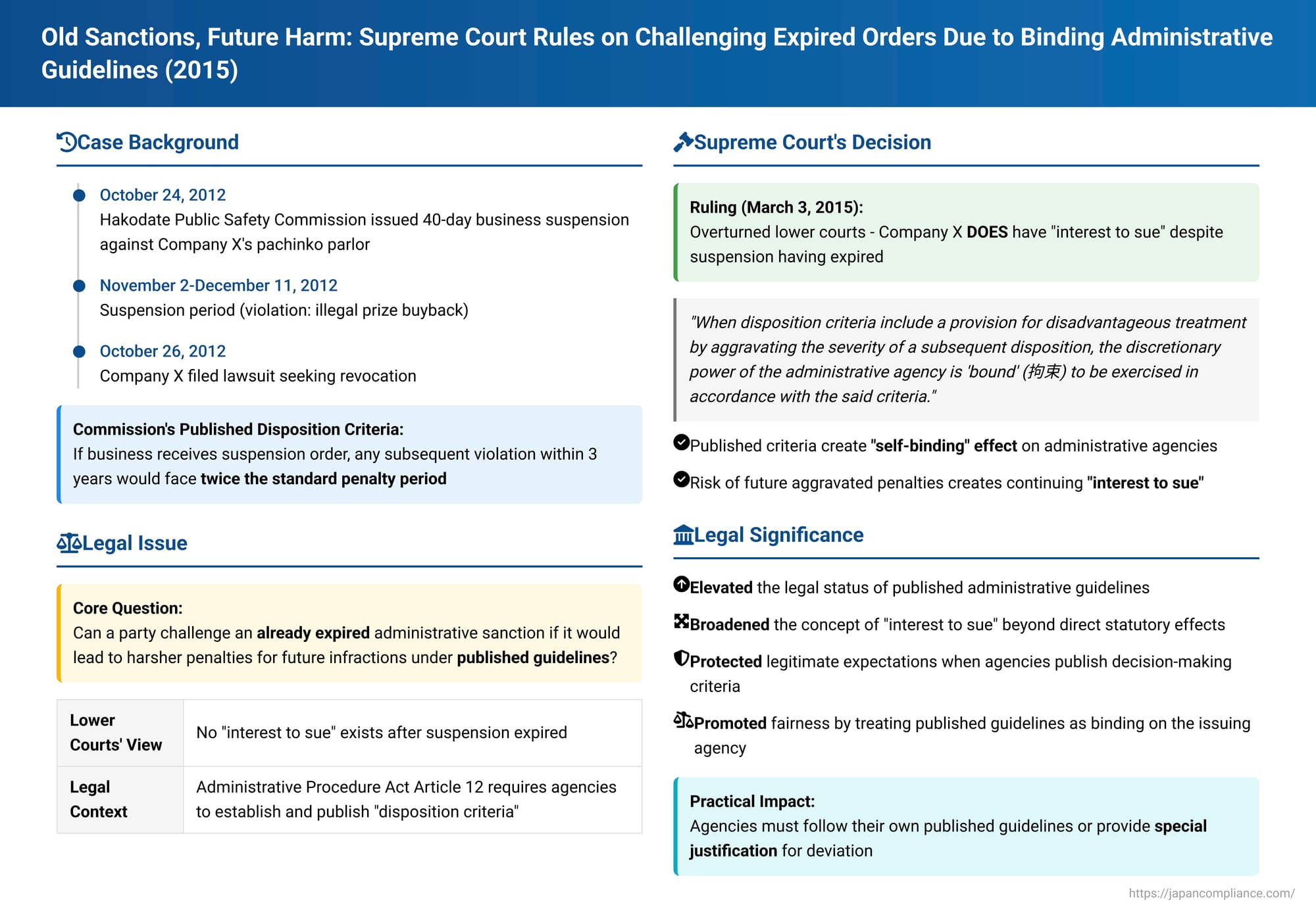

Old Sanctions, Future Harm: Supreme Court Rules on Challenging Expired Orders Due to Binding Administrative Guidelines

Judgment Date: March 3, 2015, Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

A fundamental principle of litigation is that a lawsuit should address a live controversy. Generally, if the direct effects of an administrative sanction, such as a business suspension, have expired, a legal challenge to that sanction might be dismissed for lacking a continuing "interest to sue" (訴えの利益 - uttae no rieki). However, what if that expired sanction could lead to more severe penalties for future infractions due to the administrative agency's own published guidelines? A 2015 Supreme Court decision tackled this question, significantly clarifying the legal weight of such administrative disposition criteria and their impact on a party's ability to continue a lawsuit.

