Off-Site Work and "Deemed Hours": Japan's Supreme Court Clarifies "Difficult to Calculate" for Tour Guides (January 24, 2014)

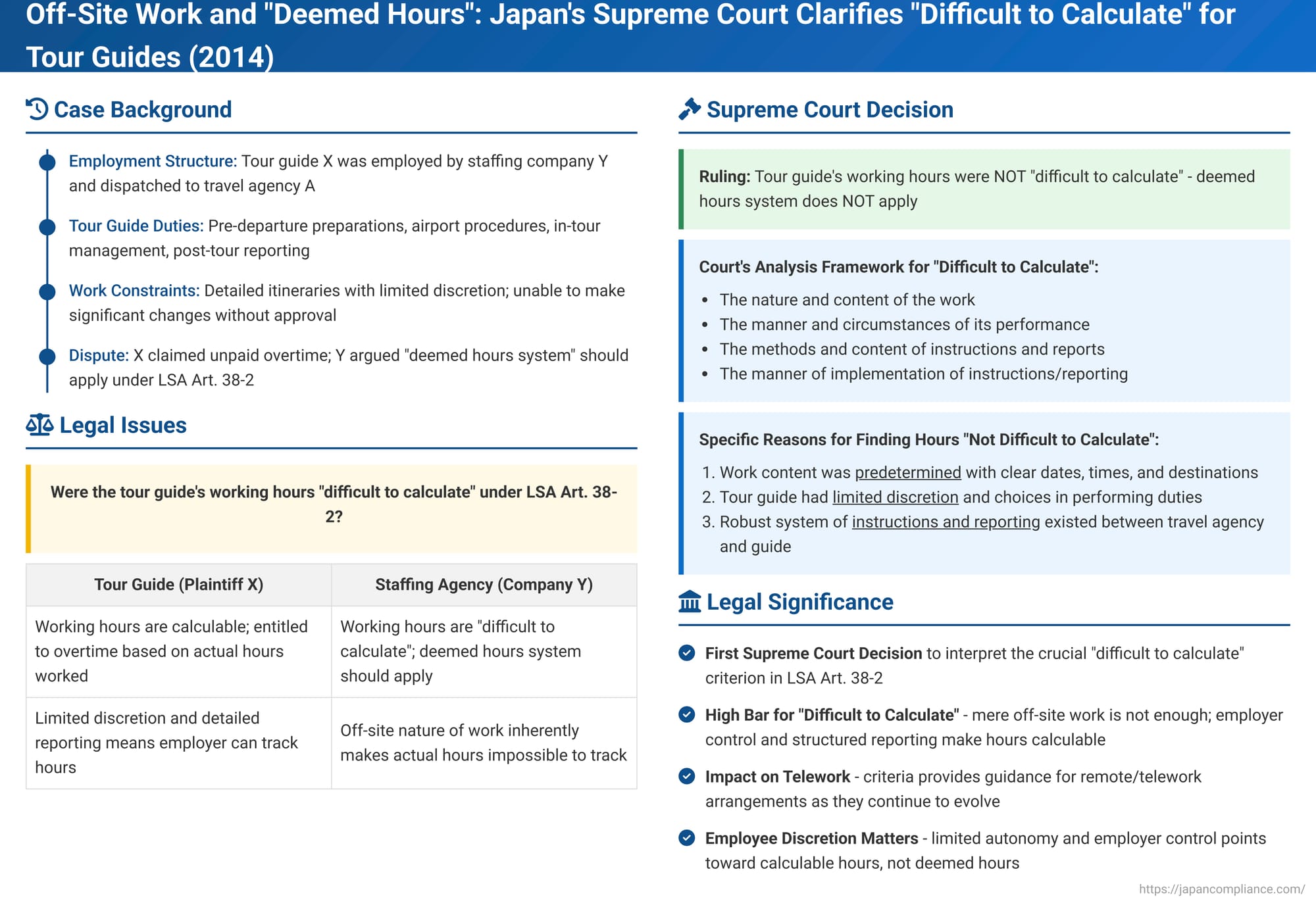

On January 24, 2014, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered an important judgment in a case concerning overtime pay for a dispatched tour guide. This case, often referred to by commentators as the "Hankyu Travel Support (No. 2) Case," provides crucial clarification on the application of Japan's "deemed working hours system for work outside the workplace" (事業場外労働みなし制 - jigyōjōgai rōdō minashi sei) under Article 38-2, Paragraph 1 of the Labor Standards Act (LSA). Specifically, it delves into the conditions under which an employee's working hours performed off-site are considered "difficult to calculate" (労働時間を算定し難いとき - rōdō jikan o santei shi gatai toki), a key prerequisite for applying this system.

The Life of a Dispatched Tour Guide: Structure, Duties, and Constraints

The defendant, Company Y, was a general temporary staffing agency. It dispatched registered tour guides to client companies, such as Company A (a travel agency, not a party to the suit but the dispatch destination), for specific tours under individual fixed-term employment contracts with the guides. The plaintiff, X, was a tour guide registered with Company Y and was dispatched to Company A to conduct overseas tours.

Plaintiff X's duties for each tour generally followed a structured pattern:

- Pre-Departure Preparations: Approximately two days before a tour's departure, X would visit Company Y's office. There, X received tour materials like brochures, final itineraries, and an "itinerary" document (a detailed schedule for the tour guide, often including local arrangements). X would also have meetings with the staff of the company responsible for local arrangements in the destination country.

- Departure Day Activities: On the day of departure, X was required to arrive at the airport at least one hour before the scheduled assembly time for tour participants. X's responsibilities included receiving airline tickets and other necessary documents, meeting and registering tour participants at the designated airport location, and guiding them through departure formalities such as check-in, immigration, and boarding procedures. During the flight to the destination, X also provided information and assistance to participants, particularly after boarding and before arrival.

- Arrival and In-Tour Management (Overseas): Upon arrival at the overseas destination, X was responsible for tasks such as assisting with hotel check-in procedures and providing guidance to the tour participants. Throughout the tour, X's core duty was to manage the itinerary. This typically involved being engaged from breakfast time, through sightseeing activities, until the conclusion of dinner each day, ensuring the tour proceeded according to the pre-established schedule.

