Not Just the Product, But the Source: Japan's Supreme Court on Goods Similarity (Tachibana Masamune Case)

Judgment Date: June 27, 1961

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Case Number: Showa 33 (O) No. 1104 (Action for Rescission of a Trial Decision)

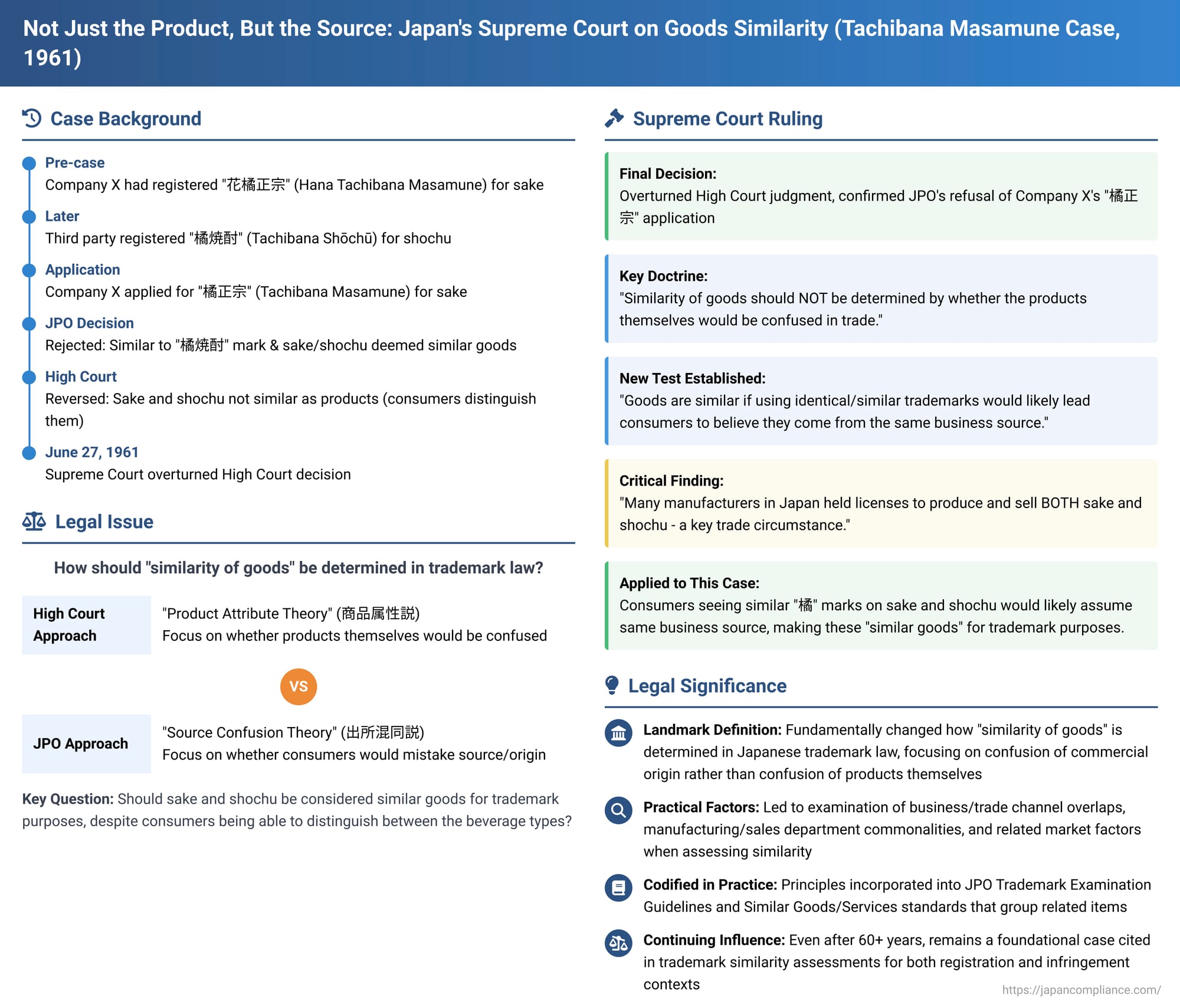

The "Tachibana Masamune" (橘正宗) case, decided by the Japanese Supreme Court in 1961, is a foundational judgment that fundamentally shaped the criteria for determining the "similarity of goods" (商品の類否 - shōhin no ruihi) in Japanese trademark law. The Court decisively moved away from a test based on whether consumers would confuse the products themselves, establishing instead that goods are considered similar if the use of identical or similar trademarks on them would likely lead consumers to misidentify their commercial source. This "likelihood of source confusion" doctrine remains a cornerstone of assessing the scope of trademark rights in relation to goods and services.

The Factual Backdrop: Sake vs. Shochu and the Associated Trademark System

The case arose under Japan's old Trademark Law, which included an "associated trademark" (連合商標 - rengō shōhyō) system. This system, though abolished in 1996, played a role in the procedural history. Generally, it required an applicant's own similar trademarks for the same goods, or identical/similar marks for similar goods, to be filed as associated trademarks.

Company X (the appellee before the Supreme Court) had an existing registered trademark "花橘正宗" (Hana Tachibana Masamune, roughly "Flower Tachibana Sake") for "seishu" (清酒 - refined sake). Subsequently, Company X applied to register "橘正宗" (Tachibana Masamune) for "seishu" as an associated trademark to its original "Hana Tachibana Masamune" registration.

However, a complicating factor arose: after Company X's initial "花橘正宗" trademark was registered, a third party had successfully registered the trademark "橘焼酎" (Tachibana Shōchū, roughly "Tachibana Shochu") for "shochu" (焼酎 - a Japanese distilled spirit).

