No Easy Revival: Statutory Superficies for Rebuilt Buildings After Joint Mortgage in Japan

Date of Judgment: February 14, 1997

Case Name: Action for Termination of Short-Term Lease, etc.

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

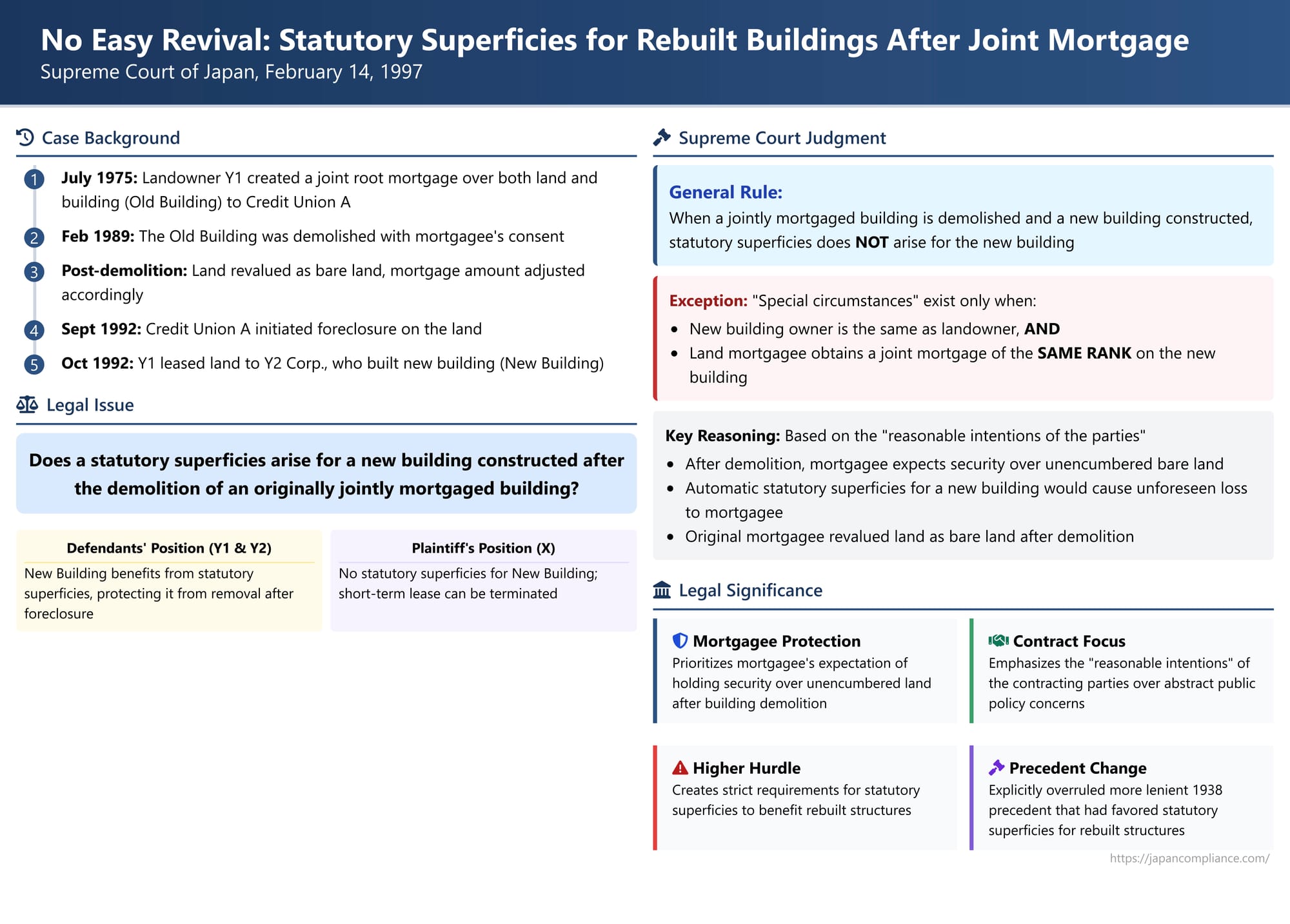

The Japanese legal concept of "statutory superficies" (hōtei chijōken), provided under Article 388 of the Civil Code, serves a crucial function: it grants a building owner the right to continue using the land on which their building stands, even if the land is sold to a new owner through a mortgage foreclosure, provided certain conditions are met. A primary condition is that the land and the building must have been owned by the same person at the time the mortgage was created. This aims to prevent the often economically wasteful demolition of perfectly sound buildings. However, what happens if a building that was originally part of a joint mortgage with the land is demolished, and a new building is subsequently constructed on that land? Does this new building automatically benefit from a statutory superficies if the land mortgage is later foreclosed? The Supreme Court of Japan tackled this complex issue in a significant judgment on February 14, 1997.

The Factual Background: A Joint Mortgage, Demolition, Rebuilding, and Foreclosure

The case involved a series of transactions concerning a piece of land ("the Land") owned by Y1:

- The Joint Root Mortgage: In July 1975, Y1 granted A Credit Union a joint root mortgage (kyōdō neteitōken). This mortgage covered both the Land owned by Y1 and a building then existing on it ("Old Building"), also owned by Y1. (A root mortgage secures a fluctuating range of debts up to a predetermined maximum amount).

