Offset of Gains and Losses: Japan's Supreme Court Revisits Damages Calculation for Lost Pensions (March 24, 1995)

In its landmark 24 Mar 1995 ruling, Japan’s Supreme Court limited the offset of survivor pensions in tort damages, allowing deductions only for payments already received or definitively due—reshaping damages calculation for wrongful‑death cases.

TL;DR

Japan’s Supreme Court Grand Bench (24 Mar 1995) ruled that, in wrongful‑death tort cases, only survivor‑pension payments already received or unquestionably due by the close of trial may be deducted from damages for lost retirement pensions. The decision overruled earlier precedents, raised potential recovery for plaintiffs, and set a new “certainty‑equivalent” standard for offsets.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: Fatal Accident and Competing Pension Claims

- Lower Court Ruling: Offsetting Only Paid Benefits

- The Supreme Court’s Decision (March 24 1995 – Grand Bench)

- The Dissenting Opinions

- Implications and Significance

- Conclusion

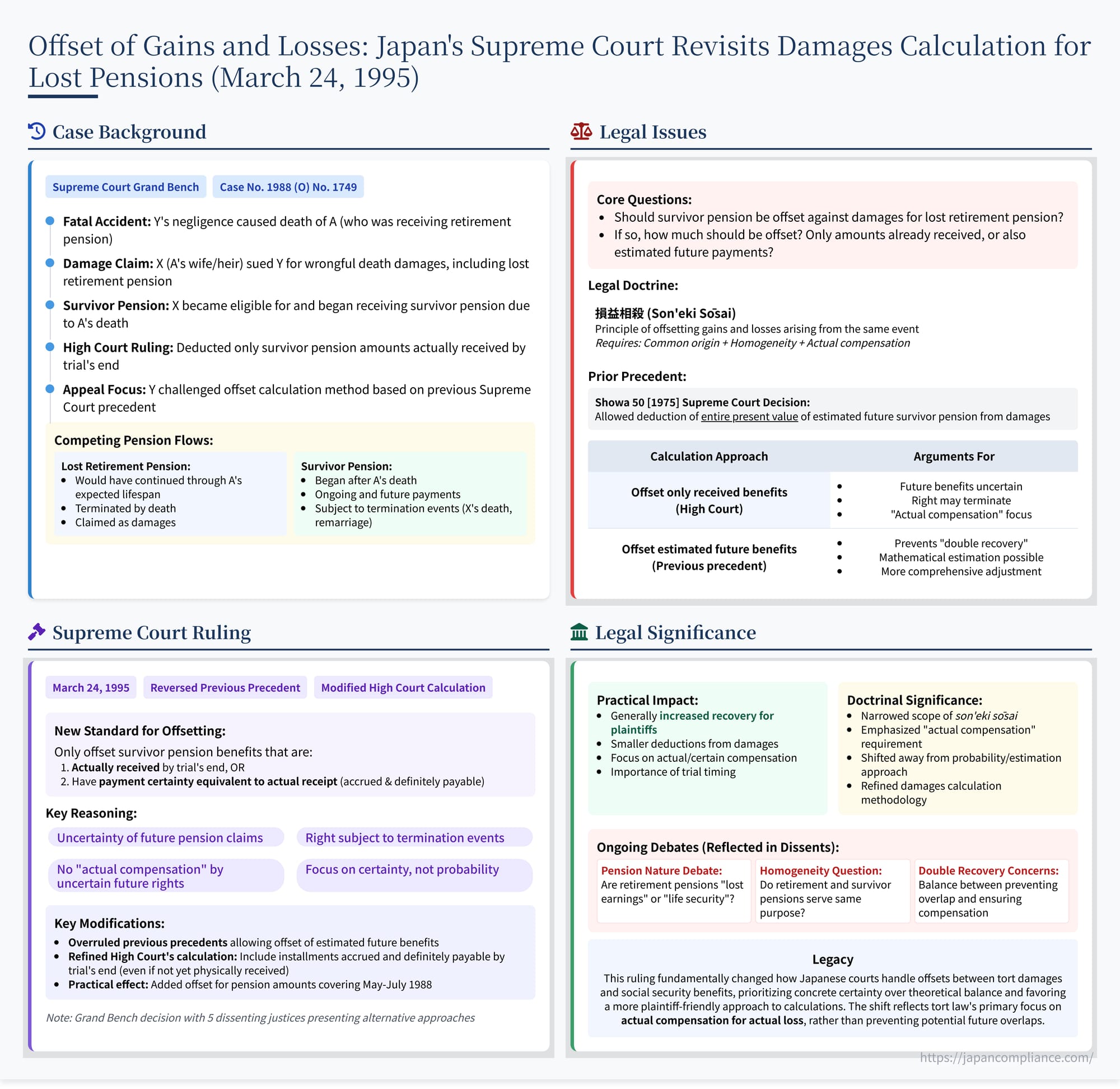

On March 24, 1995, the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment that revised the method for calculating damages in wrongful death tort cases involving public pensions (Case No. 1988 (O) No. 1749, "Damages Claim Case"). The case specifically addressed how survivor pension benefits received by an heir should be treated when calculating damages claimed for the deceased's lost retirement pension benefits, under the legal principle of son'eki sōsai (offsetting gains and losses). Departing from its own prior precedents, the Court ruled that only survivor pension benefits actually received or whose payment has become definitively certain by the end of the trial should be deducted from the damages, rejecting the previous approach of deducting the estimated present value of future survivor benefits. This decision marked a major shift in how future, uncertain benefits are considered in tort damage calculations in Japan.

Factual Background: Fatal Accident and Competing Pension Claims

The case arose from a fatal traffic accident and the subsequent calculation of damages:

- The Accident and Victim: A was killed in a traffic accident caused by the negligence of the appellant, Y. Prior to the accident, A was receiving a retirement pension under the Local Public Employees, etc. Mutual Aid Association Act (the MAA Act, referring to the version before the 1985 amendments).

- The Claimant: The appellee, X, was A's wife and heir.

- The Damages Claim: X sued Y for wrongful death damages. A significant component of the claim was compensation for the loss of the retirement pension payments that A would have received during his remaining expected lifespan had the accident not occurred. This "lost retirement pension" was claimed as part of A's damages, inherited by X.

