No Right to Hold On: When Post-Termination Expenses Don't Justify Retaining Property in Japan

Date of Judgment: July 16, 1971

Case Name: Claim for Vacant Possession of House, etc.

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

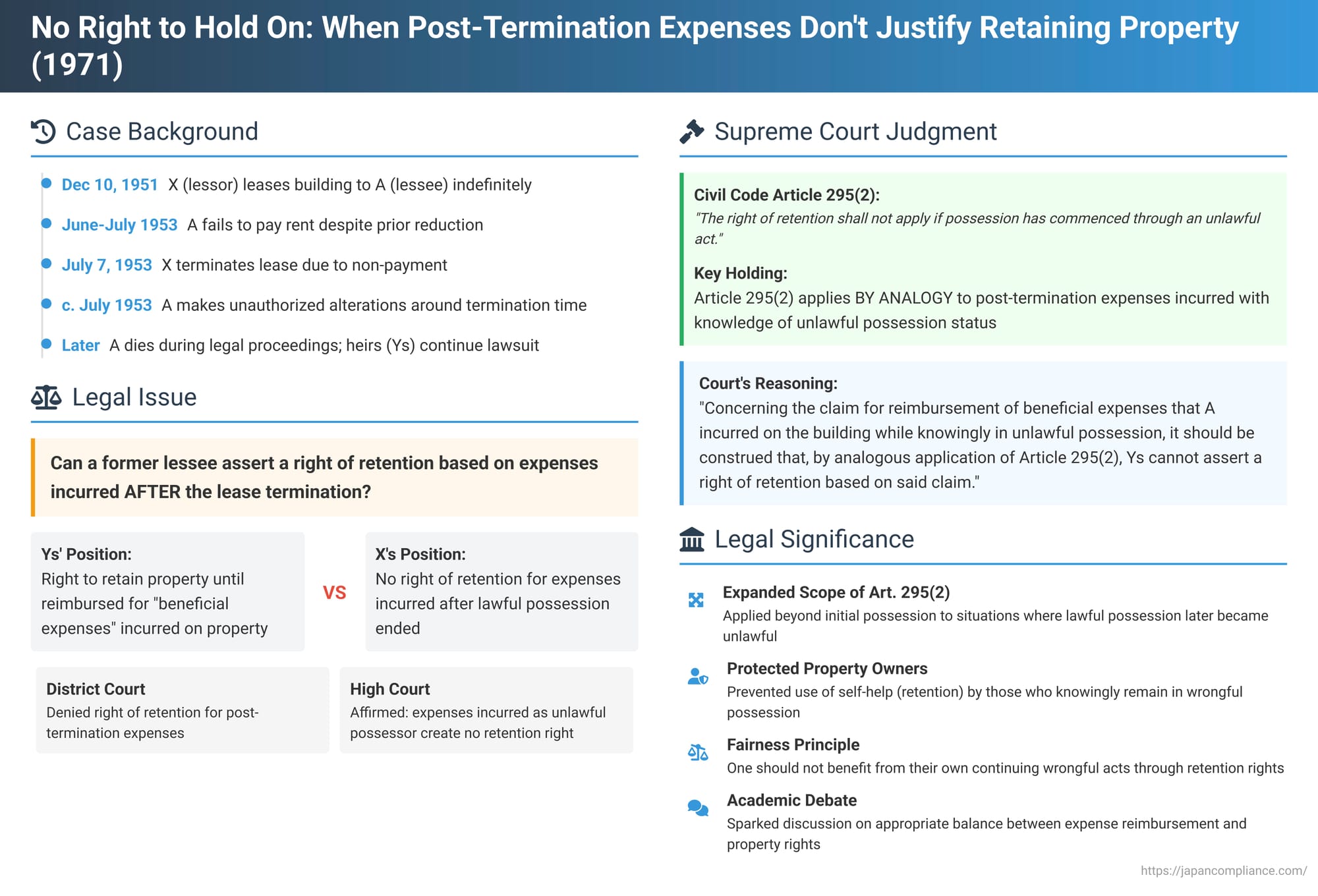

The Japanese Civil Code grants a possessor of another's property a "right of retention" (ryūchi-ken), allowing them to hold onto the property until a claim related to that property is satisfied[cite: 1]. This right is rooted in principles of fairness, preventing unjust enrichment and providing a form of security to the possessor[cite: 1]. However, this right is not absolute. Article 295, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code explicitly denies the right of retention if the possession itself began as a result of an unlawful act (fuhō kōi)[cite: 1]. A key question that has arisen is whether this statutory limitation can be extended by analogy to situations where possession was initially lawful but subsequently became unlawful, particularly if the possessor then incurs expenses on the property while knowingly in wrongful possession. The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this nuanced issue in a significant decision on July 16, 1971.

The Factual Scenario: A Lease Turns Sour

The case involved a dispute between a lessor, X, and the heirs of his former lessee.

- The Lease and Default: On December 10, 1951, X leased a wooden building he owned to A for an indefinite term[cite: 1]. At A's request, the rent was reduced starting from May 1953[cite: 1]. Despite this reduction, A failed to pay rent for June and July of 1953[cite: 1].

