Japan Supreme Court Confirms Face‑to‑Face Pharmacist Guidance for “Drugs Requiring Guidance” (2021 Online‑Pharmacy Ruling)

TL;DR

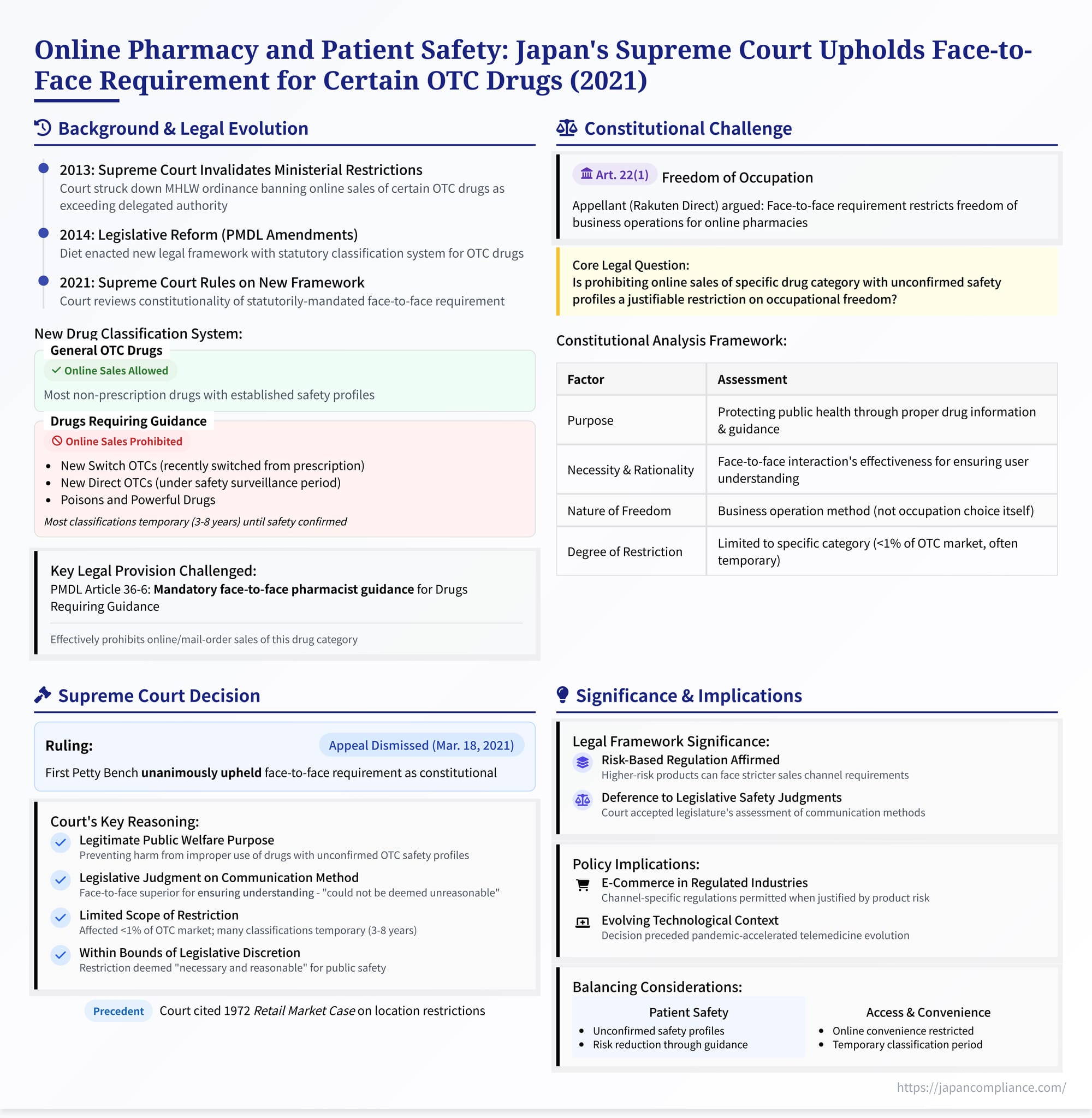

Japan’s 2021 Supreme Court ruling upheld the Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Act provision that “Drugs Requiring Guidance” must be sold only after face‑to‑face counselling by a pharmacist. The Court held that (i) protecting public health is a legitimate aim; (ii) in‑person interaction is a rational means to ensure patient understanding for higher‑risk OTC drugs; and (iii) the restriction is proportionate because it covers a tiny, temporary subset of the OTC market. Consequently, online retailers remain barred from selling these drugs until they are reclassified as general OTC medicines.

Table of Contents

- Background: Regulating Online Drug Sales After a Landmark Ruling

- The Constitutional Challenge by an Online Retailer

- The Supreme Court's Decision: Face‑to‑Face Rule Upheld

- Significance and Analysis

- Conclusion

The rise of e-commerce has revolutionized retail across sectors, including pharmaceuticals. However, the online sale of medicines presents unique challenges, requiring a balance between consumer convenience and access, business freedom for online retailers, and the paramount need to ensure patient safety through appropriate information and guidance. Japan has grappled with this balance, particularly concerning Over-The-Counter (OTC) drugs. A 2013 Supreme Court decision invalidated broad restrictions on online OTC sales imposed by ministerial ordinance, prompting legislative reforms. A subsequent 2021 Supreme Court ruling examined the constitutionality of the new legislative framework itself, specifically its requirement for face-to-face pharmacist interaction when selling a newly created category of "Drugs Requiring Guidance." This case, formally the Case Concerning Request for Confirmation of Right to Sell Drugs Requiring Guidance Online, etc. (Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, Reiwa 1 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 179, March 18, 2021), provides significant insights into how Japan's judiciary weighs occupational freedom against public health justifications for regulating specific sales channels based on perceived product risk.

