No Going Back: Japanese Supreme Court Rules on Tax Adjustments for Bankrupt Consumer Lender's Past Income in the Clavis Case

Date of Judgment: July 2, 2020

Case Name: Notice Disposition Cancellation, etc. Request Case (平成31年(行ヒ)第61号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

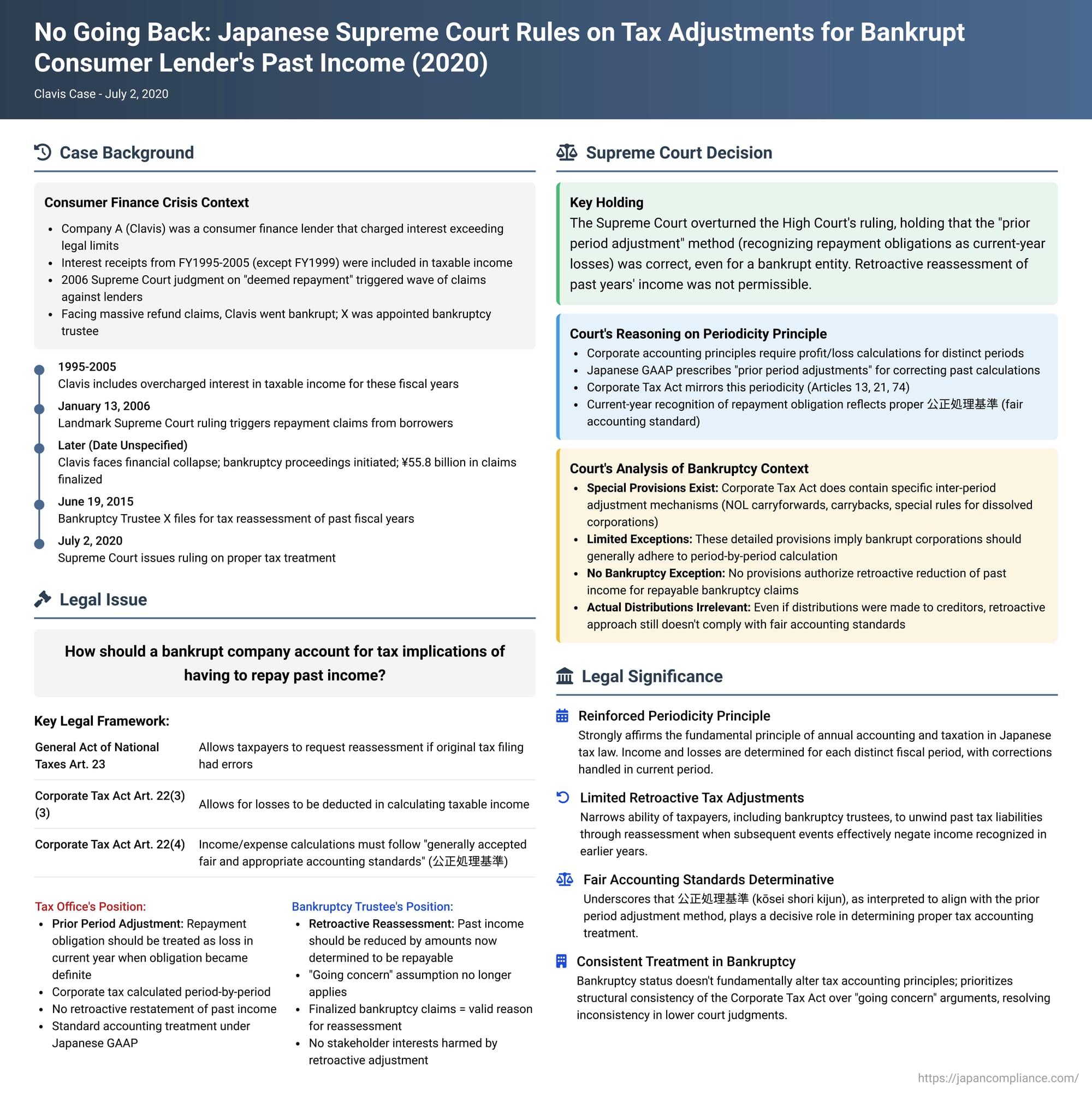

In a significant decision clarifying the principles of income allocation across fiscal years, particularly in the context of bankruptcy, the Supreme Court of Japan on July 2, 2020, ruled in what is commonly known as the Clavis case. The Court addressed whether a bankrupt consumer finance company, which had previously included overcharged interest in its taxable income, could later seek a retroactive reduction of that past income when the obligation to repay this interest became fixed. The Supreme Court held that the proper method was generally to treat the repayment obligation as a loss in the current period through a "prior period adjustment," rather than by retroactively amending past tax returns, even for an entity in bankruptcy.

The Consumer Finance Crisis and Its Tax Aftermath

The case involved Company A (formerly Clavis), a consumer finance lender. In its corporate tax returns for various fiscal years between FY1995 and FY2005 (excluding FY1999) ("the subject fiscal years"), Company A had received interest payments from borrowers that exceeded the limits prescribed by Japan's Interest Restriction Act. This excess interest was included in its taxable income for those respective years.

A pivotal Supreme Court judgment on January 13, 2006 (Minshu Vol. 60, No. 1, p. 1), which strictly interpreted the "deemed repayment" provisions of the Money Lending Business Act, triggered a massive wave of claims from borrowers for the repayment of such overcharged interest against many consumer finance companies, including Company A. Faced with these extensive repayment demands, Company A's financial situation deteriorated, ultimately leading to its bankruptcy. X was appointed as Company A's bankruptcy trustee.

