No Exclusive Rights to Racehorse Names: Japan's Supreme Court Rejects 'Publicity Rights for Things' in Gallop Racer Case

Judgment Date: February 13, 2004

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Case Numbers: Heisei 13 (Ju) No. 866 & No. 867 (Claim for Injunction Against Production and Sale, etc.)

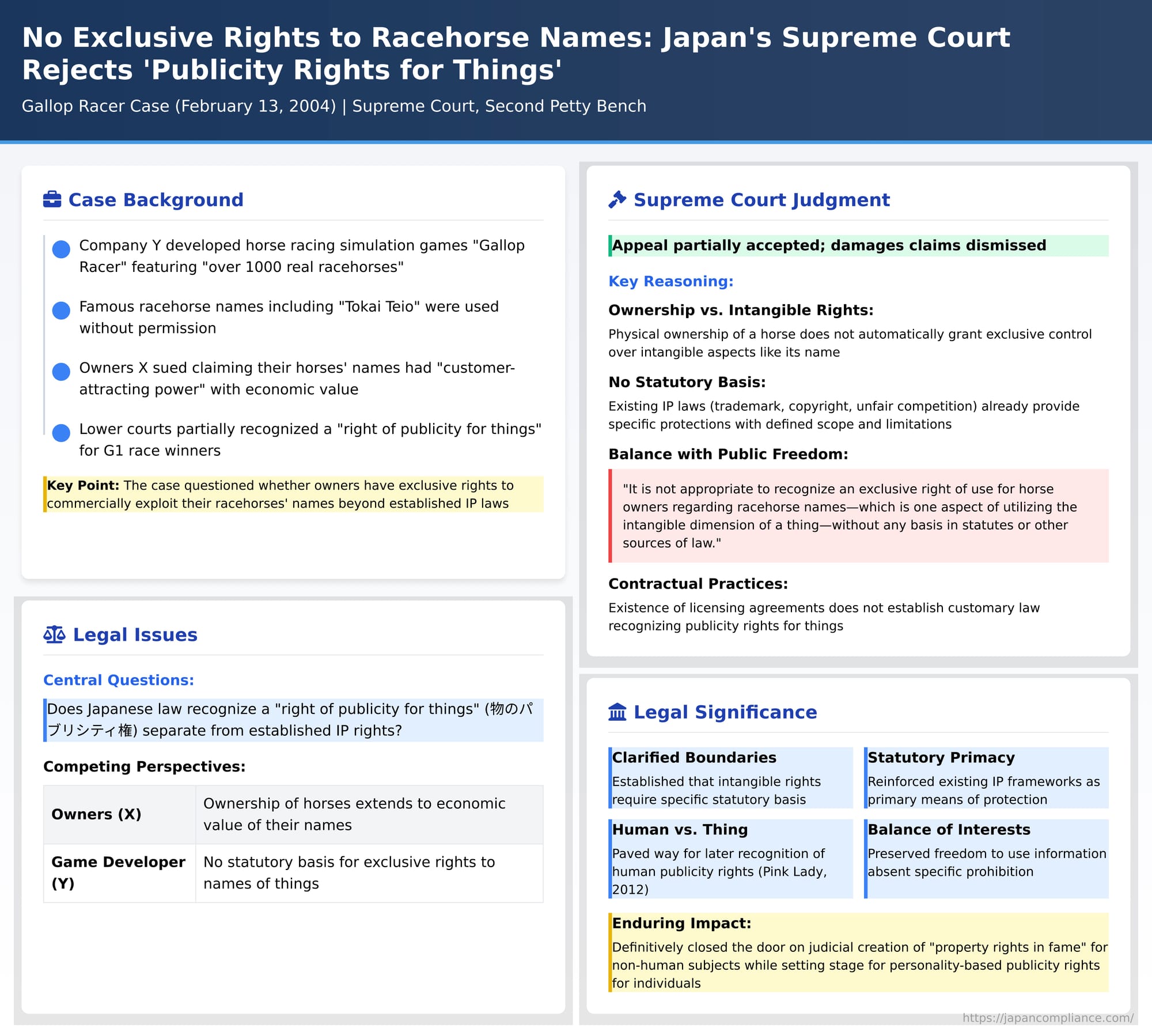

The "Gallop Racer" case (ギャロップレーサー事件), decided by the Japanese Supreme Court in 2004, is a landmark judgment that squarely addressed the question of whether a "right of publicity for things" (物のパブリシティ権 - mono no paburishiti-ken) exists under Japanese law. Specifically, it examined whether owners of famous racehorses possess an inherent, exclusive right to control the commercial use of their horses' names, particularly in contexts like video games, even in the absence of protection under established intellectual property statutes such as trademark or copyright law. The Supreme Court's definitive rejection of such a right has had significant implications for how intangible values associated with objects and animals are treated in Japan.

The Gallop Racer Game and the Horse Owners' Claims

The dispute centered around a series of popular horse racing simulation video games.

- The Defendant (Company Y): Company Y, the appellant before the Supreme Court, was a video game developer and publisher. It produced and sold horse racing simulation games titled "Gallop Racer" and "Gallop Racer 2."

- The Games' Content: These games allowed players to assume the role of jockeys, select from a roster of registered racehorses, and compete in virtual races on tracks designed to mimic real-life racecourses. A key feature, highlighted on the game packaging and in promotional materials, was the inclusion of "over 1000 real racehorses." Famous racehorses, including the renowned "Tokai Teio," were specifically mentioned as being among the selectable horses in the games.

- The Plaintiffs (X): The plaintiffs, X (appellees before the Supreme Court), were a group of individuals who either currently owned or had previously owned the famous racehorses whose names were used in Company Y's video games. This use was made without the permission of these horse owners.

- The Legal Claim: X sued Company Y, asserting that the names of their celebrated racehorses possessed significant "customer-attracting power" (顧客吸引力 - kokyaku kyūinryoku) and thereby held substantial economic value. They argued that, as owners of the horses, they possessed an exclusive, proprietary right (which they termed a "right of publicity for things") to control and commercially exploit this economic value. They claimed that Company Y's unauthorized use of the horse names in the "Gallop Racer" games infringed this right, and they sought an injunction to stop the production and sale of the games, as well as monetary damages.

