Normal Wear and Tear in Japanese Leases: Supreme Court Sets High Bar for Shifting Repair Costs to Tenants

Judgment Date: December 16, 2005

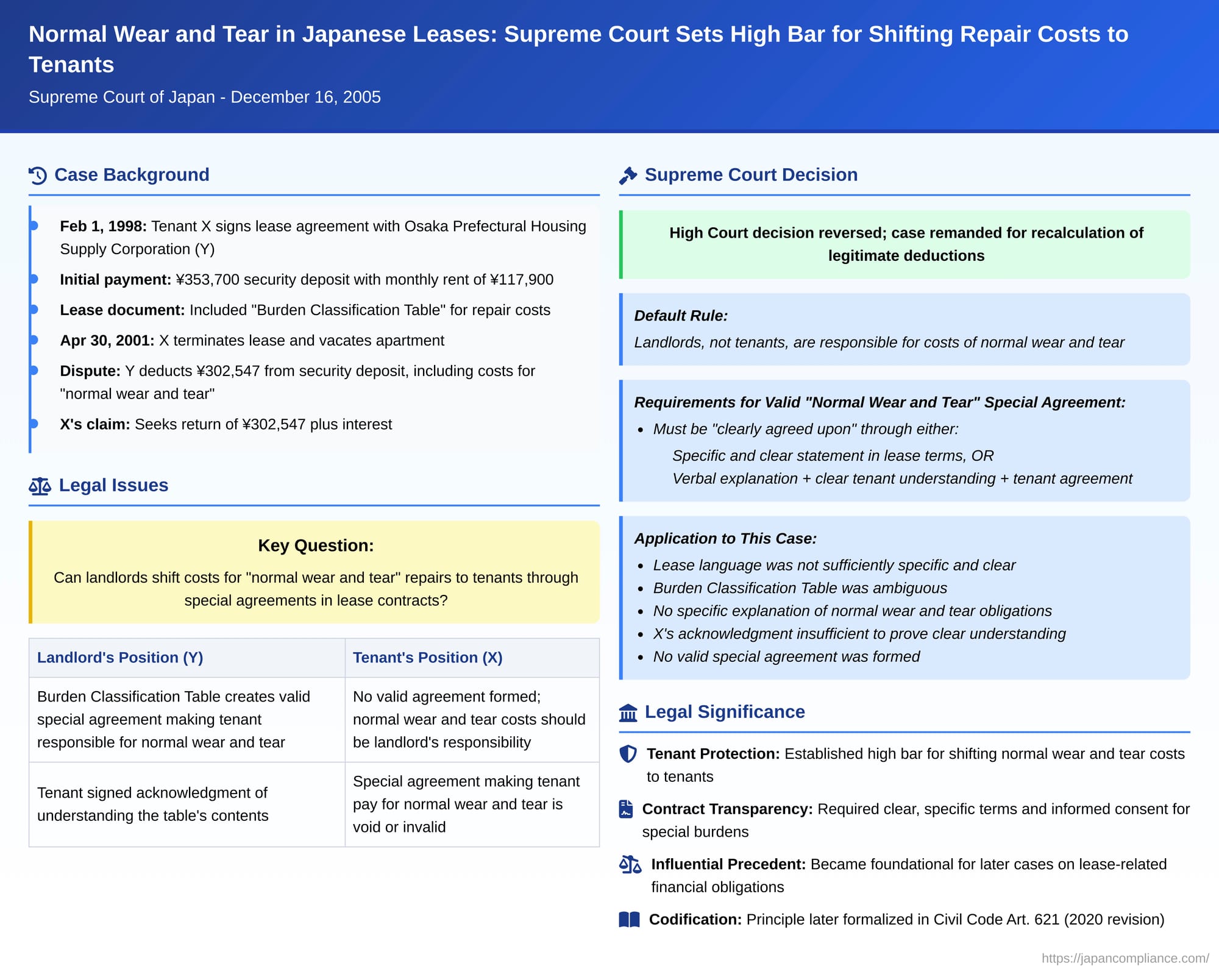

A common point of contention between landlords and tenants in Japan, as in many countries, revolves around the state of a rental property upon move-out and who bears the cost for repairs. Specifically, the issue of "normal wear and tear" versus actual "damage" often leads to disputes over security deposit deductions. In a landmark decision on December 16, 2005 (Heisei 16 (Ju) No. 1573), the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan provided significant clarification on this issue, establishing the default rule for normal wear and tear and setting stringent requirements for any special agreements that seek to shift these costs to tenants. The case involved an individual tenant, X, and a public entity, the Osaka Prefectural Housing Supply Corporation (Y), acting as the landlord.

The Lease Agreement and the Security Deposit Dispute

The factual background of the case is as follows:

On February 1, 1998, well before Japan's Consumer Contract Act came into full effect (April 1, 2001), X (the tenant) entered into a lease agreement with Y (the landlord) for an apartment in a multi-unit residential complex. The monthly rent was ¥117,900, and X paid a security deposit (敷金 - shikikin) of ¥353,700.