- Lease Termination: On June 29, 1953, X formally notified A, demanding payment of the overdue rent by July 2, 1953. This notice was received by A on June 30[cite: 1]. A did not pay the arrears within this period[cite: 1]. Consequently, on July 7, 1953, X sent A another notice, this time declaring the termination of the lease agreement due to the persistent non-payment of rent. A received this termination notice on July 8[cite: 1].

- Unauthorized Alterations: Around the time X served the notice of termination (both before and after its receipt), A undertook unauthorized extensions and alterations to the leased building[cite: 1].

- The Lawsuit and Succession: X initiated a lawsuit against A, seeking vacant possession of the building, payment of unpaid rent, and damages for the delay in vacating the premises[cite: 1]. During the course of the legal proceedings, A passed away. His heirs, Ys (the defendants/appellants), succeeded to his position in the lawsuit[cite: 1].

- Ys' Defense: Ys countered X's claims by asserting that they (as A's successors) held claims against X for necessary expenses (hitsuyōhi) and beneficial expenses (yūekihi) incurred on the property, as well as a right to demand that X purchase fixtures installed by A (zōsaku kaitori seikyūken)[cite: 1]. Based on these claims, Ys argued they were entitled to exercise a right of retention over the building until X satisfied these alleged debts[cite: 1].

The Legal Path: Lower Courts and the Supreme Court's Stance

The lower courts largely sided with the lessor, X.

- The District Court: This court upheld the validity of X's termination of the lease agreement[cite: 1]. It granted X's demand for possession and a portion of his claim for damages and unpaid rent[cite: 1]. Regarding Ys' counterclaims, the District Court found that a lessee cannot demand the purchase of fixtures if the lease was terminated due to the lessee's own default (such as rent non-payment)[cite: 1]. More critically for the right of retention issue, it determined that the beneficial expenses claimed by Ys were for work done after the lease had already been terminated[cite: 1]. Therefore, invoking Article 295, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code, the court denied Ys' assertion of a right of retention based on these post-termination expenses[cite: 1].

- The High Court: The High Court affirmed the District Court's judgment[cite: 1]. It specifically emphasized that the beneficial expenses were incurred after A had become an unlawful possessor due to the lease termination and, importantly, after A knew he was an unlawful possessor[cite: 1]. The High Court reasoned that, interpreting Article 295, Paragraph 2 based on the "principle of fairness," expenses incurred under such circumstances could not legitimately form the basis for a new right of retention over a property for which lawful possession had already ceased[cite: 1].

Ys then appealed to the Supreme Court, challenging the denial of their right of retention. The central issue was whether Article 295, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code could be applied by analogy to deny a right of retention for expenses incurred by a former lessee who continued to occupy the property and made improvements after the lease was validly terminated and after they became aware of their unlawful status as a possessor.

The Supreme Court's Ruling (July 16, 1971)

The Supreme Court dismissed Ys' appeal, upholding the lower courts' decisions.

- The Court first affirmed the High Court's factual finding that A, following the termination of the lease agreement, was indeed unlawfully possessing the building while knowing he no longer had any legal right to do so[cite: 1].

- On the main legal point, the Supreme Court held: "Concerning the claim for reimbursement of beneficial expenses that A incurred on the building under such circumstances, it should be construed that, by analogous application of Article 295, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code, Ys cannot assert a right of retention over the building based on said claim (referencing Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, March 3, 1966, Minshū Vol. 20, No. 3, p. 386)." [cite: 1]

- The Court concluded that the High Court's judgment on this point was correct[cite: 1]. It also dismissed Ys' arguments regarding a right of retention based on the fixture purchase claim as stemming from a misunderstanding of the High Court's decision[cite: 1].

Dissecting Civil Code Article 295 and the Right of Retention

To understand the Supreme Court's reasoning, it's essential to look at Article 295 of the Civil Code:

- Article 295, Paragraph 1: This paragraph establishes the general right of retention. It states that if a person possessing a thing belonging to another has a claim that has arisen "in respect of that thing" (meaning there's a connection, kenrensei, between the claim and the thing), and that claim is due, the possessor may retain the thing until the claim is satisfied[cite: 1]. This is fundamentally a rule of fairness, ensuring that someone who has, for example, repaired a watch can keep it until paid for the repair.

- Article 295, Paragraph 2: This paragraph provides a critical exception: "The provision of the preceding paragraph shall not apply if the possession has commenced through an unlawful act." [cite: 1] Thus, if someone steals a watch and then repairs it, they cannot claim a right of retention for the repair costs because their initial possession was unlawful. This exception, too, is grounded in fairness – one should not benefit from their own wrongdoing[cite: 1].

The Core Issue: Analogous Application of Article 295(2)

The literal wording of Article 295, Paragraph 2 refers to situations where possession commenced through an unlawful act[cite: 1]. The legal conundrum in this case, and similar ones, was what happens if possession began lawfully (e.g., under a valid lease) but subsequently became unlawful (e.g., after the lease was terminated), and the possessor then incurred expenses on the property with full knowledge of their unlawful status[cite: 1]? Could the principle behind Article 295, Paragraph 2 be applied by analogy?

