One Act, Two Crimes: Japan's Supreme Court on Aiding and Abetting a Criminal Spree

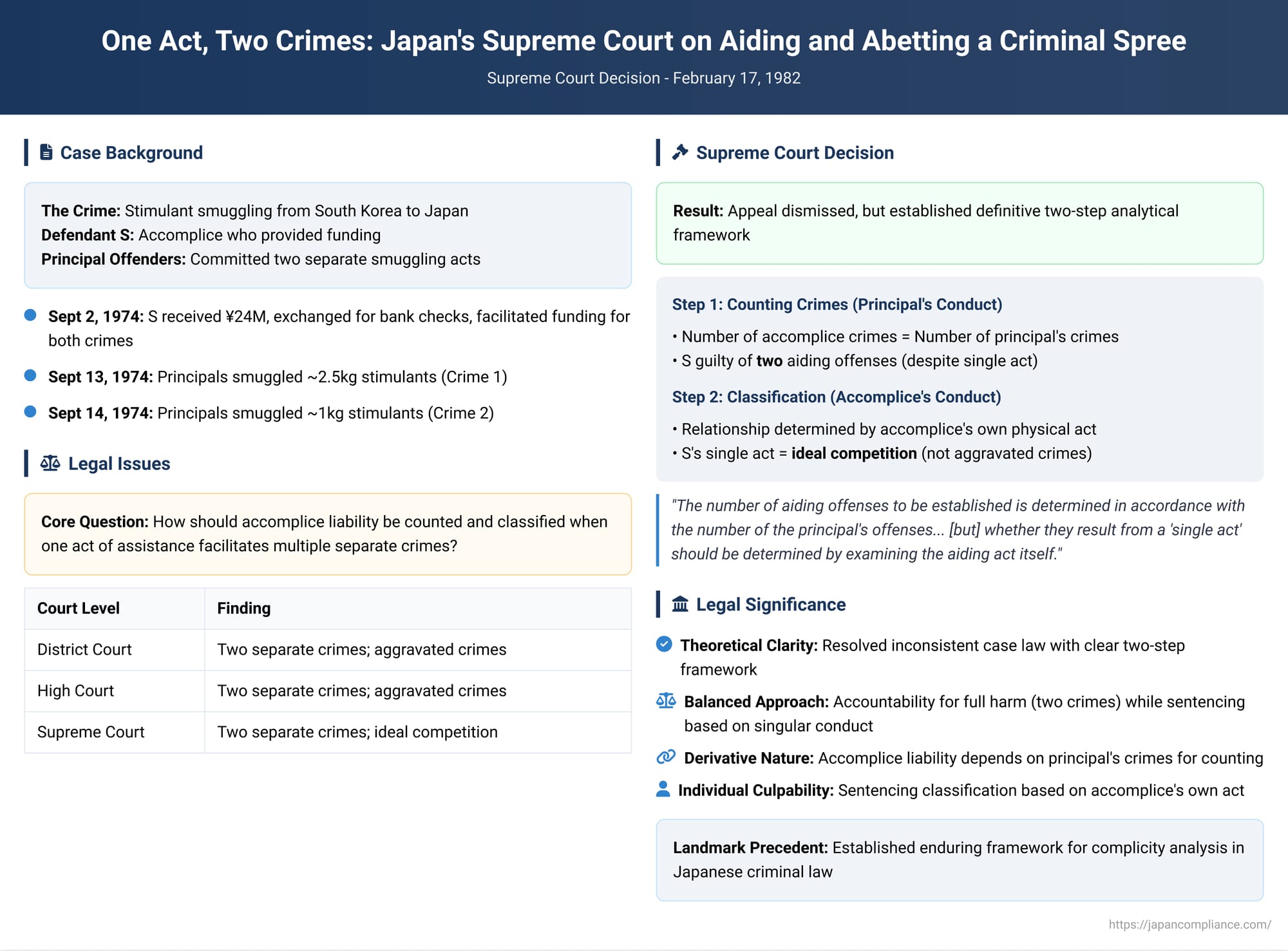

On February 17, 1982, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark decision that resolved a long-standing puzzle in the law of complicity. The case, involving violations of the Stimulant Control Act, addressed a critical question: If an accomplice performs a single act of assistance that enables principal offenders to commit multiple, separate crimes, how should the accomplice be charged and sentenced? The Court's elegant answer introduced a nuanced two-step analytical framework that distinguishes between counting the number of offenses and classifying their relationship for sentencing. This judgment brought crucial clarity to the derivative yet distinct nature of accomplice liability in Japanese criminal law.

The Factual Background: A Single Act of Funding, A Double Smuggling Operation

The case involved a conspiracy to smuggle stimulants from South Korea into Japan for profit. The principal offenders carried out two distinct criminal acts:

- On or around September 13, 1974, they acquired approximately 2.5 kilograms of stimulant powder in South Korea, which they then successfully smuggled into Japan by air.

- A day later, on or around September 14, 1974, they repeated the process, this time smuggling approximately 1 kilogram of stimulant powder into Japan.

These two smuggling operations were treated as two separate crimes committed by the principal offenders.

The defendant in this case, S, was an accomplice who aided and abetted these crimes. His involvement consisted of a single, unified act of assistance. On September 2, 1974, with full knowledge that the money was intended for purchasing the illegal stimulants, he received 24 million yen in cash from one of the principals. He then took this cash to a bank, combined it with one million yen from his own account, and exchanged the total amount for five bank-guaranteed checks. He delivered these checks to the principal, thereby facilitating the funding for both subsequent smuggling operations.

