Not a Disease, Not a Discount: Japan's Top Court on "Long Necks" and Damage Reductions in Tort Claims

Date of Judgment: October 29, 1996

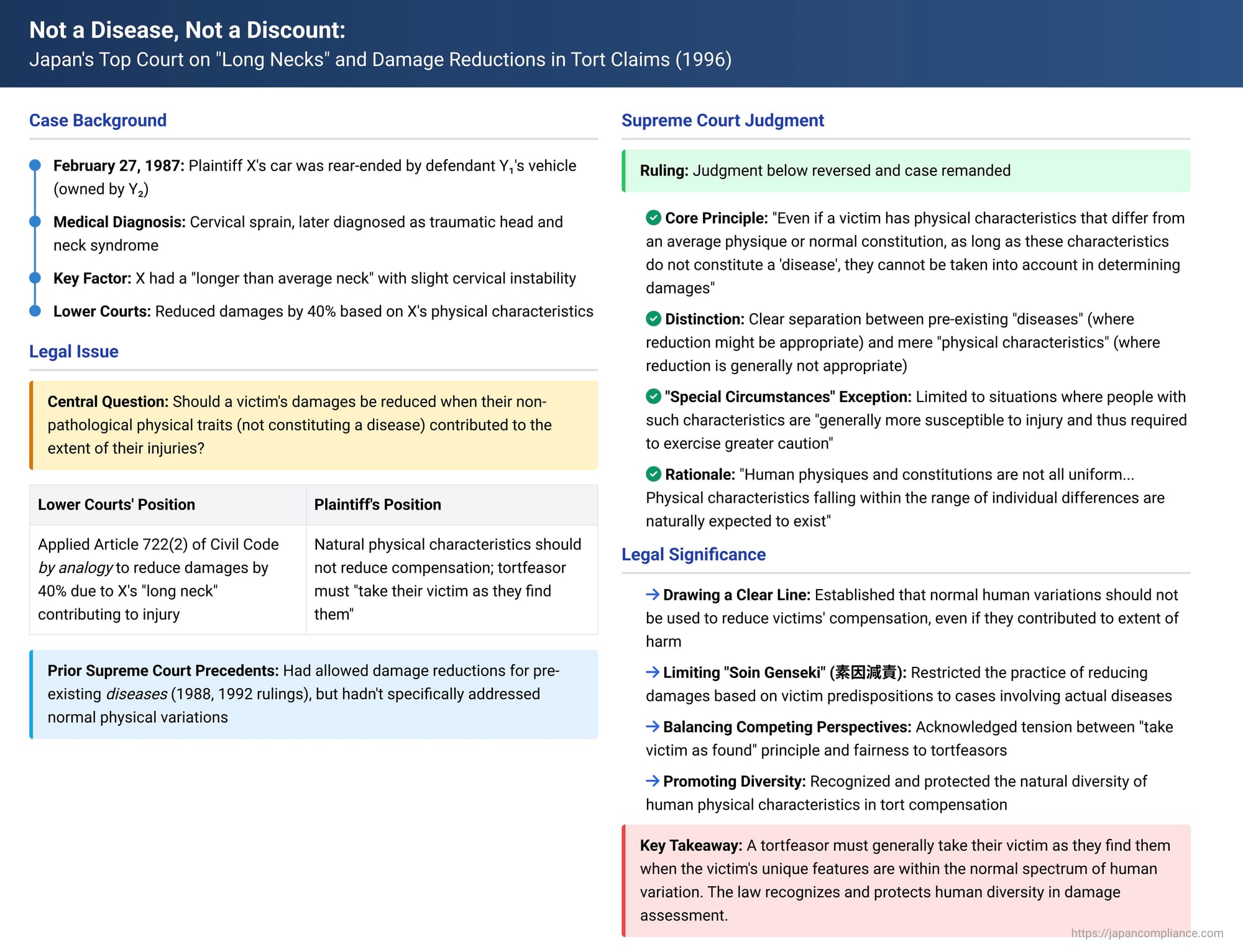

In personal injury law, a long-standing question revolves around how a victim's pre-existing conditions or vulnerabilities should affect the compensation they receive from a tortfeasor. The "eggshell skull rule," a concept familiar in some legal systems, posits that a defendant must take their victim as they find them; if a victim's unusual frailty leads to greater injury than a normal person might have suffered, the defendant is generally liable for the full extent of that aggravated harm. But how does Japanese law approach situations where a victim's unique physical characteristics, not amounting to an actual illness, play a role in the extent of their injuries? A pivotal clarification came from the Supreme Court of Japan on October 29, 1996.

This decision, from the Third Petty Bench (Heisei 5 (O) No. 875), addressed whether a victim's damages should be reduced if their non-pathological physical traits contributed to the harm they suffered, particularly by analogical application of comparative negligence rules.

The Accident and the Lower Courts' Approach to a "Long Neck"

The case involved a plaintiff, X, whose car was rear-ended on February 27, 1987, by a vehicle driven by Y₁ and owned by Company Y₂[cite: 1]. As a result of the collision, X struck her head on the driver's seat. She was diagnosed with a cervical sprain the following day and subsequently experienced persistent symptoms, including pain in her neck and the back of her head, and decreased corrected vision, leading to a diagnosis of traumatic head and neck syndrome[cite: 1].

A crucial element in the case was X's pre-existing physical makeup: she had a neck that was longer than average and, associated with this, some slight instability in her cervical spine[cite: 1].

The lower courts, both at the first instance and on appeal, found Y₁ and Company Y₂ liable for the accident[cite: 1]. However, they determined that X's specific physical characteristics—her long neck and slight cervical instability—had combined with the impact of the accident to cause, aggravate, or expand her symptoms[cite: 1]. Taking these physical traits, as well as "psychological factors," into account, the lower courts decided to apply Article 722, paragraph 2 of the Civil Code (the provision for comparative negligence) by analogy. Consequently, they reduced X's recoverable damages by 40 percent[cite: 1]. X appealed this reduction to the Supreme Court, challenging the appropriateness of diminishing her compensation based on her natural physique.