- Survivor Pension: As a result of A's death caused by the accident, X also became eligible for and began receiving a survivor pension under the same MAA Act. This survivor pension is designed to support the livelihood of dependents after a member's death.

- The Offset Issue: The central legal issue was whether the survivor pension benefits X received (and would continue to receive) should be deducted from the damages X was claiming for A's lost retirement pension. This invoked the legal doctrine of son'eki sōsai, which aims to prevent plaintiffs from receiving a windfall by deducting benefits received due to the same tortious event from the damages awarded. The dispute specifically focused on how much of the survivor pension should be deducted – only the amounts already paid, or also an estimated value of future payments?

Lower Court Ruling: Offsetting Only Paid Benefits

The Osaka High Court, acting as the lower appellate court, calculated the damages based on A's lost retirement pension (X's inherited portion). It acknowledged that the survivor pension received by X arose from the same event (A's death) and had a similar purpose (livelihood support), thus requiring an offset under the son'eki sōsai principle. However, it ruled that only the survivor pension installments X had actually received up to the close of oral arguments in the High Court should be deducted. It rejected Y's argument, which was based on then-existing Supreme Court precedent (specifically a Showa 50 [1975] decision), that the entire present value of X's future survivor pension entitlement (estimated over A's remaining life expectancy) should be deducted. Y appealed this specific point regarding the scope of the offset to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (March 24, 1995 - Grand Bench)

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court, in its judgment dated March 24, 1995, took the significant step of overruling its prior precedents and largely agreeing with the High Court's approach regarding the limited scope of the offset, although it slightly modified the calculation endpoint.

1. Reaffirming the Purpose of Tort Damages and Son'eki Sōsai:

The Court began by reaffirming the fundamental principles:

- Tort damages aim to compensate for the actual loss suffered by the victim (or their heirs) and restore them, financially, to the position they would have been in had the tort not occurred.

- The doctrine of son'eki sōsai (offsetting gains and losses) applies when the same tortious event causes both damage and a benefit to the victim/heir. To prevent overcompensation and ensure fairness, the monetary value of the benefit should be deducted from the damages, but only if the benefit and the loss share a common origin and are homogeneous in nature (dōshitsusei - 同質性).

