One Document, Two Testators? Japan's Supreme Court on the Prohibition of Joint Wills

Date of Judgment: September 11, 1981 (Showa 56)

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Case No. Showa 54 (o) No. 1208 (Claim for Confirmation of Will Invalidity)

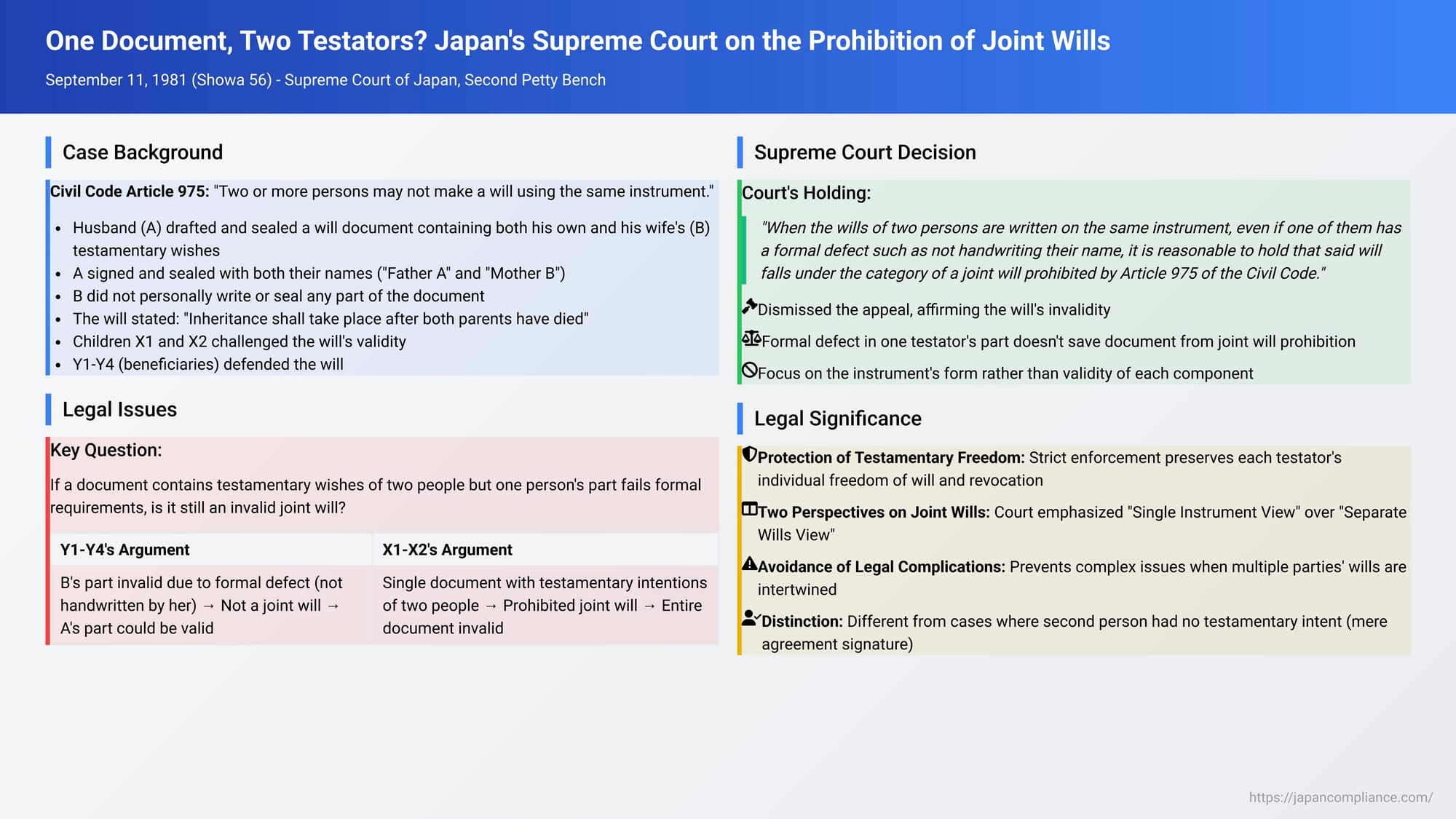

Japanese law, under Article 975 of the Civil Code, prohibits "joint wills" – that is, a will made by two or more persons using the same instrument (document). The primary purpose of this prohibition is to safeguard the individual freedom of each testator to make and revoke their will without influence or constraint from another party, and to prevent complex legal issues regarding the will's validity and effect. A critical question arose before the Supreme Court of Japan in 1981: what happens if a single document appears to contain the testamentary dispositions of two individuals, but one of those individuals did not actually execute their purported part of the will according to the strict formalities required for a holographic (handwritten) will? Is the entire document still considered an invalid joint will?