- Return Journey and Post-Tour Reporting: On the day of return to Japan, X's duties included managing departure procedures from the hotel through to boarding the aircraft, and providing necessary information during the return flight. After arriving back in Japan, X would see the tour participants through customs at the airport, marking the end of the on-tour duties. Within three days of returning, X was required to visit Company Y's office to submit a report. Additionally, X had to go to the offices of Company A (the travel agency) to submit a detailed tour daily report (添乗日報 - tenjō nippō) and any questionnaires collected from the tour participants.

A critical aspect of the work involved adherence to the planned itinerary:

- The travel agency, Company A, had contractual obligations with tour participants based on the tour brochures and final itineraries. Unilaterally changing key elements like travel dates, destinations, transportation methods, or accommodation without participant consent would generally breach the travel agency's standard terms and conditions (旅行業約款 - ryokōgyō yakkan) related to itinerary guarantees. Such breaches could necessitate Company A paying compensation to the affected participants. Consequently, tour guides like X were under a strict obligation to manage the tour in a way that prevented such unauthorized changes.

- However, the system allowed for some flexibility. If deemed unavoidable for the safe and smooth execution of the tour, minor itinerary changes could be made, sometimes at the tour guide's own discretion, within necessary minimal limits. But for more significant alterations—such as changes to destinations or accommodations that could trigger contractual issues like compensation payments or lead to participant complaints—tour guides were explicitly required to report the situation to Company A's designated sales representative and await instructions.

The Legal Dispute: Unpaid Overtime vs. "Deemed Hours"

Plaintiff X initiated legal action against Company Y, asserting that during the course of conducting these overseas tours, X had worked hours exceeding the statutory limits of 8 hours per day and 40 hours per week. Despite this, X claimed not to have received the corresponding overtime premium wages and sought their payment under Article 37 of the LSA. Company Y, in its defense, argued that the nature of the tour guide work fell under the LSA's "deemed working hours system for work outside the workplace," meaning X should be deemed to have worked the prescribed standard hours, thus negating the overtime claim.