Administrative Rules and Fair Process: Disposition Criteria in Japan

Japan's Administrative Procedure Act (APA) plays a crucial role in ensuring fairness and transparency in administrative actions. Article 12, Paragraph 1 of the APA requires administrative agencies to endeavor to establish "disposition criteria" (処分基準 - shobun kijun) and make them public. These criteria are standards necessary for an agency to determine, in accordance with applicable laws and regulations, whether to issue an adverse disposition (不利益処分 - furieki shobun – such as a business suspension order) or what kind of adverse disposition to issue.

The purpose of requiring agencies to set and publish these criteria is multifaceted:

- To ensure fairness in administrative operations.

- To enhance transparency in the decision-making process.

- To contribute to the protection of the rights and interests of individuals and businesses who may be subject to such dispositions.

These disposition criteria often detail how an agency will exercise its discretion, for example, by outlining standard penalties for certain violations and specifying how penalties might be increased for repeat offenses.

The Pachinko Parlor Suspension: Facts of the Case

The case involved Company X, which operated pachinko parlors under a license from the Hakodate Area Public Safety Commission (hereinafter "the Commission"), an arm of Y (Hokkaido Prefecture). On October 24, 2012, the Commission issued a business suspension order ("the Disposition") against Company X for one of its establishments. The suspension was for a period of 40 days, from November 2 to December 11, 2012. The reason for the Disposition was a finding that A, a representative of Company X, had engaged in the illegal practice of buying back prizes from customers, which is a violation of Article 23, Paragraph 1 of the Act on Control and Improvement of Amusement and Entertainment Business (Fūeihō). The suspension order itself was issued based on Article 26, Paragraph 1 of the Fūeihō.

Crucially, the Hakodate Area Public Safety Commission had established and publicly published its own "Regulations Concerning Standards for Disposition, etc., such as Business Suspension Orders Based on the Act on Control and Improvement of Amusement and Entertainment Business" ("the Criteria"). These Criteria, serving as disposition criteria under APA Article 12, specified upper limits, lower limits, and standard periods for business suspensions depending on the nature of the violation. Significantly, the Criteria included provisions for aggravating sanctions for repeat offenders. Article 10, Paragraph 2 stipulated that if a business had received a suspension order within the past three years, the upper and lower limits for a subsequent suspension period would be determined by multiplying the standard limits by twice the number of prior suspensions. Article 11, Paragraph 1, Item 2 specified that the standard period for such a repeat offense would be twice the normal standard period.

Company X filed a lawsuit on October 26, 2012, seeking the revocation of the 40-day business suspension Disposition. By the time the case reached the higher courts, the 40-day suspension period had, of course, expired. Y (Hokkaido Prefecture) argued as a preliminary issue that because the suspension period had passed, the direct effect of the Disposition was extinguished, and therefore Company X no longer had a legal "interest to sue" for its revocation.

The Sapporo District Court (First Instance) agreed with Y and dismissed X's suit for lack of interest to sue. The Sapporo High Court (Second Instance) upheld this dismissal. Company X then successfully petitioned the Supreme Court for a final review.

The Supreme Court's Decision (March 3, 2015): Lingering Harm Creates Interest to Sue

The Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, overturned the lower courts' judgments and remanded the case back to the Sapporo District Court for a trial on the merits. The Supreme Court found that Company X did retain an "interest to sue" even after the 40-day suspension period had expired, precisely because of the existence and nature of the Commission's published Disposition Criteria.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

I. The Legal Weight of Published Disposition Criteria

The Supreme Court began by emphasizing the significance of disposition criteria established under APA Article 12:

- "Disposition criteria established and made public based on Article 12, Paragraph 1 of the [Administrative Procedure] Act are not merely for the administrative agency's administrative operational convenience; they should be considered as established and made public to ensure fairness and transparency in the decision-making process concerning adverse dispositions and to contribute to the protection of the rights and interests of the addressee of such dispositions."

II. Administration Bound by Its Own Rules (The "Self-Binding" Principle)

Building on this, the Court articulated a principle of administrative self-binding:

- "Therefore, when an administrative agency has established and made public disposition criteria under the said paragraph which include a provision for disadvantageous treatment by aggravating the severity of a subsequent disposition based on the receipt of a prior disposition, if the said administrative agency handles a subsequent disposition differently from the provisions of the said disposition criteria, then from the perspective of the requirement for fair and equal treatment in the exercise of discretionary power and the protection of the addressee's reliance on the content of the criteria, etc., unless there are special circumstances that should be recognized as making it appropriate to handle it differently from the provisions of the said disposition criteria, such handling will be deemed an excess or abuse of discretionary power."

