Permitted Appeals:

- Purpose of the Permitted Appeal System (CCP Art. 337): The Supreme Court began by underscoring the legislative purpose behind the permitted appeal system. This system, introduced by the comprehensive reforms to the Code of Civil Procedure in 1996 (effective 1998), was specifically created to ensure the uniform interpretation of laws and regulations across Japan. It provides a mechanism for the Supreme Court to review certain High Court decisions and orders that involve important matters of legal interpretation, even if they don't raise direct constitutional issues. This was intended to address a previous gap where conflicting interpretations among different High Courts on significant legal points (especially those decided by "orders" rather than full "judgments") might not otherwise receive Supreme Court scrutiny.

- Need for Uniformity in Provisional Remedy Cases: The Court explicitly recognized that decisions rendered by High Courts on preservation appeals in civil provisional remedy cases often contain important questions of legal interpretation. The necessity for uniform interpretation in this field is just as significant as it is for decisions on, for example, execution appeals in civil enforcement cases.

- Purposive Interpretation of CCP Article 337, Paragraph 1 Proviso: This was the core of the addendum. The Supreme Court declared that, in light of the aforementioned legislative purpose of the permitted appeal system (i.e., to achieve uniform legal interpretation), the proviso in CCP Article 337, Paragraph 1 should not be construed as intending to exclude High Court decisions on preservation appeals from the scope of matters eligible for a permitted appeal.

- High Court's Interpretive Error: Based on this purposive interpretation, the Supreme Court stated that the Osaka High Court's original reasoning for dismissing the application for permission to appeal (which was based on a literal and formalistic reading of the CCP proviso in conjunction with CPRA Article 41(3)) constituted an erroneous interpretation of the law.

Despite finding this legal error in the High Court's reasoning, the Supreme Court reiterated that this error did not rise to the level of a constitutional violation that would justify allowing the special appeal.

Understanding the Legal Framework and the Supreme Court's Reasoning

This decision is best understood in the context of the Japanese appellate structure and the goals of its procedural laws:

- Limited Appeals to the Supreme Court: The Supreme Court of Japan's role is primarily focused on constitutional matters and ensuring the uniform interpretation of laws, rather than serving as a general third instance for error correction in all cases.

- The Permitted Appeal System (許可抗告制度 - kyoka kōkoku seido): This system was a key innovation of the 1996 Code of Civil Procedure reforms. It was designed to allow the Supreme Court to selectively review High Court decisions (that are not final judgments subject to ordinary appeal) if they contain important legal interpretive issues, thereby promoting consistency in the application of law nationwide. This was particularly important for areas governed by specialized statutes like the Civil Execution Act and the Civil Provisional Remedies Act, where many critical legal points are decided by court "orders" or "decisions" rather than full-fledged "judgments."

- The Apparent Conflict:

- CCP Art. 337(1) Proviso: Limited permitted appeals from High Court decisions to those that would have been appealable if made by a District Court.

- CPRA Art. 41(3): States that decisions on "preservation appeals" (which are typically appeals from a District Court's decision on a provisional remedy to a High Court) are generally final, with no further ordinary appeal.

- The High Court's Literal Logic: If a High Court decision on a preservation appeal were hypothetically a District Court decision on the same matter, CPRA Art. 41(3) would seem to bar any further appeal from it. Thus, the High Court concluded, such decisions don't meet the CCP proviso's condition.

- The Supreme Court's Purposive (Teleological) Interpretation: The Supreme Court looked beyond the literal wording to the underlying purpose of the permitted appeal system. It recognized that a strict, literal application of the proviso would effectively bar many, if not all, High Court decisions in provisional remedy cases from ever being reviewed by the Supreme Court through the permitted appeal route. This would undermine the very goal of ensuring uniform legal interpretation for important issues frequently arising in these specialized and often urgent proceedings (e.g., questions about the "necessity of preservation," appropriate methods of provisional relief, etc., which are not typically re-litigated in the main substantive lawsuit).

- Addressing a Potential "Legislative Oversight": Legal commentators had noted this potential conflict shortly after the 1996 CCP reforms. Some suggested that the drafters of the CCP might not have fully anticipated this specific interaction with the CPRA, or that it represented a "gap in the law." The Supreme Court's decision, through its purposive interpretation, effectively addressed this issue, ensuring that the permitted appeal system could function as intended for provisional remedy cases.

Implications of the Supreme Court's "Addendum"

Although technically obiter dictum (remarks not strictly essential to the decision on the special appeal itself), the Supreme Court's "addendum" in this case had a profound and immediate impact on legal practice:

- Opened the Gateway for Permitted Appeals in Provisional Remedy Cases: It served as a clear directive to High Courts and legal practitioners that High Court decisions on preservation appeals are indeed eligible for the permitted appeal route to the Supreme Court, provided they involve important matters of legal interpretation that warrant Supreme Court review for the sake of uniformity.

- Prioritization of Uniform Legal Interpretation: The decision strongly emphasized the Supreme Court's role and commitment to maintaining consistency in how laws are interpreted and applied throughout the nation, extending this principle robustly into the specialized field of civil provisional remedies.

- Broader Application: Legal scholarship suggests that the reasoning in this decision would likely apply to other analogous situations under the CPRA where a two-instance appeal structure might superficially appear to conflict with the CCP Article 337(1) proviso. This includes, for instance, High Court decisions on immediate appeals concerning the issuance of provisional orders themselves (CPRA Art. 19(2)) or certain other appeals under CPRA Art. 41(1) proviso.

Concluding Thoughts

While the specific special appeal in the Heisei 10 (Ku) No. 699 case was dismissed on narrow grounds, the Supreme Court seized the opportunity to issue a landmark interpretive guideline in its "addendum." By adopting a purposive interpretation of the Code of Civil Procedure's provisions for permitted appeals, the Court ensured that crucial legal questions arising from High Court decisions in civil provisional remedy cases would not be categorically excluded from its review. This decision was instrumental in aligning the procedural rules with the overarching legislative goal of promoting uniform legal interpretation by Japan's highest court, thereby enhancing the predictability and coherence of the law in the vital area of provisional remedies. It stands as a significant example of the judiciary's role in interpreting statutes in a manner that effectuates their underlying purpose, even when faced with apparent textual complexities.