No Second Guessing: Japan's Supreme Court on the Finality of Administrative Adjudications

A First Petty Bench Ruling from January 21, 1954

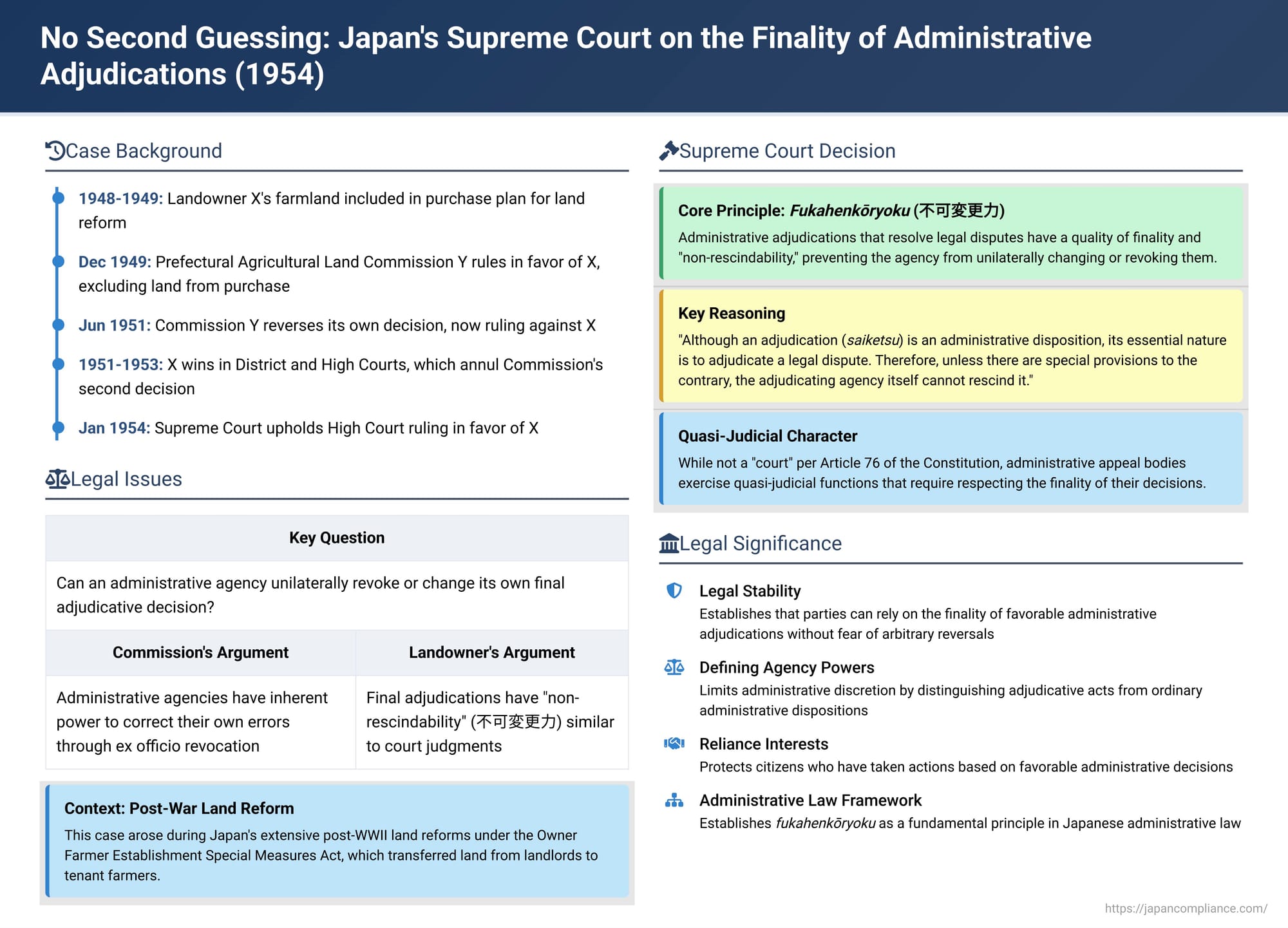

When an administrative agency makes a formal decision after a process of deliberation or appeal, can it later simply change its mind and overturn that decision if it thinks it made a mistake? This question goes to the heart of legal stability and the principle of finality in administrative justice. A 1954 decision by the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan (Showa 25 (O) No. 354) provided a foundational ruling on this issue, establishing the important concept known in Japanese administrative law as fukahenkōryoku (不可変更力), or "non-rescindability," for certain types of administrative adjudications.

The Land Dispute: A Series of Conflicting Decisions

The case arose in the context of Japan's extensive post-World War II land reforms, governed by the Owner Farmer Establishment Special Measures Act (OFESMA - 自作農創設特別措置法 Jisaku-nō Sōsetsu Sochi Hō). This act aimed to transfer land from landlords to tenant farmers to create a broader base of owner-farmers.

The plaintiff, X, was a landowner whose farmland was included in a land purchase plan (農地買収計画 - nōchi baishū keikaku) formulated by the A Village Agricultural Land Commission. The plan identified X's land as uncultivated and therefore subject to compulsory purchase by the government for redistribution to create new owner-farmers.

