Off-Duty Conduct, On-the-Hook? Japan's Supreme Court on Enterprise Order and Employee Discipline (September 8, 1983)

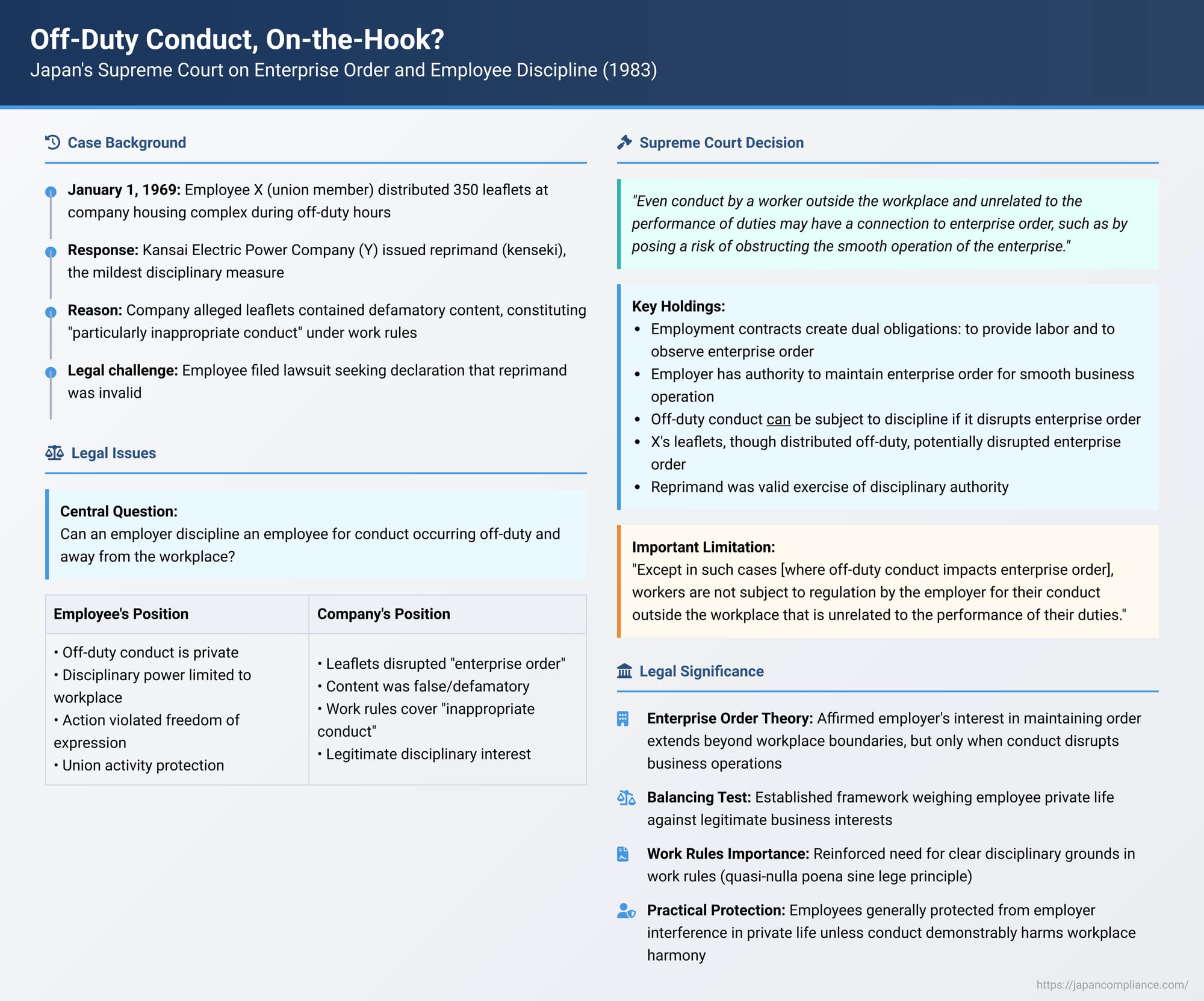

On September 8, 1983, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in a case commonly known as the "Kansai Electric Power Case" (関西電力事件). This ruling addressed the extent of an employer's authority to discipline an employee for conduct undertaken outside of working hours and away from the workplace, specifically focusing on activities deemed to disrupt or potentially harm what is known in Japanese labor law as "enterprise order" (企業秩序 - kigyō chitsujo). The case provides crucial insights into the balance between an employee's private life and an employer's legitimate interest in maintaining a well-functioning organization.