- Demolition of the Old Building: Subsequently, Y1, with the consent of A Credit Union (the mortgagee), demolished the Old Building. The demolition was officially registered on February 13, 1989.

- Land Revaluation and Mortgage Adjustment: After the demolition, A Credit Union reassessed the Land's collateral value as bare land (land without a building). Based on this revaluation, the maximum amount (credit limit) secured by the root mortgage on the Land was incrementally increased on several occasions.

- Foreclosure and Assignment of Mortgage: In September 1992, A Credit Union initiated compulsory auction proceedings against the Land based on its root mortgage. An attachment registration was made on September 18, 1992. Later, X Credit Union acquired the root mortgage and the secured claims from A Credit Union by assignment. X Credit Union also succeeded to A Credit Union's position as the foreclosing creditor in the ongoing auction proceedings for the Land.

- Lease and Construction of New Building: In the interim, Y1 leased the Land to Y2 Corp. This lease was characterized as a "short-term lease" (tanki chinshakuken), a type of lease which, under the Civil Code provisions existing before amendments in 2003 (old Article 395), could sometimes survive a mortgage foreclosure for a limited period. On October 16, 1992, Y2 Corp. constructed a new building ("New Building") on the leased Land.

- The Lawsuit: X Credit Union filed a lawsuit against Y1 (the landowner) and Y2 Corp. (the lessee and owner of the New Building). Among other claims, X Credit Union sought the termination of Y2 Corp.'s short-term lease, invoking a provision in the old Civil Code (Article 395 proviso) that allowed a mortgagee to terminate such leases if they were detrimental to the mortgage. The District Court granted this request.

- The Statutory Superficies Defense: In the High Court, Y1 and Y2 Corp. introduced a crucial new defense: they argued that a statutory superficies had arisen for the New Building on the Land. If this were true, X Credit Union's mortgage on the Land would only cover the Land as already burdened by this statutory right of use for the New Building. Consequently, Y2 Corp.'s lease of this (already burdened) land would not cause any actual damage or loss to X Credit Union's security interest. The High Court, however, rejected this argument and dismissed their appeal. Y1 and Y2 Corp. then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Question: Does Statutory Superficies Attach to the New Building?

The central issue for the Supreme Court was whether a statutory superficies could arise for the New Building under these circumstances. Specifically, if land and an existing building are jointly mortgaged, the original building is then demolished, and a new building is later constructed on the (now technically bare, but still mortgaged) land, does this new building gain the protection of a statutory superficies if the land mortgage is subsequently foreclosed?

The Supreme Court's Ruling (February 14, 1997): Generally, No Statutory Superficies for Rebuilt Structures

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by Y1 and Y2 Corp., holding that, as a general rule, a statutory superficies does not arise for a new building constructed after the demolition of an originally jointly mortgaged building.

- The General Rule: The Court stated: "When a landowner has created a joint mortgage over both their land and the building situated thereon, and that building is subsequently demolished, and a new building is thereafter constructed on the said land, it is reasonable to construe that a statutory superficies does not arise for the new building, unless there are special circumstances."

- The "Special Circumstances" Exception: The Court elaborated on what might constitute such "special circumstances" that would allow a statutory superficies for the new building: "such as when the owner of the new building is the same as the owner of the land, AND the mortgagee of the land, at the time the new building was constructed, also obtained a joint mortgage of the same rank on the new building."

- Rationale for the General Rule (Denial of Superficies for Rebuilt Structure):

- Mortgagee's Initial Security: When a joint mortgage is initially created over both land and an existing building, the mortgagee secures the combined collateral value of both properties. The mortgagee accepts that a statutory superficies would arise for that specific, originally mortgaged building if, for example, only the land or only the building were to be sold separately as a result of foreclosure.

- Expectation Upon Demolition: However, if the originally mortgaged building is demolished, the reasonable expectation of the land mortgagee shifts. They now anticipate holding security over the land as unencumbered bare land, free from any statutory superficies that might have been associated with the demolished building or that might arise for a different, new building. This, the Court reasoned, reflects the "reasonable intentions" of the parties involved in the mortgage agreement.

- Unforeseen Loss to Mortgagee: To allow a statutory superficies to automatically arise for a new building (which was not itself subject to the original joint mortgage, or any equivalent new mortgage) would mean that the land mortgagee, who initially secured the value of the land (potentially as bare land post-demolition), would suddenly find their security interest diminished to the value of land already burdened by a statutory superficies for this new structure. The Court viewed this as an unforeseen loss to the mortgagee, contrary to the parties' reasonable intentions at the time the security was established or subsequently managed (especially when, as in this case, the land was revalued as bare land after demolition).

- Public Interest in Preserving Buildings vs. Parties' Intentions: The Court acknowledged that its ruling (denying statutory superficies for the new building) might, in some instances, lead to outcomes that conflict with the general public interest in preserving buildings. However, it concluded that "the public interest in protecting buildings should not be prioritized to the extent of contravening the reasonable intentions of the mortgaging parties."