Background: Regulating Online Drug Sales After a Landmark Ruling

Prior to 2013, regulations issued by Japan's Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) under the Pharmaceutical Affairs Act effectively banned the internet or mail-order sale of certain categories of non-prescription (OTC) drugs deemed higher risk (specifically, former "Category 1" and "Category 2" drugs), requiring them to be sold face-to-face by pharmacists or registered sellers. However, in January 2013, the Supreme Court ruled that these restrictions, being implemented solely through ministerial ordinance without clear authorization in the Act itself, were illegal and invalid as exceeding the scope of delegated legislative power.

This ruling necessitated legislative action. The Diet responded by amending the Pharmaceutical Affairs Act (later renamed the Act on Securing Quality, Efficacy and Safety of Products Including Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices, or PMDL) in late 2013, with the key changes taking effect in June 2014. This amendment created a new framework for OTC drug classification and sales channels:

- General OTC Drugs (一般用医薬品, ippan-yō iyaku-hin): This category encompasses most non-prescription drugs. The 2014 rules generally permitted the online and mail-order sale of these drugs, subject to certain rules regarding information provision depending on the drug's risk sub-classification (e.g., Class 1 OTC still required pharmacist involvement, though not necessarily face-to-face for all interactions).

- Drugs Requiring Guidance (要指導医薬品, yō-shidō iyaku-hin): The amendment created this new, distinct category (PMDL Art. 4(5)(3)). These are drugs still considered OTC (i.e., not requiring a prescription) but deemed to necessitate special attention and guidance from a pharmacist for safe use. This category includes:

- New Switch OTCs: Drugs recently switched from prescription-only status to OTC status. Specifically, those whose approval differs significantly from existing drugs and are still within a mandatory post-marketing safety surveillance period (generally 3 years) set by MHLW ordinance (Art. 4(5)(3)(i)).

- Identical Switch OTCs: Drugs approved as identical to a newly switched OTC drug, also within the initial safety surveillance period (Art. 4(5)(3)(ii)).