The Supreme Court, in this 1971 decision, confirmed its affirmative stance on this question, following a line of precedents:

- Even before World War II, the Great Court of Cassation (Japan's then-highest court) had held that if expenses were incurred on a property after the possessor had lost their lawful right to possess it and knew this, an analogous application of Article 295, Paragraph 2 would deny a right of retention[cite: 1]. Examples include a case of lease termination for non-payment (Daishin'in, Dec. 23, 1921) and a seller retaining against a subsequent purchaser from their buyer (Daishin'in, May 30, 1931)[cite: 1].

- The post-war Supreme Court continued this trend. A notable case cited in the 1971 judgment was a decision from March 3, 1966, where a former buyer incurred expenses on a property after the sale contract had been rescinded by mutual agreement[cite: 1]. The Court held that if the former buyer knew they no longer had lawful possession, Article 295, Paragraph 2 applied by analogy to deny their right of retention[cite: 1].

This 1971 judgment solidified this analogical application specifically for scenarios involving former lessees who incur expenses after a valid lease termination, knowing their continued possession is unlawful[cite: 1].

Rationale and Fairness Considerations

The rationale for denying a right of retention in such "bad faith holding over" situations is rooted in fairness to the property owner[cite: 1]. Once a possessor's lawful right to occupy ceases (e.g., lease termination), they have a legal duty to promptly return the property to the owner[cite: 1]. To continue occupying the property knowingly without right, and then to incur expenses on it, can be seen as an act that is objectively wrongful towards the owner[cite: 1]. If the possessor is aware of their unlawful status (i.e., acts in bad faith), allowing them to then assert a right of retention based on these expenses would effectively allow them to leverage their continued wrongful occupancy against the owner, which is contrary to fairness[cite: 1]. The legal commentary suggests that the culpability of the possessor in these circumstances is a key factor[cite: 1].

It's important to note that this line of reasoning generally assumes that the act of incurring expenses itself, in the context of a known unlawful holding over, is not otherwise justified (e.g., as an emergency measure to preserve the property, which might fall under principles of negotiorum gestio or management of affairs without mandate, thereby negating the unlawfulness of the expense itself)[cite: 1]. The precedents focus on the possessor's bad faith or, in some later cases, even negligence concerning their lack of title, coupled with the objective wrongfulness of continuing to occupy and alter the property[cite: 1].

Academic Debate and Alternative Perspectives

The Supreme Court's stance on this issue has not been without academic debate[cite: 1].

- Some scholars, drawing on Article 196, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code (which allows even a bad-faith possessor to claim reimbursement for beneficial expenses, and permits a court to grant the owner a grace period for payment), argued that this provision implicitly presupposes the existence of a right of retention for such expenses unless a grace period is specifically granted[cite: 1]. On this view, even a possessor who knowingly or negligently holds over should be able to assert a right of retention[cite: 1]. The influential scholar Dr. W (Wagatsuma Sakae) largely supported this but proposed that retention should be denied by analogy to Article 295, Paragraph 2 only if the former lessee committed some form of "disloyal act" (fushin kōi) beyond merely holding over[cite: 1].

- Critics of this interpretation of Article 196(2) argue that it primarily addresses the existence and due date of the claim for expenses, which is a separate issue from whether a right of retention (a security right) should be granted for that claim under Article 295[cite: 1]. They also point out that, historically, the legislative development of these two articles does not suggest such a direct linkage[cite: 1].

- Even in more recent scholarship, some oppose the blanket denial of retention for bad-faith or negligent holdover possessors, arguing it places an undue risk of non-recovery of expenses on the possessor[cite: 1]. An alternative view suggests that retention should only be denied if the manner in which the possessor acquired the claim for expenses could itself be characterized as an unlawful act when viewed against prevailing commercial norms[cite: 1].

- Another perspective advocates for a more holistic balancing of various factors beyond just the possessor's subjective state of mind (bad faith or negligence) to determine the overall fairness of allowing or denying retention in a specific case[cite: 1].

However, the legal commentary provided suggests that the Supreme Court's position does not necessarily lead to unfairness[cite: 1]. The core idea of Article 295, Paragraph 2 is to deny retention when it would be inequitable due to the possessor's unlawful and culpable conduct[cite: 1]. This principle logically extends to a possessor who, knowing their right has ended, wrongfully continues possession and incurs expenses[cite: 1].

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision of July 16, 1971, reinforces a significant principle in Japanese property law: the limitation on the right of retention found in Article 295, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code can be applied by analogy. Specifically, a former possessor (like a lessee after lease termination) who incurs expenses on a property while knowing their continued possession is unlawful cannot typically assert a right of retention based on those expenses. This ruling underscores that the right of retention, while a vital mechanism for ensuring fairness, cannot be exploited to benefit from one's own continued wrongful actions against the rightful owner of the property. It maintains a balance by ensuring that the strong protection afforded by a right of retention is not available when its assertion would itself be contrary to equity.