Old Gifts, New Problems: Reserved Portion Claims and Gifts to Heirs in Japan

Decision Date: March 24, 1998

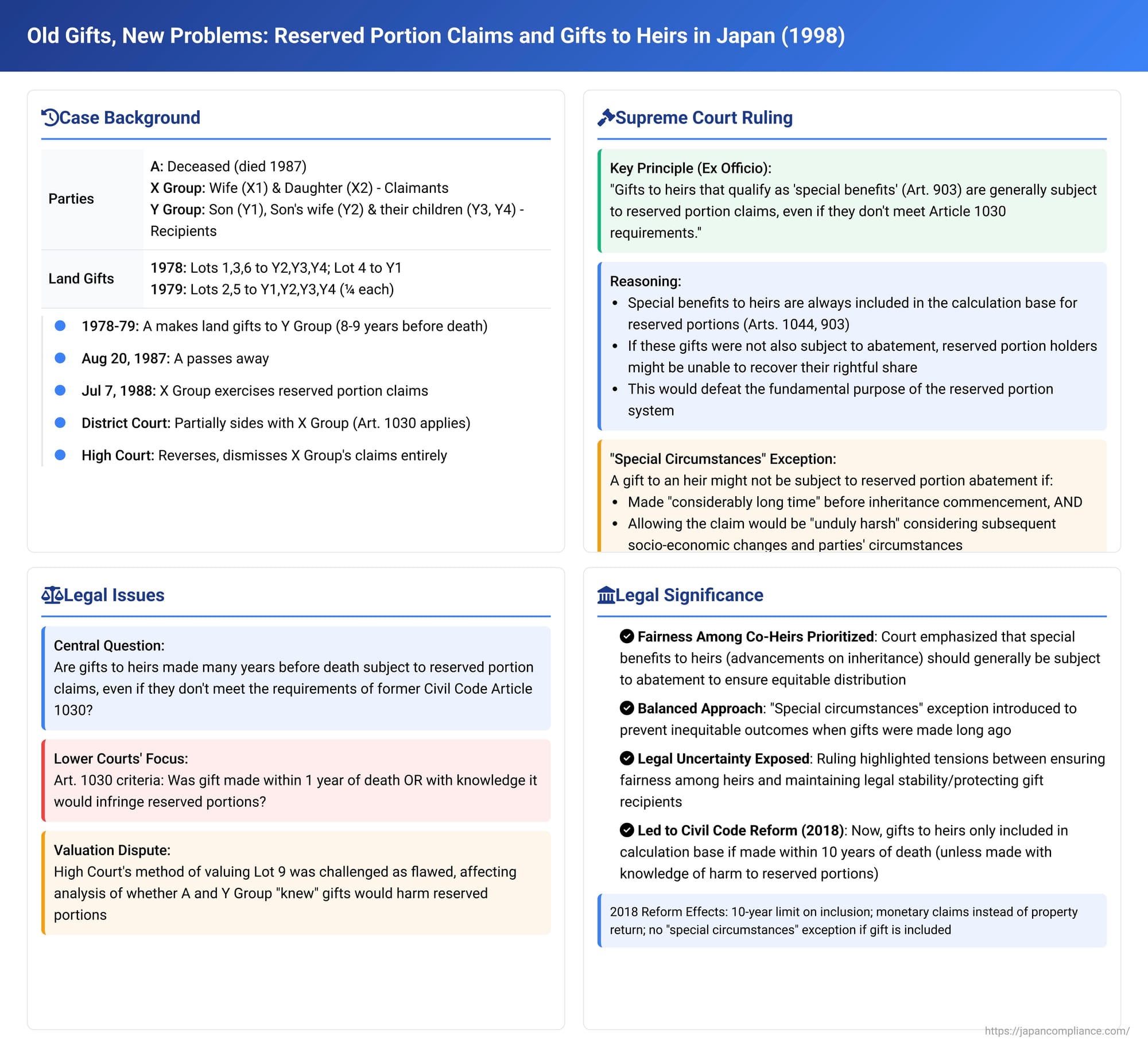

On March 24, 1998, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment addressing the complex interplay between lifetime gifts made to heirs—often decades before the giver's death—and the legally reserved portion (iryūbun) claims of other heirs. This case tackled a crucial question under Japan's (pre-2018 reform) Civil Code: Can gifts considered "special benefits" to an heir be clawed back to satisfy reserved portion rights, even if those gifts were made long ago and without any apparent intent to harm other heirs at the time?

I. The Factual Landscape: A Family Inheritance Dispute

The case involved the estate of A, who passed away on August 20, 1987. His heirs were his wife, X1, his eldest daughter, X2 (collectively, the "X Group"), and his eldest son, Y1.

Many years prior to his death, A had made substantial lifetime gifts of land:

- On October 16, 1978 (approximately 9 years before his death), A gifted three parcels of land (Lots 1, 3, and 6) to Y1's wife (Y2) and their children (Y3 and Y4). On the same day, A gifted another parcel (Lot 4) directly to Y1.

