Online Pharmacy Sales and Legislative Limits: Japan's Supreme Court on Vague Delegations

A Second Petty Bench Ruling from January 11, 2013

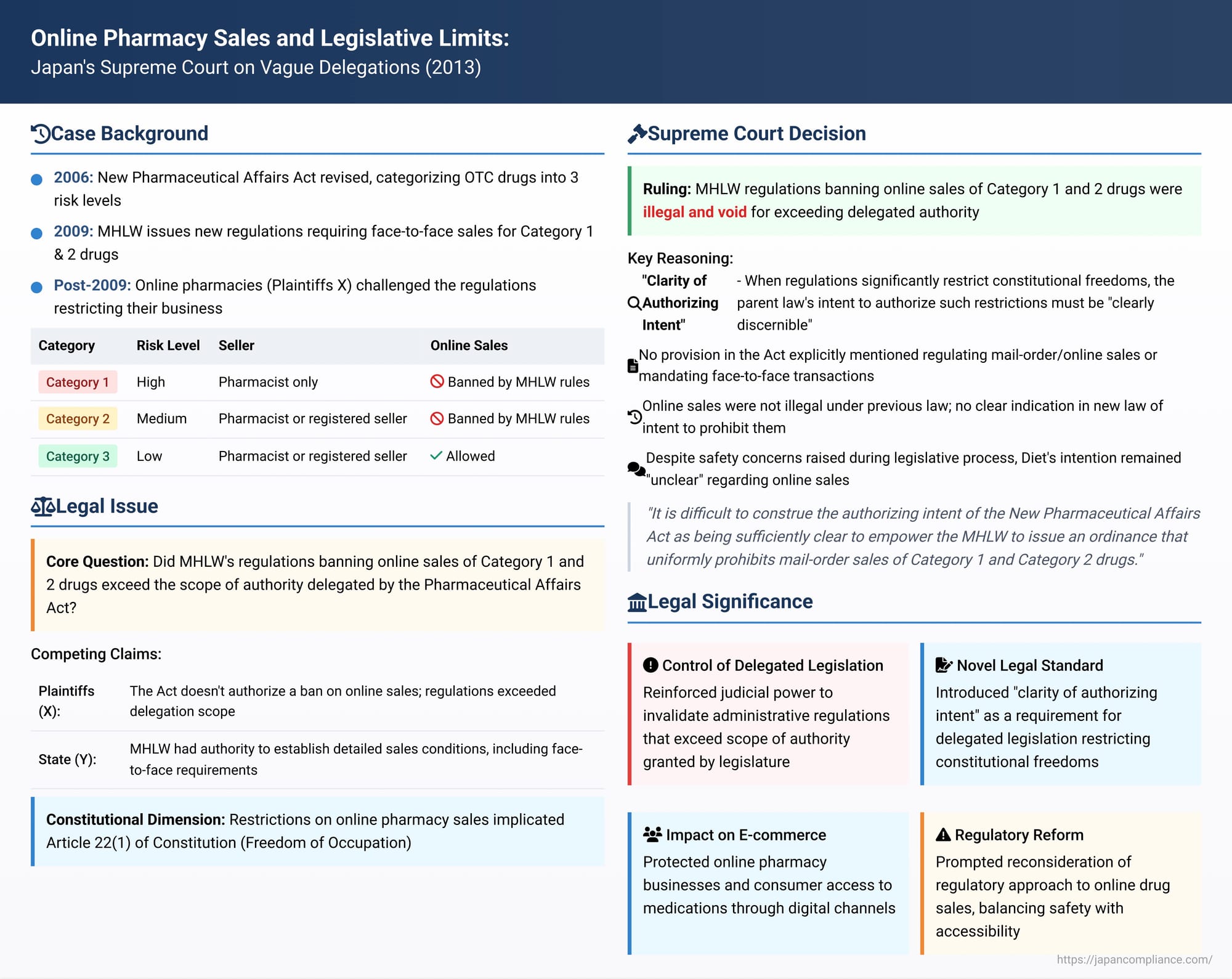

The sale of pharmaceuticals is an area where public safety concerns often intersect with economic freedoms and consumer convenience. Modern governments frequently rely on "delegated legislation"—allowing ministries or agencies to create detailed rules under a framework established by primary laws passed by the legislature. However, a critical constitutional question always looms: how specific must these primary laws be when granting such rule-making authority, especially when the resulting rules significantly impact businesses and consumers? A notable decision by the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on January 11, 2013 (Heisei 24 (Gyo Hi) No. 279), addressed this very issue, scrutinizing Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) regulations that effectively banned the online sale of certain non-prescription drugs.