X disputed this assessment and initiated the following administrative procedures:

- Objection to Village Commission: X filed an objection (異議申立て - igi mōshitate) with the A Village Agricultural Land Commission, asserting that the land was not uncultivated and should not be subject to purchase. The Village Commission dismissed X's objection.

- Appeal to Prefectural Commission: X then filed a formal administrative appeal (sogan - 訴願) with Y, the Hyogo Prefectural Agricultural Land Commission (hereinafter "Prefectural Commission"), challenging the Village Commission's decision, as permitted under OFESMA Article 7, paragraph 4.

- Prefectural Commission's First Adjudication: After reviewing the appeal, the Prefectural Commission Y issued an adjudication (裁決 - saiketsu) in favor of X. This decision concluded that X's land was indeed self-cultivated farmland (jisaku nōchi) and therefore ordered the A Village Agricultural Land Commission to exclude it from the land purchase plan. This adjudication, issued in December 1949, appeared to settle the matter in X's favor.

- The Reversal – Prefectural Commission's Second Adjudication: However, the story did not end there. Approximately three months after its initial favorable ruling for X, the Prefectural Commission Y, prompted by a "petition" (陳情 - chinjō) from the A Village Agricultural Land Commission requesting reconsideration (saigi), revisited its earlier decision. In June 1951, the Prefectural Commission Y issued a new adjudication which completely reversed its previous stance. In this second decision, it found that X's land was uncultivated. Consequently, this new adjudication:

- Annulled its own prior decision of December 1949 (which had favored X).

- This time, upheld Y's (the landowner's, now represented by X in the Supreme Court appeal against the Commission) original contention in the appeal (which it had previously dismissed).

- As a result, it effectively annulled the A Village Agricultural Land Commission's initial adjudication from July 1948 that had designated X's land for purchase (by reversing its own prior decision that had ordered X's land excluded).

This second action by the Prefectural Commission meant X's land was once again subject to compulsory purchase.

The Lawsuit: Challenging the Reversal

In response to this reversal, X filed a lawsuit in court, seeking the annulment of the Prefectural Commission Y's second adjudication—the one from June 1951 that had revoked its earlier favorable decision. Both the Kobe District Court (first instance) and the Osaka High Court (second instance) ruled in favor of X, annulling the Prefectural Commission's second decision. The High Court reasoned that an adjudicative decision made by an administrative appeal body, much like a court judgment, is binding on the body that made it. It held that unless there are specific legal provisions allowing for review (such as provisions for a re-trial similar to those in civil procedure, or other special laws like a specific provision in the Agricultural Land Adjustment Act which was not applicable here), the adjudicating body cannot unilaterally overturn its own final decision simply because it later believes it made a factual error, particularly if that error was due to insufficient deliberation in the first instance. The Prefectural Commission Y then appealed this High Court ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision of January 21, 1954

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal lodged by the Hyogo Prefectural Agricultural Land Commission (Y), thereby upholding the High Court's decision which had annulled Y's second, self-reversing adjudication.

Core Reasoning – The Principle of Fukahenkōryoku (Non-Rescindability):

- The Nature of the Adjudication (Saiketsu): The Supreme Court acknowledged that an adjudication (saiketsu) made by an administrative body like the Prefectural Agricultural Land Commission is, without doubt, an "administrative disposition" (行政処分 - gyōsei shobun). However, the Court stressed that when viewed in substance, the essential nature of such an adjudication is "to adjudicate a legal dispute" (法律上の争訟を裁判するもの - hōritsujō no sōshō o saiban suru mono).

The Court noted that while Article 76, paragraph 2 of the Constitution of Japan states that "No extraordinary tribunal shall be established, nor shall any organ or agency of the Executive be given final judicial power," it does not prevent administrative agencies from conducting quasi-judicial proceedings as a preliminary instance before matters reach the courts. The Prefectural Commission's adjudication in this case, although an administrative disposition because it was made by an administrative body, was substantively an act of adjudicating a legal dispute. - Non-Rescindability of Such Adjudications: Because of this quasi-judicial character, the Court held that such an adjudication "differs from other general administrative dispositions." Therefore, "unless there are special provisions [in law] to the contrary, it is appropriate to construe, as the original judgment (the High Court decision) did, that the adjudicating agency itself cannot rescind it."

This principle, that certain types of administrative acts (especially those resolving disputes in a quasi-judicial manner) cannot be unilaterally revoked or altered by the issuing agency once they have become final, is known in Japanese administrative law scholarship as fukahenkōryoku (不可変更力), often translated as "non-rescindability" or "irrevocability." - Conclusion on the Merits: The High Court was therefore correct in determining that the Prefectural Agricultural Land Commission's act of rescinding its own prior final adjudication and issuing a new, contradictory one was illegal. The arguments presented by the appellant (the Prefectural Commission Y) were found to be without merit.