In the course of Company A's bankruptcy proceedings, numerous claims for the return of overcharged interest (treated as claims for unjust enrichment) were filed by former borrowers. These claims, totaling over ¥55.8 billion (combining "Claim 1" of approximately ¥55.53 billion finalized after the general investigation period and "Claim 2" of approximately ¥0.30 billion finalized after a special investigation period), became finalized bankruptcy claims. The finalization of such claims in the schedule of bankruptcy creditors gives them the same legal effect as a final and binding court judgment (Bankruptcy Act, Article 124, paragraph 3). The bankruptcy trustee, X, subsequently made partial distributions to creditors on these finalized claims.

On June 19, 2015, X, acting as the bankruptcy trustee for Company A, filed requests for reassessment (更正の請求 - kōsei no seikyū) with the competent tax office for the subject fiscal years. X argued that the finalization of these overpayment repayment claims in the bankruptcy proceedings constituted a valid reason for reassessment under Article 23, paragraph 2, item 1 and paragraph 1, item 1 of the General Act of National Taxes. The trustee sought to retroactively reduce Company A's taxable income for those past years by the amount of the overcharged interest that was now confirmed as repayable.

The tax office head responded by issuing notices indicating no reason to make such reassessments. The tax office's position was that the obligation to repay the overcharged interest should be treated as a loss in the business year in which that obligation became definite (i.e., through the accounting process known as a "prior period adjustment" - 前期損益修正 zenki son'eki shūsei), rather than by retroactively altering the income calculations of past years.

The Legal Conundrum: Retroactive Correction or Current Year Loss?

The dispute presented two main approaches for addressing the tax implications of the subsequently confirmed repayment obligations:

- Retroactive Reassessment (Trustee X's argument): This approach would involve amending Company A's past tax returns for the subject fiscal years to exclude the overcharged interest from the income originally reported. This was based on the provisions for requesting a tax reassessment in the General Act of National Taxes (Article 23), which generally allow for corrections if the original tax declaration was not in accordance with tax laws or contained errors, resulting in an overpayment of tax.

