No Copyright, No Tort? Japan's Supreme Court on Using Works from Unrecognized States (North Korean Film Case)

Judgment Date: December 8, 2011

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Case Numbers: Heisei 21 (Ju) No. 602 & No. 603 (Claim for Injunction Against Copyright Infringement, etc.)

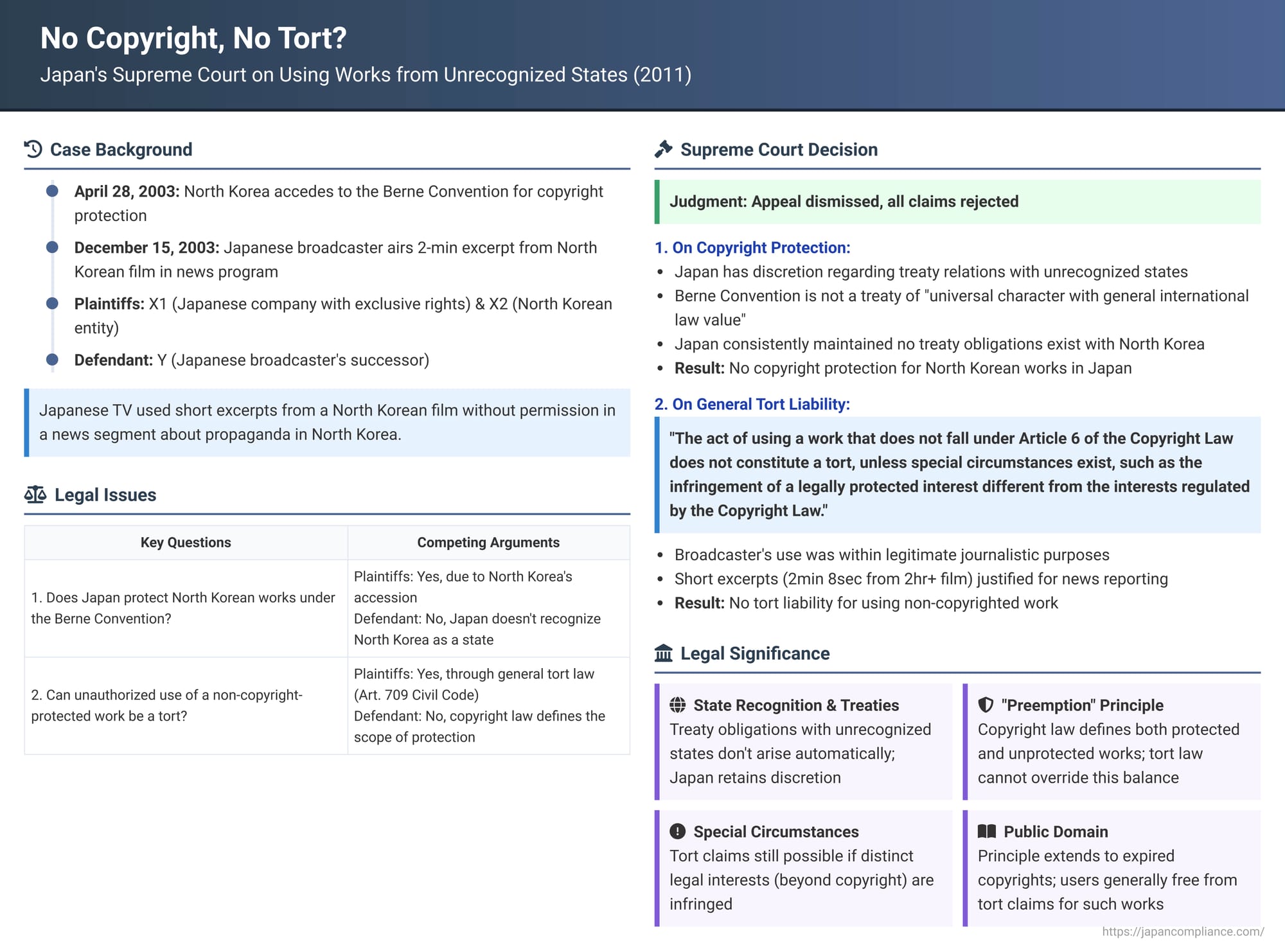

The "North Korean Film Case" (北朝鮮映画事件 - Kita Chōsen Eiga Jiken), decided by the Japanese Supreme Court in 2011, delves into complex issues at the intersection of international law, copyright protection, and general tort liability. The judgment is notable for two key findings: first, its stance on whether works originating from an unrecognized state (North Korea) are eligible for copyright protection in Japan under the Berne Convention; and second, its broader articulation of the principle that if a creative work is not protected by Japan's Copyright Law, its unauthorized use generally cannot form the basis of a tort claim under the Civil Code, unless distinct, non-copyright legal interests are infringed.

