No Room for Discretion: The Supreme Court's Stance on Minamata Disease Certification and Judicial Review

Date of Judgment: April 16, 2013, Third Petty Bench, Supreme Court of Japan

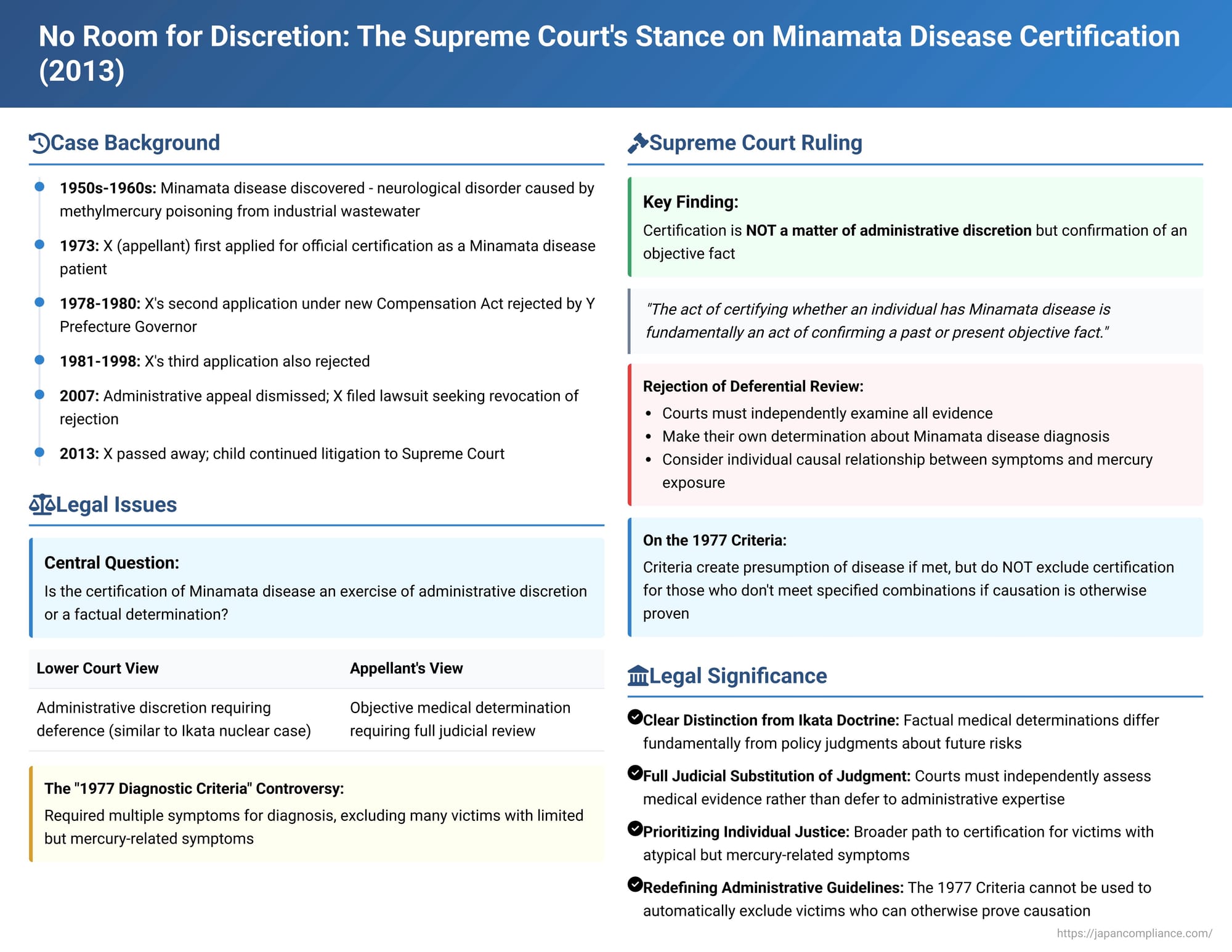

The tragic story of Minamata disease, a debilitating neurological illness caused by industrial mercury poisoning, represents one of Japan's most severe pollution incidents. For decades, victims have fought for official recognition and compensation. A landmark decision by the Japanese Supreme Court on April 16, 2013, significantly impacted this struggle by clarifying the nature of Minamata disease certification and fundamentally reshaping the judiciary's role in reviewing such administrative decisions. The Court's ruling emphasized that determining whether an individual suffers from Minamata disease is a matter of factual ascertainment, not administrative discretion, thereby mandating a more searching standard of judicial review.

The Factual Background: A Decades-Long Quest for Recognition

The appellant, X, was born in 1925 in Minamata City (located in Y Prefecture, a pseudonym for Kumamoto Prefecture where Minamata is situated) and resided there until 1971. X began experiencing symptoms such as numbness in the legs around 1972.

- Initial Applications and Rejections:

- In April 1973, X first applied for official certification as a Minamata disease patient under the then-existing "Act on Special Measures for the Relief of Pollution-related Health Damage" (hereinafter, the Relief Act). This application was rejected by the Governor of Y Prefecture in May 1978.