- Prior Period Adjustment (Tax Office's argument): This method involves treating the obligation to repay the overcharged interest as a deductible loss in the current fiscal year—the year in which the obligation to repay became fixed (e.g., through the finalization of claims in the bankruptcy process). This aligns with the general principles of loss recognition under Article 22, paragraph 3, item 3 of the Corporate Tax Act and the overarching requirement in Article 22, paragraph 4 that income and expense calculations must adhere to "generally accepted fair and appropriate accounting standards" (公正処理基準 - kōsei shori kijun).

The first instance court (Osaka District Court) sided with the tax office, affirming that the prior period adjustment method was consistent with kōsei shori kijun. However, the Osaka High Court (the appellate court) reversed this decision, ruling in favor of the bankruptcy trustee. The High Court reasoned that kōsei shori kijun are not necessarily singular or monolithic. It emphasized that for a company in bankruptcy, the "going concern" assumption, which underpins many standard accounting principles like the typical prior period adjustment method, is no longer valid. Therefore, retroactively reducing past income for a bankrupt company would not undermine the basis for adjusting interests among stakeholders (like shareholders and creditors) and could be considered a fair and appropriate accounting treatment. The State (Y) then appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Prior Period Adjustment Prevails, Even in Bankruptcy

The Supreme Court overturned the Osaka High Court's judgment and ruled in favor of the State, concluding that the prior period adjustment method was the correct approach and that retroactive reassessment of past years' income was not permissible in this situation.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was grounded in the fundamental principles of both corporate accounting and corporate tax law in Japan:

- Primacy of Period-by-Period Calculation in Accounting and Tax:

- The Court noted that corporate accounting principles generally require profit and loss calculations to be made for distinct accounting periods. If a need arises to correct past profit/loss calculations, Japanese GAAP (specifically referencing the former "Accounting Principles for Business Enterprises" and the more current "Accounting Standard for Accounting Changes and Error Corrections" - ASBJ Statement No. 24) typically prescribes recording the necessary adjustment as a "prior period adjustment" (a special profit or loss item) in the current period when the need for correction is identified. These accounting standards are premised on the idea that corporate profit/loss is calculated for artificially demarcated periods (fiscal years) reflecting ongoing economic activity, and they do not generally anticipate retroactive restatement of past financial statements for such subsequent events.

- The Corporate Tax Act mirrors this periodicity. It mandates taxation based on income calculated for each business year (Article 13, Article 21) and requires tax returns to be filed based on finalized financial statements for that year (Article 74, paragraph 1). Tax liability is generally fixed upon filing the return for that specific period.

- Application to Overcharged Interest Repayment:

- Following these principles, when a moneylending corporation receives interest, correctly includes it in its income for tax declaration purposes, and it is later determined (e.g., due to the Interest Restriction Act) that this interest was excessive and constitutes unjust enrichment that must be repaid, the accounting treatment consistent with kōsei shori kijun is to recognize this repayment obligation as a loss in the fiscal year in which this obligation becomes definite. This is the essence of the "prior period adjustment" method.

- Treatment of Bankrupt Corporations:

- The Supreme Court acknowledged that the Corporate Tax Act does contain specific provisions that allow for inter-period adjustments to taxable income, such as the carryforward of net operating losses (Article 57), the carryback of NOLs for refund (Article 80), and special rules for dissolved corporations, like the deduction of certain expired NOLs if no residual assets are expected (Article 59, paragraph 3).

- The Court emphasized that these special provisions, with their detailed requirements and procedures, are also applicable to corporations in bankruptcy. The existence of these specific, carefully defined exceptions implies that the general legislative intent is for bankrupt corporations, too, to adhere to the principle of period-by-period income calculation, with inter-period adjustments (like retroactive changes) being permissible only under these explicitly stipulated conditions.