The Film, The Broadcast, and The Dispute

The case revolved around a feature film produced in North Korea and its subsequent broadcast in Japan.

- The Plaintiffs: The plaintiffs were Company X1, a Japanese corporation, and Entity X2, described as an administrative agency under the North Korean Ministry of Culture, which was recognized as having legal capacity under North Korean civil law. Company X1 had entered into a "basic film copyright agreement" with Entity X2, under which X1 obtained exclusive rights for the theatrical exhibition, broadcasting, and other exploitation of certain North Korean films within Japan. One of these films was a dramatic feature film over two hours in length ("the Film").

- The Defendant's Broadcast: Broadcaster A (whose liabilities were later succeeded by Broadcaster Y, the appellee before the Supreme Court) was a Japanese television broadcasting company. On December 15, 2003, Broadcaster A aired an approximately 6-minute segment within its "Super News" television program. This segment was intended to report on the use of films for brainwashing or indoctrination purposes targeting the populace in North Korea. In this news report, Broadcaster A included excerpts from the Film, totaling 2 minutes and 8 seconds. This broadcast was made without the permission of either Company X1 or Entity X2.

- International Treaty Context: A relevant international factor was North Korea's accession to the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works. The Berne Convention, a cornerstone of international copyright law, generally requires member states to grant copyright protection to works authored by nationals of other member states (Article 3(1)(a)). North Korea acceded to the Berne Convention, and the treaty officially came into force for North Korea on April 28, 2003, before the broadcast in question. Japan is a long-standing member of the Berne Convention.

- Japan's Stance on North Korea: However, at the time of the lawsuit and judgment, Japan had not formally recognized North Korea as a sovereign state. Consistent with this political stance, the Japanese government's position was that it was not obligated under the Berne Convention to protect copyrighted works originating from North Korean nationals or entities.

- Legal Claims: Company X1 and Entity X2 sued Broadcaster Y (as successor to A), alleging primarily:

- Copyright Infringement: They claimed that the Film was a work protected by copyright in Japan under Article 6, Item 3 of Japan's Copyright Law (which protects works that Japan is obligated to protect under international treaties, such as the Berne Convention). They asserted that the broadcast infringed Entity X2's right of public transmission and X1's exclusive licensing rights, seeking an injunction and damages.

- General Tort (Preliminary Claim): In the appellate stage, X1 added a preliminary claim arguing that even if the Film was not protected by copyright, its unauthorized use by Y constituted a general tort under Article 709 of the Japanese Civil Code, infringing X1's legally protected interests.

Lower Court Rulings:

- First Instance (Tokyo District Court): The District Court dismissed the copyright infringement claim. It held that because Japan did not recognize North Korea as a state, no treaty-based rights and obligations under the Berne Convention existed between the two. Therefore, the Film did not qualify as a work that Japan was obligated to protect under Copyright Law Article 6(iii).

- Second Instance (Intellectual Property High Court): The IP High Court largely upheld the denial of copyright protection for the same reasons. However, it partially accepted Company X1's preliminary tort claim, finding that Y's broadcast did unlawfully infringe X1's interests, and awarded a nominal amount of damages to X1.

Both sides (X1, X2, and Y) sought and were granted leave to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: No Copyright, and Generally No Tort

The Supreme Court ultimately ruled against the plaintiffs on all counts, overturning the IP High Court's finding of tort liability for Company X1 and dismissing all of X1's and X2's claims.

I. On Copyright Protection under the Berne Convention and Copyright Law Article 6(iii):

The Supreme Court addressed whether the Film was entitled to copyright protection in Japan.

- General Principle Regarding Multilateral Treaties and Unrecognized States: The Court laid down a general principle: When a state that Japan has not formally recognized subsequently accedes to a multilateral treaty to which Japan is already a party, treaty-based rights and obligations do not automatically arise between Japan and that unrecognized state. Japan retains the discretion to choose whether or not to establish such treaty relations with the acceding unrecognized state. The Court noted an exception: if the obligations imposed by the treaty are of a "universal character possessing general international law value" (普遍的価値を有する一般国際法上の義務 - fuhenteki kachi o yūsuru ippan kokusaihō-jō no gimu), then such obligations might arise regardless of recognition.