- New Direct OTCs: Drugs approved directly as OTC without prior prescription status, typically subject to a re-examination period (usually 4-8 years) to gather safety data (also falling under Art. 4(5)(3)(i) or (ii) via the ordinance defining the period).

- Poisons and Powerful Drugs: Drugs specifically designated as poisons (dokuyaku) or powerful drugs (gekiyaku) under the Act (Art. 4(5)(3)(iii) & (iv)).

The MHLW Minister designates specific drugs for this category based on the opinion of the Pharmaceutical Affairs and Food Sanitation Council, identifying them as needing face-to-face pharmacist interaction for proper use. Importantly, drugs in this category (other than poisons/powerful drugs) are intended to be temporary classifications. After the initial safety surveillance or re-examination period, they are typically re-evaluated, and if safety is confirmed, they are reclassified as General OTC drugs.

- Face-to-Face Sales Mandate for Drugs Requiring Guidance: The crucial element challenged in the 2021 case was embedded in Article 36-6 of the amended PMDL. This article mandates that pharmacies and licensed store retailers:

- Must have a pharmacist sell or supply Drugs Requiring Guidance (Art. 36-5(1)).

- Must ensure the pharmacist provides necessary information and guidance face-to-face (taimen) using written materials (Art. 36-6(1)).

- Must ensure the pharmacist confirms necessary user information (age, other medications, etc.) beforehand (Art. 36-6(2)).

- Must not sell or supply the drug if face-to-face information provision or guidance cannot be performed, or if proper use cannot otherwise be ensured (Art. 36-6(3)).

This set of provisions (referred to in the judgment as 本件各規定, honken kaku kitei) effectively banned the internet or mail-order sale of any drug classified as a Drug Requiring Guidance, as face-to-face interaction is impossible through these channels.

The Constitutional Challenge by an Online Retailer

The appellant, R (Rakuten Direct, Inc., which had merged with the original plaintiff, Kenko.com), was a licensed store-based retailer that also operated a significant online business selling pharmaceuticals, including OTC drugs, via the internet. R had been engaged in online drug sales even before the 2014 legislative changes.

The 2014 rules, while opening the door for online sales of most General OTC drugs, created a barrier for the newly defined category of Drugs Requiring Guidance. R argued that the legal provisions mandating face-to-face pharmacist sales (Article 36-6(1) & (3)), thereby prohibiting online sales for this category, were unconstitutional.

R filed suit against the State (represented by the MHLW Minister), primarily arguing that these provisions violated Constitution Article 22, Paragraph 1, which guarantees the freedom "to choose [one's] occupation to the extent that it does not interfere with the public welfare." This freedom is understood to encompass not only the choice of occupation but also the freedom of business activity. R sought, among other things, a judicial confirmation of its right or legal status to sell certain drugs designated as Drugs Requiring Guidance via online/mail-order methods.

Both the Tokyo District Court (in 2017) and the Tokyo High Court (in 2019) ruled against R, finding the face-to-face requirement for Drugs Requiring Guidance to be a constitutional regulation under Article 22(1). R appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Face-to-Face Rule Upheld

The First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court unanimously dismissed R's appeal, affirming the lower courts' decisions and upholding the constitutionality of the face-to-face sales requirement for Drugs Requiring Guidance.

The Court applied the established framework for reviewing restrictions on occupational freedom, derived from the landmark 1975 Pharmacy Case (which dealt with restrictions on pharmacy locations).

1. The Constitutional Framework (Article 22(1)):

- The Court reaffirmed that Article 22(1) protects both the freedom to choose an occupation and the freedom of occupational activity (business operations).

- Restrictions on this freedom take various forms, and their constitutionality cannot be judged uniformly. A careful balancing analysis is required.

- This analysis involves examining and weighing:

- The purpose of the regulation (must serve the public welfare).

- The necessity and rationality of the specific regulatory measure chosen to achieve that purpose.

