Not My Child, Not My Bill? Japan's Supreme Court on Child Support, Concealed Paternity, and 'Abuse of Rights'

Date of Judgment: March 18, 2011

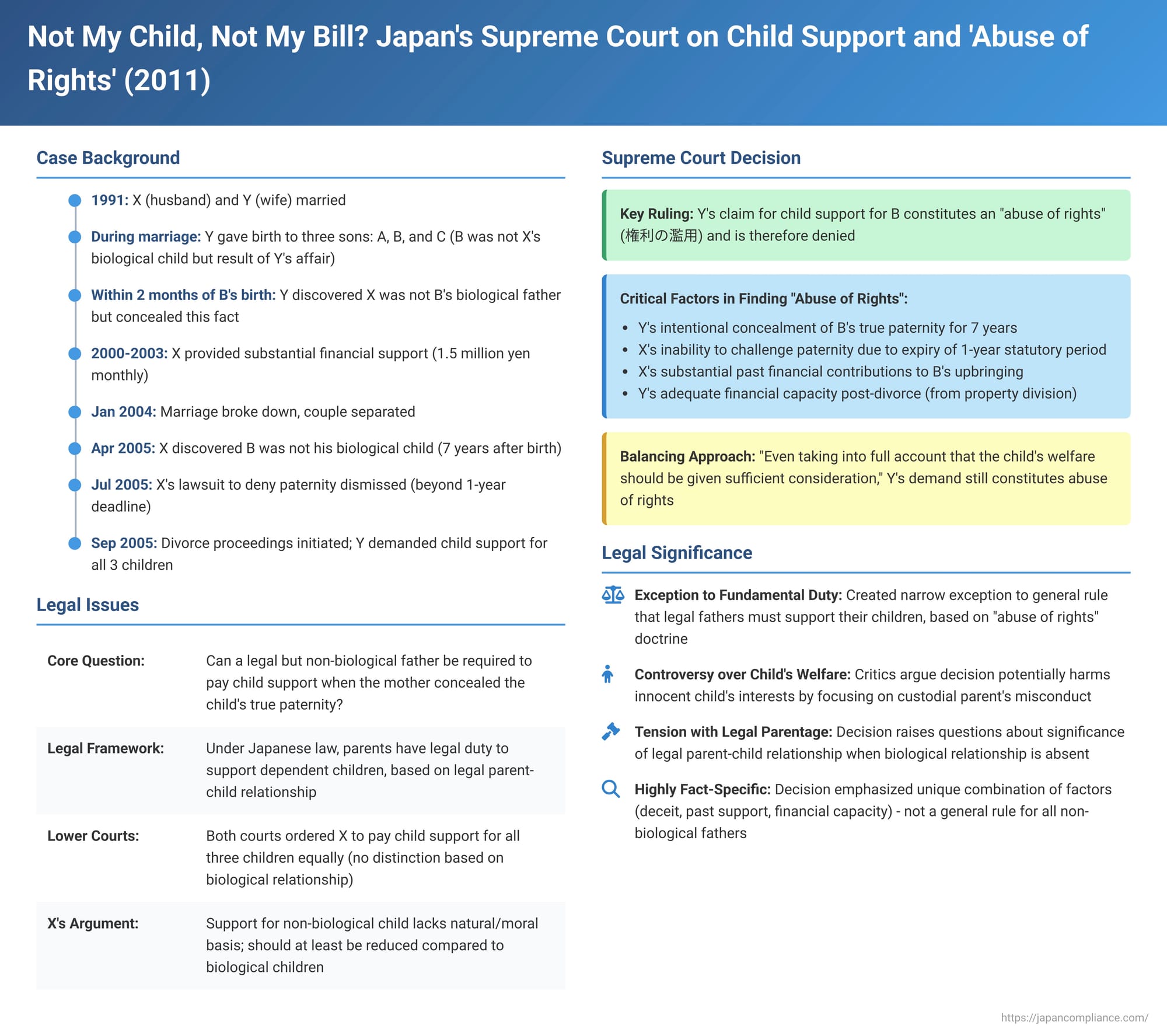

The legal obligation of parents to financially support their children is a cornerstone of family law worldwide. In Japan, this duty generally extends from legal parentage, often established through presumptions tied to marriage. But what happens when a complex and distressing situation arises: a husband is the legal father of a child who is not biologically his, he was prevented from challenging this legal status in time due to the wife's concealment of the truth, and then, upon divorce, the wife seeks child support from him for that child? The Supreme Court of Japan confronted this thorny issue in a notable decision on March 18, 2011 (Heisei 21 (Ju) No. 332), ultimately denying the wife's claim for support for the non-biological child on the grounds that her demand constituted an "abuse of rights."

The Facts: A Marriage, Three Children, and a Long-Hidden Truth

The case involved a husband, X, and his wife, Y, who had married in Heisei 3 (1991). During their marriage, Y gave birth to three sons: A, B, and C, all of whom were legally presumed to be X's children. However, the second son, B, was biologically the child of another man with whom Y had an affair. According to the facts established by the court, Y became aware that X was not B's biological father within approximately two months of B's birth but chose not to disclose this crucial information to X.

