Full Clawback for Hidden Earnings: Japan Supreme Court Interprets Public Assistance Act (2018)

Japan’s Supreme Court: welfare recipients who hide income must repay all unreported earnings under the Public Assistance Act—no basic deduction.

TL;DR

Japan’s Supreme Court ruled that welfare recipients who fail to report earned income must repay the entire unreported amount; the “basic deduction” applies only when income is properly disclosed.

Index

- The Factual Scenario: Unreported Income and the Basic Deduction Dispute

- The Legal Dispute and Lower Court Rulings

- The Supreme Court’s Decision: Upholding System Integrity

- Application to the Facts and Final Judgment

- Significance and Commentary

Japan's Public Assistance Act (Seikatsu Hogo Hō) provides a vital safety net, but its operation relies heavily on the principle of accurate disclosure by recipients. Article 61 of the Act explicitly obligates recipients to promptly report any changes in their income, expenditures, or other aspects of their livelihood. This reporting duty is fundamental, ensuring that assistance is calculated correctly based on actual need and that benefits supplement, rather than replace, resources recipients should be using for their own support.

Failure to comply with this duty, particularly through false applications or other fraudulent means leading to the improper receipt of benefits, triggers Article 78 of the Act. This provision empowers the government entity that disbursed the funds (typically the prefectural governor or municipal mayor) to collect back all or part of the improperly paid assistance costs from the recipient.

A significant question arises when unreported earned income is discovered: how should the amount to be clawed back under Article 78 be calculated? Specifically, should the calculation account for the "basic deduction" (kiso kōjo) – an amount normally disregarded from earned income when calculating benefits for those who do report properly? The basic deduction serves policy goals like incentivizing work and covering work-related costs. Does failing to report forfeit the right to have this deduction considered in the clawback calculation? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this precise issue in a judgment dated December 18, 2018.