- Crucially, this offset adjustment should be limited to the extent that the victim's loss can be said to have been "actually compensated" (genjitsu ni hoten sareta) by the benefit received.

2. The Problem with Offsetting Future Uncertain Benefits:

The Court then addressed the core issue: can the mere acquisition of a right to receive future benefits (like a survivor pension) be considered "actual compensation" sufficient to justify offsetting its estimated value from current damages?

- Uncertainty of Claims: The Court stated that acquiring a claim (債権 - saiken) against a third party due to the tort does not, in principle, automatically warrant an offset. This is because claims inherently involve uncertainty regarding their performance or payment.

- Uncertainty of Survival: This uncertainty is particularly pronounced for claims involving continuous future payments, like pensions, where the survival of the right itself is often contingent on future events (e.g., the recipient staying alive, not remarrying). The Court noted that survivor pensions under the MAA Act are subject to termination upon the recipient's death, remarriage, etc. (citing Art. 96).

- No "Actual Compensation" by Uncertain Future Rights: Because of these inherent uncertainties regarding both payment and the right's continued existence, acquiring the right to receive future, contingent pension installments cannot be equated with having received actual compensation for the present loss (the lost retirement pension).

3. The New Standard: Certainty Equivalent to Actual Receipt:

Based on this reasoning, the Court established a new standard for offsetting benefits derived from acquired rights:

- Offsetting under son'eki sōsai is only permissible for the value of benefits that have been actually received (現実 に履行された - genjitsu ni rikō sareta) OR benefits whose survival and performance are certain to a degree equivalent to actual receipt (これと同視し得る程度にその存続及び履行が確実である - kore to dōshi shiuru teido ni sono sonzoku oyobi rikō ga kakujitsu de aru).

4. Applying the Standard to Survivor Pensions:

Applying this standard to the case:

- Homogeneity: The Court affirmed that retirement pensions and survivor pensions under the MAA Act share the same fundamental purpose and function – providing livelihood support – and thus possess the necessary homogeneity for offset to be considered.

- Certainty of Performance: Payment by the MAA (a reliable public entity) means the performance of due pension installments is practically certain.

- Uncertainty of Survival: However, the survival of the right to future installments remains uncertain due to potential disqualifying events (death, remarriage).

- Conclusion on Offset Amount: Therefore, only survivor pension installments that (a) have already been paid to X, or (b) whose eligibility period has accrued and payment has become definitively due by the close of oral arguments in the final fact-finding court (the High Court), meet the standard of certainty equivalent to actual receipt. Future, contingent installments do not meet this standard and should not be deducted from the damages calculation.

5. Overruling Precedent:

The Supreme Court explicitly stated that its previous rulings (specifically citing the Showa 50 [1975] decision mentioned in the appeal and a Showa 52 [1977] decision) which allowed for the deduction of the present value of estimated future survivor pension benefits were overruled to the extent they conflicted with this new judgment.

6. Recalculation and Remand:

The Court found that the High Court had correctly limited the offset to benefits whose payment was certain but had erred slightly by only including amounts actually received by the close of oral arguments. According to the payment schedule stipulated in the MAA Act (Art. 75), payments made periodically cover preceding months. Therefore, the High Court should also have included installments that had accrued and become definitively payable by the closing date, even if the actual disbursement date was slightly later. Based on the payment dates and amounts, the Court determined that installments for May, June, and July 1988 (the months immediately preceding the close of arguments in July 1988) were definitively due and should also have been deducted, in addition to the amounts already received by X. The Court calculated this additional deductible amount and modified the High Court's damage award accordingly, reducing the final amount payable by Y. Since the main point of Y's appeal (challenging the limited offset) was essentially rejected under the new standard, the judgment effectively favored X on the core principle but required a minor adjustment in the final calculation. (Note: The main text of the judgment says "partially reversed and remanded," suggesting the High Court needed to finalize the calculation of the additional offset based on exact accrual dates relative to the closing of arguments, but the calculation seems mostly done by the Supreme Court itself).

