Open Records, Shifting Reasons: Supreme Court on Justifying Non-Disclosure in Japan

Judgment Date: November 19, 1999

Case Number: Heisei 8 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 236 – Claim for Revocation of Partial Non-Disclosure of Public Documents

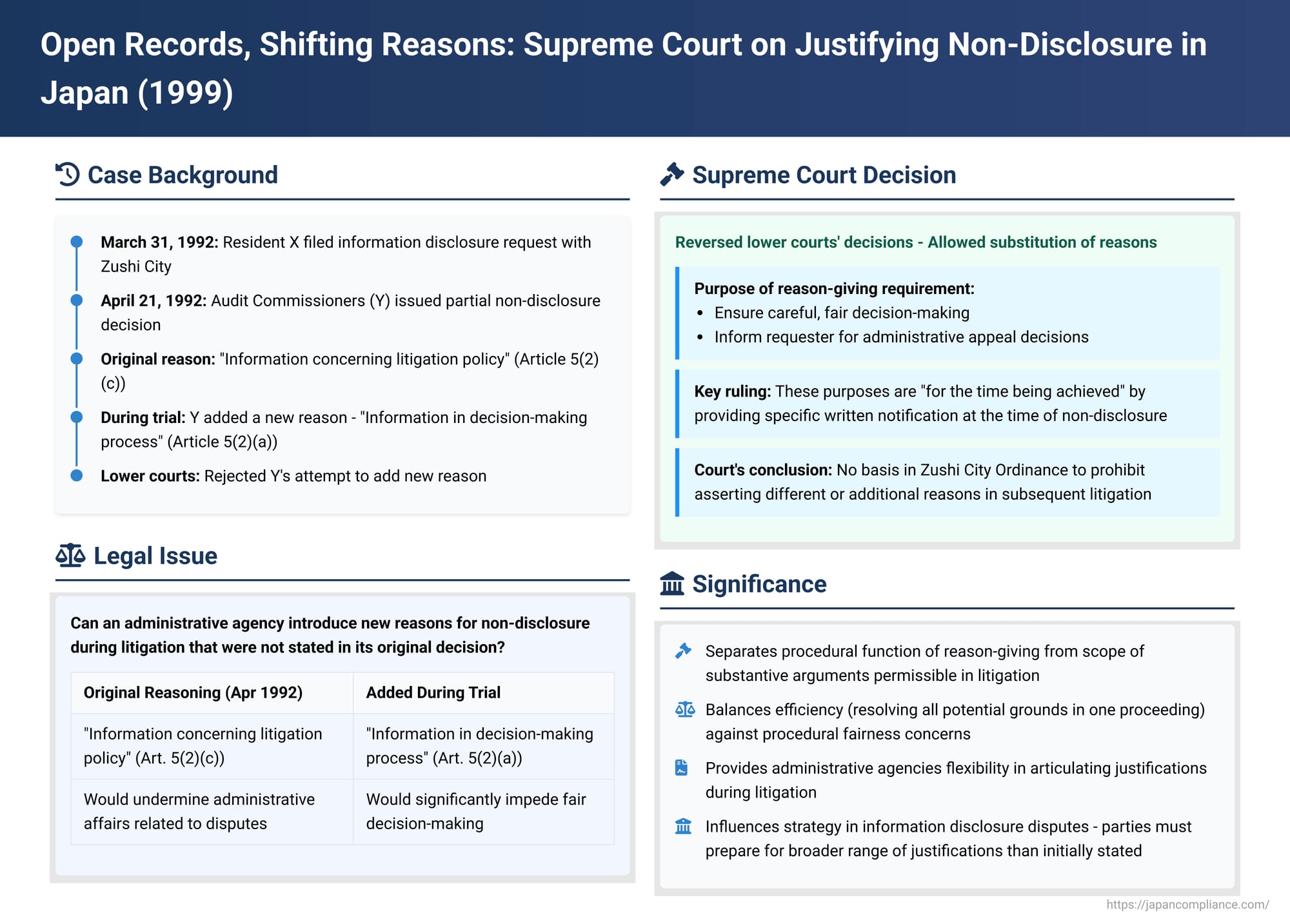

Information disclosure laws are a cornerstone of transparent governance, allowing citizens to access official documents. However, when a government agency denies access, it is typically required to provide reasons for its decision. This raises a crucial question: if a citizen challenges that denial in court, can the agency introduce new reasons for withholding the information that weren't stated in its original decision? A 1999 Japanese Supreme Court decision addressed this issue of "substitution of reasons" in the context of an information disclosure request made under a local ordinance.

The Zushi City Information Request

The case began on March 31, 1992, when X, a resident of Zushi City, filed a request under the Zushi City Information Disclosure Ordinance (at the time) for access to all records concerning residents' audit requests submitted in 1984 and 1985. The Zushi City Audit Commissioners (Y), the implementing agency under the ordinance, responded on April 21, 1992, with a decision to partially withhold some of the requested documents. Specifically, Y decided not to disclose records of interviews conducted with relevant individuals.

The original reason provided by Y for this non-disclosure was that the information fell under Article 5, Paragraph 2, Subparagraph (c) of the Zushi City Ordinance, which exempted "information concerning litigation policy" whose disclosure would allegedly undermine the objectives of, or severely hinder, the smooth execution of administrative affairs related to disputes, or future similar affairs.

X pursued administrative appeals against this decision (an appeal to the Information Disclosure Review Board and an objection to Y), but these were rejected. X then filed a lawsuit seeking the revocation of Y's non-disclosure decision.