The Factual Scenario: Unreported Income and the Basic Deduction Dispute

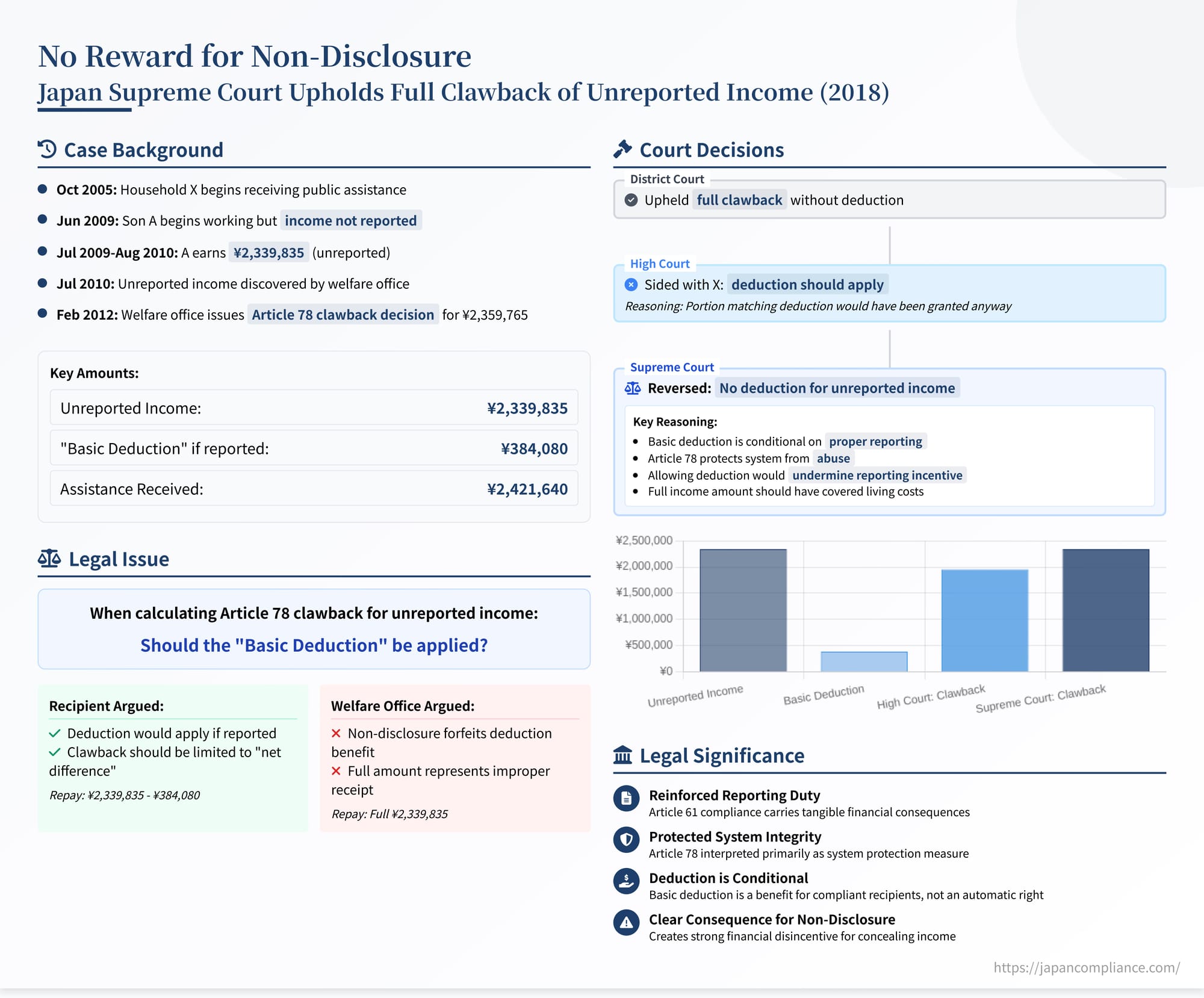

The case involved X, the head of a household receiving public assistance in Kadoma City (Y) since October 2005. The household included X's adult son, A. In June 2009, son A began working, receiving wages paid monthly in arrears. X was aware of A's employment but failed to report this income to the Kadoma City Welfare Office (headed by Director B, acting under delegated authority and thus the relevant administrative agency) as required by Article 61.

The unreported income was eventually discovered by the welfare office around July 2010 following an investigation into A's employment. It was determined that between July 2009 and August 2010, A had earned a total net income (after income tax withholding) of ¥2,339,835 ("Undeclared Earned Income"). Because this income went unreported, X's household continued to receive public assistance calculated as if the income did not exist. During this period, the household was paid a total of ¥2,421,640 in assistance benefits (covering livelihood, housing, and temporary needs).

In February 2012, the B Welfare Office Director issued a formal decision under Article 78 (the "Clawback Decision") demanding that X repay ¥2,359,765. This amount effectively included the entire sum equivalent to the Undeclared Earned Income of ¥2,339,835 (the small difference likely involved minor, unrelated adjustments not central to the core legal issue).

Crucially, in calculating this clawback amount, the welfare office did not apply the "basic deduction." The basic deduction is an established administrative practice, outlined in official guidelines (originating from a 1961 Vice-Minister's Notice). When earned income is properly reported, welfare offices deduct a certain amount – calculated based on income level, location, number of earners, etc. – before determining the income to be counted against the household's assistance needs. This deduction acknowledges increased living costs associated with working, helps maintain work incentives, and supports self-sufficiency. Had A's income been reported correctly during the relevant period, the corresponding basic deduction would have totaled ¥384,080 ("Applicable Basic Deduction Amount"). By including the full Undeclared Earned Income in the clawback calculation without subtracting this amount, the welfare office sought to recover funds equivalent to the entire unreported earnings.

The Legal Dispute and Lower Court Rulings

X challenged the Clawback Decision, arguing it was illegal to the extent it sought to recover the Applicable Basic Deduction Amount. X's position was that if the income had been reported, the basic deduction would have been applied, meaning assistance equivalent to that deduction amount would have been legitimately received. Therefore, under Article 78, the government should only be able to claw back the "net difference" – the amount of assistance received solely due to the failure to report (i.e., the assistance that replaced the income after the hypothetical deduction).

The lower courts reached different conclusions:

- District Court (Osaka): Dismissed X's claim, upholding the welfare office's calculation.

- High Court (Osaka): Partially ruled in favor of X. The High Court held that the Article 78 clawback should indeed be limited to the net difference between the assistance actually paid and the amount that would have been paid if the income (less the basic deduction) had been properly reported. It reasoned that the portion of assistance corresponding to the basic deduction was not received "improperly" or "fraudulently," as it would have been granted even with full disclosure. Thus, including the Applicable Basic Deduction Amount (¥384,080) in the clawback was illegal. The High Court ordered this portion of the Clawback Decision to be revoked.

The City (Y) appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Upholding System Integrity

The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision, siding with the welfare office on the central issue of the basic deduction.

Emphasis on Reporting Duty and Article 78's Purpose:

The Court began by reaffirming the foundational principles of the public assistance system: it operates based on need after recipients utilize their own resources (Articles 4(1), 8), and this necessitates prompt and accurate reporting of changes in circumstances, including income (Article 61).

