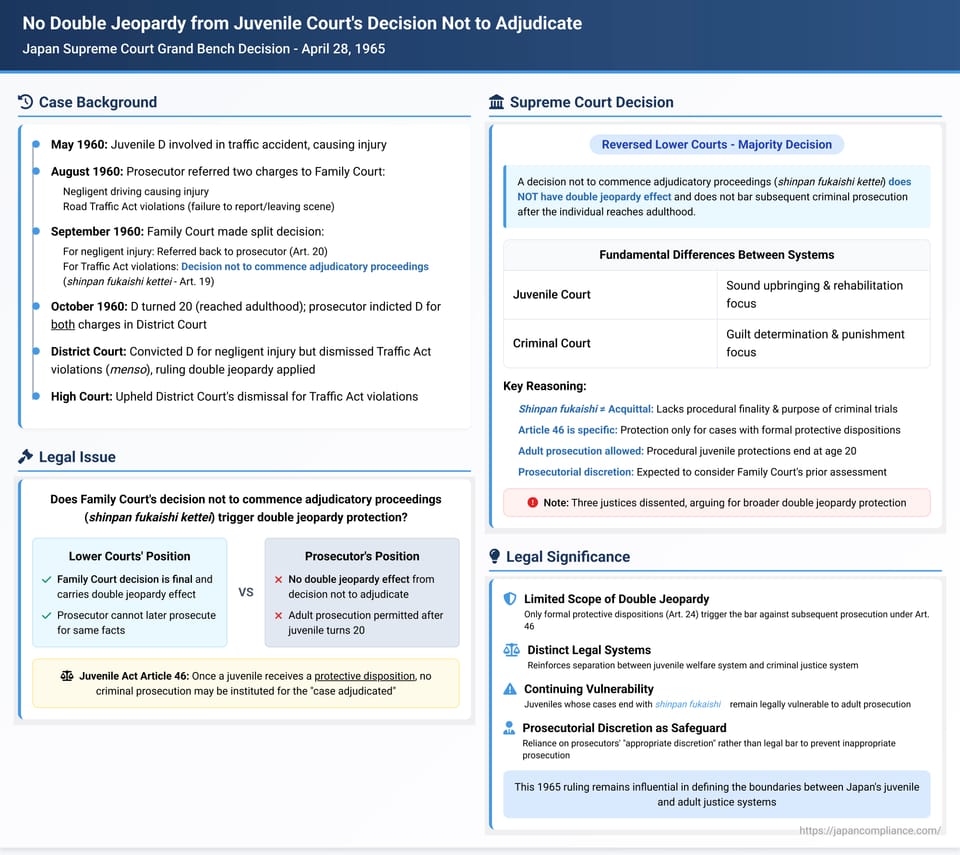

No Double Jeopardy from Juvenile Court's Decision Not to Adjudicate: Japan Supreme Court's 1965 Ruling

The constitutional protection against double jeopardy (Article 39 of the Constitution of Japan) prevents an individual from being tried or punished twice for the same criminal offense. Japan's Juvenile Act, designed for the rehabilitation and sound upbringing of minors, also contains a specific provision (Article 46) that bars criminal prosecution for a "case adjudicated" (shinpan o heta jiken) if the Family Court has already issued a protective disposition (like commitment to a training school or probation) for that delinquent act.

But the Family Court process has outcomes other than formal protective dispositions. After investigating a case referred by police or prosecutors, the Family Court might decide not to proceed to a full adjudicatory hearing (shinpan). This "decision not to commence adjudicatory proceedings" (shinpan fukaishi kettei), authorized under Juvenile Act Article 19(1), can be made for various reasons – perhaps the alleged act doesn't constitute a crime, the evidence is insufficient, the matter is trivial, or the court deems formal proceedings unnecessary for the child's welfare, perhaps after informal guidance or casework.

Does such a shinpan fukaishi decision carry the same legal finality as a protective disposition under Article 46, or as an acquittal in a criminal trial? Specifically, does it trigger the double jeopardy bar, preventing the state from later prosecuting the individual for the same underlying conduct, especially if they subsequently reach the age of majority? This fundamental question about the legal effect of a Family Court's decision not to proceed to a formal hearing was addressed by the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan in a landmark decision on April 28, 1965.

Case History: Traffic Offense, Family Court Dismissal, Adult Prosecution

The case involved defendant D, who, while still a juvenile in May 1960, was involved in a traffic accident while operating a three-wheeled vehicle for work. The incident resulted in two alleged offenses:

- Negligent Driving Causing Injury: D allegedly backed up negligently, injuring a victim.

- Road Traffic Control Act Violations: D allegedly failed to report the accident to police and left the scene without authorization, violating provisions of the then-applicable Road Traffic Control Act.

The prosecutor referred both matters to the Asahikawa Family Court in August 1960, recommending criminal disposition. In September 1960, the Family Court made two distinct decisions:

- For the negligent injury, the court referred the case back to the prosecutor under Juvenile Act Article 20, deeming criminal prosecution appropriate.

- For the Road Traffic Control Act violations (failure to report/remain), the court issued a decision not to commence adjudicatory proceedings (shinpan fukaishi kettei) under Article 19(1). The court reasoned partly on substantive grounds: it questioned the constitutionality of the mandatory reporting requirement (citing potential conflict with the privilege against self-incrimination, Constitution Art. 38(1)) and deemed the remaining violation (leaving the scene) minor.

Subsequently, on October 10, 1960, D turned 20, reaching the age of majority under the law at that time. Eight days later, on October 18, the prosecutor indicted D in the Asahikawa District Court (the adult criminal court) for both the negligent injury and the Road Traffic Control Act violations, explicitly disagreeing with the Family Court's constitutional assessment regarding the reporting duty.