- Nature of the Berne Convention: The Supreme Court then analyzed the Berne Convention itself. It concluded that the Berne Convention primarily aims to protect works authored by nationals of its member countries (Union countries) and does not, for instance, generally protect works of authors from non-Union countries unless specific conditions (like first publication in a Union country) are met. Therefore, the Court found that the Berne Convention is structured around a framework of reciprocal obligations among member states and does not impose obligations of a universal character under general international law.

- Japan's Consistent Position on North Korea and the Berne Convention: The Court observed that Japan had consistently maintained the stance that, despite North Korea's accession to the Berne Convention, no treaty-based rights and obligations had arisen between Japan and North Korea under that convention. Evidence of this included Japan's not issuing an official public notice of the Berne Convention coming into effect for North Korea (a practice followed for other acceding nations) and the stated views of the relevant government ministries (Foreign Affairs, Education/Culture) that Japan did not consider itself bound to protect North Korean works under Berne.

- Conclusion on Copyright Protection: Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court held that Japan is not obligated under Article 3(1)(a) of the Berne Convention to protect the works of North Korean nationals. Consequently, the Film did not qualify as a work protected under Article 6, Item 3 of Japan's Copyright Law. The plaintiffs' primary copyright infringement claims therefore failed.

II. On General Tort Liability (Civil Code Art. 709) for Using Works Not Protected by Copyright:

This part of the judgment has broader implications beyond the specific facts of North Korean works. The Supreme Court addressed whether the unauthorized use of a work that is not protected by Japan's Copyright Law can nevertheless constitute a general tort.

- Copyright Law Defines the Scope of Protection and Freedom: The Court began by stating that the Copyright Law establishes a comprehensive regime. It grants exclusive rights to authors for certain types of works under specific conditions, but it also aims to harmonize these exclusive rights with the "freedom of the people's cultural life" (国民の文化的生活の自由 - kokumin no bunkateki seikatsu no jiyū). To this end, the Copyright Law defines the grounds for copyright arising, its content, scope, and causes for extinction, thereby clarifying the extent and limits of exclusive rights. Article 6 of the Copyright Law, which specifies the range of works protected in Japan, is a key provision in this legislative scheme.

- No General Right to Exclusively Use Works Outside Copyright Protection: The Court reasoned that if a particular work does not fall within the categories of protected works defined by Article 6 of the Copyright Law (as was the case with the Film), then any purported right to exclusively use such a work is, by implication, not an object of legal protection under the Copyright Law itself.

- The General Rule for Tort Liability for Using Non-Copyrighted Works: Building on this, the Supreme Court laid down a critical general principle: "The act of using a work that does not fall under any of the items of Article 6 of said Act does not constitute a tort, unless special circumstances exist, such as the infringement of a legally protected interest different from the interests regulated by the Copyright Law." (著作権法6条各号所定の著作物に該当しない著作物の利用行為は、同法が規律の対象とする著作物の利用による利益とは異なる法的に保護された利益を侵害するなどの特段の事情がない限り、不法行為を構成するものではない - Chosakukenhō roku-jō kakugō shotei no chosakubutsu ni gaitō shinai chosakubutsu no riyō kōi wa, dōhō ga kiritsu no taishō to suru chosakubutsu no riyō ni yoru rieki to wa kotonaru hōteki ni hogo sareta rieki o shingai suru nado no tokudan no jijō ga nai kagiri, fuhō kōi o kōsei suru mono de wa nai to kaisuru no ga sōtō de aru). ``

- Application to Company X1's Tort Claim:

- The Supreme Court found that the "benefit" Company X1 claimed to have been deprived of due to Broadcaster Y's actions was, in essence, "the benefit of exclusive domestic use" of the Film. This, the Court stated, is precisely the type of interest that the Copyright Law is designed to regulate and protect—if a work qualifies for copyright. Since the Film was held not to be protected by copyright in Japan, the asserted interest in its exclusive exploitation was not a legally protected interest under Japanese law. Therefore, even if this interest was harmed by Y's broadcast, such harm could not form the basis of a tort claim.