The Japan Patent Office (JPO) rejected Company X's application for "橘正宗". The JPO reasoned that Company X's applied-for mark "橘正宗" was similar to the third-party's registered mark "橘焼酎". This similarity was primarily based on the common prominent element "橘" (Tachibana), given that "正宗" (Masamune) is a customary term often used in sake brand names to denote quality or authenticity, and "焼酎" (Shōchū) is the generic name for that type of spirit. Furthermore, the JPO considered the respective designated goods—"seishu" (for Company X's application) and "shochu" (for the third-party registration)—to be similar. Consequently, the JPO found that Company X's application fell foul of the non-registrability clause of the old Trademark Law, Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 9 (which corresponds to Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 11 of the current law, prohibiting registration of marks similar to a prior registered mark for identical or similar goods).

Company X appealed this rejection within the JPO, but the appeal board upheld the examiner's decision, maintaining that the marks were similar and the goods (seishu and shochu) were also similar. Company X then filed a lawsuit with the Tokyo High Court, seeking the cancellation of the JPO's appeal board decision.

The Tokyo High Court's "Product Attribute" Approach

The Tokyo High Court reversed the JPO's decision. Its ruling hinged on a finding that "seishu" and "shochu" were not similar goods. The High Court reasoned that while both seishu and shochu are traditional Japanese alcoholic beverages, consumers are highly adept at distinguishing between them based on their distinct characteristics (taste, production method, typical consumption scenarios, etc.). From the standpoint of commercial common sense, the High Court believed it was highly unlikely that consumers would confuse the products themselves. Based on this premise that the goods were dissimilar, the High Court concluded that the conditions for refusal under Article 2(1)(ix) were not met. This approach, focusing on the inherent properties of the products and the likelihood of direct product confusion, is often termed the "Product Attribute Theory" (商品属性説 - shōhin zokuseisetsu).