The marital relationship between X and Y was described as not always harmonious, with instances of Y perpetrating violence against X. From around 1997, X entrusted Y with the family's finances, allowing her to manage living expenses from his bank accounts. Even after transitioning to giving Y a fixed monthly sum for living expenses around 1999, X, in response to Y's requests, provided a substantial amount—approximately 1.5 million yen per month—for family living expenses for about four years, from early 2000 to the end of 2003. These funds naturally covered the upbringing of all three children, including B.

The marriage eventually broke down around the end of January 2004, partly attributed to X having an affair with another woman. Following their separation, a family court umpire decision ordered X to pay Y 550,000 yen per month as marital expenses (support payments during separation), a decision which became final and binding.

It was not until April 2005, roughly seven years after B's birth, that X first discovered that B was not his biological child. This discovery was reportedly prompted by a discrepancy in blood types. In July 2005, X initiated legal proceedings to obtain a judicial confirmation of the non-existence of a parent-child relationship with B. However, this lawsuit was dismissed, and the dismissal became legally final. Under Japanese law (Civil Code Article 777), an action by a husband to deny the paternity of a child presumed legitimate must be filed within one year of his knowledge of the child's birth. By the time X learned the truth, this statutory window had long since closed, leaving him with no legal recourse to sever his legal parental ties to B.

The Divorce Proceedings and the Dispute Over Child B's Support

In September 2005, X filed for divorce from Y and also sought solatium (damages for emotional distress). Y, in turn, filed a counterclaim for divorce and other remedies. Relevant to this Supreme Court decision, Y sought an order for X to pay child support (custodial expenses, or yōikuhi) for all three children—A, B, and C—at a rate of 200,000 yen per month per child until each child reached adulthood. She also requested property division and a splitting of pension benefits.

The first instance court (Tokyo Family Court) and the appellate court (Tokyo High Court) both granted the divorce and designated Y as the custodial parent for all three children. They also ordered X to pay child support for A, B, and C in equal amounts (the first instance ordered 160,000 yen per month per child, which the appellate court revised to 140,000 yen per month per child).

X specifically contested his obligation to support child B. He argued that being forced to pay child support for a child with whom he shared no biological link lacked a natural and moral basis, and that, at the very least, he should not be required to pay the same amount for B as for his biological children, A and C. The appellate court rejected this argument, stating that "it is difficult to recognize a difference in the obligation to pay child-rearing expenses based on the presence or absence of a biological blood relationship with a child who has a legal parent-child relationship". The courts also ordered a division of property, which resulted in X being required to transfer assets worth approximately 12.7 million yen to Y. Additionally, the appellate court ordered X to pay Y 1 million yen as solatium for his role in the divorce, and, significantly, ordered Y to pay X 1 million yen as solatium for the tort of having deprived X of the opportunity to legally contest B's paternity.

X then appealed to the Supreme Court, specifically challenging the part of the appellate decision that ordered him to pay post-divorce child support for B.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: Wife's Claim for B's Support Denied as an "Abuse of Rights"

In a significant ruling, the Supreme Court partially overturned the lower court's decision. It specifically reversed the order requiring X to pay child support for B, quashed the first instance judgment concerning B's support, and dismissed Y's claim against X for B's custodial expenses. The orders for X to support his biological children, A and C, were not disturbed.

The Supreme Court's core finding was that Y's demand for X to pay post-divorce child support for B, under the unique and compelling circumstances of this case, constituted an "abuse of rights" (権利の濫用 - kenri no ran'yō).

Key Factors Leading to the "Abuse of Rights" Conclusion:

The Court meticulously laid out the factors that, when considered comprehensively, led to this exceptional conclusion:

- Y's Concealment and Deprivation of X's Legal Rights: The Court emphasized that Y, despite being married to X, had an affair with another man which resulted in B's birth. Critically, Y knew within approximately two months of B's birth that X was not the biological father but intentionally concealed this fact from X. X only learned the truth about seven years later. This prolonged concealment directly resulted in X being unable to file an action to deny paternity of a legitimate child within the strict one-year statutory period prescribed by Civil Code Article 777. His subsequent attempt to seek a judicial declaration of non-paternity was consequently dismissed. As a result, X was left with no legal means to sever his legal parental relationship with B, a relationship founded on a falsehood actively maintained by Y.

- X's Substantial Past Financial Contributions to B's Upbringing: The Court noted that X had already borne a significant financial burden for B's upbringing over many years. This included the period when he entrusted Y with managing the family finances from his bank accounts, the subsequent four years prior to the marital breakdown when he provided Y with substantial monthly living expenses (around 1.5 million yen per month), which covered B's costs as part of the family, and the ongoing court-ordered marital expense payments of 550,000 yen per month he made to Y after their separation. The Court stated that, given Y's actions that locked X into legal paternity, forcing X to also bear post-divorce child support specifically for B would impose an "excessive burden" (過大な負担 - kadai na futan) on him.