Understanding Fukahenkōryoku (Non-Rescindability / Irrevocability)

This judgment is a foundational Supreme Court decision that clearly articulates and applies the principle of fukahenkōryoku.

- Meaning: Fukahenkōryoku signifies that certain administrative acts, particularly those which are adjudicative in nature and definitively determine the rights and obligations of parties after a process involving a dispute, acquire a quality of finality. This finality generally prevents the administrative agency that issued the act from arbitrarily changing or revoking it, even if the agency later believes its initial decision was erroneous or unwise.

- Rationale: This principle serves several important functions:

- It promotes legal stability and predictability. Parties affected by such decisions need to be able to rely on their finality.

- It protects the reliance interests of those who have acted on the basis of the decision.

- It prevents the endless re-opening or "re-hashing" (蒸し返し - mushikaeshi) of disputes within the administrative system.

- It is analogous to the principles of self-binding effect (jibakusei, an agency being bound by its own decision) and, more broadly, res judicata (the finality of judicial decisions) that apply to court judgments.

- Distinction from General Ex Officio Annulment Power: Administrative agencies are generally understood to possess an inherent power to annul their own illegal administrative dispositions on their own initiative (職権取消し - shokken torikeshi). However, fukahenkōryoku acts as a limitation on this general power for specific categories of administrative acts, particularly those that are quasi-judicial. The Supreme Court recognized that the adjudicative acts of agricultural land commissions fall into this special category. The commentary notes that the power of ex officio annulment is generally assumed unless specific doctrines like fukahenkōryoku restrict it.

Context and Scope of Application

The Supreme Court's reasoning was heavily influenced by the nature of the administrative process in question.

- The Prefectural Agricultural Land Commission was acting as an appellate body, adjudicating a dispute between a landowner (X) and a lower administrative body (the Village Commission A). This function was inherently quasi-judicial.

- The legal commentary suggests that the legal framework at the time, which involved the recent abolition of the pre-war system of administrative courts and the establishment of administrative litigation within the ordinary court system (under the then-new Administrative Case Litigation Special Provisions Act of 1948), alongside the continuation of pre-war administrative appeal systems like the sogan, likely led the Court to view decisions on such appeals as having a significant dispute-resolution finality akin to a first-instance judicial ruling.

- While this judgment established fukahenkōryoku for such adjudications, legal scholars have debated its precise scope and applicability to other types of administrative acts. It is generally agreed that the principle applies most strongly to quasi-judicial decisions that determine rights and obligations after a formal dispute resolution process.

Significance of the Ruling

The 1954 Supreme Court decision in this case is a landmark for several reasons:

- It provided one of the earliest and most explicit affirmations by the post-war Supreme Court of the principle of fukahenkōryoku (non-rescindability) for quasi-judicial administrative adjudications.

- It limited the power of administrative agencies to unilaterally revisit and overturn their own final, rights-determining decisions, thereby bolstering legal certainty and the protection of individuals who have obtained favorable administrative rulings.

- It distinguished these types of adjudicative administrative acts from ordinary administrative dispositions, which might be more freely subject to ex officio annulment or modification by the issuing agency if found to be illegal or inappropriate.

Contemporary Relevance and Ongoing Discussion

The principle of fukahenkōryoku remains an important concept in Japanese administrative law. However, the legal commentary provided with this case also touches upon ongoing discussions regarding its contemporary application.

- For example, with the evolution of administrative procedures, including the enactment of the Administrative Procedure Act (1993) and significant revisions to the Administrative Appeal Act (2014), the procedural safeguards in administrative processes have changed. The commentary suggests that while modern administrative appeal procedures have enhanced fairness (e.g., through the introduction of hearing officers and review by administrative appeal boards), they may still not possess the full neutrality and adversarial rigor of judicial proceedings. This might lead to questions about whether the analogy to the finality of court judgments, which underpins fukahenkōryoku, holds equally strongly for all types of administrative appeal decisions today.

- There is also discussion about whether fukahenkōryoku should apply with equal force to adjudications that grant relief to an appellant (an "affirmative" or 認容 - nin'yō decision, as in X's initial favorable ruling from the Prefectural Commission) versus those that dismiss or reject an appeal (a "negative" or 棄却・却下 - kikyaku・kyakka decision). It is argued that there might be less need to strictly prevent an agency from correcting its own errors in a negative decision if doing so would benefit the appellant and rectify an injustice without unduly harming others. This judgment specifically dealt with an agency attempting to undo an affirmative decision it had previously made.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1954 decision in the Hyogo Prefectural Agricultural Land Commission case is a foundational judgment in Japanese administrative law concerning the finality of administrative decisions. It firmly established that quasi-judicial adjudications by administrative bodies, once finalized, are generally not subject to unilateral revocation or alteration by the issuing agency itself, even if the agency later believes its initial decision was flawed. This principle of fukahenkōryoku, or non-rescindability, serves as a crucial safeguard for legal stability and the protection of rights determined through formal administrative dispute resolution processes. It ensures that parties can rely on the finality of such decisions, preventing administrative bodies from arbitrarily re-opening settled matters, and underscores the quasi-judicial nature of certain administrative functions.