The Supreme Court's Groundbreaking Clarification

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of October 29, 1996, reversed the lower courts' decision regarding the reduction and remanded the case[cite: 1]. The Court laid down a crucial principle distinguishing pre-existing diseases from mere physical characteristics.

The Core Principle: "Disease" vs. "Physical Characteristic"

The Court stated: "Even if a victim has physical characteristics that differ from an average physique or normal constitution, as long as these characteristics do not constitute a 'disease' (疾患 - shikkan), they cannot be taken into account in determining the amount of damages, unless special circumstances exist"[cite: 1].

This established a clear demarcation. The Court acknowledged its own prior precedents (specifically a Supreme Court First Petty Bench judgment of June 25, 1992, which built on a 1988 ruling) which allowed for the analogical application of comparative negligence rules when a victim's pre-existing disease contributed to the damage, provided that making the tortfeasor bear the entirety of the damages would be unfair given the nature and extent of the disease[cite: 1]. However, the 1996 judgment signaled that physical characteristics not amounting to a disease warrant a different approach.

Application to X's Case: A "Long Neck" is Not a Disease

Applying this principle, the Supreme Court found that X's "long neck and some associated slight cervical spine instability" clearly did not constitute a "disease"[cite: 1].

The "Special Circumstances" Exception – A Narrow Path

The Court did allow for an exception: such non-disease physical characteristics could be considered if "special circumstances" were present[cite: 1]. However, it defined these circumstances quite narrowly, giving the example of a situation where "individuals with such physical characteristics are generally more susceptible to injury and are thus required to exercise greater caution in their daily lives"[cite: 1]. If such a heightened duty of caution due to a specific, known vulnerability exists and is breached by the victim, this might open the door to considering their conduct under actual comparative negligence principles, rather than merely reducing damages by analogy due to the characteristic itself. In X's case, the Court found no evidence that people with long necks are generally expected to be more cautious or are inherently more prone to injury in a way that would trigger these special circumstances[cite: 1].