- "In this sense, the discretionary power of the said administrative agency in a subsequent disposition is 'bound' (き束されており - kisoku sarete ori) to be exercised in accordance with the said disposition criteria, and when a person who has received a prior disposition becomes the subject of a subsequent disposition, it can be said that, absent the aforementioned special circumstances, the prescribed aggravation of severity will be applied according to the provisions of the said disposition criteria."

III. Future Disadvantage Due to Criteria Creates Continuing Interest to Sue

The Court then linked this binding nature of the criteria to the "interest to sue":

- "Considering the above, when disposition criteria established and made public under Article 12, Paragraph 1 of the Administrative Procedure Act include a provision for disadvantageous treatment by aggravating the severity of a subsequent disposition based on the receipt of a prior disposition, a person who has received a disposition that constitutes such a prior disposition, if they could become subject to a disposition that constitutes such a subsequent disposition in the future, has a legal interest to be restored by the revocation of the said prior disposition even after the effects of the said prior disposition have ceased due to the passage of time, for as long as they are subject to receiving such disadvantageous treatment under the provisions of the said disposition criteria."

IV. Application to Company X's Case

Applying this principle to the facts of the case:

- Company X, due to the 40-day business suspension Disposition, was subject to the provisions of the Commission's published Criteria. These Criteria stipulated that the severity of any future business suspension orders against X would be aggravated if such future orders were issued within three years of the current Disposition.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded: "Within the three-year period after the present Disposition during which the severity of future business suspension orders should be aggravated according to the provisions of the present Regulations, which are disposition criteria established and made public under Article 12, Paragraph 1 of the Administrative Procedure Act, it should be said that the appellant [Company X] still has a legal interest to be restored by the revocation of the present Disposition."

Significance: Elevating the Status of Administrative Guidelines

This 2015 Supreme Court decision is highly significant for several reasons:

- Strengthening the Legal Effect of Disposition Criteria: It strongly affirms that publicly established disposition criteria under APA Article 12 have a "self-binding" effect on administrative agencies. While these criteria are administrative rules rather than laws enacted by the legislature, agencies are not free to ignore them arbitrarily. A deviation without special justification can be deemed an abuse of discretion. This reinforces the principles of fairness, equality, and legitimate expectations in administrative practice.

- Broadening the Concept of "Interest to Sue": The ruling expands the circumstances under which an "interest to sue" can be found to exist even after the direct, immediate effects of an administrative sanction have expired. It clarifies that a demonstrable risk of future disadvantage stemming directly from published administrative guidelines can be sufficient to maintain a legal challenge. This is a notable development because previous Supreme Court cases often required such future disadvantage to be rooted in a statutory provision (e.g., a law mandating harsher penalties for repeat offenders) rather than administrative criteria.

- Promoting Administrative Fairness and Transparency: By giving legal consequence to published criteria, the decision encourages administrative agencies to act consistently and predictably. This enhances the transparency of administrative decision-making and allows individuals and businesses to better understand how administrative discretion is likely to be exercised, fostering reliance on published rules.

Broader Implications

The PDF commentary accompanying this case suggests that the Supreme Court's reasoning regarding the binding nature of disposition criteria could have implications beyond just situations involving the aggravation of penalties for prior offenses. It might influence how courts review administrative adherence to such criteria in a wider array of discretionary decisions. For instance, the principles articulated could potentially extend to how agencies apply "examination criteria" (審査基準 - shinsa kijun) under APA Article 5, which guide the processing of applications for licenses and permits.

Conclusion

The 2015 Supreme Court decision in the pachinko parlor suspension case provides crucial clarification on the concept of "interest to sue" when the primary effects of an administrative sanction have passed. It establishes that if an agency's publicly established disposition criteria (published under the Administrative Procedure Act) mandate that a past sanction will lead to more severe penalties or other disadvantages for future infractions, the individual or entity subject to that past sanction retains a cognizable legal interest in challenging its validity as long as the risk of such future aggravated treatment persists.

This judgment significantly reinforces the legal status and importance of administrative disposition criteria, emphasizing that agencies are generally bound by their own published rules. By doing so, it promotes fairness, transparency, and predictability in administrative actions, and broadens the avenues for effective judicial review for those who may face lingering consequences from past administrative sanctions.