The case saw differing outcomes in the lower courts:

- The Tokyo District Court (First Instance) found that the tour guide work was indeed a situation where calculating actual working hours was difficult. It therefore applied the deemed working hours system. However, the court determined that the "normally necessary" hours for performing such duties were 11 hours per day. Consequently, any hours worked beyond the standard 8-hour day (up to this 11-hour deemed figure) were considered unpaid overtime, and the court largely upheld X's claim for these amounts.

- The Tokyo High Court (Appeal) took a different view regarding the applicability of the deemed hours system. It concluded that the working hours of the tour guides were calculable and, therefore, denied the application of the deemed working hours system under LSA Article 38-2. Despite this, it still partially upheld X's claim, likely based on an assessment of actual hours worked once the deemed system was ruled out. Company Y appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

It's noteworthy that this "No. 2" case was one of three similar parallel cases involving dispatched tour guides for Company A's tours. The first instance courts in Case No. 1 and Case No. 3 (and this No. 2 case) had conflicting views on applying the deemed hours system. However, all three High Court appeal judgments denied the application of the system. Ultimately, only this No. 2 case received a substantive judgment from the Supreme Court on the matter; the appeals in the other two cases were either dismissed or not accepted for hearing.

The Supreme Court's Verdict: Working Hours Were Not "Difficult to Calculate"

The Supreme Court dismissed Company Y's appeal, thereby upholding the Tokyo High Court's decision that the deemed working hours system was not applicable to Plaintiff X's tour guide work. The Court's reasoning focused on whether the work met the LSA Article 38-2 criterion of being "difficult to calculate working hours."

The Supreme Court found:

- Predetermined Work Content and Limited Discretion: "The tour guide work in this case, because the tour itinerary is set with clear dates, times, and destinations, means the content of the work is specifically determined in advance, and the scope of matters the tour guide can decide on their own, and the range of choices in those decisions, are limited." This indicates that the highly structured nature of the tours significantly constrained the tour guide's autonomy over their work schedule and tasks.

- System of Instructions and Reporting: "Regarding the tour guide work, Company A [the client travel agency] specifically instructs the tour guide to manage the itinerary according to the pre-determined schedule. If a situation arises during the tour requiring a significant change to the planned itinerary, individual instructions are to be given at that time. After the tour ends, Company A receives detailed reports on the work performance through a tour daily report whose accuracy can be verified." This pointed to a robust system of ongoing direction and post-hoc verification by the client company.

- Conclusion on Calculability: Based on a comprehensive consideration of "the nature and content of the work, the manner and circumstances of its performance, the methods and content of instructions and reports between Company A and the tour guide, and the manner and circumstances of their implementation," the Supreme Court concluded that "it is difficult to recognize that specifically grasping the working situation of the tour guides engaged in this work was difficult." Therefore, the situation did "not fall under 'when it is difficult to calculate working hours' as stipulated in Article 38-2, Paragraph 1 of the Labor Standards Act."

In essence, the Supreme Court determined that the combination of highly detailed, pre-set itineraries, the requirement for guides to seek instructions for significant changes, and the detailed post-tour reporting mechanisms meant that Company A (and by extension, Company Y as the dispatching employer) had sufficient means to ascertain the tour guides' working hours.

Unpacking "Difficult to Calculate Working Hours"

This Supreme Court judgment was the first to provide authoritative guidance on interpreting the "difficult to calculate working hours" criterion within LSA Article 38-2.

- LSA Article 38-2 Explained: This provision creates an exception to the standard methods of calculating working time. It applies when employees perform all or part of their duties outside the employer's direct physical premises, and it is genuinely "difficult to calculate their working hours". If the system applies, employees are generally deemed to have worked their "prescribed working hours" (the standard hours set in their contract or work rules). However, if the tasks "normally require" work beyond these prescribed hours, they are deemed to have worked the hours "normally necessary" for completing those tasks. If a labor-management agreement specifies these "normally necessary" hours, that agreed time is used.