The legal dilemma was clear: S performed only one act of assistance, but this act facilitated two separate crimes. Was he guilty of one crime of aiding and abetting, or two? And if two, were they to be treated as separate "aggravated crimes" or as a "single act" resulting in "ideal competition"?

The Journey Through the Courts

The Osaka District Court, as the court of first instance, ruled that S was guilty of two separate offenses of aiding and abetting. It further held that these two offenses were in a relationship of aggravated crimes (heigo-zai), meaning they were to be treated as distinct criminal acts for sentencing purposes.

The defendant appealed, but the Osaka High Court upheld the lower court's decision. The High Court reasoned that accomplice liability is inherently dependent on the principal's crime. Therefore, the number of crimes committed by the accomplice should follow the number of crimes committed by the principal. Since the principals committed two crimes, the aider was also guilty of two crimes, and it was irrelevant that his act of assistance was singular or that he was unaware of the specific details of how the smuggling would be divided. This led the High Court to affirm that the two aiding offenses were aggravated crimes. The defendant then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Two-Step Framework

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal on procedural grounds but used its authority to issue a definitive ruling on the core legal question. The Court masterfully untangled the issue by establishing a clear, two-step framework for analyzing the plurality of crimes for accomplices.

Step 1: Counting the Number of Crimes (The Principle of Dependency)

First, to determine how many crimes of aiding and abetting have been committed, the court must look to the principal offender's conduct.

- The Rule: The number of aiding offenses is determined by, and is dependent on, the number of crimes successfully committed by the principal.

- The Court's Reasoning: "The crime of aiding and abetting is established by aiding the commission of a principal offense. Therefore, it is appropriate to conclude that the number of aiding offenses to be established is determined in accordance with the number of the principal's offenses."

- Application to the Case: Since the principal offenders committed two distinct acts of smuggling, thereby committing two separate crimes under the Stimulant Control Act, the defendant S was guilty of two corresponding crimes of aiding and abetting. This was true even though his act of assistance was a single event. On this point, the Supreme Court agreed with the lower courts' conclusion.

Step 2: Classifying the Relationship of the Crimes (The Accomplice's Own Act)

Second, once the number of crimes has been established, the next step is to determine their relationship for sentencing—whether they constitute aggravated crimes or are in ideal competition. For this determination, the court must look to the accomplice's own conduct.

- The Rule: Whether multiple aiding offenses result from a "single act" under Article 54 of the Penal Code must be judged by analyzing the physical act of the accomplice themselves.

- The Court's Reasoning: "When multiple aiding offenses as described above are established, the question of whether they result from a 'single act' as stated in Article 54, Paragraph 1 of the Penal Code should be determined by examining the aiding act itself, as it is appropriate to understand the 'act' in a crime of aiding and abetting to be none other than the aiding act performed by the aider."

- Application to the Case: The defendant S's conduct—receiving cash and exchanging it for bank-guaranteed checks—was a single, unified act. Therefore, even though this single act gave rise to two separate aiding offenses (as determined in Step 1), these two offenses were the result of a single act by the defendant. The Court concluded that the two crimes were in a relationship of ideal competition (kannenteki kyogo), not aggravated crimes.

The Final Verdict: A Legal Error Without Gross Injustice

The Supreme Court concluded that the High Court had erred in its judgment. While it was correct to find the defendant guilty of two aiding offenses, it was incorrect to classify them as aggravated crimes; they should have been deemed to be in ideal competition.

However, consistent with other rulings from this era, the Court did not overturn the original verdict. It held that this legal error was not so severe as to constitute a "gross injustice" that would mandate a reversal under the Code of Criminal Procedure. Thus, the appeal was dismissed, but the correct legal interpretation was now firmly established as precedent.

Significance and Theoretical Underpinnings

This 1982 decision is celebrated for bringing clarity and theoretical consistency to a muddled area of law.

- Resolving Inconsistency: Prior case law had been inconsistent, with the dominant view holding that both the number and relationship of an accomplice's crimes should slavishly follow the principal's crimes. This new two-step analysis provided a clear and predictable framework that separated the two issues.

- Theoretical Grounding: The framework is theoretically sound. The dependency in Step 1 reflects the derivative nature of accomplice liability; an accomplice's crime cannot exist without the principal's crime. The accomplice-centric focus in Step 2 aligns with the broader principle established in other Supreme Court cases that the "singularity" of an act for the purpose of sentencing should be based on a "naturalistic and social observation" of the defendant's own physical conduct.

- Balancing Principles: The ruling strikes a careful balance. It holds the accomplice accountable for the full scope of the harm they facilitated (two crimes), while sentencing them based on the singular nature of their own wrongful conduct (one act).

Remaining Questions

While the ruling provided a clear framework, legal scholars have noted it leaves some questions open. For instance, the commentary suggests the logic should extend to the crime of instigation (kyōsa) but may apply differently to joint principals (kyōdō seihan), who are held to a standard of "partial act, total responsibility". Furthermore, there is the complex issue of intent—what if the aider believed they were funding only one crime, but the money was used for two? While older case law suggests this wouldn't matter, modern theories of criminal intent could lead to different conclusions.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1982 decision on aiding and abetting remains a landmark of Japanese criminal jurisprudence. By creating a distinct, two-step analysis—counting the crimes based on the principal, but classifying their relationship based on the accomplice—the Court elegantly resolved the inherent tension between the derivative nature of complicity and the fundamental principle that an individual's punishment should reflect their own actions. It affirmed that while an accomplice's liability is born from the crime of another, their culpability for sentencing purposes is ultimately measured by the singularity of their own contribution to that crime.