The Regulatory Shift: From Traditional Sales to Online Restrictions

The case arose following a significant revision to Japan's Pharmaceutical Affairs Act (薬事法 - Yakuji Hō) in 2006. This "New Pharmaceutical Affairs Act" categorized non-prescription (over-the-counter) medicines into three classes based on their potential risks:

- Category 1 drugs: Those with the highest risk among non-prescription drugs, requiring special care in their use.

- Category 2 drugs: Those with moderate risk.

- Category 3 drugs: Those with relatively lower risk.

The New Act stipulated that Category 1 drugs must be sold by a pharmacist, while Category 2 and 3 drugs could be sold by either a pharmacist or a newly established category of professional called a "registered seller" (登録販売者 - tōroku hanbaisha). It also mandated that information be provided to purchasers: by a pharmacist for Category 1 drugs, and by a pharmacist or registered seller (with an effort to provide for Category 2) for Category 2 and 3 drugs. Both the sales and information provision aspects were to be detailed "as prescribed by ministry ordinance".

Subsequently, the MHLW revised its Implementing Rules (Enforcement Regulations of the Pharmaceutical Affairs Act, MHLW Ordinance No. 10 of 2009). These new rules imposed stringent conditions:

- They required that Category 1 and Category 2 drugs be sold or supplied "face-to-face" (taimen) at a physical pharmacy or store (New Implementing Rule 159-14, paragraphs 1 and 2).

- Information regarding these drugs also had to be provided face-to-face within the store premises (New Implementing Rule 159-15, paragraph 1, item 1; Rule 159-17, items 1 and 2).

- Crucially, these requirements effectively prohibited "mail-order sales" (郵便等販売 - yūbin-tō hanbai), a term encompassing internet sales, for both Category 1 and Category 2 drugs (New Implementing Rule 142; Rule 15-4, paragraph 1, item 1). Only Category 3 drugs remained broadly available for online purchase.

The Plaintiffs' Challenge: Online Businesses Fight Back

These new MHLW Implementing Rules had a profound impact on businesses, X et al. (the plaintiffs/appellees), that had been conducting online and mail-order sales of a wide range of pharmaceuticals, including those now classified as Category 1 and 2 drugs. Under the old Pharmaceutical Affairs Act, such sales had not been explicitly illegal, though they were subject to varying degrees of administrative guidance. X et al. filed a lawsuit against the State (Y, the appellant), arguing that the MHLW rules imposing a near-total ban on online sales of Category 1 and 2 drugs were unlawful and void. Their central contention was that these rules went beyond the scope of the regulatory authority delegated to the MHLW by the New Pharmaceutical Affairs Act.

The plaintiffs sought several remedies: confirmation of their right or legal status to continue selling Category 1 and 2 drugs via mail-order despite the new rules (a type of lawsuit known as tōjisha soshō, or party litigation); confirmation of the invalidity of the new MHLW rules; and, alternatively, the annulment of these rules (a type of public law action challenging an administrative disposition, or kōkoku soshō).