Facts of the Case: A Will Document with Two Names, One Author

The case involved the estate of a married couple, A (husband) and B (wife), and a holographic will document left behind.

- The Deceased Couple: A passed away on July 10, 1968, and his wife B passed away later, on July 8, 1976.

- The Heirs: The couple had nine children, including X1 and X2 (the plaintiffs/appellees, who did not benefit significantly under the terms of the disputed will) and Y1 through Y4 (the defendants/appellants, who were designated as primary beneficiaries).

- The Disputed Will Document: A holographic will document (the "Will Document") was discovered.

- Creation of the Document: It was established as a fact that the entire Will Document was written and sealed solely by the husband, A. This included not only the portions detailing his own testamentary wishes but also the sections purporting to express B's testamentary intent, as well as the signatures and seals for both "Father A" and "Mother B." B, the wife, did not personally handwrite or affix her seal to any part of this document.

- Content of the Document: The Will Document contained several provisions. It detailed the distribution of specific properties to Y1-Y4 and other beneficiaries. Crucially, it also included a clause stating: "However, the inheritance of the above five properties (real estate) shall take place after both parents have died. When A (father) dies, B (mother) shall first inherit all property." This clause clearly indicated testamentary intentions attributed to both A and B concerning the sequence of inheritance (A's property to B first) and the ultimate distribution of assets after both had passed.

- The Legal Challenge by X1 and X2: X1 and X2, children of A and B who did not stand to benefit significantly from the Will Document, filed a lawsuit against Y1-Y4. They sought a judicial declaration that the Will Document was invalid. Their central argument was that the document, by appearing to contain the testamentary dispositions of two individuals (A and B) on a single instrument and bearing what purported to be the names and seals of both (even though all executed by A), violated the prohibition against joint wills found in Article 975 of the Civil Code.

- Lower Court Rulings Declaring the Will Invalid:

- First Instance Court (Osaka District Court): This court ruled in favor of X1 and X2, declaring the will invalid. It found that the Will Document, both in its physical form (bearing the names and seals attributed to both "Father A" and "Mother B") and in its substantive content (containing expressions of testamentary intent clearly linked to both A and B), constituted a joint will prohibited by law.

- High Court (Osaka High Court): The High Court affirmed the first instance court's decision, also concluding that the Will Document was an invalid joint will.

- Appeal by Y1-Y4 to the Supreme Court: Y1-Y4, the beneficiaries under the will, appealed to the Supreme Court. One of their key arguments was that if B's purported portion of the will was not actually written or sealed by B herself, but was entirely created by A, then B's "will" failed to meet the strict formal requirements for a valid holographic will (as per Article 968, Paragraph 1, which mandates that the testator personally handwrite the entire text, date, and name, and affix their seal). They implied that if B's part was independently invalid due to these formal defects, then the document as a whole might not constitute a "joint will" of two valid testamentary acts, and A's portion, if formally compliant and separable, might be upheld.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Formal Defect in One Part Does Not Save a Joint Will

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by Y1-Y4, thereby affirming the invalidity of the entire Will Document.

The Court's core holding was concise and direct:

"When the wills of two persons are written on the same instrument, even if one of them has a formal defect such as not handwriting their name, it is reasonable to hold that said will (the entire document) falls under the category of a joint will prohibited by Article 975 of the Civil Code."

In essence, the Supreme Court determined that the fact that a single document purports to contain the testamentary dispositions of two individuals is sufficient to trigger the prohibition against joint wills. The formal validity or invalidity of one of those individual's purported testamentary acts, when viewed in isolation, does not prevent the document as a whole from being classified as a prohibited joint will. If the instrument itself indicates it's intended to embody the wills of two (or more) people, it falls foul of Article 975.

Legal Principles and Significance

This 1981 Supreme Court decision is a key ruling on the interpretation of Article 975 and the strict prohibition of joint wills in Japan.

- Purpose of Prohibiting Joint Wills (Article 975): The PDF commentary accompanying this case explains the fundamental reasons behind this prohibition:

- Protection of Testamentary Freedom: To ensure that each testator's will is an expression of their own free and unconstrained individual intent, without being unduly influenced or fettered by the wishes or intentions of another person involved in a joint testamentary act.

- Preservation of Freedom of Revocation: A will is generally revocable by the testator at any time before their death. Joint wills complicate this, as the death of one testator might make it difficult or legally uncertain for the survivor to revoke or alter their own part of the joint will.

- Avoidance of Legal Complications: If one part of a joint will is found to be invalid for some reason (e.g., formal defect, lack of capacity, undue influence), it can create complex legal issues regarding the validity and effect of the other part(s) of the will. Similarly, issues can arise if the testators die at different times.

- Limited Practical Necessity: The objectives often sought through a joint will (e.g., reciprocal bequests between spouses, common plan for ultimate beneficiaries) can generally be achieved through separate, individual wills that may be coordinated if desired. Given the potential downsides, the law sees little compelling need to permit joint wills.