A New Justification Emerges in Court

During the court proceedings, Y (the Zushi City Audit Commissioners) introduced an additional reason to justify withholding the documents. Y argued that the records also constituted "information in the process of decision-making" under Article 5, Paragraph 2, Subparagraph (a) of the Ordinance. This provision exempted information related to internal deliberations, research, studies, etc., if its disclosure would significantly impede fair or appropriate decision-making.

The lower courts—the Yokohama District Court (first instance) and the Tokyo High Court (second instance)—rejected Y's attempt to add this new reason. They held that, considering the spirit and objectives of the Information Disclosure Ordinance, allowing the agency to substitute or supplement the reason originally provided in the non-disclosure notice with a new, previously unstated reason was impermissible. Y then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Reversal (November 19, 1999)

The Supreme Court overturned the decisions of the lower courts and remanded the case back to the Tokyo High Court for further consideration. The Court ruled that Y was permitted to raise the additional non-disclosure reason in court.

Why Substitution Was Allowed: The Purpose of Reason-Giving Revisited

The Supreme Court's reasoning focused on the underlying purpose of the reason-giving requirement stipulated in Article 9, Paragraph 4 of the Zushi City Ordinance:

- Primary Goals of Reason-Giving: The Court stated that the requirement for an agency to notify the requester of the reasons for non-disclosure serves two main purposes:

- To ensure that the agency's decision-making process is careful, fair, and appropriate, thereby curbing arbitrariness.

- To inform the requester of the grounds for refusal, which facilitates their ability to make an informed decision about whether and how to pursue an administrative appeal.

- These Goals are Met by the Initial Notice: The Supreme Court found that these purposes are "for the time being achieved" (hitomazu jitsugen sareru) by the very act of providing a specific, written notification of the reasons at the time of the non-disclosure decision.

- No Implied Prohibition on Asserting Other Reasons in Court: The Court found no basis in the Zushi City Ordinance's provisions to interpret the reason-giving requirement as extending beyond these initial procedural purposes. Specifically, there was no ground to conclude that once an agency has stated reasons in its initial notice, it is thereafter barred from asserting different or additional reasons in a subsequent court action challenging that non-disclosure decision.

Therefore, the lower courts had erred in law by concluding that Y was precluded from arguing that the documents fell under Article 5(2)(a) (decision-making process information) simply because this was not the reason given initially. The Supreme Court also found that the High Court had interpreted both exemption clauses (Art. 5(2)(c) and Art. 5(2)(a)) too narrowly and directed it to re-examine the documents based on a broader understanding of these exemptions.

Implications and Scholarly Discussion

This 1999 Supreme Court decision allowing the substitution of reasons in an information disclosure case has generated considerable discussion:

- Identity of the Disposition: Generally, substituting one non-disclosure reason for another (e.g., from "litigation policy" to "decision-making process") for the same set of documents does not usually change the fundamental identity of the administrative act being challenged, which remains the "decision to not disclose these specific documents". This is distinct from a situation like a disciplinary punishment for a public servant, where changing the alleged misconduct (e.g., from a traffic violation to leaking secrets) would likely constitute a different処分.

- Reason-Giving as a Procedural Safeguard: The judgment effectively separates the initial procedural function of reason-giving (ensuring careful agency deliberation and informing the applicant) from the scope of substantive arguments permissible in subsequent litigation. While the initial reasons fulfill an immediate purpose, they don't necessarily freeze the agency's legal justifications for all time.

- Efficiency vs. Procedural Fairness: Allowing reason substitution might promote efficiency by enabling a court to consider all potential grounds for non-disclosure in a single proceeding, leading to a more definitive resolution. However, it also raises concerns about procedural fairness. If an applicant litigates based on the initially stated reasons, only to be confronted with new ones later, they might be caught off guard, and the value of prior administrative appeal proceedings focused on the original reasons could be diminished.

- Nature of Information Disclosure Law: Some commentators argue that the very nature of information disclosure laws, which aim to promote transparency and government accountability, might call for stricter adherence to initially stated reasons. This would encourage agencies to conduct thorough reviews and articulate all applicable exemptions from the outset. The Supreme Court, in this instance, did not adopt such a stringent interpretation.

- Context of Application Refusals: In the broader context of refusals of applications (as opposed to punitive actions), some argue that allowing reason substitution might be more beneficial to the applicant if it leads to a quicker, comprehensive resolution in court, rather than the case being sent back to the agency to issue a new refusal on different grounds, thereby prolonging the process.

- Impact of Third-Party Interests: An important consideration is whether this ruling's permissiveness would extend to cases where the substituted reasons involve different categories of sensitive information, such as personal privacy or confidential corporate data, which often have their own specific procedural safeguards and third-party notification requirements. The Zushi case primarily involved "administrative execution information" (internal government information related to litigation and decision-making) rather than direct third-party privacy concerns.

- Modern Litigation Practice: In contemporary information disclosure litigation in Japan, it's common for a lawsuit to revoke a non-disclosure decision to be filed alongside an "obligation-to-disclose lawsuit" (gimuzuke soshō), compelling the agency to release the information. In such combined proceedings, courts tend to examine all possible non-disclosure grounds asserted by the agency, making the issue of sequential reason substitution less central.

Concluding Thoughts

The 1999 Supreme Court decision in the Zushi City information disclosure case indicates a judicial inclination to allow administrative agencies a degree of flexibility in articulating their justifications for non-disclosure during litigation. The Court prioritized the notion that the initial reason-giving fulfills its primary procedural purposes at the administrative stage, without estopping the agency from raising other pertinent non-disclosure grounds in a subsequent court challenge. This approach has significant implications for how both citizens requesting information and public bodies responding to such requests strategize and conduct themselves in information disclosure disputes, emphasizing that the legal battle may involve a broader range of justifications than those first stated.