- In September 1978, X applied again, this time under the newly enacted "Pollution-related Health Damage Compensation Act" (hereinafter, the Compensation Act), which had replaced the Relief Act. After consulting the Y Prefecture Pollution-related Health Damage Certification Council (the Prefectural Certification Council), the Governor of Y Prefecture rejected this second application in May 1980. This 1980 rejection became the specific administrative action (the Current Disposition) challenged in the present lawsuit.

- X filed a third application in October 1981, which was also rejected in March 1998.

- Administrative Appeal and Lawsuit:

- An administrative appeal by X to the Pollution-related Health Damage Compensation Grievance Review Board (the Grievance Review Board) was dismissed in March 2007.

- In May 2007, X filed a lawsuit seeking the revocation of the Current Disposition (the 1980 rejection) and an order compelling the Governor of Y Prefecture to certify X as a Minamata disease patient.

- During the course of the legal proceedings, X passed away in March 2013. X's child took over the litigation and subsequently applied to the Governor for a decision formally recognizing that X had been eligible for certification.

- Lower Court Decisions: The first instance court (Osaka District Court) ruled in favor of X, accepting the claims. However, the second instance court (Osaka High Court) reversed this decision, finding no illegality in the Governor's rejection of X's certification application. The High Court had applied a deferential standard of review similar to that used in cases involving highly technical administrative discretion, such as the Ikata Nuclear Power Plant case.

The Legal and Historical Context: Minamata Disease and Its Recognition

Understanding the Supreme Court's decision requires some background on Minamata disease and the legal framework for victim relief:

- Minamata Disease: This neurological syndrome is caused by severe methylmercury poisoning. It was first discovered in Minamata City in the 1950s. The source of the mercury was industrial wastewater discharged by Company C (Chisso Corporation) from its chemical factory in Minamata. The methylmercury accumulated in fish and shellfish in Minamata Bay and the Shiranui Sea, which were then consumed by the local population, leading to the disease. Symptoms include sensory disturbances (numbness in limbs), ataxia (lack of muscle control), dysarthria (slurred speech), constriction of the visual field, and hearing impairment[cite: 1, 3].

- Relief Legislation: The Relief Act (1969) and its successor, the Compensation Act (1974), established a system for official certification of pollution-related diseases, including Minamata disease. Under the Compensation Act, prefectural governors are responsible for certifying individuals as patients if their illness is determined to be caused by designated pollutants in specified areas (Minamata disease is designated as a "specific disease" linked to methylmercury in the Minamata Bay area)[cite: 1, 3]. This certification is based on an application from the individual and an opinion from an expert Prefectural Certification Council[cite: 1, 3]. Certified patients are eligible for compensation benefits[cite: 3].

- The "1977 Diagnostic Criteria": In 1977, the Environment Agency issued a notification outlining diagnostic criteria for Minamata disease (the 1977 Diagnostic Criteria or 1977 Criteria). These criteria generally required a combination of multiple neurological symptoms for a definitive diagnosis[cite: 1, 3]. This led to many individuals who exhibited only some symptoms, such as sensory disturbances alone (even if linked to mercury exposure), being denied certification[cite: 3]. This was a point of significant contention, as an earlier 1971 Vice-Minister's notification from the Environment Agency had emphasized a more comprehensive medical judgment[cite: 1, 3].

The Supreme Court's Decision of April 16, 2013

The Supreme Court reversed the Osaka High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings, effectively instructing the lower court to re-evaluate X's claim using a more stringent, non-deferential standard of review.

1. Definition and Nature of Minamata Disease under the Law

The Court clarified the legal understanding of Minamata disease:

- Although the Compensation Act and related laws (referred to collectively as "公健法等" - Kōkenhō tō) do not explicitly define Minamata disease, the Court found, based on established facts (including an expert committee opinion that influenced the original legislation), that Minamata disease under these laws should be understood as "a neurological disorder caused by oral ingestion of methylmercury accumulated in fish and shellfish"[cite: 1].

- The Court noted that there was no evidence to suggest that the laws intended to define Minamata disease differently from this objective, etiological understanding[cite: 1]. Minamata disease is classified as a "specific disease" (特異的疾患 - tokuiteki shikkan), meaning it has a unique causal link to a specific pollutant (methylmercury) and would not occur in its absence[cite: 1].

2. Rejection of Administrative Discretion in Certification

This was a crucial part of the judgment. The Court held that:

- The act of certifying whether an individual has Minamata disease is fundamentally an act of confirming a past or present objective fact[cite: 1].

- This determination—whether an applicant suffers or suffered from Minamata disease as an objective phenomenon—is not a matter to be left to the administrative agency's discretion[cite: 1].

3. Standard of Judicial Review: Full Substitution of Judgment

Based on the non-discretionary nature of the certification, the Court mandated a more intensive form of judicial review:

- The Court explicitly rejected the High Court's approach, which had adopted a deferential review standard similar to that used in the Ikata Nuclear Power Plant case (which involved complex scientific judgments about future safety and policy). The High Court had focused on whether the 1977 Criteria were unreasonable or if there were serious flaws in the Prefectural Certification Council's process[cite: 1].