- On January 16, 1979 (approximately 8 years before his death), A gifted two more parcels (Lots 2 and 5) to Y1, Y2, Y3, and Y4, each receiving a one-quarter share in these properties.

(Y1, Y2, Y3, and Y4 are collectively referred to as the "Y Group").

The X Group (A's wife and daughter) contended that these lifetime gifts to the Y Group had infringed upon their legally reserved portion of A's estate. Consequently, on July 7, 1988, they formally exercised their reserved portion claim (iryūbun gensai seikyūken) against the Y Group. They subsequently filed a lawsuit seeking the transfer registration of the co-ownership shares they claimed to have recovered in Lots 2 and 5 due to their reserved portion claim. Y1 also filed a counterclaim for damages against X1, alleging unauthorized sale of Y1's property, but this was dismissed by the lower courts and not appealed further.

II. The Journey Through Lower Courts: Conflicting Interpretations

A. First Instance Court (Sendai District Court)

The District Court partially sided with the X Group. It focused on the 1979 gifts (Lots 2 and 5) and noted that, at the time these gifts were made, their value significantly exceeded the value of A's remaining properties (Lots 7-9). Based on this disparity, the court inferred that A and the Y Group must have known that these gifts would infringe upon the X Group's reserved portion rights. Under the (former) Civil Code Article 1030, gifts made with such knowledge, even if made more than one year before death, could be subject to reserved portion claims.

B. Appellate Court (Sendai High Court)

Both parties appealed. The High Court reversed the District Court's decision and dismissed the X Group's claims entirely. The High Court's reasoning was:

- It found that, at the time of the gifts, A actually possessed other assets, including Lot 9 (which it valued highly using a specific method), the total value of which exceeded the value of the gifted lands.

- Given this, and the fact that over eight years had passed between the gifts and A's death, with no apparent risk of A's overall assets diminishing at the time of the gifts, the High Court concluded that the gifts were not made with the knowledge that they would cause loss to the X Group's reserved portion rights.

- Therefore, according to former Civil Code Article 1030, these gifts were not subject to reserved portion abatement claims.

The X Group appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that the High Court had erred in its valuation method for Lot 9 and had, as a consequence, misinterpreted the "knowledge of causing harm" requirement under former Article 1030.

III. The Supreme Court's Decisive Intervention

The Supreme Court found merit in the X Group's arguments regarding the appellate court's flawed valuation of Lot 9, deeming this error sufficient to warrant overturning the High Court's judgment on the main claim. However, the Supreme Court went further and, ex officio (on its own initiative), laid down a crucial legal principle concerning gifts to heirs and reserved portion claims under the former Civil Code:

A. The General Rule: Gifts to Heirs are Subject to Abatement

The Court declared that gifts made by a deceased person to their heirs, which qualify as "special benefits" under former Civil Code Article 903(1) (effectively, advancements on inheritance), are generally subject to reserved portion abatement claims. This applies even if such gifts do not meet the specific requirements of former Civil Code Article 1030 (i.e., made within one year prior to the commencement of inheritance, or made at an earlier time when both parties knew the gift would prejudice reserved portion holders).

B. Rationale for the General Rule

The Supreme Court's reasoning was rooted in the structure and purpose of the reserved portion system:

- Inclusion in Calculation Base: Gifts constituting special benefits to heirs are always included when calculating the total value of the estate that forms the basis for determining reserved portion amounts (as per former Civil Code Articles 1044 and 903).

- Preventing Frustration of the System: If these gifts, despite being included in the calculation base, were not subject to abatement simply because they didn't meet Article 1030's conditions, a problematic situation could arise. Specifically, an heir whose reserved portion is infringed might find that there are no (or insufficient) other gifts or testamentary bequests that are subject to abatement. This would leave the infringed heir unable to recover their rightful reserved portion, thereby defeating the fundamental purpose of the reserved portion system, which is to guarantee a minimum share to certain heirs.

C. The "Special Circumstances" Exception

While establishing this general rule, the Supreme Court also introduced an important exception:

A gift to an heir, even if it's a special benefit, might not be subject to a reserved portion abatement claim if "special circumstances" exist. Such circumstances would be present if:

- The gift was made a "considerably long time" before the commencement of inheritance; and

- Considering subsequent changes in socio-economic conditions and the personal circumstances of the heirs and other related parties, allowing the reserved portion claim against this old gift would be "unduly harsh" (koku) to the recipient heir.

D. Application to the Present Case and Remand

In applying this principle to the facts, the Supreme Court noted that the gifts of Lot 4 and shares in Lots 2 and 5 to Y1 (an heir) were presumptively special benefits under Article 903(1). The High Court had erred by immediately concluding these were not subject to abatement without first considering whether any "special circumstances" (that would make abatement unduly harsh on Y1) existed.

Consequently, the Supreme Court quashed the relevant parts of the High Court's judgment and remanded the case to the Sendai High Court for a retrial. This retrial would need to correctly value the properties and apply the legal principle articulated by the Supreme Court, including an examination of any potential "special circumstances."