- The nature and content of the occupational freedom being restricted.

- The extent or degree of the restriction imposed.

- Crucially, the Court emphasized that this balancing is primarily the responsibility of the legislature. Courts should respect the Diet's policy judgment as long as the purpose is legitimate and the chosen means fall within the bounds of reasonable legislative discretion (gōri-teki sairyō no han'i), acknowledging that the scope of this discretion can vary depending on the nature of the matter.

2. Applying the Framework to the Face-to-Face Requirement:

The Court then applied this balancing test to the specific requirement for face-to-face pharmacist interaction for Drugs Requiring Guidance.

- Purpose of the Regulation: The Court identified the purpose as protecting public health and safety by preventing harm resulting from the improper use of this specific category of drugs. This involves ensuring appropriate information and guidance are provided by a pharmacist. The Court found this purpose to be clearly consistent with the public welfare, as mandated by the PMDL's overarching goal (Article 1).

- Necessity and Rationality of the Means (Face-to-Face Interaction):

- Nature of the Drugs: The Court stressed the unique status of Drugs Requiring Guidance. They are intended for consumer self-selection (unlike prescription drugs) but possess unconfirmed safety profiles in the OTC context (being new Switch/Direct OTCs under review) or inherent risks (poisons/powerful drugs).

- Need for Effective Guidance and Understanding: Given this profile, the Court found "considerable rationality" (sōtō no gōrisei) in requiring pharmacists, before selling these drugs, to gather maximum user information (via pre-sale checks on age, medication history, etc.) and provide appropriate guidance, crucially ensuring the user's understanding (rikai o kakujitsu ni kakunin suru) to guarantee proper use.

- Legislature's Assessment of Communication Methods: The Court addressed the core of the dispute: the mandate for face-to-face interaction. It interpreted the legislative choice as being based on the assessment that face-to-face communication is superior to non-face-to-face methods (like phone or internet/email) specifically for the purpose of ensuring the user's understanding. The reasoning implied is that face-to-face interaction allows for observing reactions, adapting explanations based on immediate feedback, and confirming comprehension through direct dialogue in a way that remote text or voice communication cannot reliably replicate. The Court held that this legislative assessment, prioritizing safety through guaranteed understanding for this specific risk category, could not be deemed unreasonable (fugōri de aru to iu koto wa dekinai).

- Nature and Extent of the Restriction: The Court then evaluated the impact of this regulation on occupational freedom.

- Not a Ban on Occupation Choice: The rule does not prevent individuals from becoming pharmacists or operating pharmacies/stores. It restricts only the method of selling a specific category of products.

- Limited Scope of Affected Products: The face-to-face requirement applies only to Drugs Requiring Guidance. The Court noted factual findings that this category constituted a very small fraction (less than 1%) of the overall OTC drug market in terms of sales volume. Furthermore, for most drugs in this category (Switch/Direct OTCs), the designation is temporary, lasting only for the duration of the post-marketing surveillance or re-examination period (typically 3-8 years), after which they can transition to the General OTC category (permitting online sales).

- Conclusion on Degree of Restriction: Considering the small market share and the temporary nature of the classification for many products, the Court concluded that the restriction imposed by the face-to-face requirement did not constitute a major limitation (seigen no teido ga ōkii to iu koto mo dekinai) on occupational activity.

- Balancing Conclusion and Deference: Weighing all these factors – the legitimate public health purpose, the perceived necessity and rationality of requiring face-to-face interaction to ensure understanding for this specific risk category, and the limited nature and extent of the resulting restriction on business activities – the Court concluded that the legislative judgment embodied in the provisions did not exceed the bounds of reasonable discretion.

- Finding on Constitutionality: Therefore, the provisions (Article 36-6(1) & (3)) requiring face-to-face pharmacist interaction for Drugs Requiring Guidance do not violate Constitution Article 22(1). The Court cited the 1972 Retail Market Case (upholding restrictions on retail market locations based on rational planning) as relevant precedent supporting the constitutionality of necessary and reasonable regulations on business activities for the public welfare.