Rationale: Embracing Normal Human Variation

The Supreme Court's reasoning was rooted in an acknowledgment of natural human diversity: "Human physiques and constitutions are not all uniform... Physical characteristics falling within the range of individual differences are naturally expected to exist"[cite: 1]. Unless a physical characteristic is so extreme (the Court mentioned "extreme obesity" as a hypothetical example where an individual might be more prone to serious injury from a simple fall and thus might be expected to act with greater caution), variations are part of the expected spectrum of human existence[cite: 1]. Therefore, the Court concluded, "even if these physical characteristics and the tortious act in this accident concurred to cause X's injuries, or if these physical characteristics contributed to the aggravation or expansion of the victim's damages, it is not appropriate to consider them in determining the amount of damages"[cite: 1].

The Legal Landscape Leading to the 1996 Ruling

The 1996 decision did not emerge in a vacuum. From around the late 1960s and 1970s, Japanese lower courts had begun, in some cases, to reduce damages if a victim's "soin" (a broad term encompassing pre-existing susceptibilities, conditions, or even age-related changes) contributed to the extent of their loss[cite: 1]. This practice, often referred to as "soin genseki" (素因減責 - reduction due to predisposition), was sometimes justified by invoking the victim's "contribution ratio" to the overall damage[cite: 1].

This trend prompted significant academic debate. Some scholars attempted to justify these reductions through theories of causation (like proportional or partial causation), while others argued that it was a matter of legal evaluation and were often critical of such reductions[cite: 1]. There were also notable lower court decisions, such as a Tokyo District Court ruling in 1989 (often dubbed an "as is" or "take the victim as you find them" judgment), that explicitly rejected the idea of reducing damages based on the victim's predispositions[cite: 1].

Amidst this diverse landscape, two key Supreme Court precedents directly preceded the 1996 ruling:

- A judgment on April 21, 1988, held that where a victim's pre-existing disease and the tortious act together caused harm, courts could, by analogy to comparative negligence, consider the disease in calculating damages if making the tortfeasor bear the full loss would be unfair[cite: 1]. This case involved a psychological predisposition, leading to discussions about the ruling's broader applicability[cite: 1].

- A judgment on June 25, 1992, confirmed that this analogical application of comparative negligence could also apply to a victim's physical pre-existing conditions (specifically, diseases), indicating that the principle was not confined to psychological factors[cite: 1].

These two decisions established that "soin genseki" was a permissible approach under Japanese law, particularly for pre-existing diseases, but they did not clearly delineate the boundaries of what constituted a "soin" eligible for such consideration, nor did they explicitly exclude non-disease physical traits[cite: 1]. The lower courts in X's case, therefore, could have arguably seen their reduction as consistent with these precedents[cite: 1].

Significance of the 1996 Ruling: Drawing a Line

The Heisei 8 (1996) Supreme Court judgment is significant primarily because it drew a critical line:

- It established a general rule that ordinary physical characteristics, differing from an average physique but not amounting to a "disease," should not be a basis for reducing a victim's damages, even if those characteristics contributed to the extent of the harm[cite: 1].

- By doing so, it implicitly endorsed a version of the "take your victim as you find them" principle for characteristics that fall within the normal spectrum of human anatomical variation.

- It clarified that the "special circumstances" that might allow such a characteristic to be considered are narrow, typically pointing towards situations where the victim might have a recognized duty to exercise greater personal caution due to that specific trait, potentially bringing it closer to standard comparative negligence if that duty is breached[cite: 1]. This significantly limits the scope for reducing damages by analogy for mere physical traits[cite: 1].