The Leaflet Distribution and the Company's Response

The plaintiff, X, was an employee of Company Y, an electric power company, and also a member of the A Labor Union, an internal union of Company Y's employees. Believing that Company Y was exerting increasing pressure on union members and that there was a need to strengthen union solidarity to counter this, X took action. In the early morning hours of January 1, 1969 – a day off and outside of working hours – X distributed approximately 350 leaflets at an employee housing complex owned by Company Y.

Company Y management viewed the content of these leaflets as defamatory and slanderous towards the company. Consequently, Company Y imposed a disciplinary measure on X in the form of a reprimand (譴責 - kenseki), which was the mildest form of disciplinary action stipulated in its work rules. The company asserted that X's act of creating and distributing the leaflets constituted "other particularly inappropriate conduct" (その他特に不都合な行為があったとき), a disciplinary cause listed under Article 78, Item 5 of its employment regulations.

Dissatisfied with this disciplinary action, X filed a lawsuit seeking a declaration that the reprimand was invalid.

The Lower Courts' Diverging Views

- Kobe District Court, Amagasaki Branch (First Instance): The District Court ruled in favor of Plaintiff X. It found that X's act of distributing the leaflets did not amount to "particularly inappropriate conduct" warranting disciplinary action under the company's work rules.

- Osaka High Court (Appeal): The High Court reversed the District Court's decision. It determined that the majority of the content in the leaflets distributed by X was not based on factual information, or that it significantly exaggerated and distorted facts in a way that slandered and defamed Company Y. The High Court concluded that this conduct had the effect, or at least the potential, of fostering distrust among employees towards the company and thereby disrupting enterprise order. Given these findings, the High Court held that the company's decision to issue a reprimand was a valid exercise of its disciplinary authority and did not exceed the bounds of discretion afforded to it.

Plaintiff X appealed this adverse High Court ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Stance: Protecting Enterprise Order, Even Off-Duty

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision that the reprimand was valid. The Supreme Court's judgment elaborated on the employer's right to maintain enterprise order and the circumstances under which off-duty conduct could legitimately be subject to disciplinary action.

- The Dual Obligations of an Employee and Employer's Right to Discipline: The Court began by affirming a foundational principle: "By entering into an employment contract and being employed, a worker bears an obligation to provide labor to the employer and, at the same time, an obligation to observe enterprise order. The employer, to broadly maintain enterprise order and thereby ensure the smooth operation of the enterprise, can impose discipline, a type of sanction, on an employed worker for conduct that violates enterprise order".

- Extension of Enterprise Order to Off-Duty, Off-Premises Conduct: The Court then addressed the core issue of regulating private activities: "While this enterprise order can normally be maintained by regulating workers' conduct within the workplace or related to the performance of their duties, even conduct by a worker outside the workplace and unrelated to the performance of duties may have a connection to enterprise order, such as by posing a risk of obstructing the smooth operation of the enterprise".

Based on this, the Court stated: "Therefore, for the maintenance and security of enterprise order, it is permissible for the employer to also make such [off-duty, non-work-related] conduct a subject of regulation and to impose discipline on a worker for such reasons (referencing a previous Supreme Court judgment from February 28, Showa 49 (1974))". - Limits on Employer Regulation of Private Life: However, this power is not unlimited. The Court also clarified: "Except in such cases [where off-duty conduct impacts enterprise order], it is reasonable to interpret that workers are not subject to regulation by the employer for their conduct outside the workplace that is unrelated to the performance of their duties".

- Application to X's Case: The Supreme Court found the High Court's factual determination—that the leaflets were largely baseless or distorted facts intended to criticize and slander Company Y, and that their distribution risked disrupting enterprise order by creating employee distrust—to be supported by the evidence presented. The Supreme Court saw no error in this assessment.

It concluded: "Based on the High Court's said findings and determination, and in light of what has been stated above, X's distribution of the said leaflets, although conducted outside working hours, outside the workplace (at Company Y's employee housing), and unrelated to the performance of duties, can be construed as falling under the aforementioned disciplinary cause in the work rules".

Therefore, "Imposing a reprimand, as a form of discipline, on X for this reason cannot be recognized as exceeding the scope of discretionary authority granted to the disciplinary authority. The High Court's judgment, which is to the same effect, is correct". - Constitutional and Union Activity Arguments: The Supreme Court also dismissed X's arguments that the disciplinary action violated constitutional rights (such as freedom of expression) or constituted interference with legitimate labor union activities. It held that even if the leaflet distribution had an expressive component, disciplining X for it in this context did not violate public order and good morals, nor could X's specific actions be deemed a legitimate act of a labor union.

Understanding "Enterprise Order" and the Basis of Disciplinary Power

This judgment is a key illustration of the "enterprise order theory" (企業秩序論 - kigyō chitsujo ron) prevalent in Japanese labor law.