Lower Court Rulings: Tentative Recognition of "Publicity Rights for Things"

The lower courts had shown some willingness to recognize the plaintiffs' claims, albeit with variations:

- First Instance (Nagoya District Court): The District Court acknowledged the concept of a "right of publicity for things." It found that racehorses that had competed in prestigious "G1 races" generally possessed customer-attracting power. Based on this, the court ruled in favor of some of the plaintiff horse owners, finding that their publicity rights had been infringed and awarded them damages.

- Second Instance (Nagoya High Court): The High Court upheld the general concept, referring to the right as a "broad-sense right of publicity" encompassing the economic value of information like the names of things. However, it narrowed the scope, finding that only racehorses that had actually won "G1 races" possessed the requisite customer-attracting power to trigger such a right. Nevertheless, it still found infringement for some of the plaintiffs and upheld damage awards.

Both Company Y (the game developer) and the group of horse owners X (regarding the scope of recognized rights and remedies) sought and were granted leave to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Rejection of a General "Publicity Right for Things"

The Supreme Court issued a decisive judgment, partially overturning the High Court's decision (specifically, it reversed the part that had found Company Y liable for damages and dismissed those claims by the horse owners). While it upheld the High Court's dismissal of the injunction claim (on the grounds that even if such a right existed, it wouldn't necessarily support an injunction in this developing area of law), its core reasoning dismantled the notion of a general, non-statutory "right of publicity for things."

The Supreme Court's reasoning was multi-faceted:

I. Ownership of a Physical Object vs. Control Over Its Intangible Aspects:

The Court began by drawing a fundamental distinction between the tangible and intangible aspects of property.

- Ownership of a Thing (e.g., a Racehorse): The right of ownership (所有権 - shoyūken) over a physical object like a racehorse grants the owner exclusive control over the tangible, corporeal aspect of that object.

- No Automatic Control Over Intangible Aspects (e.g., its Name): This ownership of the physical object does not, in itself, extend to an inherent, exclusive right to directly control the intangible aspects associated with that object, such as its name. The name of a horse is an intangible attribute.