IV. Analysis and Long-Term Implications

This 1998 Supreme Court decision was highly significant as it clarified a contentious issue under the old Civil Code: the abatability of gifts made to heirs many years before death.

A. Prioritizing Fairness Among Co-Heirs

The ruling emphasized the importance of fairness among co-heirs, a core tenet of Japan's inheritance law. Special benefits to heirs are often viewed as "advancements on their inheritance". By holding that such gifts are generally included in the reserved portion calculation base and are also subject to abatement, the Court sought to ensure that disparities arising from large lifetime gifts to one heir do not unfairly diminish the legally protected shares of other heirs. According to this logic, the stricter conditions of former Article 1030 (one-year rule or knowledge of harm) would primarily apply to gifts made to non-heirs.

B. The "Special Circumstances" Exception: A Balancing Mechanism

The introduction of the "special circumstances" exception was the Court's attempt to inject flexibility and prevent inequitable outcomes. Allowing abatement of very old gifts without any qualification could lead to significant hardship for the recipient heir, especially considering factors like:

- The passage of many decades.

- Substantial changes in property values or economic conditions.

- The recipient heir having integrated the gifted property into their life and financial planning over a long period.

- Difficulties in proving the circumstances surrounding very old gifts.

The exception aimed to mitigate these concerns by allowing courts to consider the specific facts of each case.

C. Criticisms and Unresolved Issues under the 1998 Ruling's Framework

Despite its intentions, the framework established by the 1998 Supreme Court ruling presented certain challenges, as highlighted in legal commentary:

- Legal Stability and Impact on Third Parties: A significant concern was that including very old gifts made to heirs in the reserved portion calculation base could create unpredictability and negatively affect third parties. For example, if a large, decades-old gift to an heir (Heir A) significantly inflates the calculation basis for the reserved portion, a more recent legatee or donee (Party X, who is not an heir) might suddenly face a reserved portion claim from another heir (Heir B) that wouldn't have existed otherwise. Party X would typically have no knowledge of the old gift to Heir A and could be unfairly prejudiced. This could undermine the stability of transactions.

- Potential Inconsistency in Ensuring Fairness: The "special circumstances" exception, while designed to protect recipient heirs from harsh outcomes, could paradoxically lead to the very unfairness the general rule sought to prevent. If a large, old gift to an heir is included in the calculation base but then deemed non-abatable due to "special circumstances," other heirs whose reserved portions are infringed might still be unable to recover their full entitlements if that non-abatable gift was the primary asset causing the infringement.

These issues highlighted the inherent tension between ensuring fairness among heirs, protecting the interests of reserved portion holders, and maintaining legal stability for recipients of gifts and third parties.

D. The 2018 Civil Code Reforms: A New Approach

Recognizing the complexities and potential issues arising from the previous framework (including those underscored by this 1998 judgment), Japan undertook significant reforms to its inheritance law in 2018 (effective 2019). These reforms introduced a different approach to handling gifts to heirs in the context of reserved portion claims:

- Time Limit for Including Gifts to Heirs: The new Civil Code (Art. 1044(1) and (3)) now generally limits the inclusion of gifts to heirs (specifically, gifts for marriage, adoption, or as capital for livelihood) in the reserved portion calculation base to those made within ten years prior to the commencement of inheritance. Gifts made before this ten-year period are only included if both the donor and the donee knew at the time of the gift that it would prejudice the reserved portion rights of other heirs. This reform prioritizes legal stability by preventing very old, potentially forgotten gifts from unexpectedly affecting reserved portion calculations, though it represents a step back from the goal of equalizing all past advancements among heirs.

- No "Special Circumstances" Exception to Abatement Liability: Under the new law, if a gift is included in the calculation basis for the reserved portion, the recipient of that gift (or testamentary bequest) is liable to pay the monetary equivalent of the infringed reserved portion up to the value of the benefit they received (New Civil Code Art. 1047(1)). There is no longer a "special circumstances" exception that would allow an included gift to escape this liability. This ensures that if an heir's reserved portion is determined to be infringed by an included gift, they have a clearer path to recovery, as the primary recipients of such benefits are now unequivocally responsible. (The reserved portion claim itself has also been reformed into a monetary claim rather than a claim for restoration of property).

V. Conclusion: An Evolving Balance in Inheritance Law

The Supreme Court's March 24, 1998, decision was a crucial attempt under the former Civil Code to strike a balance between the principle of ensuring that heirs receive their legally protected reserved portions and the need to avoid unduly harsh consequences for recipients of very old gifts. It affirmed the general abatability of special benefits to heirs while introducing a "special circumstances" safety valve. However, the inherent complexities and potential for unintended consequences highlighted by this ruling contributed to the impetus for the 2018 inheritance law reforms. These reforms have now established a new framework that seeks to achieve a different balance, primarily by imposing time limits on the inclusion of gifts to heirs and clarifying liability for infringement, thereby aiming for greater legal certainty in this intricate area of law.