Ongoing Debates and Interpretations in Light of the Ruling

The 1996 decision, while providing clarity, also highlighted ongoing theoretical discussions in Japanese law regarding "soin genseki."

The "Disease" vs. "Characteristic" Distinction:

A key practical and theoretical challenge is objectively distinguishing between a "disease" and a "physical characteristic." [cite: 1] For example, how should age-related degenerative changes be classified? [cite: 1] Furthermore, what is the underlying legal or ethical justification for treating these two categories differently when it comes to damage compensation? [cite: 1]

Two Fundamental (and Competing) Perspectives on Predisposition:

The commentary on this case suggests that understanding the 1996 ruling requires acknowledging two broad, often conflicting, foundational viewpoints on how a victim's predispositions should be handled in tort law[cite: 1]:

- Viewpoint 1: Tortfeasor Generally Does Not Bear Responsibility for Predisposition Effects (Pro-Reduction as Default).

This stance begins with the premise that a tortfeasor should not, as a general rule, be responsible for harms that are specifically attributable to the victim's unique internal conditions. Reduction of damages is seen as the baseline. The legal inquiry then focuses on identifying exceptional circumstances under which the tortfeasor would be required to compensate for damages exacerbated by a predisposition[cite: 1]. From this perspective, the 1996 Supreme Court ruling is significant because it carves out an exception to the general rule of reduction. This exception covers "physical characteristics within the range of individual variation," effectively saying that these common variations are not "soin" for reduction purposes unless they meet the "special circumstances" test[cite: 1]. The concept of "individual variation," possibly linked to what a tortfeasor might reasonably foresee, becomes more critical than a strict formal distinction between disease and characteristic[cite: 1]. - Viewpoint 2: Tortfeasor Must "Take the Victim as They Find Them" (Anti-Reduction as Default).

This view emphasizes that society is composed of individuals with diverse physical and mental makeups. Tort law should, therefore, start from the premise of the actual, concrete victim rather than an abstract "average" or "standard" person[cite: 1]. This generally leads to a rejection of predisposition-based damage reductions. Legal maxims from other jurisdictions, such as the "eggshell skull rule" in Anglo-American law or the German legal principle that a tortfeasor who harms a frail person cannot claim to be treated as if they had harmed a healthy one, embody this value judgment[cite: 1]. From this standpoint, the 1996 Supreme Court's statement that "human physiques and constitutions are not all uniform" is seen as aligning with the principle of starting with the actual victim, even if it is qualified by the idea of characteristics being "within the range of individual variation"[cite: 1]. Because perfect health is not the norm, this perspective can extend to diseases as well. Previous Supreme Court rulings that permitted reductions for diseases would then be viewed as the exception, applicable only in limited situations where compelling the tortfeasor to cover all damages would be manifestly "unfair"[cite: 1].

The 1996 judgment navigates these complex theoretical waters by affirming its prior decisions regarding diseases (allowing for reduction under fairness considerations) while drawing a new and important line that largely shields victims from reductions based on non-disease physical characteristics. Reconciling this judgment with earlier ones requires acknowledging these underlying theoretical tensions rather than relying on a simplistic disease/characteristic dichotomy[cite: 1].

Conclusion: Advancing Fairness by Acknowledging Human Diversity

The Supreme Court of Japan's decision of October 29, 1996, represents a significant refinement in the country's tort law concerning victim predispositions. Its core message is that ordinary physical variations which do not rise to the level of a "disease" should generally not lead to a reduction in a victim's rightful compensation, even if those traits played a role in the extent of their suffering.

This ruling champions a notion of fairness that acknowledges the natural diversity of human beings. While the door remains open for considering pre-existing diseases in damage calculations under specific equitable criteria, the Court has made it clear that one's unique but non-pathological physical makeup is, for the most part, something a tortfeasor must take as it comes. This judgment is a crucial step in delineating how individual vulnerabilities are treated in the pursuit of just compensation, ensuring that the principle of "soin genseki" is applied with careful consideration and clear limits.