- No Infringement of Physical Property Rights: Therefore, the Court reasoned, if a third party (like Company Y) uses a racehorse's name—an intangible aspect—without interfering with the owner's physical control over the actual horse (the tangible object), such use does not infringe the owner's property rights in the horse itself. For this point, the Supreme Court referenced its earlier decision in the Gankinkei case (Supreme Court, 1984), which concerned the ownership of a valuable piece of ancient calligraphy versus the separate copyright in the calligraphic work as a literary creation. The principle was similar: owning the physical manuscript didn't automatically grant all rights to its intangible content.

II. No General Exclusive Right to Commercially Use Names of Things Based Solely on Customer Appeal, Absent Statutory Basis:

This was the crux of the Court's decision regarding the "right of publicity for things."

- Existing Intellectual Property Laws Provide Specific Protections: The Court pointed out that Japanese law already has a well-developed framework of intellectual property statutes—such as the Trademark Law (商標法 - Shōhyōhō), Copyright Law (著作権法 - Chosakukenhō), and Unfair Competition Prevention Act (不正競争防止法 - Fusei Kyōsō Bōshi Hō). These laws grant exclusive rights for certain uses of intangible creations or indications (like names, artistic works, or marks of trade) to specific persons, but only when specific statutory requirements are met (e.g., registration for trademarks, originality for copyright, well-knownness and likelihood of confusion for unfair competition).

- Balancing Protection with Public Freedom: These existing IP laws, while providing protection, also carefully define the scope, content, duration, and limitations of the exclusive rights they grant. This detailed legislative framework is designed to ensure that the grant of exclusive rights does not unduly restrict the freedom of others in their economic and cultural activities.

- No Justification for a New, Non-Statutory Exclusive Right for Names of Things: In light of this existing, carefully balanced statutory regime, the Supreme Court stated: "Even if the names of racehorses possess customer-attracting power, it is not appropriate to recognize an exclusive right of use, etc., for horse owners regarding the use of racehorse names—which is one aspect of utilizing the intangible dimension of a thing—without any basis in statutes or other sources of law."

- No Tort Liability for Unauthorized Use of Names of Things Under Current Law: The Court further concluded that, for an unauthorized use of a racehorse's name to be deemed a tort (不法行為 - fuhō kōi), the "scope and manner of acts that would be considered unlawful would need to be clearly defined by statutes or other sources of law." It found that, "at the present time, this is not the case." Therefore, such use "cannot be affirmed as constituting a tort."

- Conclusion on Claims: Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court held that the horse owners' claims for an injunction or for damages based on an alleged "right of publicity for things" could not be upheld.

III. Contractual Practices Do Not Create a Customary Law Right:

The Court also addressed the evidence presented by the lower courts that some horse owners had indeed entered into contracts and received license fees for the use of their horses' names in games or other commercial ventures.

- The Supreme Court acknowledged that such contractual agreements exist. However, it noted that parties might enter into such licensing agreements for various practical reasons, such as a desire to avoid potential disputes or to ensure the smooth execution of their business projects, rather than because of a universally recognized legal obligation.

- Consequently, the mere existence of these private contractual arrangements "does not suffice to conclude that a social custom or customary law exists which recognizes that horse owners have an exclusive right to utilize the economic value possessed by their racehorses' names."

The Legal Landscape: Why No General "Publicity Right for Things"?

The Gallop Racer judgment firmly established that, in Japan, there is no general, non-statutory "right of publicity" that attaches to inanimate objects or animals, even if their names or images have acquired significant customer-attracting power.

- Emphasis on Statutory Basis for Exclusive Rights: The decision underscores a fundamental principle in Japanese (and many other civil law) jurisdictions: exclusive rights, especially those that restrict the freedom of others to use information or intangible assets, generally require a clear basis in enacted statutes. Courts are typically reluctant to create new categories of exclusive property rights through judicial pronouncements alone, particularly in areas already extensively regulated by intellectual property legislation.

