One Bullet, Two Victims: How Japanese Law Handles the "Error of the Object"

Decision Date: July 28, 1978

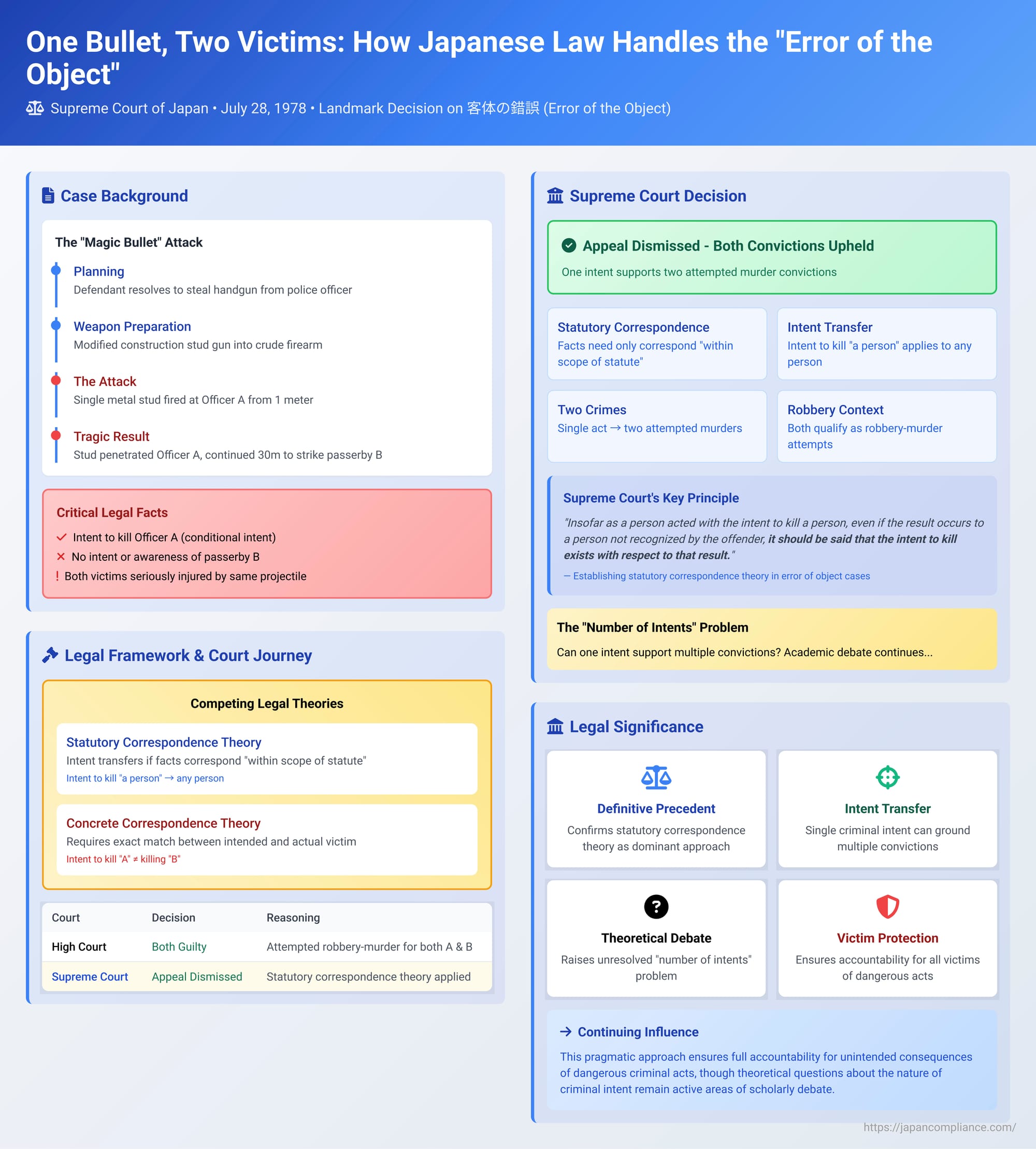

In the study of criminal law, a classic hypothetical tests the very nature of intent: an assailant shoots at person A but, having bad aim, misses and hits an innocent bystander, B. Is the assailant guilty of attempting to murder A and negligently injuring B? Or does the intent to kill "transfer" from A to B, making the assailant guilty of attempting to murder B? This is the legal puzzle known as "error of the object" or aberratio ictus.

On July 28, 1978, the Supreme Court of Japan was confronted with a real-life version of this problem that was even more complex. A single projectile, fired with the intent to harm one person, struck both the intended target and an unintended victim. The Court's decision in this case stands as a landmark ruling, powerfully affirming Japan's long-standing adherence to the "statutory correspondence theory" (hōteiteki fugōsetsu) and clarifying how a single criminal intent can result in multiple criminal convictions.

The Factual Background: The Attack on the Officer

The defendant had resolved to steal a handgun from a uniformed police officer, A. To carry out his plan, he armed himself with a crude, homemade firearm, which he had fashioned by modifying a construction stud gun to fire a metal stud.

On a sidewalk in Tokyo, the defendant stalked Officer A. Approaching him from behind to a distance of about one meter, he aimed the stud gun at A's right shoulder area and fired.

