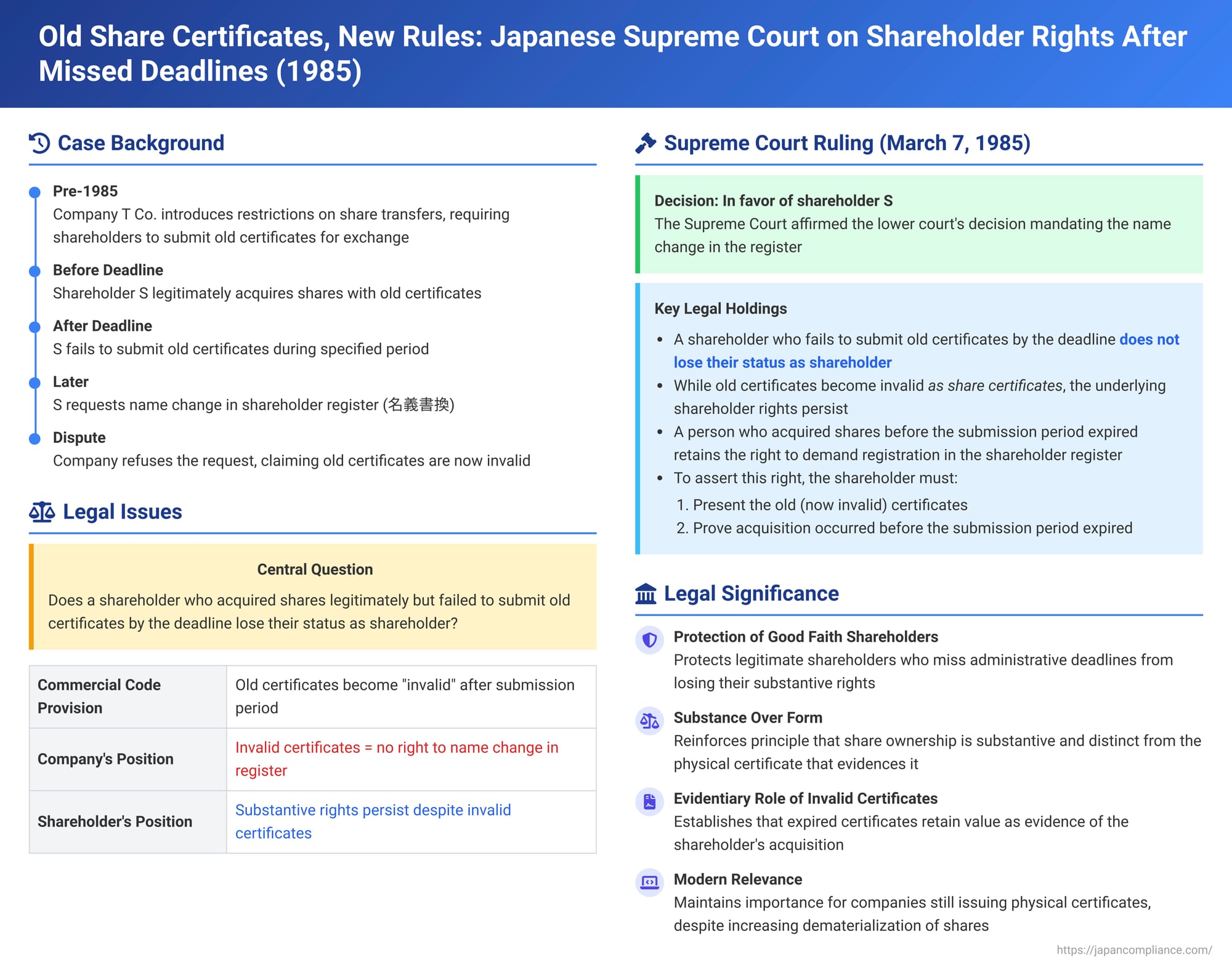

Old Share Certificates, New Rules: Japanese Supreme Court on Shareholder Rights After Missed Deadlines

Date of Judgment: March 7, 1985

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction

For Japanese companies that issue physical share certificates, significant corporate changes—such as amending the articles of incorporation to introduce restrictions on share transfers, or undergoing share consolidations or mergers—often necessitate a formal process of recalling old share certificates and issuing new ones to shareholders. This procedure ensures that the certificates in circulation accurately reflect the current terms and status of the shares. Companies set a specific period during which shareholders must submit their existing certificates. But what happens if a shareholder, for one reason or another, fails to submit their old share certificates by the stipulated deadline? Does this oversight lead to the forfeiture of their shares or the extinguishment of their rights?