The lower courts reached different conclusions. The Tokyo District Court (first instance) acknowledged the admissibility of the claim for confirmation of status but ultimately dismissed it on the merits, finding the MHLW rules to be within the scope of legitimate delegation. However, the Tokyo High Court (second instance) overturned this part of the decision. The High Court emphasized that the new rules significantly restricted the freedom of occupation of businesses engaged in mail-order sales. It meticulously examined the New Pharmaceutical Affairs Act and found no clear provisions indicating a legislative intent to prohibit or restrict such mail-order sales. Therefore, the High Court concluded that the MHLW Implementing Rules, by imposing such a broad ban, had exceeded the scope of authority delegated by the Act and were consequently illegal and void. The State then appealed this ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision of January 11, 2013

The Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court dismissed the State's appeal, thereby upholding the Tokyo High Court's judgment that the MHLW Implementing Rules banning online sales of Category 1 and 2 drugs were invalid.

Core Reasoning: The Need for "Clarity of Authorizing Intent"

The Supreme Court's decision rested on a careful analysis of the relationship between the New Pharmaceutical Affairs Act and the MHLW Implementing Rules:

- Impact on Freedom of Occupation: The Court began by affirming that the guarantee of freedom of occupation under Article 22, paragraph 1 of the Constitution of Japan encompasses not only the freedom to choose an occupation but also the freedom of engaging in occupational activities. It recognized that the new MHLW rules, which effectively banned a form of pharmaceutical sales that was not illegal under the previous iteration of the Act, imposed a "considerable restriction" on the occupational activities of businesses for whom mail-order sales were a central part of their operations.

- The Standard for Valid Delegation: Given these significant restrictions on a constitutionally protected freedom, the Court articulated a key standard: for the MHLW Implementing Rules to be deemed valid—meaning they conform to the purpose of the delegating New Pharmaceutical Affairs Act (as required by Article 38, paragraph 1 of the Administrative Procedure Act) and do not exceed the scope of its delegation—the "authorizing intent" (授権の趣旨 - juken no shushi) of the New Act to permit the creation of such specific regulations (in terms of their scope and degree) must be "clearly discernible" (明確に読み取れる - meikaku ni yomitoreru). This clarity, the Court stated, should be evident from an examination of the various provisions of the New Act, including Articles 36-5 and 36-6, and should also take into account discussions during the legislative process.

- Lack of Clear Authorizing Intent in the New Act: Applying this standard, the Supreme Court scrutinized the New Pharmaceutical Affairs Act and found that such clear authorizing intent was lacking:

- The literal wording (文理 - bunri) of Articles 36-5 (on sales by pharmacists/registered sellers) and 36-6 (on information provision) neither explicitly mentions the regulation of mail-order sales nor mandates that sales, supply, and information provision must occur face-to-face. These articles do not explicitly address the necessity of such restrictions either.

- Article 37, paragraph 1 of the New Act, which pertains to restrictions on methods of selling or supplying drugs, had not been substantially altered from its form under the old Pharmaceutical Affairs Act, a period during which mail-order sales were clearly not illegal.

- The Court found no other provisions within the New Pharmaceutical Affairs Act that clearly indicated an intention to limit the methods of selling or supplying non-prescription drugs (or providing information about them) exclusively to face-to-face interactions at physical stores, or to otherwise regulate (i.e., restrict or prohibit) mail-order sales.

- Despite discussions during the legislative process where concerns about the safety of online sales were raised by some, the Court found it "difficult to say" that the National Diet, when it enacted the New Pharmaceutical Affairs Act, actually possessed the intention to prohibit mail-order sales of Category 1 and Category 2 drugs. The New Act's stance on mail-order sales remained, in the Court's view, "unclear" (fubunmei).

- Conclusion on the Implementing Rules: Based on this analysis, the Supreme Court concluded that it was "difficult to construe" the authorizing intent of the New Pharmaceutical Affairs Act as being sufficiently clear to empower the MHLW to issue an ordinance that uniformly prohibits mail-order sales of Category 1 and Category 2 drugs. Therefore, the MHLW Implementing Rules—specifically those provisions mandating face-to-face sales and information provision for Category 1 and 2 drugs and prohibiting their mail-order sale—to the extent that they resulted in a blanket ban on mail-order sales for these drug categories, were "not in conformity with the purpose of the New Pharmaceutical Affairs Act" and "exceeded the scope of delegation" granted by the Act. As such, these provisions were deemed "illegal and void".