- The Concept of Enterprise Order: Japanese case law generally recognizes that employers have a legitimate interest in establishing and maintaining order within their enterprise to ensure its smooth and efficient operation. Employees, by virtue of their employment contract, are considered to have an ancillary obligation to respect this enterprise order.

- Legal Basis for Disciplinary Power: The precise legal source of an employer's disciplinary power has been a subject of academic debate in Japan, as no single statute explicitly grants it.

- The "Inherent Rights Theory" (固有権説 - koyūken setsu) suggests that employers possess an inherent right, as part of their managerial authority, to discipline employees to maintain order necessary for business operations, even without explicit provisions in work rules.

- The "Contract Theory" (契約説 - keiyaku setsu), which is now the prevailing academic view, argues that in an employment contract between notionally equal parties, disciplinary power is not automatically assumed. It requires a specific contractual basis, which is typically found in the company's work rules (就業規則 - shūgyō kisoku). Under this theory, if the work rules (which must themselves be reasonable to be binding on employees, as per Article 7 of the Labor Contract Act) clearly stipulate the grounds for disciplinary action and the types of sanctions, then the employer can impose such discipline based on these contractual provisions.

- The Supreme Court's line of reasoning in cases like this one, emphasizing the employer's need to maintain enterprise order for the business's function, has sometimes been seen as aligning more closely with an inherent rights perspective, or at least a strong recognition of managerial prerogative in this area. However, the Court has also, in other cases (e.g., the Fuji Heavy Industries Case, 1977), stated that employees are not subject to the "general control" of the employer outside of work, and in the Nestle Japan (Disciplinary Dismissal) Case (2006), it noted that disciplinary power is exercised "as an employer's authority based on the employment relationship from the perspective of maintaining enterprise order".

- A balanced interpretation, as suggested by the commentary, is that while employers may have a recognized authority to establish and protect enterprise order, the exercise of disciplinary power is linked to breaches of the employee's duty to observe this order, which is an ancillary obligation arising from the principle of good faith inherent in the employment contract.

- Crucial Limitation on Disciplining Off-Duty Conduct: The most critical takeaway from the Kansai Electric Power case and related jurisprudence is that for an employer to legitimately discipline an employee for conduct occurring outside of working hours and away from the workplace, that conduct must have a demonstrable, tangible link to, or a reasonably foreseeable adverse impact on, the "smooth operation of the enterprise" or its internal order. General disapproval of an employee's private activities is not sufficient. There must be an objective basis for concluding that the conduct affects the employer's legitimate business interests or workplace harmony.

The Indispensable Role of Work Rules

The commentary also underscores the importance of work rules in the context of disciplinary actions.

- Principle of Legality in Discipline: Given that disciplinary sanctions are quasi-penal in nature, imposing penalties on employees, there's a strong legal consensus that principles analogous to nulla poena sine lege (no punishment without a pre-existing law) should apply.

- Requirement for Pre-Specification: Reflecting this, the Supreme Court in other cases (e.g., the Fuji Kōsan Case, 2003) has clearly stated that for an employer to validly discipline an employee, the types of disciplinary measures and the specific grounds (offenses) for such measures must be explicitly stipulated in the work rules beforehand.

- Modern Judicial Practice: In contemporary practice, lower courts routinely assess the validity and appropriateness of disciplinary actions by closely examining whether the employee's conduct falls within the pre-defined disciplinary causes in the applicable work rules and whether the sanction imposed is reasonable and proportionate.

While the foundational legal theory for disciplinary power (inherent right vs. contract) continues to be debated academically, the practical reality is that most disciplinary actions are, and must be, grounded in and justified by clear provisions within the company's work rules. However, understanding the theoretical underpinnings remains important for addressing fringe cases, such as disciplinary actions by employers not legally required to formulate work rules, or for critically evaluating the outer limits of disciplinary power, especially concerning severe sanctions like disciplinary dismissal.

Conclusion: A Conditional Extension of Employer Authority

The Supreme Court's judgment in the Electric Power Company Y (Kansai Electric Power) case affirms that an employer's authority to maintain enterprise order and impose discipline can, under specific circumstances, extend to an employee's conduct outside of working hours and off company premises. However, this extension is strictly conditional: the off-duty conduct must have a clear, adverse connection to the employer's legitimate business interests or the harmonious operation of the enterprise. The ruling reinforces the principle that an employee's private life is generally beyond the scope of employer regulation, unless their actions in that private sphere demonstrably and negatively impact the workplace or the company's ability to function smoothly. The case serves as a reminder of the careful balance that must be struck between respecting employee freedoms and protecting essential enterprise order.