- Y's Financial Capacity Post-Divorce: The Court pointed out that Y was set to receive a "considerably large amount" in property division from X as part of the divorce settlement. There was no evidence presented to suggest that Y would be financially incapable of covering B's custodial expenses on her own after the divorce.

- Child B's Welfare Not Compromised: Taking into account Y's anticipated financial situation due to the property division, the Court concluded that having Y solely bear B's post-divorce custodial expenses would not be contrary to the child's welfare.

Balancing Child Welfare and Fairness to the Deceived Parent:

The Supreme Court explicitly stated that "even taking into full account that the child's welfare should be given sufficient consideration when determining contribution to custodial expenses," Y's demand for X to contribute to B's support nonetheless constituted an abuse of rights. This indicates a careful balancing act, where the normally paramount consideration of child welfare was weighed against the extreme prejudice suffered by X due to Y's deceit.

The Legal Basis of Child Support in Japan and Critiques of the Decision

In Japan, parents have a strong legal duty to support their dependent children (扶養義務 - fuyō gimu). After a divorce, this obligation is typically fulfilled through payments for "custodial expenses" or "child-rearing expenses" (養育費 - yōikuhi), usually paid by the non-custodial parent to the custodial parent. This is often arranged by agreement or, if disputed, determined by the family court, typically under Civil Code Article 766, which addresses matters concerning child custody upon divorce, including the sharing of expenses. This parental obligation is generally understood as being for the child's benefit, flowing from the legal parent-child relationship.

The Supreme Court's 2011 decision to deny child support for B based on an "abuse of rights" by Y has generated considerable discussion and criticism among legal scholars in Japan, as noted in the legal commentary accompanying the case.

- Focus on Custodial Parent's Conduct, Potentially Harming the Child: A primary critique is that child support is fundamentally intended for the child's benefit and welfare. Using the misconduct of the custodial parent (Y's concealment) as the primary reason to deny the child (B) financial support from one of their legally recognized parents (X) seems to penalize the child for the parent's actions. The argument is that the child's right to support should be independent of the custodial parent's behavior towards the other parent.

- Undermining the Significance of Legal Parentage: Japanese law, through its system of presuming legitimacy and the strict, time-limited procedures for denying paternity, deliberately creates legal parent-child relationships that are difficult to overturn. This is done to ensure stability and certainty for the child. Critics argue that this Supreme Court decision, by relieving a legal father of his support obligation based on the lack of a biological link (coupled with the mother's conduct), could be seen as weakening the significance and consequences of that established legal parental status. The Supreme Court itself, in other contexts (such as the 2015 decision on the women's remarriage waiting period, which also concerned paternity presumptions), has emphasized the importance of the legal parent-child status for the child's stability.

- Alternative Remedies for the Deceived Husband: It has been questioned whether X's legitimate grievance against Y for her deceit could have been more appropriately addressed through other legal avenues, rather than by denying child support for B. For example, X could have sought (and indeed was awarded by the lower court) separate tort damages from Y for the emotional distress and the loss of his opportunity to deny paternity. Adjustments could also potentially have been made in the property division to account for Y's conduct. The argument is that these remedies directly target the wrongdoing parent, whereas denying child support indirectly affects the child.

- What if Child B Sued Directly for Support? The legal commentary raises an interesting point: if child B, through a legal representative (even Y, acting in her capacity as B's legal representative for this specific purpose), were to directly sue X for support under Civil Code Article 877 (the general provision for family support obligations), that claim might well be upheld. This is because the "abuse of rights" finding in the 2011 Supreme Court case was specific to Y's claim against X within the context of their divorce proceedings and Y's own conduct. A direct claim by the child might be assessed differently, focusing more squarely on the child's needs and X's status as legal father.

Conclusion: A Highly Fact-Specific Exception to a Fundamental Duty

The Supreme Court of Japan's March 2011 decision is a nuanced and highly fact-specific ruling. It carves out a narrow exception, based on the doctrine of "abuse of rights," to the otherwise fundamental rule that a legal father is obligated to contribute to his child's financial support. The unique and egregious combination of factors present in this case—the wife's deliberate and prolonged concealment of her child's true paternity, the husband's consequent irreversible status as legal father, his already substantial past financial contributions to the child's upbringing, and the wife's financial ability to support the child post-divorce without the husband's further contribution—were all deemed critical by the Court in reaching its conclusion.

While the decision aims to achieve a measure of fairness for a husband who was significantly wronged, it has also ignited a robust debate among legal experts about its potential impact on the principles of child support that flow from legal parentage and the paramount consideration of the child's welfare in family law matters. The case underscores the profound legal and ethical challenges that arise when the legal fictions of parentage, designed for stability, collide with biological realities and deeply personal betrayals.