On the Brink of Disaster: A Japanese Ruling on Endangering a High-Speed Railway

Japan's railway system is a global symbol of precision, safety, and reliability. What, then, does it take to legally "endanger" such a meticulously managed network? If a disgruntled landowner begins digging a massive trench right alongside a main line, creating a patently unstable cliff, at what point does their action cross the threshold from a private dispute into a major public safety crime? And how should a court weigh the conflicting opinions of on-site professionals who fear an imminent catastrophe against forensic engineers who later claim there was no real physical risk?

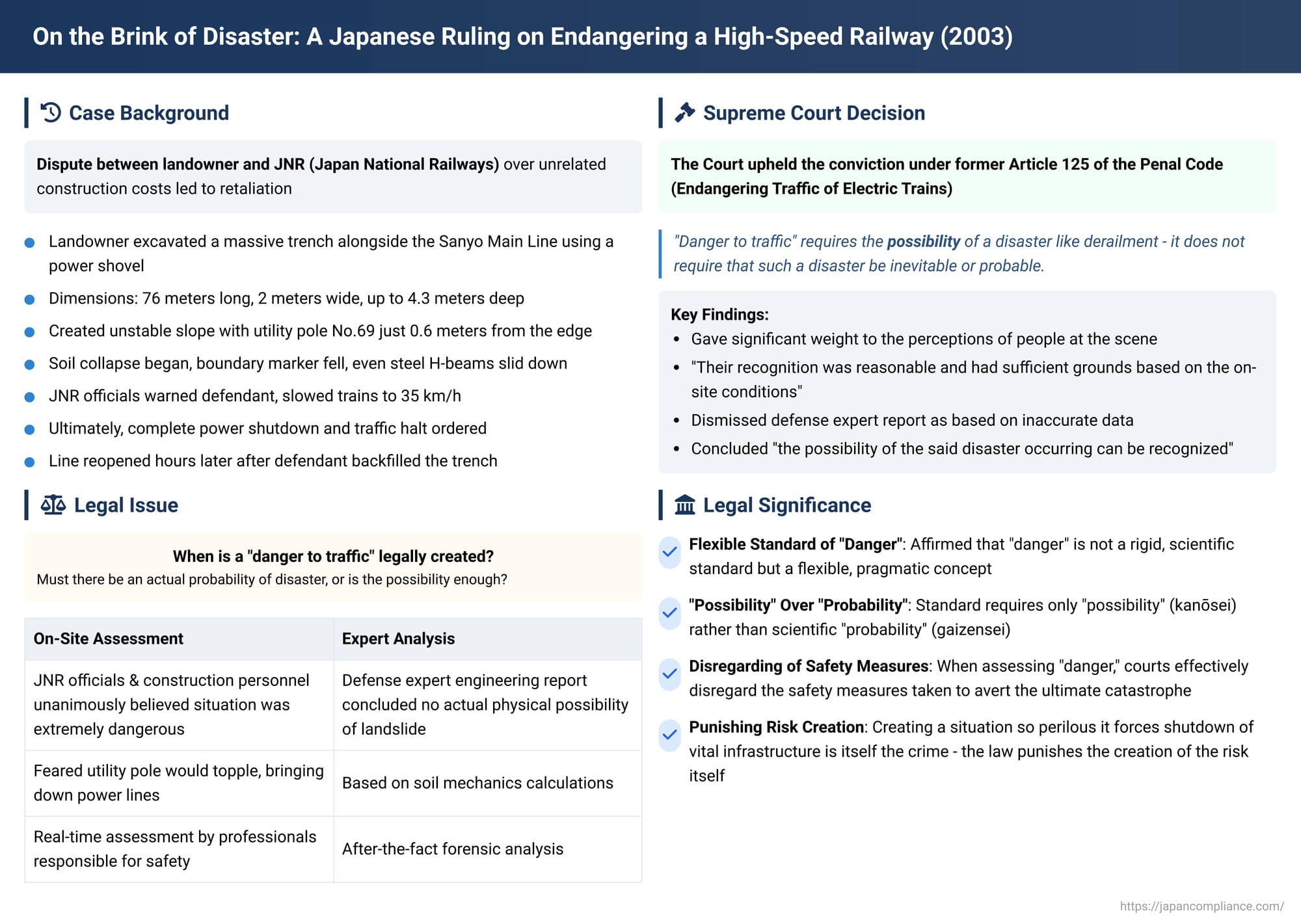

This high-stakes conflict was at the center of a June 2, 2003, decision by the Supreme Court of Japan. The case, involving a dramatic standoff between a landowner with a power shovel and the former Japan National Railways (JNR), provides a fascinating look into the legal definition of "danger to traffic" and the standards by which it is judged.

The Facts: The Landowner's Trench

The incident stemmed from a dispute between the defendant and JNR over construction costs on an unrelated property. In retaliation, the defendant took drastic action against a JNR railway line bordering another piece of land he owned.