On April 30, 2001, X terminated the lease and vacated the apartment. Subsequently, Y deducted ¥302,547 from X's security deposit to cover repair costs. Critically, these deductions included expenses for rectifying what Y considered "normal wear and tear" (通常損耗 - tsūjō sonmō)—the kind of minor deterioration that occurs from ordinary, everyday living. Y returned only the remaining ¥51,153 to X.

The lease agreement signed by X and Y contained clauses stipulating the tenant's duty to restore the premises to their original condition upon vacating. It specified that repair costs were to be borne by the tenant according to a "Burden Classification Table" (負担区分表 - futan kubun hyō), which was attached as a separate document, based on Y's instructions. This table, titled "Standard for Bearing Costs of Repairs, etc., After Vacancy," itemized various repair categories, the conditions necessitating repair, the proposed repair methods, and which party was responsible for the cost. For instance, the table indicated that for "various floor finishing materials," any "discoloration, soiling, damage recognized as occurring from ordinary living" was to be the tenant's financial responsibility. The table also provided definitions for terms like "damage" (破損 - hason, meaning broken or breaking/damaging) and "soiling" (汚損 - oson, meaning soiled or soiling/damaging).

Prior to signing the lease, Y had conducted an information session for prospective tenants. During this session, Y distributed copies of the lease agreement and a booklet titled "Guide to Living" (すまいのしおり - sumai no shiori), which included explanations of the repair cost standards. Y's representatives provided a general overview of important lease clauses and mentioned that repair costs upon vacating would be determined according to the Burden Classification Table. However, specific individual items within this table, particularly how they applied to normal wear and tear, were not individually explained. Upon signing the lease, X submitted a document affirming that they understood the contents of the Burden Classification Table.

X initiated a lawsuit, arguing that any special agreement purporting to make tenants liable for normal wear and tear repair costs was either not validly formed or was void (e.g., as being against public policy and good order). X asserted that no amount should have been deducted for such repairs and sought the return of the ¥302,547 withheld from the security deposit, plus accrued interest. Both the Osaka District Court and the Osaka High Court ruled against X, upholding Y's deductions. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Default Rule: Landlord Bears Normal Wear and Tear Costs

The Supreme Court began its judgment by affirming a fundamental principle of Japanese tenancy law regarding the tenant's duty to restore the leased property to its original condition (原状回復義務 - genjō kaifuku gimu). The Court stated:

- A lease agreement, by its very nature, involves the tenant using the leased property and the landlord receiving rent as consideration for this use.

- The occurrence of some level of wear, tear, and depreciation of the property due to its use over the lease term is a naturally anticipated consequence.

- Therefore, in the context of building leases, the financial recovery for "normal wear and tear"—defined as the deterioration or decrease in value of the leased property resulting from the tenant's socially accepted ordinary use—is typically achieved by the landlord through the rent collected. Rent is generally understood to include components covering such depreciation and the ordinary repair expenses the landlord will eventually incur.

From this, the Supreme Court concluded that a tenant's standard obligation to restore the property to its "original condition" upon termination of the lease does not inherently include the obligation to repair or pay for normal wear and tear. Such costs are, by default, the landlord's responsibility. This clarification by the Supreme Court was significant, as while this principle was widely accepted, it had not been explicitly affirmed at the highest judicial level prior to this decision. This principle was later formally codified in Article 621 of the revised Civil Code (effective April 2020), which states that the tenant is not responsible for restoring damage resulting from ordinary use or aging.

Shifting the Burden: The Strict Requirements for a "Normal Wear and Tear Repair Special Agreement"

While establishing the default rule, the Supreme Court acknowledged that parties to a lease can mutually agree to deviate from it through a special agreement or clause (特約 - tokuyaku) that makes the tenant responsible for normal wear and tear repair costs. However, the Court emphasized that imposing such an obligation on a tenant constitutes an "unexpected special burden" (予期しない特別の負担 - yoki shinai tokubetsu no futan).

Consequently, for such a "normal wear and tear repair special agreement" (通常損耗補修特約 - tsūjō sonmō hoshū tokuyaku) to be valid and enforceable, it must be "clearly agreed upon" (明確に合意されている - meikaku ni gōi sarete iru). The Supreme Court outlined two alternative conditions under which such a clear agreement could be established:

- Explicitly and Specifically in the Written Contract: The scope of normal wear and tear repairs that the tenant is to bear the cost for must be "specifically and clearly stated in the terms of the lease agreement itself." The language used must be unambiguous and leave no doubt as to the tenant's additional responsibility.

- Verbal Explanation and Clear Tenant Understanding and Assent: If the written lease agreement is not sufficiently clear on this point, then it must be demonstrable that:

- The landlord (or their representative) verbally explained the specific details of the tenant's obligation to cover normal wear and tear.