- The Court also considered an alternative interpretation of X1's claim: that Y's broadcast had harmed X1's general business interests (営業上の利益 - eigyō-jō no rieki). However, it dismissed this as well. It found that Y's broadcast was part of a television news program aiming to report on the state of affairs in North Korea, including the use of films for public indoctrination. The broadcast used only a very short excerpt (2 minutes and 8 seconds) from a much longer film (over 2 hours) and did so within a scope that was justifiable for the stated journalistic purpose. Under these circumstances, the Court concluded that Y's broadcast did not deviate from the scope of free competition and could not be said to unlawfully infringe upon X1's business interests. There was no basis for finding a tort on these grounds either.

- (Entity X2's tort claim was also implicitly dismissed on similar grounds, as its primary claim was for loss of copyright-like exclusive use benefits).

Significance and Broader Implications of the Ruling

The North Korean Film case is a significant judgment with implications reaching beyond the specific issue of works from unrecognized states.

- Copyright Protection and State Recognition: The decision clarified Japan's stance on copyright obligations under multilateral treaties with respect to states it does not formally recognize. It established that mere accession by an unrecognized state does not automatically create treaty relations with Japan unless the treaty embodies universally binding principles of general international law, a category the Court found the Berne Convention (in its relevant aspects) did not fall into. Japan retains the discretion to decide whether to enter into such treaty relations.

- The Relationship Between Copyright Law and General Tort Law – The "Preemption" Principle: This is arguably the most far-reaching aspect of the judgment. The Supreme Court essentially articulated a principle that where a specific intellectual property statute like the Copyright Law defines the scope of protection for certain types of creations (and by implication, what is not protected or is in the public domain), general tort law cannot be used as a substitute to grant equivalent exclusive rights for those same creations if they fall outside the statutory protection.

- The PDF commentary `` explains this by stating that Copyright Law, in defining what is protected, also implicitly defines what is part of the "public domain" (or in this case, outside the scope of Japanese protection) and thus generally free for use. Allowing tort law to restrict such uses based on interests that are substantively copyright-like would undermine the balance struck by the Copyright Law between protecting creators and ensuring public access and freedom to use cultural materials.

- This can be seen as a form of "preemption," where the specific legislative scheme of copyright (with its defined subject matter, scope of rights, limitations, and duration) takes precedence over the more general principles of tort law when the harm alleged is essentially the loss of exclusivity over the creative work itself.

- The "Special Circumstances" Caveat: The crucial exception noted by the Court – "unless special circumstances exist, such as the infringement of a legally protected interest different from the interests regulated by the Copyright Law" – is vital. This means the ruling does not completely bar tort claims related to the use of non-copyrighted material. If the use of such material also infringes other distinct legal rights (e.g., causes defamation, invades privacy, constitutes a recognized form of unfair competition that is not dependent on copyright per se, or infringes other personality rights), then a tort claim might still be viable. The Supreme Court itself briefly considered and dismissed the possibility of harm to X1's general business interests as a separate tort, finding the broadcaster's actions to be within legitimate journalistic bounds.

- Implications for Public Domain Works: The principles enunciated in this case would logically extend to works that were once copyrighted but whose term of protection has expired and have thus fallen into the public domain. The use of such public domain works generally cannot be restricted by asserting a tort based on the loss of exclusive exploitation rights that have ceased to exist under copyright law.

- Contextualizing with "Publicity Rights": The PDF commentary draws an analogy to the debate over publicity rights ``. If a specific IP law (like Copyright or Trademark Law) does not explicitly provide for a "right of publicity," it doesn't automatically mean that acts harming publicity interests can never be a tort. The key question, following the logic of the North Korean Film case, would be whether the "publicity interest" being asserted is substantively the same as an interest that the existing IP laws aim to regulate (and perhaps have chosen not to protect broadly or in that specific instance) or if it's a distinct legally protected interest.

Conclusion

The North Korean Film Supreme Court case delivered important clarifications on two distinct legal fronts. Firstly, it affirmed Japan's position that copyright obligations under the Berne Convention do not automatically extend to works from states that Japan does not formally recognize, unless specific universal legal principles are involved. Secondly, and with broader implications, the judgment articulated a significant principle regarding the relationship between specific intellectual property statutes and general tort law. It established that where the Copyright Law defines the boundaries of protection for creative works (including which works are not protected in Japan), general tort law cannot typically be invoked to recreate or extend copyright-like exclusive exploitation rights for those unprotected works. This reinforces the idea that the detailed legislative schemes of intellectual property law are intended to be comprehensive in defining the balance between exclusive rights and public freedoms, with general tort law playing a role primarily when distinct, non-IP legal interests are infringed. The "special circumstances" exception, however, leaves the door open for tort claims where the use of even non-copyrighted material violates other legally recognized rights.