- The Act: The defendant hired a power shovel operator and, over the course of an afternoon, excavated a massive trench along the boundary of his property and the Sanyo Main Line, a major railway artery. The resulting excavation was approximately 76 meters long, 2 meters wide, and up to 4.3 meters deep.

- A Perilous Situation: This created a steep, unstable slope next to the railway embankment, which far exceeded JNR's own safety standards. At the most critical point, a railway utility pole (No. 69), essential for the train's overhead power lines, was left teetering just 0.6 meters from the trench's edge. As the excavation progressed, soil began to collapse, a boundary marker fell away, and even steel H-beams that JNR had driven into the ground as a protective measure slid down the unstable slope.

- Emergency Response: JNR officials at the scene, including the head of the local maintenance district, repeatedly warned the defendant to stop. As a precaution, they ordered passing trains to slow to 35 km/h. Ultimately, fearing that the utility pole would collapse and bring the high-voltage catenary wires down onto the tracks, the JNR site manager made a critical decision: he ordered a complete shutdown of power to the line, halting all train traffic. The line was only reopened hours later after the defendant agreed to backfill the trench.

The Legal Standoff: When Is Danger "Real"?

The defendant was charged with Endangering Traffic of Electric Trains (under a former version of Article 125 of the Penal Code), a crime that requires proof that a "danger to traffic" was created. This means a danger of a serious accident (jitsugai), such as derailment, overturning, or collision, not merely a traffic obstruction.

The case presented a classic legal dilemma, as the lower courts were faced with conflicting evidence about the reality of the danger:

- The View from the Ground: The JNR officials and construction personnel on the scene, experienced professionals responsible for the line's safety, unanimously believed the situation was extremely dangerous. They feared a landslide near pole No. 69 would cause it to topple, bringing down the power lines and leading to a potential train derailment.

- The View from the Lab: An expert engineering report, submitted by the defense, analyzed the soil mechanics and concluded the opposite. Based on its calculations, there was no actual physical, engineering possibility of a landslide occurring.

This created the central question for the courts: should they rely on the expert's forensic analysis or the reasonable, real-time assessment of the professionals on site?

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Possibility is Enough

The Supreme Court upheld the conviction, but its reasoning carefully navigated the conflicting evidence. The Court affirmed the established legal principle for this crime:

- "Danger to traffic" requires the possibility of a disaster like derailment.

- However, it does not require that such a disaster be inevitable or probable.

In applying this standard, the Court gave significant weight to the perceptions of the people at the scene. It highlighted the massive scale of the excavation and, crucially, the fact that "JNR employees and construction personnel unanimously recognized that the situation was extremely dangerous." The Court found that "their recognition was reasonable and had sufficient grounds based on the on-site conditions." Based on this, the Court concluded that the "possibility of the said disaster occurring can be recognized." It also dismissed the defense's expert report, finding that its calculations were based on inaccurate data regarding the excavation's shape and location.

Analysis: The Flexible Standard of "Danger"

This decision demonstrates the flexible, pragmatic approach Japanese courts take when defining "danger" in this context. The standard is not a rigid, scientific one.

- "Possibility," Not "Probability": The legal standard is intentionally set lower than a strict, scientific "probability" (gaizensei). This is achieved in part by shifting the perspective of judgment. Instead of requiring the certainty of a top-tier expert, the law is satisfied by the "reasonable apprehension of danger" that an informed ordinary person would feel in the same situation. The High Court's reasoning, which the Supreme Court appeared to lean on, explicitly adopted this viewpoint.

- The Paradox of Safety Measures: A critical insight into this and similar cases is the court's treatment of the emergency safety measures taken by the railway operator. Logically, the fact that JNR slowed the trains and then cut the power made an actual accident almost impossible. If a court were to consider these successful safety measures in its assessment, it would have to conclude that no danger of a disaster actually existed.

- The Implied Rule: Disregarding Averting Actions: The fact that the Court still found a danger existed reveals a long-standing, if often unstated, judicial principle. When assessing whether a "danger to traffic" was created, the courts effectively disregard the very safety measures taken to avert the ultimate catastrophe. The crime is not the final accident; the crime is creating the initial, perilous situation that forces a responsible operator to take drastic emergency action.

Conclusion

The 2003 ruling in this dramatic standoff serves as a powerful affirmation of the law's protective scope over vital public infrastructure. It establishes that "danger to traffic" is a flexible standard, judged not by a purely scientific, after-the-fact analysis but by the reasonable possibility of disaster as perceived at the time. The decision gives immense weight to the judgment of experienced professionals on site and makes it clear that creating a situation so perilous that it forces a major transport operator to shut down its system is, in itself, the crime of endangering traffic. One cannot create a clear and present danger and then claim innocence because the system's own safety protocols worked to prevent the worst from happening. The law punishes the creation of the risk itself.