The Court interpreted Article 78, the clawback provision, as having the primary purpose of protecting the public assistance system from abuse. When a recipient obtains benefits improperly by concealing income, Article 78 allows the government to recover the funds. The Court reasoned that the scope of this recovery should broadly encompass the portion of the concealed income that the recipient should have used to maintain their minimum standard of living instead of relying on assistance.

Distinguishing Earned Income from the Basic Deduction:

The Court drew a clear distinction between earned income itself and the basic deduction. Earned income, it stated, is inherently a resource that a recipient is expected to utilize for their own support. The basic deduction, conversely, is not an inherent right but an operational practice applied by the administration when earned income is properly reported. Its purpose is rooted in policy considerations – encouraging work and acknowledging work-related expenses.

No Deduction Entitlement Without Disclosure:

The crucial step in the Court's logic was connecting the basic deduction to the reporting requirement. Since the entire assistance system, including the application of deductions, relies on accurate information provided by the recipient, the Court concluded that a recipient who fails to fulfill their reporting duty regarding earned income cannot claim the benefit of the basic deduction when facing a clawback under Article 78.

To allow the deduction in cases of non-disclosure would undermine the purpose of Article 61 (the reporting duty) and Article 78 (preventing abuse). It would create a situation where failing to report income yields the same financial outcome (regarding the deducted amount) as reporting it properly, thus removing the incentive for compliance. The Court stated that allowing the recipient to retain the equivalent of the basic deduction in cases of improper receipt due to non-reporting is not required, and subjecting the full amount of unreported income (which should have covered living costs) to the Article 78 clawback is permissible and aligns with Article 78's objective of protecting the system's integrity.

The Ruling:

Therefore, the Supreme Court held that it is not illegal for a welfare office, when calculating the Article 78 clawback amount for benefits improperly received due to unreported earned income, to refuse to deduct the corresponding basic deduction amount.

Application to the Facts and Final Judgment

Applying this rule to X's case, the Court found:

- X failed to make proper reports regarding son A's earned income.

- As a result, X's household improperly received public assistance benefits.

- Consequently, the decision by the B Welfare Office Director not to subtract the Applicable Basic Deduction Amount (¥384,080) when calculating the Article 78 clawback amount was not illegal.

The Supreme Court concluded that the High Court's judgment contained a legal error that affected the outcome. It therefore modified the High Court judgment. While establishing the legality of not applying the basic deduction, the Court did slightly adjust the final clawback amount affirmed by the first instance court, limiting it to the actual total of the Undeclared Earned Income (¥2,339,835), effectively cancelling the minor excess in the original Clawback Decision (¥2,359,765). The core finding, however, was that requiring repayment equivalent to the full ¥2,339,835 without applying the basic deduction was lawful.

Significance and Commentary

This 2018 judgment provides significant clarification as the first Supreme Court ruling on the application of basic deductions within Article 78 clawback calculations. Its main implications are:

- Reinforcement of Reporting Duty: The decision places strong emphasis on the recipient's obligation under Article 61 to report income accurately and promptly. Failure to do so carries tangible consequences beyond merely repaying the net overpayment.

- System Integrity Prioritized: The Court interpreted Article 78 primarily as a tool to protect the welfare system from abuse, rather than purely as a mechanism analogous to civil unjust enrichment claims (which might focus only on the net benefit obtained).

- Basic Deduction is Conditional: The benefit of the basic deduction, designed to incentivize work and cover costs for those participating transparently in the system, is not extended to those who conceal income.

- Potential for Discretion? While ruling that not applying the deduction is legal, the judgment's language might implicitly leave room for administrative discretion. Some commentary suggests that in specific cases where non-reporting wasn't clearly abusive, or considering the recipient's hardship, the agency might still choose to apply the deduction, although the court found no such mitigating circumstances in this specific case.

It is also worth noting that Article 78 was amended in 2013 (after the facts of this case but before the final judgment) to allow authorities to add a penalty or surcharge of up to 40% to the clawback amount in certain cases, further strengthening the disincentives against fraudulent receipt of benefits.

In conclusion, this Supreme Court decision sends a clear message: adherence to reporting obligations is paramount in Japan's public assistance system. Recipients who fail to report earned income cannot expect to benefit from income disregards, such as the basic deduction, when the authorities later seek to recover improperly paid benefits under Article 78.

- Mapping the Limits of Transparency: Japan's Supreme Court on Disclosing Preliminary Dam Site Information

- Cross-Border Data Access & Platform Liability: Japan's Supreme Court Tackles Online Obscenity Case (2021)

- Challenging a Father's Name After Death: Japan's Supreme Court on Belated Paternity Invalidation Claims

- Public Assistance Act (English Translation) — Ministry of Justice