Understanding "Scope of Delegation" in Japanese Administrative Law

This case delves into the critical administrative law principle of "scope of delegation" (委任の範囲 - inin no hani).

- Constitutional Basis: Article 41 of the Japanese Constitution declares the Diet to be the "sole law-making organ of the State." While Article 73, item 6 allows the Cabinet to enact Cabinet Orders to execute laws, it specifies that such orders cannot include penal provisions "unless authorized by such law." This principle is extended to other significant regulatory delegations; they must not be based on a "blanket delegation" (hakuchi inin) but rather on a specific authorization from a Diet-enacted law that outlines the purpose and criteria for the delegated rulemaking.

- "Clarity of Authorizing Intent": This judgment is particularly noteworthy for its emphasis on the "clarity of authorizing intent" (juken shushi no meikakusei). This suggests that when a ministry ordinance imposes significant restrictions, especially on constitutionally protected freedoms like occupational activities, the parent law must provide a clearly discernible basis for those specific restrictions. The Court's willingness to consider legislative process discussions in assessing this clarity is also a notable aspect. Some legal commentators have pointed out that this "clarity of authorizing intent" was a novel expression in Supreme Court jurisprudence at the time. While some view it as specific to the facts of this case rather than a new general principle, others see it as a potentially significant development for controlling delegated legislation, particularly by linking it to the protection of constitutional rights.

Whose Responsibility? Flawed Law or Flawed Regulation?

A significant aspect of this decision is that the Supreme Court chose to invalidate the MHLW Implementing Rules (the regulation) for exceeding the scope of delegation, rather than finding the New Pharmaceutical Affairs Act (the parent law) itself unconstitutional for making an overly vague or "blanket" delegation.

- Some legal analyses have suggested that the delegating provisions in the New Pharmaceutical Affairs Act could themselves have been challenged as being too open-ended and thus unconstitutional. Other interpretations suggest the Supreme Court might have been implicitly applying a "constitutionally conformable interpretation" to the parent Act to uphold its validity while striking down the specific rules made under it.

- The commentary provided with the source material suggests that the Supreme Court might be viewing "clarity of authorizing intent" as a kind of "activation requirement" for an agency's power to make administrative legislation. If this clarity is absent in the parent law regarding a specific, restrictive regulation, then the responsibility for overreach lies with the administrative agency that enacted the regulation. This approach allows courts to address problems of vague delegation by focusing on the legality of the resulting ordinance, rather than necessarily having to declare the parent statute unconstitutional.

Significance and Impact of the Ruling

The 2013 Supreme Court decision on online pharmaceutical sales carried substantial significance:

- Reinforcement of Judicial Review: It strongly reaffirmed the judiciary's power to review the substance of delegated legislation and to strike down administrative rules that overstep the boundaries set by the Diet, especially when those rules impact constitutional freedoms such as the freedom of occupational activity.

- Potential Stiffening of Clarity Requirements: The emphasis on "clarity of authorizing intent" may signal a move towards requiring greater precision in statutes that delegate significant regulatory powers to ministries and agencies.

- Impact on E-commerce and Pharmaceutical Regulation: The case was a major event in the ongoing debate in Japan regarding the online sale of pharmaceuticals. It balanced arguments about public safety and the need for professional pharmaceutical advice against consumer convenience and the commercial freedom of online vendors. While this judgment invalidated specific MHLW rules, the broader legislative and regulatory discussions about ensuring safety in online drug sales have continued.

- Addition to Precedents: This ruling joined a growing list of Supreme Court precedents where administrative regulations have been found void for exceeding their delegated authority.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2013 decision is a critical marker in Japanese administrative and constitutional law, particularly concerning the boundaries of executive rulemaking. The Court's focus on whether the legislature's intent to authorize specific, restrictive regulations was "clearly discernible" from the parent statute provides a key lesson for how laws delegating power might need to be drafted and how they will be interpreted by the courts, especially when fundamental rights and significant economic activities are at stake. This judgment champions the principle that administrative actions must remain subordinate to, and clearly authorized by, the legislative will expressed in Diet-enacted laws.