- The tenant clearly understood the nature and extent of this obligation.

- The tenant agreed to this obligation as part of the contract's content.

Application to the Case: No "Clear Agreement" Found

Applying these stringent criteria to the facts of X's case, the Supreme Court found that a valid special agreement imposing normal wear and tear repair costs on X had not been formed:

- Lease Agreement Insufficiently Clear: The relevant clause in the lease agreement (Article 22, Paragraph 2), which outlined the tenant's restoration duties, did not, in itself, specifically and clearly detail that normal wear and tear repairs were the tenant's burden.

- "Burden Classification Table" Ambiguous: While the lease referred to the "Burden Classification Table," the Court found this table also lacking in clarity. Phrases used in the table to describe conditions requiring repair, such as "conditions serving as a standard" (基準になる状況 - kijun ni naru jōkyō), were not considered "unambiguously clear" in conveying that costs for normal wear and tear (like "discoloration from ordinary living") were to be borne by the tenant.

- Pre-Contract Information Session Lacked Specificity: The explanation provided by Y's representatives at the pre-contract information session, while generally mentioning that move-out repair costs would be based on the Burden Classification Table, did not specifically address or clarify the content of a special agreement regarding normal wear and tear repairs. The individual items and their application to normal wear and tear were not explained.

- Tenant's Acknowledgment Insufficient: The fact that X had submitted a document stating they understood the contents of the Burden Classification Table did not, in the Supreme Court's view, overcome the lack of clarity in the table itself and the absence of specific explanations. It could not be concluded from this that X had recognized and specifically agreed to bear the costs of normal wear and tear as a distinct contractual obligation.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that X could not be said to have understood and agreed to a special agreement making them liable for normal wear and tear repairs. As such, no valid agreement to that effect was formed between X and Y. The High Court's decision was reversed, and the case was remanded for a recalculation of the repair costs that Y could legitimately deduct from X's security deposit, this time excluding any costs attributable to normal wear and tear.

Implications of the "Clear Agreement" Standard

This Supreme Court ruling has had a profound impact on landlord-tenant law in Japan:

- High Bar for Landlords: It establishes a demanding standard for landlords who wish to deviate from the default position and make tenants pay for normal wear and tear. Vague, general, or boilerplate clauses are unlikely to suffice. The burden and scope of such costs must be made crystal clear.

- Emphasis on Transparency and Informed Consent: The decision champions the principles of transparency and informed consent in lease agreements. Tenants must genuinely understand and explicitly agree to any "special burdens" like assuming costs for normal wear and tear. This aligns with broader consumer protection ideals that advocate for clarity and fairness in contractual terms.

- Foundation for Later Rulings: This judgment served as a foundational precedent for subsequent Supreme Court decisions concerning other types of lease-related financial obligations beyond basic rent, such as non-refundable portions of security deposits (shikibiki - 敷引特約) and lease renewal fees (kōshinryō - 更新料特約). In those later cases, the Court similarly emphasized the necessity of clear, specific, and demonstrably agreed-upon terms.

- Preventing Potential Double Recovery: By insisting on clear agreements, the ruling helps to prevent situations where landlords might effectively charge tenants twice for normal wear and tear—once implicitly through the rent (which is presumed to cover such depreciation) and then again explicitly through repair charges deducted from the security deposit at the end of the lease.

- Clarity in Standard Forms: The case demonstrates that even when landlords use standardized forms, tables, or schedules (like Y's "Burden Classification Table"), the content of these documents must be self-evidently clear regarding non-standard obligations, or they must be accompanied by thorough and specific explanations to the tenant.

Formation of Agreement vs. Substantive Validity

It is important to note that the Supreme Court's decision in this case focused on whether the special agreement regarding normal wear and tear was validly formed—that is, whether there was a "clear agreement" based on the tenant's informed understanding and consent. The Court did not rule on the substantive validity of such a clause, i.e., whether such a clause, even if clearly agreed upon, might still be deemed void under other legal principles, such as being contrary to public policy or, for contracts entered into after its enforcement, violating Article 10 of the Consumer Contract Act (which nullifies contractual clauses that unilaterally prejudice the interests of consumers in violation of the principle of good faith). This remains a potential, separate avenue for challenging such clauses.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's December 2005 ruling in the Osaka Prefectural Housing Supply Corporation case was a significant victory for tenant rights in Japan. It firmly established that landlords are, by default, responsible for the costs associated with normal wear and tear of a rental property. While parties can agree to alter this default position, any special agreement seeking to transfer these costs to the tenant must meet a high standard of clarity and explicitness, ensuring the tenant's informed and unambiguous consent. This judgment continues to shape the landscape of residential leasing by promoting fairness, transparency, and a clearer understanding of rights and obligations between landlords and tenants.