The overarching goal is to protect the testator's individual autonomy in making what is often their final and most significant legal act regarding their property.

- Defining a "Joint Will" – The Supreme Court's Strict Approach:

The PDF commentary discusses two potential analytical "perspectives" (視角 - shikaku) when assessing a document that contains testamentary wishes of multiple individuals (say, A and B):- Perspective 1 (Separate Wills View): This approach would first examine if there are, in substance, two distinct wills (A's will and B's will) on the same paper. It would then assess the formal validity of each will independently. If, for example, B's purported will is found to be formally defective (e.g., not handwritten by B, as in this case), then B's will is invalid. The analysis would then focus on whether A's will, if formally valid and meaningfully separable from B's invalid part, could be upheld.

- Perspective 2 (Integrated Will / Single Instrument View): This approach focuses more on the form of the document itself. If a single instrument purports to embody the testamentary acts of two or more people, it is treated as one prohibited "joint will," regardless of whether each individual component would have been valid if executed separately.

The Supreme Court's 1981 decision, by invalidating the entire Will Document even though B's purported will was not actually executed by her according to the formalities of a holographic will, clearly aligns with Perspective 2 or at least reflects a very strict interpretation of Article 975's prohibition on "two or more persons" making "a will" "by the same instrument." The very act of creating a single document intended to serve as the will for multiple individuals appears to be the trigger for the prohibition. The PDF commentary suggests that the judgment views the issue from the standpoint of whether there's an "A & B will" (an integrated act documented on one instrument) rather than trying to dissect it into a separate A-will and B-will for validity assessment. []

- Content Interrelatedness vs. Formal Prohibition: Legal scholarship, as noted in the commentary, often categorizes joint wills based on the interrelatedness of their content (e.g., "simple joint wills" with independent dispositions, "reciprocal joint wills" where A leaves property to B and B leaves property to A, or "correlative joint wills" where A's dispositions are conditional on B's). Some scholars have argued that if the contents are truly independent and physically separable on the document, the prohibition in Article 975 might not apply so strictly, or that valid parts might be salvaged. However, this Supreme Court decision, dealing with a will whose contents were clearly interrelated (particularly the clause about B inheriting from A first, and then the property passing to others after both die), applied the prohibition broadly without delving into such nuanced distinctions of content separability. Its direct language suggests that the formal aspect of using a single instrument for the wills of multiple people is paramount.

- Comparison with Cases Lacking Testamentary Intent from One Party: The PDF commentary distinguishes this case from situations where a document might bear two names, but only one person actually had testamentary intent. It references a Tokyo High Court decision (Showa 57.8.27) where a will document was signed by a husband (A) and also had his wife's (Y) name on it. However, it was found that Y had no independent testamentary intent; A had merely added her name to signify her agreement with his will. In such a case, because there was no "will" by Y in the first place, the document was not deemed a prohibited joint will. The present Supreme Court case is different because the Will Document did contain clear statements of testamentary intent attributed to both A and B.

- Scholarly Critique and Defense of the Judgment:

- Critique (Favoring Perspective 1): Some legal scholars, as highlighted in the commentary, have criticized this judgment's outcome. They argue from "Perspective 1," suggesting that B's purported will was independently invalid due to its failure to meet the formal requirements for a holographic will (it was not handwritten or sealed by B). Therefore, the analysis should have focused solely on A's portion of the will. If A's dispositions were formally compliant and separable from B's invalid portion, A's will might have been upheld. This approach aims to salvage the testator's (A's) ascertainable intent as much as possible.

- Defense (Supporting Perspective 2, Aligned with the Judgment): The PDF commentary also provides a rationale supporting the Supreme Court's stricter approach. If B's part is deemed invalid, attempting to determine A's hypothetical intent regarding the continued validity of A's own part in isolation becomes highly speculative and difficult, especially once both testators are deceased. The very purpose of the joint will prohibition is arguably to preemptively avoid such complex and uncertain inquiries into intertwined or dependent intentions. By invalidating the entire document when it purports to be the will of multiple persons, the law ensures clarity and avoids these interpretive quagmires. []

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1981 decision serves as a strong affirmation of the strict prohibition against joint wills in Japanese law under Article 975 of the Civil Code. It clarifies that if a single document contains what appear to be the testamentary dispositions of two or more individuals, it will be considered an invalid joint will, even if one of those individual's purported testamentary acts would be formally defective if viewed in isolation (e.g., lacking proper signature or seal by that person). This ruling prioritizes the formal integrity of the will-making process and the legislative intent to protect each testator's freedom of will and revocation, and to avoid the legal complexities inherent in joint testamentary instruments. It underscores that individuals wishing to make wills, even if they have coordinated plans, must do so through separate, individual documents to ensure their validity.