- Instead, the Supreme Court stated that the reviewing court itself must independently examine all circumstances and relevant evidence in light of empirical rules (experience-based principles)[cite: 1]. This includes considering the individual causal relationship between the applicant's specific symptoms and their exposure to the causative substance (methylmercury)[cite: 1].

- The court should then make its own individual and concrete determination as to whether the applicant indeed suffers or suffered from Minamata disease[cite: 1]. This effectively calls for a "substitution of judgment," where the court steps into the shoes of the administrative agency to make the factual determination.

- The comprehensive examination required for certification (and thus by the court) should include not only medical judgments about the patient's symptoms but also thorough consideration of the patient's history of exposure to the causative substance, their lifestyle, various epidemiological findings, and the results of relevant surveys[cite: 1].

4. The Status and Role of the "1977 Diagnostic Criteria"

The Court addressed the controversial 1977 Criteria:

- It acknowledged that the 1977 Criteria, which generally require a combination of symptoms for diagnosis, were established because individual symptoms often associated with Minamata disease can be non-specific on their own[cite: 1]. The criteria aimed to facilitate rapid and appropriate decisions for many applicants by creating a presumption of Minamata disease if the specified combination of symptoms was present, thereby negating the need for further proof of individual causation in such typical cases[cite: 1]. To this extent, the criteria possess a degree of rationality[cite: 1].

- However, the Court emphatically stated that the 1977 Criteria do not exclude the possibility of certifying an individual as having Minamata disease even if they do not meet the symptomatic combinations outlined therein[cite: 1].

- Certification is still possible if an individual causal link between the person's specific symptoms and methylmercury exposure can be established through a comprehensive review of all evidence and circumstances, based on empirical rules[cite: 1].

- The Court noted that the 1978 Vice-Minister's Notification, which explained that the 1977 Criteria were intended to concretize and clarify the earlier, more holistic 1971 Vice-Minister's Notification, supported this interpretation[cite: 1].

Key Takeaways and Analysis

This Supreme Court decision is a significant development in Japanese administrative law, particularly concerning pollution-related diseases and the judicial review of administrative actions involving scientific or medical fact-finding.

1. Shift in Judicial Review for Factual Medical Determinations:

The ruling clearly distinguishes administrative decisions based on the ascertainment of objective, past or present scientific or medical facts from those involving future predictions, policy judgments, or complex risk assessments. For the former, such as Minamata disease certification, the Court mandates a full, independent review by the judiciary, effectively a substitution of judgment. This contrasts sharply with the deferential approach taken in other contexts.

2. Explicit Distinction from "Scientific/Policy Discretion" Cases (like Ikata):

The Court directly addressed and rejected the analogy to the Ikata Nuclear Power Plant permit case[cite: 3]. The High Court had found parallels because both involved expert councils[cite: 3]. However, the Supreme Court emphasized that the Ikata case concerned judgments about future safety risks and policy decisions on acceptable levels of risk for nuclear power—matters inherently laden with uncertainty and policy considerations that warrant administrative discretion[cite: 3]. Minamata disease certification, by contrast, is about verifying an existing or past medical condition linked to a known historical exposure to a specific pollutant—a process of objective factual confirmation[cite: 3].

3. Prioritizing Individualized Justice and Substantive Truth:

The judgment underscores the importance of looking at the individual circumstances of each applicant. It signals that administrative convenience or rigid adherence to diagnostic guidelines (like the 1977 Criteria) should not prevent the recognition of genuine victims if a causal link to methylmercury exposure can be reasonably established through a comprehensive assessment of all available evidence, including exposure history and lifestyle factors, not just a narrow set of symptoms[cite: 3].

4. Reinterpreting the Role of Administrative Guidelines:

The decision clarifies that administrative guidelines, while potentially useful for efficiency (as the 1977 Criteria were for typical cases), cannot be applied in a way that legally bars the certification of individuals who fall outside their specific parameters but can otherwise demonstrate, through evidence, that they suffer from the disease as defined by its cause[cite: 1, 3]. The underlying purpose of the law—to provide relief to those affected by the specific pollution—must prevail.

5. Potential Impact on Victims' Relief:

By rejecting a narrow, discretion-based interpretation of the certification process and affirming that even individuals with atypical symptomologies (like sensory disturbances alone) could be certified if causation was proven, the Supreme Court's decision potentially paved the way for a broader scope of relief for many Minamata disease sufferers who had previously been denied official recognition[cite: 3]. It aligned the administrative certification pathway more closely with findings in some civil damages lawsuits where courts had already recognized a wider range of Minamata disease manifestations[cite: 3].

Conclusion

The 2013 Supreme Court ruling in the Minamata disease certification case marks a critical assertion of judicial oversight in administrative matters that turn on objective factual determinations, particularly in the context of public health and environmental pollution. By firmly rejecting the notion of administrative discretion in diagnosing Minamata disease and mandating a thorough, independent review by the courts, the decision champions a more substantive, evidence-based approach to justice for victims. It distinguishes such factual inquiries from policy-laden discretionary judgments, thereby refining the landscape of judicial review in Japanese administrative law and offering hope for a more comprehensive recognition of those affected by one of history's most devastating environmental disasters.