- Critically, the Court found no special provisions in the Corporate Tax Act or related tax laws that would authorize a different treatment—specifically, a retroactive reduction of past income—for a bankrupt corporation in a situation where previously reported interest income is later confirmed as a repayable bankruptcy claim. It also noted that there was no established accounting practice under Japanese GAAP that would treat such a situation by retroactively reducing prior years' income.

- This holds true, the Court stated, even if some distributions (repayments) on these unjust enrichment claims have actually been made from the bankruptcy estate to the creditors, or even if the bankrupt company itself had, for some reason, purported to retroactively restate its past financial statements.

- Conclusion on Conformity with Kōsei Shori Kijun:

- Based on the above, the Supreme Court concluded that attempting to retroactively reduce the taxable income of the subject fiscal years (when the interest was originally received) does not conform to kōsei shori kijun, irrespective of whether distributions on the claims were made.

- Consequently, Trustee X's requests for reassessment, which were premised on such a retroactive income reduction, did not satisfy the requirements of Article 23, paragraph 1, item 1 of the General Act of National Taxes (which permits a reassessment request if the original tax declaration did not comply with tax laws or contained errors, leading to an overpayment of tax).

Key Implications and Analysis

The Supreme Court's decision in the Clavis case carries significant weight:

- Reinforcement of the Periodicity Principle in Taxation: The judgment strongly affirms the fundamental principle of annual accounting and taxation in Japanese corporate tax law. It establishes that income and losses are to be determined for each distinct fiscal period, and corrections related to prior periods are generally to be handled within the current period when the correcting event occurs, even for entities in bankruptcy, unless specific statutory provisions expressly allow for a different (e.g., retroactive) treatment.

- Limited Scope for Retroactive Tax Adjustments: The ruling significantly narrows the perceived ability of taxpayers, including bankruptcy trustees, to unwind past tax liabilities through requests for reassessment when subsequent events effectively negate income recognized in earlier years. The preferred route for tax relief in such situations is generally through deductions in the current period when the loss or obligation is finalized.

- The Role of "Fair and Appropriate Accounting Standards" (Kōsei Shori Kijun): The decision underscores that kōsei shori kijun, as interpreted by the Court to align with the prior period adjustment method, play a decisive role in determining the proper tax accounting treatment for such corrections.

- The "Going Concern" Argument in Bankruptcy: The Supreme Court did not explicitly adopt or endorse the High Court's line of reasoning that the inapplicability of the "going concern" accounting assumption to bankrupt companies justifies a departure from the standard prior period adjustment method for tax purposes. Instead, it prioritized the structural consistency and specific provisions of the Corporate Tax Act, which already provide certain exceptional inter-period adjustment mechanisms applicable to bankrupt entities. Legal commentary suggests the Supreme Court, by focusing on the inherent structure of the Corporate Tax Act and its defined exceptions, resolved the inconsistency seen in lower court judgments regarding this issue.

- Potential for Unresolved Tax Burdens ("Taxation Without Income"): Legal commentators have noted that strictly adhering to the prior period adjustment method can, in some situations (particularly in bankruptcy where the entity may have no current income or future prospects to absorb such losses), lead to a situation where tax paid on income in prior years effectively remains with the government even though the economic benefit of that income has been subsequently lost. This has led to discussions about whether alternative legal remedies, such as claims for unjust enrichment against the State, might be theoretically available to address such perceived inequities, though the Supreme Court did not delve into this aspect in its judgment.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment in the Clavis case provides a definitive clarification on the tax treatment of income recognized in prior periods that subsequently becomes repayable due to events like the finalization of unjust enrichment claims in bankruptcy. By affirming the primacy of the "prior period adjustment" method—treating the repayment obligation as a loss in the current period—even for bankrupt entities, the Court reinforced the fundamental principle of period-by-period tax accounting in Japan. This decision emphasizes that retroactive amendments to past tax liabilities are generally not permitted unless specifically authorized by an explicit provision in the tax law, thereby upholding the structural integrity and predictability of the corporate tax system.