This critical question was addressed by the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan in a notable decision on March 7, 1985. The case examined the rights of a shareholder who had acquired shares and received the old certificates before such a corporate change took effect but missed the deadline for submitting those certificates for exchange. The Court's ruling provided important clarifications on the enduring nature of shareholder status despite the invalidation of the old share certificate itself.

The Legal and Procedural Backdrop: Exchanging Share Certificates

Under Japanese corporate law, particularly the Commercial Code provisions applicable at the time of this case (and with analogous procedures existing under the current Companies Act for certain corporate actions), when a company made certain fundamental changes, it triggered a need to update its issued share certificates. For instance:

- Introducing Share Transfer Restrictions: If a company decided to amend its articles of incorporation to require board approval for share transfers—a common practice—this new restriction would need to be printed on the share certificates.

- Other Corporate Actions: Similar certificate renewal processes could be initiated for events like share consolidations, certain acquisitions of shares by the company, mergers, or other reorganizations.

The typical procedure involved:

- Setting a Submission Period: The company would fix a reasonable period (e.g., not less than one month) during which shareholders were required to submit their old share certificates.

- Public Notice and Individual Notifications: The company had to provide public notice of this requirement and the submission period. It also had to individually notify each shareholder and any pledgees recorded in the shareholder register.

- Consequence of Non-Submission: The notices would specify that any share certificates not submitted within the designated period would become invalid.

This process was designed to ensure an orderly transition and to maintain the accuracy of the share certificates in circulation, reflecting the new corporate reality. The core issue addressed by the Supreme Court was the precise legal consequence for a shareholder who failed to comply with the submission requirement.

The Case in Question (Inferred Facts)

While the Supreme Court's judgment focuses on the legal principles, the underlying facts leading to the dispute can be inferred:

- A company, T Co., which issued physical share certificates, resolved to amend its articles of incorporation to impose restrictions on the transfer of its shares.

- Following the legal requirements of the time, T Co. set a specific period during which its shareholders were to submit their existing, unrestricted share certificates. In return, they would receive new certificates that duly noted the transfer restrictions. The company would have also announced that old certificates not submitted by the deadline would become invalid.

- An individual, S, had purchased shares in T Co. and received the old, unrestricted share certificates before the company's resolution to restrict transfers took effect and, critically, before the deadline for submitting these old certificates had passed. S was, therefore, a legitimate transferee of the shares.

- However, S failed to submit these old share certificates to T Co. within the prescribed submission period. As a result, the old certificates held by S technically became "invalid" as per the company's public notice.

- Subsequently, S approached T Co. and requested that the company update its shareholder register (名義書換 - meigishokae) to reflect S as the legal owner of the shares.

- T Co. likely refused this request, perhaps arguing that S no longer held valid share certificates or had failed to comply with the mandatory submission process. This refusal would have prompted S to file a lawsuit.

The Supreme Court's Decision of March 7, 1985

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, ruled in favor of the shareholder, S, affirming the lower court's judgment that had likely mandated the name change. The Court's reasoning was pivotal:

Shareholder Status Persists Despite Invalidated Certificates

The Court's foremost declaration was that even though old share certificates become invalid as share certificates after the submission period expires, the shareholder who failed to submit them does not thereby lose their fundamental status as a shareholder. The underlying rights and ownership of the shares are not automatically extinguished by a procedural lapse concerning the physical certificate.

This principle was held to apply equally to individuals like S, who had legitimately acquired shares (evidenced by the delivery of old certificates) before the share transfer restrictions took effect and before the submission period expired, but had not yet completed the name change in the shareholder register.

The Right to Request a Change of Name in the Shareholder Register

The Supreme Court affirmed that a person who had lawfully become a shareholder before the expiry of the certificate submission period retained the right to demand that their name be entered as the shareholder in the company's official register. The company could not deny this right simply on the grounds that the shareholder was not yet listed in the register or that their old certificate form was now out of date.

The Mechanism for Asserting Rights

The Court outlined how such a shareholder could assert their rights:

- Present the Old Share Certificates: The shareholder must present the old (now technically invalid as a share certificate) share certificates to the company.

- Prove Pre-Deadline Acquisition: Crucially, the shareholder must prove that they acquired the shares through the delivery of these specific old share certificates before the submission period for those certificates expired. Under the Commercial Code provisions applicable at the time, the share transfer restriction typically became effective upon the expiration of this share certificate submission period. Thus, proving acquisition before this deadline also established that the shares were acquired while they were still freely transferable (or under the old terms).