- The Supreme Court's Comprehensive Assessment Criteria: Prior to this ruling, the interpretation of "difficult to calculate" was largely guided by administrative circulars from the Ministry of Labour (now MHLW). These circulars typically listed scenarios where hours were not considered difficult to calculate, such as:

- When employees work in a group off-site, and one member is tasked with managing work time.

- When employees working off-site receive ongoing instructions from their employer via mobile phone or other communication devices.

- When employees receive specific instructions at the workplace (e.g., places to visit, return time), perform their duties accordingly outside, and then return to the workplace.

This Supreme Court decision established a more holistic analytical framework. It requires considering:

- The "nature and content of the work" itself.

- The "manner and circumstances of its performance."

- The "methods and content of instructions and reports" between the employer (or client company, in a dispatch context) and the employee.

- The "manner and circumstances of the implementation" of these instructions and reports.

- Role of Employee Discretion and Employer Control: In applying these criteria to the tour guide case, the Supreme Court first noted the limited discretion of the tour guides due to the detailed, pre-set itineraries. This lack of autonomy was a significant factor. The Court then analyzed the system of instructions (detailed itineraries, manuals, requirement to seek directions for changes) and reporting (comprehensive daily tour reports). This demonstrated that the client company, Company A, maintained a significant degree of specific operational direction and had mechanisms for detailed post-performance oversight, making it feasible to grasp the working hours. The commentary suggests this case might have fit within the pre-existing administrative circular exceptions, but the Court's explicit framework provides a broader, more principled basis for future assessments. The limited discretion of the worker likely reinforced the finding that hours were not difficult for the employer to ascertain. In contrast, cases where employees have high levels of discretion and minimal reporting obligations (e.g., some sales positions, as seen in the Nakku Jiken mentioned in the commentary) might still qualify for the deemed hours system.

Broader Implications, Including for Telework

The principles from this Supreme Court judgment extend beyond tour guides to various forms of off-site work, including the increasingly prevalent practice of telework.

- Telework and Deemed Hours: The MHLW has issued guidelines (last revised March 25, 2021, as per the commentary) concerning telework and the deemed hours system. These guidelines suggest that the system can apply to telework if certain conditions are met:

- Information and communication technology (ICT) devices are not, by employer instruction, required to be in a state of constant communication.

- The work is not performed based on specific, ad-hoc instructions from the employer during the workday.

The commentary notes that this guidance affirmatively outlines when the deemed system might be applicable to telework, a slight shift from older circulars that focused on when it doesn't apply.

- Ongoing Challenges: However, the practical application remains complex. Terms like "specific instructions" can be ambiguous given the diverse and evolving nature of telework arrangements. As ICT further transforms how off-site work is managed and monitored, the courts will continue to refine the application of the Supreme Court's criteria.

- Importance of Actual Hours and Health Management: Even if the deemed hours system is legitimately applied, the "deemed" hours themselves must be appropriate for the work normally required. The MHLW guidelines encourage employers and employees to regularly review and adjust these deemed hours based on actual work realities. Furthermore, employers retain their obligations under the Industrial Safety and Health Act to monitor the working hour situations of their employees and to provide access to occupational physician interviews for those working long hours, irrespective of whether a deemed hours system is in place. The prevention of overwork and the safeguarding of employee health remain paramount.

Conclusion: "Difficult to Calculate" Sets a High Bar

The Supreme Court's decision in the Travel Support Company Y (No. 2) case establishes that the "difficult to calculate working hours" criterion for applying the LSA Article 38-2 deemed hours system is not easily met merely by virtue of work being performed outside the employer's physical premises. Where work content is largely predetermined, employee discretion is limited, and robust systems for instruction and reporting exist, it is unlikely that working hours will be considered genuinely difficult for the employer to ascertain. This ruling emphasizes a substantive assessment of the employer's ability to manage and track working hours, regardless of the work's location.