- Overruling a Prior Precedent: The Supreme Court explicitly stated that a previous Great Court of Cassation judgment (Daishin'in, May 25, 1938, Minshū Vol. 17, No. 12, p. 1100), to the extent that it was inconsistent with this new ruling, should be considered changed. The 1938 precedent had been more lenient in finding a statutory superficies for a rebuilt structure, suggesting that even if a jointly mortgaged building burned down and a new one was built (e.g., by the landowner's wife), a statutory superficies with content similar to what the old building would have had would still be deemed created by the mortgagor.

- Application to the Facts of This Case:

- Y1 (the landowner) had initially granted A Credit Union a joint root mortgage over the Land and the Old Building.

- The Old Building was subsequently demolished.

- Y2 Corp. (Y1's lessee) later constructed the New Building on the Land.

- The "special circumstances" exception did not apply here because the New Building was not mortgaged to X Credit Union (the successor mortgagee of the land) with a mortgage of the same rank as the land mortgage.

- Furthermore, the Court noted that after the Old Building was demolished, Y1 (the landowner) and A Credit Union (the original mortgagee) had, on multiple occasions, re-evaluated the Land as bare land for collateral purposes and had adjusted the maximum amount secured by the root mortgage accordingly. This course of conduct strongly indicated that the parties themselves did not intend for a statutory superficies to automatically arise for any subsequently constructed new building.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that no statutory superficies arose for the New Building, and the High Court's decision to this effect was correct.

The "Reasonable Intentions" of the Parties

A key element in the Supreme Court's reasoning is the "reasonable intentions of the mortgaging parties." When a building that was part of a joint mortgage is demolished, the Court presumes that the land mortgagee thereafter expects to hold security over the land in its unburdened, bare state. This expectation is deemed reasonable and forms the basis for denying an automatic statutory superficies for any new structure built later, unless the mortgagee explicitly agrees to a new arrangement that includes security over the new building. The fact that in this case the land was revalued as bare land by the original mortgagee after the demolition of the Old Building, and the mortgage terms were adjusted, lent strong factual support to this interpretation of the parties' intentions.

The Strict "Special Circumstances" Exception

The judgment provides a very narrow gateway for a statutory superficies to arise for a rebuilt structure: the owner of the new building must be the same as the landowner, and the land mortgagee must, at the time of the new building's construction, also secure a new joint mortgage of the same rank on that new building.

- This exception essentially requires the parties to recreate the original security position for the mortgagee, ensuring that the mortgagee once again has security over both the land and the (new) building as an integrated unit.

- Simply rebuilding by the same owner is insufficient. The critical factor is the restoration of the mortgagee's comprehensive security interest.

- Later Supreme Court cases have further refined this exception, indicating, for example, that if the new mortgage taken on the rebuilt building is junior to other pre-existing liens (like tax liens), or if it's not of the same priority rank as the original land mortgage, the "special circumstances" are not met, and no statutory superficies will arise (e.g., Supreme Court, June 5, 1997, Minshū Vol. 51, No. 5, p. 2116; Supreme Court, July 3, 1998, Hanrei Jihō No. 1652, p. 68).

Debate and Criticisms

While this 1997 judgment brought clarity to a complex issue, it has also faced some criticism:

- Theoretical Underpinnings: Some scholars have questioned whether the "reasonable intentions of the parties" provides a sufficiently robust theoretical foundation for the rule, arguing it might be more of a post-hoc justification for a desired outcome. However, legal commentary also suggests that focusing on the mortgagee's legitimate expectation of not suffering an unforeseen diminution of their security interest (which would occur if a new, unmortgaged building automatically gained a land use right that devalued the land collateral) is a defensible rationale.

- Harshness in Certain Scenarios: The rule established by this judgment has been described as potentially harsh, particularly in situations where the original jointly mortgaged building might have been destroyed due to a natural disaster (rather than deliberate demolition). In such cases, the need to encourage and facilitate reconstruction, which often requires new financing, and to protect the continued habitation or use of the property, might argue for a more lenient approach to statutory superficies for the rebuilt structure. Critics suggest that the judgment may have been heavily influenced by the need to address potentially abusive practices seen during the collapse of Japan's "bubble economy," where mortgagors might have strategically demolished and rebuilt structures to impair mortgagees' rights.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of February 14, 1997, established a clear and rather strict general rule in Japanese mortgage law: when a building that was part of an initial joint mortgage with the land is demolished, and a new building is subsequently constructed on that land, a statutory superficies will generally not arise for this new building if the land mortgage is later foreclosed. The Court prioritized the land mortgagee's reasonable expectation of holding security over the land as unencumbered bare land once the original mortgaged building (for which they had accepted a potential statutory superficies) ceased to exist. A statutory superficies for a rebuilt structure will only be recognized under very limited "special circumstances," primarily requiring the land mortgagee to be granted a new, equivalent joint mortgage over the new building, thereby restoring their original comprehensive security position. This decision has significant implications for property development, financing, and the assessment of collateral value in situations involving the reconstruction of buildings on mortgaged land.