- The Role of Existing IP Regimes: The Supreme Court's reasoning highlights that the existing intellectual property framework (trademarks, copyrights, unfair competition law) is considered the primary means for protecting intangible values. If a racehorse's name is used as a trademark for certain goods/services and is registered, it receives trademark protection. If its image is an original artistic work, it might receive copyright protection. If its name becomes a well-known indicator of a particular business and is used by another in a confusing way, the UCPA might offer remedies. The Court implied that if these specific statutory conditions are not met, a fallback to a general "publicity right for the thing itself" is not available.

- Balancing Interests: The judgment reflects a concern for balancing the protection of any commercial value associated with such "things" against the broader public interest in allowing the free use of names and information for economic and cultural activities, unless such use falls foul of a specific legal prohibition. Creating an overly broad "publicity right for things" could unduly restrict creative works (like games, books, films that refer to real-world objects or animals) and other commercial activities.

Impact on the Development of the (Human) Right of Publicity

The timing of the Gallop Racer decision is noteworthy in the broader context of the development of publicity rights in Japan.

- As detailed in the PDF commentary , this ruling in 2004, which denied a publicity right for things, actually preceded the landmark "Pink Lady case" (Supreme Court, 2012), which affirmed and defined the right of publicity for persons based on personality rights .

- In the early 2000s, the legal nature of the (human) right of publicity was still being actively debated in Japan, with some lower courts leaning towards a property rights rationale and others towards a personality rights rationale. The lower courts in Gallop Racer had attempted to extend a property-like concept of publicity rights to the racehorses.

- Simultaneously, other lower court cases involving racehorse names (specifically, the "Derby Stallion" game series) had shown skepticism towards a "publicity right for things," often because the prevailing arguments for human publicity rights were increasingly rooted in personality rights—a concept not directly applicable to animals or inanimate objects .

- The Supreme Court's decisive rejection of a "publicity right for things" in Gallop Racer (and its same-day decision not to accept the appeal in a Derby Stallion case) effectively closed the door on the judicial creation of such a broad, non-statutory right for non-human subjects .

- This, in turn, may have helped pave the way for the subsequent Pink Lady decision. By clearly distinguishing "things" from "persons," the Gallop Racer ruling arguably allowed the Supreme Court in Pink Lady to more confidently ground the human right of publicity in the well-established concept of personality rights, rather than venturing into more contentious property-based theories for intangibles lacking specific statutory recognition .

Lingering Questions and Future Considerations

While Gallop Racer firmly rejected a general "publicity right for things" based on their names, the PDF commentary raises a few nuanced points for ongoing consideration:

- Unauthorized Use of Images of Things: The Gallop Racer judgment focused on the "unauthorized use of racehorse names," stating that the scope of unlawful acts was not clearly defined by law for such use. The commentary questions whether this logic would automatically and entirely preclude tort liability for the unauthorized commercial use of images of things in all circumstances, especially if such use might infringe other legally protected interests not explicitly covered by existing IP statutes . However, it also notes that lower courts have generally been hesitant to find tort liability for the use of non-copyrightable works following another Supreme Court decision concerning North Korean films .

- When Can a "Thing" Be a Symbol of a Person's Identity? Even if things themselves don't have publicity rights, the question arises whether an image or name of a thing can become so inextricably linked to a person's identity that its use could infringe that person's (human) right of publicity. The Pink Lady case defined the subject of human publicity rights as "a person's name, portrait, etc.," linking it to "the symbol of an individual's personality."

Conclusion

The Gallop Racer Supreme Court decision delivered a clear and unequivocal message: under current Japanese law, there is no general, non-statutory "right of publicity for things" that grants owners an exclusive right to control the commercial use of the names of those things, even if they possess significant customer-attracting power. The protection of intangible values associated with objects or animals must be sought within the established frameworks of specific intellectual property statutes like Trademark Law, Copyright Law, or the Unfair Competition Prevention Act. This judgment reinforces the principle that the creation of new categories of exclusive intangible rights typically requires legislative action rather than judicial innovation, thereby preserving a balance between protecting commercial value and maintaining public freedom to engage in economic and cultural activities. While it closed the door on a broad "publicity right for things," it also played a role in shaping the subsequent development and clarification of the distinct, personality-based right of publicity for human individuals in Japan.