The metal stud performed like a macabre "magic bullet." It struck Officer A, inflicting a serious, penetrating wound to his chest. The stud then passed completely through the officer's body and continued its trajectory, striking an innocent passerby, B, who happened to be about 30 meters ahead. B was also seriously injured with a penetrating abdominal wound.

The defendant was subsequently charged with, among other crimes, attempted robbery-murder for the injuries caused to both Officer A and the bystander B.

The Legal Dilemma: Intent Towards the Unintended Victim

The case presented the courts with a profound legal dilemma. The High Court, which first heard the appeal, found the defendant guilty of attempted robbery-murder for his actions against both A and B. In its factual findings, it determined that the defendant possessed at least a conditional intent (mihitsu no kōi) to kill Officer A. However, the court explicitly found that the defendant had no intent to kill the unknown bystander, B. He was completely unaware of B's existence.

The defendant's lawyer seized on this apparent contradiction. In his appeal to the Supreme Court, he argued that since the court itself found that the defendant had no intent to kill B, it was a logical and legal impossibility to convict him of the intentional crime of attempted robbery-murder with respect to B. The conviction, he argued, was a violation of legal precedent.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: The Power of Statutory Correspondence

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal and upheld both convictions for attempted robbery-murder. In its reasoning, the Court provided a clear explanation of how the statutory correspondence theory resolves this exact problem.

The Core Legal Principle:

The Court began by stating the general rule for criminal intent: it requires a recognition of the facts that constitute the crime. However, it immediately qualified this with the core tenet of the statutory correspondence theory:

"[I]t is not necessary for the facts recognized by the offender and the facts that actually occurred to correspond concretely. It is sufficient that both facts correspond within the scope of the statute."

Applying the Principle to Error of the Object:

The Court then applied this abstract principle to the specific scenario of a missed or stray shot:

"[I]nsofar as a person acted with the intent to kill a person, even if the result occurs to a person not recognized by the offender, it should be said that the intent to kill exists with respect to that result."

In this view, the law is not concerned with the specific identity of the victim. The legally relevant fact is the intent to kill "a person" and the result of a life-threatening injury to "a person." Because the intended victim and the actual victim are both "persons," the facts correspond within the scope of the murder statute.

The Conclusion on Two Crimes from One Act:

Applying this logic, the Supreme Court found that the defendant's single act of firing the stud gun resulted in two distinct attempted murder convictions:

- Attempted Murder of A: This was straightforward, as A was the intended victim.

- Attempted Murder of B: This was also established because the defendant's intent to kill "a person" (A) was legally transferred to the unintended victim, B.

Finally, since both of these attempted murders were committed as the means to carry out the robbery of Officer A's handgun, the Court concluded that both crimes constituted attempted robbery-murder.

A Deeper Dive: Statutory Correspondence and the "Number of Intents"

This 1978 decision is a powerful affirmation of the statutory correspondence theory, which has long been the dominant view in Japanese courts, in contrast to the minority "concrete correspondence theory" that would require a match between the specific intended victim and the actual victim.

However, the ruling raises a deeper and more controversial theoretical question known as the "number of intents" problem (kōi no kosū). How can a single intent—the intent to kill one person, A—be used to ground two separate convictions for attempted murder, one for A and one for B?

The prevailing judicial view in Japan, often called the "multiple intentional crimes theory" (sū-koihan-setsu), holds that this is legally sound. This theory posits that when an actor unleashes a deadly force with a criminal intent, they are morally and legally responsible for all the harm that directly results, even if it exceeds their specific expectation. The blameworthiness lies in the decision to commit the dangerous act itself, and that single blameworthiness can ground multiple convictions for the resulting harms.

This approach, while pragmatic, has been subject to various academic critiques:

- Conflict with Other Legal Principles: Some scholars argue that allowing one intent to "do double duty" clashes with the spirit of other legal provisions, such as Article 38(2) of the Penal Code, which prevents a person who intended a minor crime from being convicted of a more serious one if an unexpectedly grave result occurs. The principle seems to be that liability should not extend beyond what the actor foresaw.

- The Nature of a Crime as a Violation of an Interest: A more sophisticated critique focuses on the nature of the crime itself. The crime of "murder of A" and the crime of "murder of B" are legally distinct because they represent the violation of two separate and distinct legal interests: the life of A and the life of B. If the crimes are distinct because the violated interests are distinct, then logically, each should require its own corresponding intent. The intent to violate A's right to life is not the same as the intent to violate B's. The statutory correspondence theory, by treating all "persons" as legally interchangeable, effectively papers over this crucial distinction.

Conclusion: A Pragmatic but Controversial Doctrine

The 1978 Supreme Court decision is a clear and powerful application of the statutory correspondence theory to a complex "error of the object" scenario. It firmly establishes that in Japanese law, when an assailant acts with the intent to kill one person, their criminal intent can be "transferred" to any unintended victims who are also harmed by the same act. This allows for separate convictions for each victim, ensuring the perpetrator is held fully accountable for all the harm they unleashed.

While this approach has the benefit of being a practical tool for achieving what many would consider a just result, it remains theoretically controversial. The unresolved "number of intents" problem and the debate over the fundamental nature of criminal intent highlight the deep philosophical questions that arise when a single, violent act has unforeseen and tragic consequences, forcing the legal system to choose between a concrete accounting of the defendant's mind and a broader accounting of the harm they have caused.