The Dissenting Opinions

This Grand Bench decision was not unanimous and included significant dissenting opinions from five Justices, presenting alternative approaches:

- Dissent 1 (Justice Fujishima): Argued fundamentally that retirement pensions should not be treated as lost earnings in tort cases. They are life security payments, not direct reflections of earning capacity. Damages for wrongful death should be based on lost earning capacity, calculated using other methods (like wage statistics), not on the lost pension stream. If the lost retirement pension isn't the basis of the damage claim, the question of offsetting the survivor pension doesn't even arise in this context. This view would require a complete change in how damages are assessed in such cases and potentially lead to lower damage awards if earning capacity post-retirement is deemed low.

- Dissent 2 (Justices Sonobe, Sato, Kizaki): Agreed with Dissent 1 that retirement pensions are primarily life security, not lost earnings. Furthermore, they argued that survivor pensions, while also for life security, serve a distinct purpose aimed specifically at the survivor's needs after the primary earner's death. Because the purpose and beneficiary focus differ, they lack the necessary "homogeneity" (dōshitsusei) with the lost retirement pension for the son'eki sōsai principle to apply. Therefore, no survivor pension benefits (neither past nor future) should be deducted from the damages calculated based on the lost retirement pension (assuming, contrary to Dissent 1, that lost retirement pension is a valid head of damage). They argued this avoids unfairness to the survivor and aligns better with the distinct social security functions of each pension type.

- Dissent 3 (Justice Mimura): Argued in favor of upholding the prior Supreme Court precedent (the Showa 50 decision) that the majority overruled. This view holds that the entire present value of the survivor pension expected over the deceased's remaining life expectancy should be deducted. It acknowledges the uncertainty of future payments but argues this can be reasonably accounted for by using statistical data (life expectancy tables, remarriage rates for widows/widowers) to calculate the probable present value of the future benefit stream. This approach aims to prevent the perceived "double recovery" that occurs if the heir receives full damages for the lost retirement pension and the full survivor pension for the same future period. It criticizes the majority's "certainty" standard based on the trial end date as arbitrary and dependent on litigation speed, arguing it fails to achieve substantive fairness over the entire period.

Implications and Significance

The 1995 Grand Bench decision significantly altered the landscape of tort damages calculation in Japan where public pensions are involved:

- Overruling of Precedent: It explicitly overturned established case law that had allowed the deduction of estimated future survivor pension benefits.

- New Standard Based on Certainty: It established a new, stricter standard for offsetting future benefits under son'eki sōsai, limiting the deduction to benefits already paid or whose payment is definitively certain (accrued and unconditionally due) by the close of the final fact-finding trial.

- Increased Recovery for Plaintiffs: This change generally favors plaintiffs (surviving heirs) by reducing the amount deducted from their damages award compared to the previous method, leading to higher net compensation.

- Focus on Actual Compensation: The majority opinion reflects a strong emphasis on the compensatory purpose of tort law, ensuring that deductions are made only when the loss has been actually (or with near-certainty) compensated by the gain.

- Continuing Debate: The strong dissents highlight the ongoing theoretical debates surrounding the nature of pension benefits (lost earnings vs. life security), the principle of son'eki sōsai, and how to fairly account for future uncertainties in damage calculations. The majority's focus on certainty contrasts sharply with approaches favoring statistical probability or different underlying damage theories.

- Practical Application: The ruling requires careful attention to the timing of benefit accrual and payment dates relative to the conclusion of court proceedings when calculating damages in these types of cases.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench judgment of March 24, 1995, marked a pivotal change in Japanese tort law concerning the offsetting of survivor pension benefits against damages for lost retirement pensions. By overruling prior precedent and establishing a stricter standard based on payment certainty, the Court limited the scope of son'eki sōsai deductions to survivor benefits already received or definitively due by the close of the final fact-finding trial. This decision prioritizes the principle that offsets should only occur when a loss has been actually or near-certainly compensated, even if it means departing from previous methods aimed at preventing potential future overlaps between damages and benefits. The ruling continues to influence how damages are calculated in wrongful death cases involving social security pensions in Japan.

- When a Lie Becomes a Crime: Japan's Landmark Case on Lying for an Arrested Friend

- The Scapegoat Gambit: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Aiding an Arrested Criminal's Escape

- Memory vs. Truth: How Japan's High Court Defined Perjury Over a Century Ago

- Judgments of the Supreme Court of Japan – English Database

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare – Public Pension Overview