Significance and Analysis

The 2021 Supreme Court decision provides important clarity on the regulation of online pharmaceutical sales in Japan, particularly in the wake of legislative reforms following the 2013 ruling.

- Upholding Risk-Based Regulation of Sales Channels: The ruling strongly affirms the legislature's authority to differentiate regulatory requirements for different categories of drugs based on their perceived risk profiles. It validates the principle that higher-risk or less-established OTC drugs (like those newly switched or directly approved, or poisons/powerful drugs) can be subjected to stricter sales channel regulations (like mandatory face-to-face interaction) compared to lower-risk, well-established OTC drugs, even if this limits online commerce for the higher-risk category.

- Deference to Legislative Judgment on Safety Measures: The Court showed significant deference to the Diet's assessment regarding the relative effectiveness of different communication methods (face-to-face vs. remote) for achieving the specific safety goal of ensuring patient understanding for Drugs Requiring Guidance. While the 2013 ruling was skeptical of justifications for broad online sales bans under mere ordinance, this 2021 ruling accepted the legislature's judgment, embedded in statute, that face-to-face interaction provides a safety advantage for this particular category that justifies restricting other channels.

- Limited Scope as a Key Factor: The Court's emphasis on the small market share and temporary nature of the Drug Requiring Guidance category was crucial to its proportionality analysis. This suggests that regulations imposing similar channel restrictions on broader categories of products or on a permanent basis might face stricter scrutiny under Article 22(1). The limited impact on overall business freedom was a key factor in upholding the regulation.

- Implications for E-commerce in Regulated Industries: The decision has broader implications for e-commerce in sectors involving public health and safety. It confirms that governments can impose channel-specific regulations based on product risk assessments, potentially limiting purely online business models for certain goods or services where face-to-face interaction is deemed necessary for safety or consumer protection.

- Evolving Technological Context: The ruling was based on the legal and technological landscape preceding the major global shift towards telemedicine and remote consultations accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Since this decision, further legislative changes in Japan have enabled online medication guidance by pharmacists for prescription drugs under specific conditions. This raises questions about the long-term validity of the Court's premise regarding the inherent inferiority of remote communication for ensuring patient understanding, at least from a technological feasibility standpoint. As remote communication technologies and practices continue to evolve, the specific factual assessment underlying the Court's 2021 rationality finding for requiring face-to-face interaction might be revisited in future legislative debates or legal challenges.

Conclusion

The 2021 Supreme Court decision upheld the constitutionality of Japan's legal requirement for face-to-face pharmacist interaction when selling "Drugs Requiring Guidance," effectively prohibiting the online sale of this specific category of non-prescription medicines. The Court found the regulation to be a permissible restriction on occupational freedom under Article 22(1), justified by the public welfare purpose of ensuring patient safety for drugs with relatively unconfirmed OTC safety profiles or higher inherent risks. Key factors in the Court's decision were its deference to the legislature's assessment of the necessity of face-to-face communication for ensuring user understanding of these particular drugs, and the limited scope and temporary nature of the restriction. While settling the constitutional question based on the law and circumstances at the time, the ruling exists within a rapidly evolving landscape of online healthcare delivery, suggesting that the regulatory balance between access, safety, and business freedom in the pharmaceutical e-commerce space will likely remain a dynamic area.

- When a Lie Becomes a Crime: Japan's Landmark Case on Lying for an Arrested Friend

- The Scapegoat Gambit: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Aiding an Arrested Criminal's Escape

- Memory vs. Truth: How Japan's High Court Defined Perjury Over a Century Ago

- 要指導医薬品について(厚生労働省資料, PDF):contentReference[oaicite:0]{index=0}

- 医薬品の販売制度に関する検討会 とりまとめ(厚生労働省資料, PDF):contentReference[oaicite:1]{index=1}