The District Court proceeded to convict D for the negligent injury. However, for the Road Traffic Control Act violations, it issued a judgment of menso – a form of procedural dismissal based on prior adjudication or immunity. The District Court reasoned that the Family Court's earlier shinpan fukaishi decision on these same facts constituted a final judgment carrying the force of ichiji-fusairi (double jeopardy), barring any further prosecution. The prosecutor appealed, but the High Court upheld the District Court's reasoning and the menso dismissal for the traffic violations. The prosecutor then appealed to the Supreme Court's Grand Bench.

The Legal Question: Does Shinpan Fukaishi Confer Double Jeopardy Protection?

The central issue before the Supreme Court was the legal effect of the Family Court's Article 19(1) decision not to commence a formal hearing. Did this decision, particularly when based on substantive grounds related to the alleged offense itself, equate to an acquittal or other final judgment that would trigger the double jeopardy protections of Constitution Article 39 or the specific bar in Juvenile Act Article 46?

The Supreme Court's Decision (Majority View): No Double Jeopardy Effect

The Grand Bench, in a majority decision, ruled that the shinpan fukaishi decision does not have double jeopardy effect and does not bar subsequent criminal prosecution after the individual reaches adulthood.

Fundamental Differences Between Juvenile and Criminal Proceedings:

The Court emphasized the distinct purposes and procedures of the two systems:

- Purpose: Family Court proceedings aim at the juvenile's sound upbringing and rehabilitation (Juvenile Act goals), whereas criminal trials aim to determine guilt and impose punishment based on criminal law principles.

- Procedure: Family Court proceedings lack the adversarial structure, public trial guarantees, and strict rules of evidence characteristic of criminal trials. Factual and legal determinations in Family Court are made within the context of its protective and educational mandate.

Shinpan Fukaishi Not Equivalent to Acquittal:

Based on these differences, the Court held that a shinpan fukaishi decision, even if grounded in a finding that the alleged act was not criminal or lacked sufficient basis, cannot be equated with a criminal acquittal (muzai). It lacks the procedural finality and the specific purpose of determining criminal culpability that underlies an acquittal. Therefore, it does not generate res judicata (kihanketsu-ryoku) in the criminal context, nor does it constitute an "act of which he has been acquitted" under Constitution Article 39. The fact that there was no mechanism to appeal a shinpan fukaishi decision at the time did not imbue it with such finality.

Juvenile Act Article 46 is Specific and Limited:

The Court interpreted Article 46 – which explicitly bars prosecution after a protective disposition – as a special provision enacted due to the specific nature of protective dispositions under Article 24(1). These dispositions (like training school committal) can involve significant liberty restrictions, similar in effect to criminal punishment, and are based on findings related to specific criminal acts identified in the disposition document. Article 46 addresses this specific situation and cannot be interpreted as establishing a general rule that all final dispositions by the Family Court carry double jeopardy effect. It provides no legal basis for extending such effect to shinpan fukaishi decisions.

Adult Prosecution Permissible Post-Majority:

The Court clarified that while a juvenile generally cannot be criminally prosecuted unless the Family Court refers the case back to the prosecutor (Juvenile Act Art. 20), this procedural requirement, rooted in the Juvenile Act, ceases to apply once the individual reaches the age of majority. After that point, the prosecutor is legally free to initiate criminal proceedings for acts committed during the individual's minority, subject only to general prosecutorial discretion. The prior shinpan fukaishi decision does not legally bar this. However, the Court added a crucial caveat: prosecutors are expected to exercise their discretion appropriately, giving due consideration to the Family Court's prior assessment of the case, particularly regarding the juvenile's need for protection.

Conclusion:

The Supreme Court concluded that the shinpan fukaishi decision by the Asahikawa Family Court did not constitute a final judgment equivalent to an acquittal and lacked any legal basis for double jeopardy effect under either the Constitution or the Juvenile Act. Therefore, the lower courts had erred in law by dismissing the Road Traffic Control Act charges based on this decision. The judgment was reversed, and the case was remanded to the District Court for trial on those charges.

Dissenting Views and Lasting Impact

This decision was not unanimous; three Justices issued strong dissenting opinions. They argued, essentially, that a shinpan fukaishi decision, especially when based on a substantive investigation by the specialized Family Court, represents a conclusive determination by a state judicial body not to pursue the matter further against the juvenile. They believed this decision should be accorded finality to protect legal stability and the juvenile's prospect for rehabilitation – constantly facing the threat of later prosecution would undermine the Juvenile Act's goals. They also argued for a broader interpretation of constitutional double jeopardy, suggesting that simply being subjected to the Family Court process puts the juvenile in "jeopardy," barring subsequent proceedings for the same conduct.

Despite the dissent, the majority opinion became settled law in Japan. It established the principle that only formal protective dispositions under Juvenile Act Article 24(1) carry the specific double jeopardy effect outlined in Article 46. Other final actions by the Family Court, such as a decision not to commence a hearing (shinpan fukaishi) or even a decision of "no disposition" (fushobun) after a hearing, do not legally bar subsequent criminal prosecution once the individual is an adult (although specific exceptions now exist for cases involving prosecutor participation, introduced by later reforms).

The practical implication is significant: individuals whose cases were closed via shinpan fukaishi as juveniles remain legally vulnerable to adult prosecution for the same conduct later on. The primary safeguard against potentially inappropriate prosecutions in such cases rests not on a legal bar, but on the expected "appropriate and reasonable discretion" of the prosecutor, who is urged (but not legally required) to consider the Family Court's prior handling of the matter. This ruling continues to highlight the complex interface and sometimes conflicting goals between Japan's distinct juvenile and adult justice systems.