The JPO then appealed the Tokyo High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling: Focusing on "Likelihood of Source Confusion"

The Supreme Court overturned the Tokyo High Court's judgment and reinstated the JPO's decision to refuse Company X's application. In doing so, the Supreme Court provided a definitive pronouncement on the correct standard for assessing the similarity of goods in trademark law:

- Rejection of the Direct Product Confusion Test: The Court explicitly stated: "Whether designated goods are similar should not be determined, as the original judgment [the High Court decision] held, by whether the goods themselves are likely to be misidentified or confused in trade." This was a clear rejection of the High Court's "product attribute" approach.

- Establishment of the "Likelihood of Source Confusion" Test: Instead, the Supreme Court laid down the following principle: "If, due to circumstances such as the goods normally being manufactured or sold by the same business entity, using identical or similar trademarks on those goods would lead to a likelihood of them being mistaken as goods manufactured or sold by the same business entity, then even if the goods themselves are not likely to be confused with each other, they are to be considered similar goods under Trademark Law..., Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 9." This established the "likelihood of source confusion" (出所混同説 - shussho kondōsetsu) as the guiding doctrine.

Application to Seishu and Shochu:

Applying this test to the goods in question—seishu and shochu—the Supreme Court reasoned as follows:

- Similarity of Marks: The Court first noted that the trademarks "橘正宗" (Tachibana Masamune) and "橘焼酎" (Tachibana Shōchū) shared the common and essential element "橘" (Tachibana), as "正宗" is a customary suffix for seishu brands and "焼酎" is the generic term for shochu. Thus, the marks themselves were considered similar. (The fame of the third-party "橘焼酎" mark was deemed irrelevant to this part of the analysis.)

- Crucial Trade Circumstance: The Supreme Court then highlighted a key factual finding by the High Court: many manufacturers in Japan held licenses to produce and sell both seishu and shochu.

- Likelihood of Source Confusion: Given this common trade practice, the Court concluded: "...if a business entity exists that manufactures shochu using the trademark '橘焼酎' (Tachibana Shōchū), and on the other hand, a business entity exists that manufactures seishu using the trademark '橘正宗' (Tachibana Masamune), it is clear that the general public would likely be mistaken into believing that these products both originate from the same business entity that uses a '橘' (Tachibana) mark to manufacture alcoholic beverages."

- Conclusion on Goods Similarity: Therefore, the Supreme Court held that not only were the trademarks "橘焼酎" and "橘正宗" similar, but their respective designated goods—shochu and seishu—were also to be deemed similar goods precisely because of this likelihood of consumers confusing their commercial origin if similar marks were used.

Based on this finding that both the marks and the goods were similar, the Supreme Court concluded that the JPO had been correct in initially rejecting Company X's application for "橘正宗" under Article 2(1)(ix) of the old Trademark Law.

Deconstructing "Likelihood of Source Confusion" for Goods: Beyond Simple Circularity

The "Tachibana Masamune" decision is pivotal, but legal commentators have pointed out potential pitfalls if the "source confusion theory" is applied too simplistically.

- Avoiding Circular Reasoning: If the theory merely states that "goods are similar if using similar marks on them causes source confusion," it risks becoming circular. The likelihood of source confusion is often the result of pre-existing similarities between marks and between goods; it's the conclusion of the analysis, not the sole premise for determining goods similarity. Such an approach could also blur the lines with provisions like Article 4(1)(xv) of the current law, which deals with likelihood of confusion with another's business even for dissimilar goods.

- The Flaw in Pure "Product Attribute Theory": Conversely, a pure "product attribute theory" that focuses only on whether the physical products themselves would be confused (e.g., would someone mistake a bottle of sake for a bottle of shochu if the labels were removed?) is also inadequate. Trademark law's primary concern is the confusion of commercial source or origin, not merely the confusion of the physical nature of the products.

A Refined "Source Confusion Theory":

A more robust understanding, as advocated by legal scholars and reflected in the nuanced application of the Tachibana Masamune principles, suggests that the "likelihood of source confusion if similar marks are used" should serve as a conceptual guideline. The actual test then involves identifying concrete underlying factors related to the goods themselves and their market context that could cause such source confusion when similar marks are applied. These factors include:

- Product-Related Attributes: Raw materials, quality, purpose/use, physical form, etc. (these are aspects often considered by the "product attribute theory" but are re-contextualized here).