If these conditions were met, the shareholder was entitled to have the name change effected in the register. In making this determination, the Supreme Court referenced and reaffirmed a similar conclusion it had reached in a 1977 precedent.

The Nature and Evidentiary Role of the "Invalid" Old Share Certificate

The Supreme Court's decision highlights a nuanced status for the old share certificate after the submission deadline has passed. While it ceases to be a valid "share certificate" in the sense that it might not be directly negotiable or fully represent the current terms of the shares (which are now reflected in the new-form certificates), it is far from worthless. It transforms into a critical piece of evidence.

Scholarly commentary on this and similar situations has explored different theoretical perspectives on the precise evidentiary role of such an old certificate when presented after the deadline:

- Evidence of Right to New Certificate / Presumption of Ownership: One view is that the old certificate essentially functions as a voucher or a token representing the holder's right to claim a new-form share certificate from the company. Furthermore, under general principles (e.g., Article 131, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act concerning the presumption of rights for a possessor of a share certificate), possession of the old certificate might still carry a legal presumption that the holder is the rightful owner of the underlying shares. From this perspective, presenting the old certificate could be largely sufficient to prove one's entitlement, subject to the company's right to verify its authenticity and the chain of transfer if necessary.

- Mere Documentary Evidence: An alternative view treats the old, unsubmitted certificate more strictly as mere documentary evidence. While important, it would be just one component of the proof required. The shareholder would still bear the burden of demonstrating, potentially through additional evidence, that they legitimately acquired the shares before the critical deadline (i.e., before the transfer restrictions took effect and the submission period ended).

The Supreme Court's 1985 judgment, while emphasizing the need to present the old certificate and prove pre-deadline acquisition, did not explicitly delve into the finer points of these doctrinal distinctions. Its focus was more pragmatic: the old certificate, coupled with proof of the timing of its acquisition, serves to establish the shareholder's legitimate claim to the shares and, consequently, to registration in the shareholder register.

Rationale and Broader Implications

The Supreme Court's decision is significant for several reasons:

- Protection of Bona Fide Acquirers: It protects individuals who have legitimately purchased shares but, perhaps through oversight or lack of awareness, miss an administrative deadline related to the physical form of their share certificates.

- Balancing Interests: The ruling strikes a balance between the company's legitimate interest in maintaining an orderly share administration system (which includes updating certificate forms) and the substantive, vested rights of its shareholders.

- Substance over Form: It reinforces the legal principle that share ownership is a substantive right that is distinct from the physical piece of paper (the share certificate) that traditionally evidences it. The invalidation of an outdated form of certificate does not automatically negate the underlying ownership. This is particularly pertinent when the need to change certificate forms is triggered by the company's own actions.

Relevance in Modern Japanese Company Law

While the specific case was decided under the older Commercial Code, its principles have lasting relevance.

- Continuing Procedures: The current Japanese Companies Act still provides for procedures to recall and reissue share certificates in various situations, such as share consolidations, certain types of share acquisitions, and corporate reorganizations (e.g., Article 219 of the Companies Act). The fundamental question of how to treat shareholders who are late in submitting their old certificates can still arise for companies that issue them.

- Dematerialization of Shares: It's important to note that the prevalence of physical share certificates has significantly decreased in Japan with the widespread adoption of the book-entry transfer system for shares of listed companies and many unlisted ones. In a book-entry system, ownership and transfers are recorded electronically, and issues related to physical certificates are less common.

- Enduring Principles: Nevertheless, for companies that continue to issue physical share certificates, this Supreme Court precedent offers vital guidance. The core principles—that shareholder status is not lightly lost, that substance should prevail over minor procedural lapses where rights are clearly established, and that old certificates can serve as key evidence of title—remain important.

Conclusion

The March 7, 1985, Supreme Court decision reflects a practical and equitable approach to a common procedural challenge in corporate administration. It clarifies that while companies can and must manage their share certificate systems, administrative deadlines related to the form of those certificates do not automatically disenfranchise shareholders who have legitimately acquired their shares. The ruling ensures that substantive shareholder rights, once validly obtained, are not easily extinguished by a failure to exchange one piece of paper for another within a set timeframe, provided the shareholder can duly prove their timely acquisition. This judgment underscores the resilience of shareholder status and provides a fair pathway for shareholders to perfect their registration even after a procedural misstep.