- Relationship between Products: Such as finished goods and their parts or components.

- Business and Trade Channel Overlaps: Identity or significant similarity in production departments, sales departments, distribution channels, and manufacturing processes.

- Consumer Overlap: Commonality of the target consumer base for the goods.

The Supreme Court's reasoning in Tachibana Masamune aligns well with this refined approach. By specifically pointing to the fact that "many manufacturers held licenses for both seishu and shochu," the Court identified a crucial trade channel overlap – a concrete factor that makes it likely for consumers to assume a common origin if they see similar "橘" (Tachibana) branding on both types of alcoholic beverages. This specific circumstance formed a rational basis for finding the goods similar in a trademark context. This analytical framework, focusing on underlying causative factors for potential source confusion, is considered the proper interpretation of the "source confusion theory." These principles are also applicable to determining the similarity between services, and between goods and services.

Impact on JPO Practice and Subsequent Case Law

The principles from Tachibana Masamune have had a lasting impact:

- JPO Trademark Examination Guidelines: The JPO's current Trademark Examination Guidelines for assessing the similarity of goods list several factors that resonate with the refined "source confusion theory." These include whether the goods share: (1) production departments, (2) sales departments, (3) raw materials and quality, (4) purpose/use, and (5) consumer bases, as well as (6) whether they are finished products and parts. Similar criteria are provided for assessing the similarity of services, and between goods and services. The guidelines state that these factors are considered comprehensively to determine if using identical or similar trademarks would likely cause consumers to misidentify the goods/services as originating from the same business. The JPO also publishes "Similar Goods/Services Examination Standards," which group related goods and services (often referred to as being in the same "tanzaku" or coded category), and items within the same group are generally "presumed" to be similar. Contrary to some interpretations, this JPO practice appears to be more aligned with the refined "source confusion theory" than a strict "product attribute theory."

- Subsequent Court Decisions: Japanese courts have generally followed the framework established in Tachibana Masamune, examining various factors related to goods and their market context to determine if a likelihood of source confusion would arise if similar marks were used. Examples include:

- Finding foundry molding machines and welding equipment similar due to the close relationship between casting and welding processes, despite different specific uses.

- Finding metalworking machinery and blades for such machinery similar because they are often manufactured and sold by the same business entities.

- Finding plastic packaging containers and plastic bags/films similar based on shared uses, production/sales departments, materials, and consumer bases.

- Finding computer software and semiconductor chips/elements similar due to commonalities in use, function, producers, retail outlets, and consumers.

- Conversely, semiconductor wafers (a raw material) and integrated circuits (finished electronic components) were found dissimilar because, although some large manufacturers handle both, this is not a widespread industry practice.

- In an infringement case, standard cosmetics and "sexual cosmetics/sundries" were found dissimilar due to differences in their nature, purpose, and sales methods.

In all these instances, courts have based their similarity determinations on an assessment of underlying factors and whether these factors would lead to a likelihood of source confusion if similar trademarks were employed.

Conclusion

The Tachibana Masamune Supreme Court decision was a landmark judgment that fundamentally shifted the paradigm for assessing the similarity of goods in Japanese trademark law. By rejecting a narrow focus on whether products themselves could be confused and instead prioritizing whether the use of similar trademarks on different goods would likely confuse consumers about their commercial origin, the Court established a more practical and contextually relevant standard. This "likelihood of source confusion" test, when applied by considering concrete factors such as shared manufacturing and sales channels, consumer expectations, and product interrelationships, ensures that trademark law effectively protects both business goodwill and consumer interests by preventing misleading indications of origin in the marketplace. The principles articulated in this 1961 ruling continue to underpin the analysis of goods and services similarity in Japan today.